7 Mar 2019

Colic: practical advice on diagnosing and treating gastrointestinal disorders

A common cause of death, colic is the clinical presentation of abdominal pain – and more than 100 disorders can result in the syndrome. Tim Mair offers practical guidance.

Figure 3. Congested oral mucous membranes due to hyovolaemia/endotoxaemia.

Colic is one of the most common emergency conditions encountered in equine clinical practice (Figure 1), and remains a frequent cause of death or reason for euthanasia.

Colic describes the clinical presentation of abdominal pain, and more than 100 different diseases can result in this syndrome. The diagnosis of the cause of colic is often challenging, although, in a minority of cases, a precise diagnosis of the underlying cause can be made relatively easily.

The 10 main categories of disease that can result in colic are:

- Idiopathic colic (mild abdominal pain with no distinguishing features).

- Tympany (excessive gas distension of the stomach or intestines).

- Non-strangulating/simple intestinal obstruction.

- Strangulating intestinal obstruction.

- Non-strangulating infarction.

- Peritonitis.

- Enteritis, enterocolitis.

- Functional gastrointestinal obstructions (for example, equine grass sickness).

- Gastric and colonic ulceration.

- Pain from another organ system (for example, musculoskeletal, pulmonary, urogenital; so-called “false colics”).

Attempts should be made to place every case of colic into one of these categories, since the treatment and prognosis varies considerably between them.

In general, horses with idiopathic colic and simple tympany have a good prognosis, and usually recover with simple medical or conservative treatment (for example, analgesics and temporarily withholding food or exercise).

Horses with non-strangulating/simple intestinal obstruction may or may not require surgery (for example, horses with pelvic flexure/colonic impaction usually resolve with medical therapy, but those with ileal/small intestinal impaction may require surgery), whereas horses with strangulating intestinal obstructions and non-strangulating infarction invariably require surgery, and carry a guarded prognosis for recovery.

Horses with peritonitis, enteritis and enterocolitis usually require intensive medical therapy (including antimicrobials, anti-inflammatories and IV fluid therapy), and also carry a guarded prognosis for recovery.

Horses with gastric and colonic ulceration usually improve with medical treatments. Equine grass sickness is invariably fatal, apart from those with very mild/chronic forms of the disease.

Assessment of pain

The horse affected by colic due to gastrointestinal pain may behave in different ways. To a large extent, the signs will be determined by the severity of the pain, but wide variation can be seen, dependent on the personality of the individual horse. Some horses appear to be more stoical and tolerant of pain than others.

It should be possible to classify the degree of pain exhibited by the horse into one of several groups:

- no pain

- mild pain

- moderate pain

- severe pain

- depression

The stage of depression may be seen after a severe bout of colic, as advanced intestinal necrosis and endotoxaemia produce a state of indolence. Alternatively, depression may be seen as an early sign of other diseases that produce colic, especially inflammatory diseases such as colitis and peritonitis. In general terms, the greater the severity of pain, the more severe the disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of the underlying cause of colic often requires an extensive and careful clinical examination, coupled with laboratory evaluations and diagnostic imaging. However, in many cases – especially those with “idiopathic colic” – the exact cause of the abdominal pain will never be conclusively identified.

The precise nature of the diagnostic work-up of the colicky horse will vary depending on the unique circumstances of the case. For example, a horse showing mild colic signs with no evidence of cardiovascular compromise and an unremarkable routine physical examination may simply require treatment with an analgesic drug.

However, a horse showing more severe signs of colic, or colic that recurs following analgesic therapy – with or without cardiovascular compromise – may require a more detailed examination that includes the likes of rectal palpation, abdominocentesis or abdominal ultrasonography. The horse that presents with colic signs in addition to diarrhoea (for example, colitis) is likely to require laboratory evaluations, in addition to other ancillary diagnostic procedures.

The stages of the diagnostic work up of horses with colic may involve some or all of the following procedures. In general, the more severe the signs of colic and the sicker the horse, the more of these diagnostic procedures will be required.

History and signalment

A history of previous episodes of colic or previous colic surgery should be noted, as should the history of parasite control. Colic can affect horses of any age, but some types of colic appear to be more prevalent in younger animals (for example, intussusceptions and larval cyathostominosis), whereas strangulating lipomas are more common in older horses (Figure 2).

Risk of colic, risk of requiring surgical treatment for colic, and prognosis for survival appear to be higher in older horses than younger horses. The Arabian breed has been identified in multiple epidemiological studies to be associated with increased risk of idiopathic colic. Faecaliths and impactions of the small colon appear to be more prevalent in miniature horses and Shetland ponies.

Pain assessment

What is the severity of pain – continuous or intermittent? Severe pain is generally associated with surgical diseases – but not always (for example, a horse with tympanic colic may demonstrate severe pain, but not require surgery).

Attitude

Is it depressed or alert? An episode of moderate or severe pain – followed by depression – should alert the clinician to the possibility of advanced ischaemia/necrosis of intestine.

Physical condition

Assessing body condition score, abdominal distention and colic duration. Abdominal distension in adult horses is generally associated with large intestinal disease, whereas in foals it is commonly associated with small intestinal disease.

Rectal temperature

Is it hyperthermic, normal or hypothermic? Hyperthermia may occur in peritonitis, enteritis or enterocolitis.

