24 Jun 2025

Helen Whitbread BVetMed, CertVR, MRCVS provides advice to anyone in first opinion equine practice, but especially new graduates, about facing the most common emergency in horses.

Abnormal colour mucous membranes.

This article is written as a practical guide to assist decision making around colic cases in first opinion practice and undoubtedly represents the author’s opinion.

It is backed up with science where available/appropriate1. However, if you ever do a literature search on the subject of colic, you will not be disappointed. The sheer volume of references is beyond the scope of these pages.

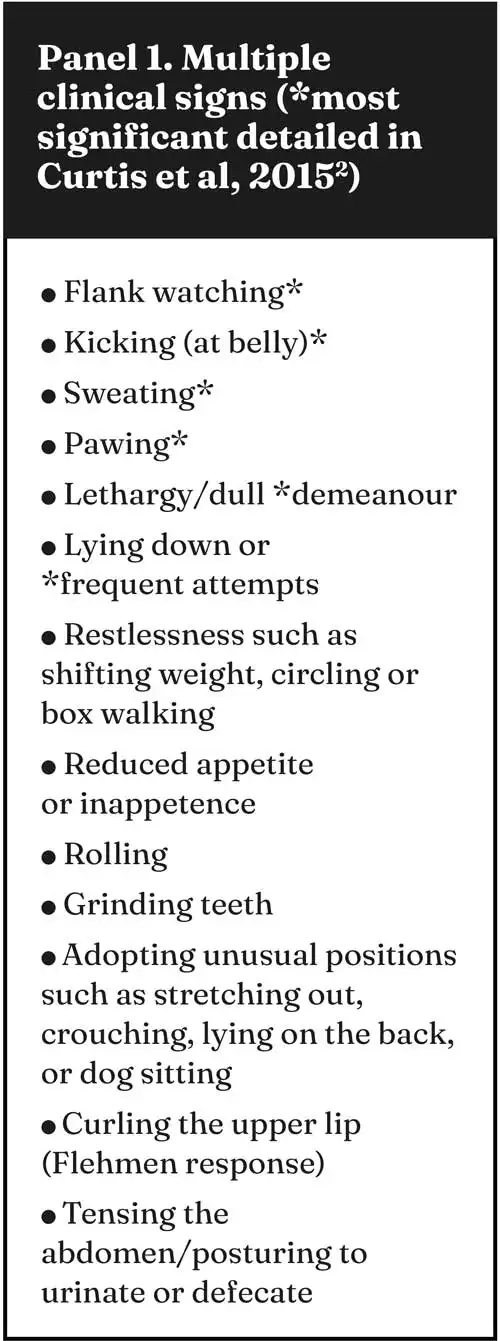

The term colic refers to clinical signs of abdominal pain (Panel 1), so should it be considered as a syndrome? It is not a single disease, simply because of the huge array of signs a case may exhibit, along with a huge list of possible underlying causes/pathologies. Colic is the most common equine emergency.

This article has been written with a bias towards the new graduate, but the author hopes it will assist all to find the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle each case presents. Although you will not have all the pieces of the puzzle every time, you should feel enabled to form a logical plan for each case. It is okay to not have all the answers. In fact, in the 2015 article by Curtis et al2, which looked at the primary evaluation of more than 1,000 cases of colic, 25.4% of the cases examined remained of unknown aetiology. Add the “gas” or spasmodic cases to this and the figure rises to 57.1% without a diagnosis.

One of the first things we learned at vet school was anatomy.

The digestive system of the average 500kg horse is 30m long. It contains three hairpin bends. The diameter of the digestive system varies between 7cm and 50cm, with some dramatic abrupt changes in diameter; for example, ileocaecal junction. The abdominal portion is partly suspended from the roof of the abdominal cavity and linked to other organs by those net curtain-like structures, the omentum and the mesentery, which (helpfully) have a few holes/gaps in them. Examples include the epiploic foramen and nephrosplenic space.

Being a hindgut fermenter is more compatible with the speed of galloping compared to a rumen, but gas production can be extensive. Combine this with the fact the mature gut can hold up to 190L of fluid, that is a huge vat of fluid and gas swinging around. So, what could possibly go wrong? (author’s emphasis).

Horse owners often panic when their horse is colicking. It is distressing to see any animal in discomfort or agony, and in reality, their concerns are well founded.

In two UK surveys1,2, 13.5% to 18% of colic cases were euthanised. So, as a new graduate, your first euthanasia may be due to a colic case.

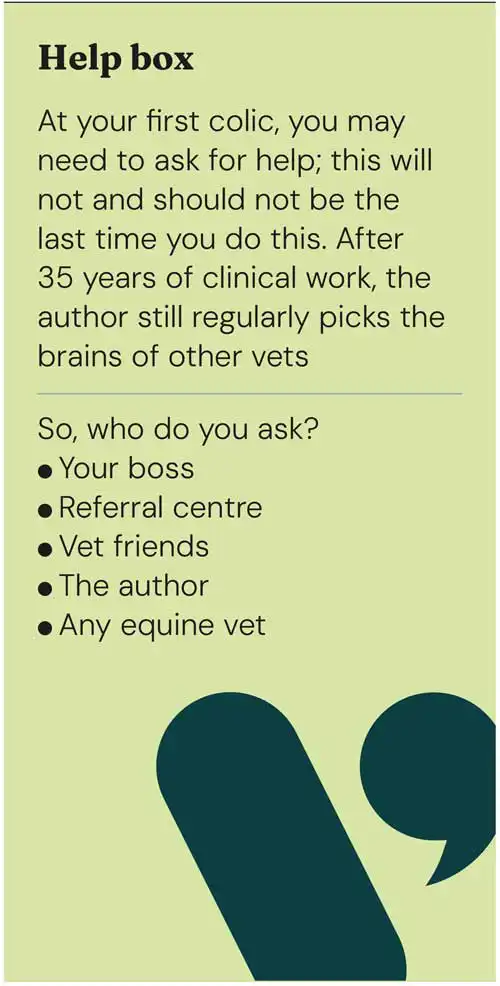

Colic is the most common equine emergency, and as a new graduate you may feel you are on your own for your first colic visit. Fortunately, obtaining your veterinary degree means you have been trained, so you will be able to gather information (clinical examination and history) to help you decide the best treatment plan. If you cannot decide, consider who you can ask for help (see Help box).

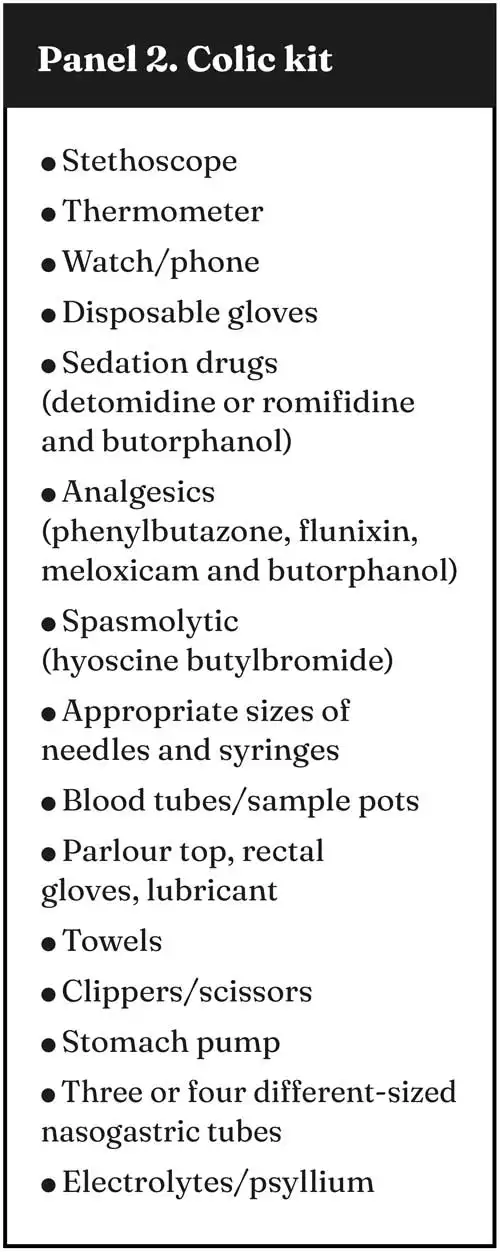

Drive safely, arrive clean and tidy, and have your car organised so you can grab your colic kit (Panel 2), introduce yourself and calmly follow your plan.