Heart rate and pulse – quality and rate

Elevations of heart rate in horses with colic are usually the result of anxiety, pain and hypovolaemia. A persistently high or rising heart rate (more than 60 bpm) is generally associated with severe disease requiring intensive/surgical treatment.

Persistent tachycardia, which may be unassociated with pain, is usually present in equine grass sickness.

Respirations – rate and effort

The respiratory rate of a horse with colic will usually be elevated because of pain or metabolic acidosis. Abdominal distension (for example, intestinal tympany) may cause dyspnoea due to increased pressure on the diaphragm.

Mucous membranes

Assessing colour and capillary refill time. These give an indication of the state of hydration and peripheral perfusion. Pale or congested mucous membranes and/or prolonged capillary refill time indicate hypovolaemia/endotoxaemia (Figure 3). Cyanosis may be seen in advanced circulatory shock (Figure 4).

Temperature of the extremities

This is also helpful to assess peripheral perfusion. Hypovolaemia and shock commonly results in cold extremities.

Nasogastric intubation

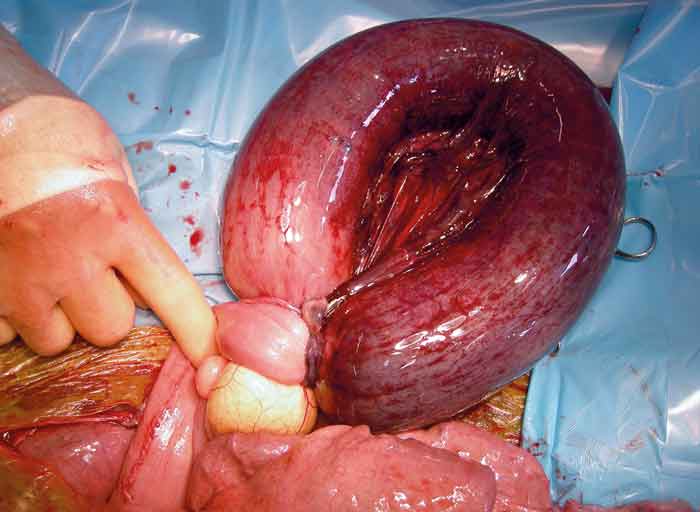

Gas, fluid reflux, colour or smell. Nasogastric intubation should be performed in horses with severe colic or with colic that either fails to improve or recurs following analgesic therapy. Horses are unable to vomit, so it is vitally important to decompress the stomach if it has become distended by sequestered fluid to prevent rupture (Figure 5).

Auscultation

Assessing borborygmi, intensity, rate (increased, decreased or absent) and tympany. This is a subjective assessment of intestinal motility usually reduced/absent in surgical colics and equine grass sickness.

Palpation of testicles and scrotum

Palpation of testicles and scrotum detects inguinal herniation.

Rectal examination

Rectal examination covers bowel distention or displacement, peritoneal surface, mesenteric pain, masses and urogenital abnormalities. It should be performed in horses with severe colic or in cases where pain recurs following analgesic therapy.

The procedure is not without risk to both the patient and the examiner, and a mental risk assessment should be undertaken prior to deciding whether it is safe to proceed with rectal examination. The small risk of iatrogenic damage to the rectum should preferably be explained to the owner prior to performing examination.

Abdominocentesis

To assess colour, whether turbid or clear, cell count and lactate concentration. These can be helpful in the diagnosis of strangulating intestinal obstructions and peritonitis.

Abdominal ultrasound

Location, motility, wall thickness and contents of the gastrointestinal tract, distended small intestine, presence of excessive peritoneal fluid, or presence of sand. With the widespread availability of portable ultrasound scanners in equine practice, and the introduction of wireless ultrasound technology (Figure 6), abdominal ultrasonography will likely become more widely used in first opinion equine practice, rather than reserved for in-clinic use.

Gastroscopy

Gastroscopy probes for squamous or pyloric ulceration.

Haematology and biochemistry

For many horses, laboratory assessment of blood is not essential. However, with severe or changing cases, white blood cell count, PCV and total plasma proteins (TPP) are often helpful.

The PCV and TPP are useful for assessing the degree of hypovolaemia, and are necessary to monitor the efficacy of volume replacement.

Treatments

A wide variety of drugs/therapeutic agents can be used in different clinical scenarios, including:

- Analgesics to control visceral pain, for example, NSAIDs (such as phenylbutazone, flunixin meglumine, ketoprofen and meloxicam), alpha2 agonist sedative drugs (xylazine, detomidine and romifidine), narcotic analgesics (butorphanol, morphine and pethidine) and spasmolytics (hyoscine).

- Agents to soften and facilitate the passage of ingesta (laxatives; oral fluids, liquid paraffin, magnesium sulphate).

- Fluids and electrolytes to improve cardiovascular function during endotoxic and hypovolaemic shock (IV fluids, enteral fluids).

- Anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce the adverse effects of endotoxin (flunixin meglumine) or intestinal inflammation (corticosteroids).

- Agents to normalise intestinal contractions during adynamic ileus (lidocaine, metoclopramide, erythromycin).

- Antimicrobial drugs (for example, for treating peritonitis).

- Anthelmintics (for example, for treating larval cyathostominosis).