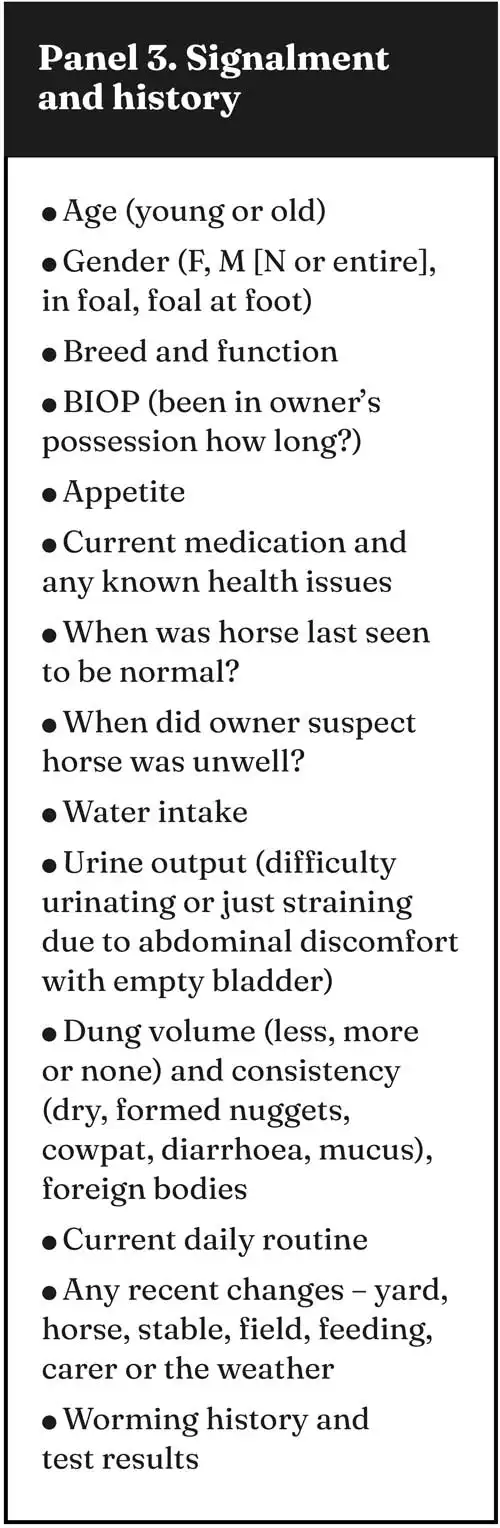

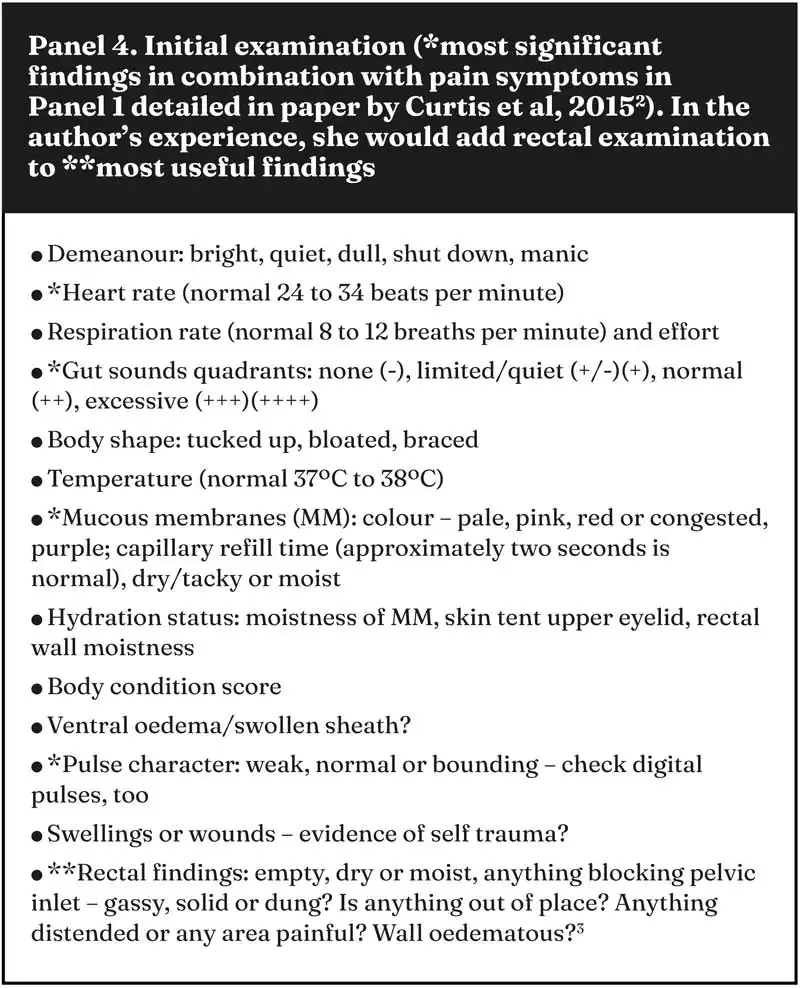

Listen to the owner give their version of events and answer your questions (Panel 3), while you carry out as thorough a clinical examination (Panel 4) as possible.

Keep it simple – is it a medical or a (potentially) surgical case of colic? If you cannot remember drug dosages, then in advance, download the BEVA drugs app and the Fédération Équestre Internationale (FEI) clean sport app. You could have a cribsheet of common drug dosages or write dosage reminders on the drug packaging. The author still carries a scribbled-on copy of Saunders Equine Formulary in her car.

If a horse is very violent or constantly going down, then sedation will be necessary for safety reasons, but also to enable a physical examination to be performed. Sedation will alter your findings, so only if safe to do so, a heart rate and assessment of gut sounds prior to sedation should be attempted. Wear a hat and suggest the owner might like to wear one, too.

Young horses sometimes have a very low pain threshold and can present very dramatically at a first colic. Ascarid burden is much more common in youngstock, while fat or veteran horses are more prone to pedunculated lipomas.

You should also keep yourself and anyone else safe, and sedate as necessary – especially to the rectal area. Temperature taking is a good guide to the behaviour you might expect when performing a rectal. Unless you have an over-the-head rectal glove, tie a knot at the top of the glove, so it sits snug around the top of your arm. Sedation and hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan; Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health) will relax the rectum. Your rectal examination may feel different to an unsedated rectal, including any painful areas, but should be safer to perform and, with plenty of lube, will reduce the risk of rectal tears.

Do not get distracted by trying to count taenial bands or identify exactly which piece of colon you are touching. Unless the gut wall is taut, you can move your hand around per rectum in the caudal abdomen and even drag things about – feeling which area has a painful, solid or gas-distended structure provides useful information, and so if no abnormalities are detected, it is all a part of solving the puzzle.

So, your initial examination may simply confirm you have a horse in pain (elevated heart rate, respiratory rate, with or without increased temperature, demeanour and behaviour). Shallow breaths may be associated with a reluctance to move the diaphragm due to abdominal pain. Gut sounds may be increased in a horse that is gassy, has diarrhoea, had new grass or has gorged itself. Reduced gut sounds may be associated with, for example, an impaction, dehydration, very distended gut walls, peritonitis, sedation or grass sickness.

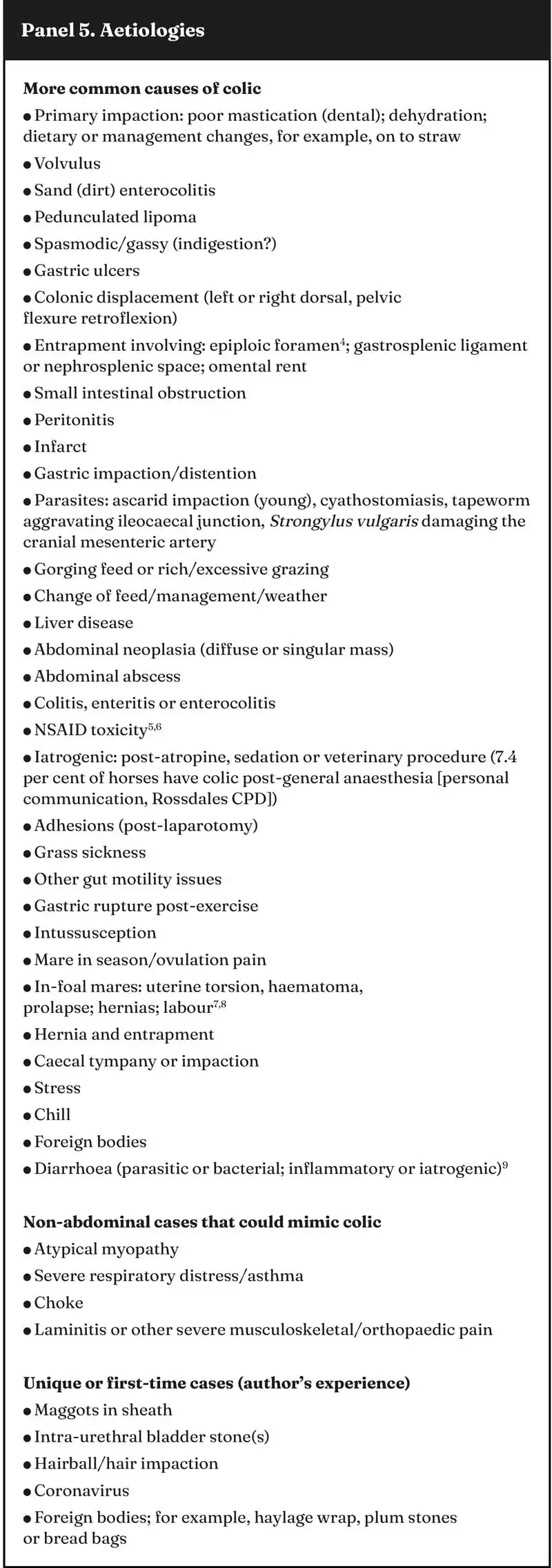

Sometimes, the degree of audible borborygmi in each quadrant (left or right, dorsal or ventral area) reflects the rectal findings. One-sided or two-sided bloating may be associated with an impaction or gas distention. A weak pulse, tacky mucous membrane or rectal dryness may be associated with dehydration. Multiple causes for colic exist, many of them listed in Panel 5, but this list is by no means exhaustive.

Remember, even if it is not your first colic, be realistic and be kind to yourself – you will not know the underlying cause for numerous colics2.

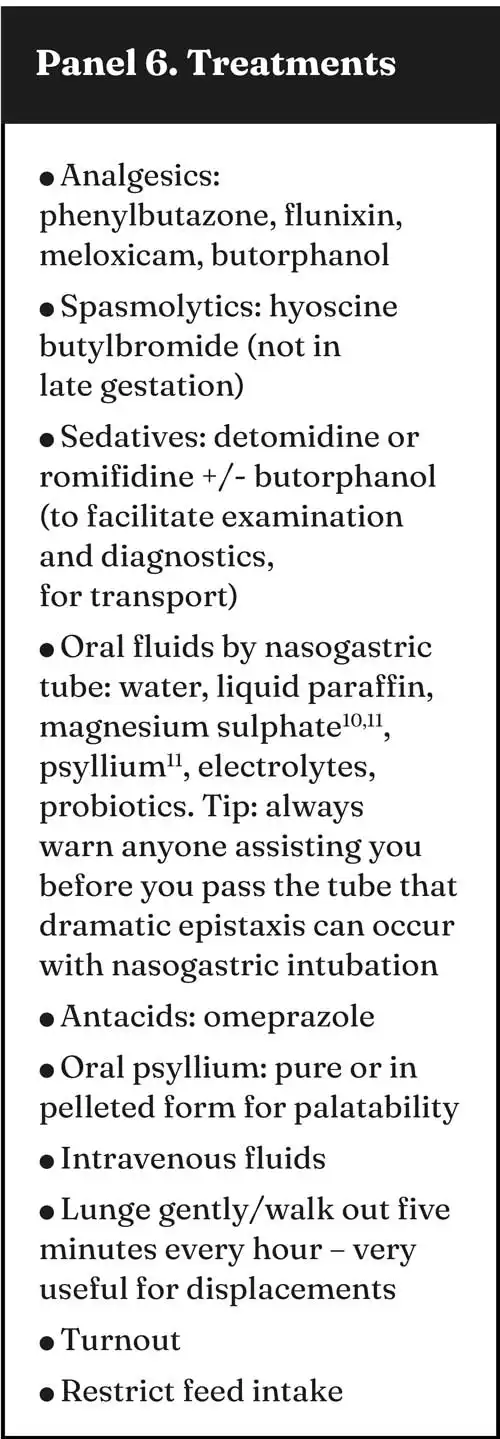

So, do not get hung up on the definitive diagnosis – as long as you have carried out a decent clinical assessment, you will be able to put together a reasonable differential diagnosis list. Keep it simple. The first job is to control the pain with analgesics. Then, make sure the horse is adequately hydrated. This means the majority of colics on initial examination will require an analgesic and fluids (Panel 6).

Remember, spasmolytics slow the gut peristalsis, which you may not want for an impaction/suspected obstruction or a horse without any gut sounds, although its effects in a normal horse probably only last for 20 to 30 minutes. Of course, you may have used it to aid a rectal examination or because the horse has excessive gut sounds; it is ideal for the horse showing a mild on/off pain response, suggestive of waves of pain or spasms.

Buscopan compositum contains a low level of the NSAID metamizole; Spasmipur (VetViva Richter) does not and can be combined with other NSAIDs. Treat any underlying cause if known and consider preventing further colic episodes. The author’s choice of analgesic is based on the degree of pain she has assessed, and if referral is an option (Panel 7).

In general terms, the author would usually give phenylbutazone as her first-line treatment and expect a simple or non-critical case to appear clinically improved within minutes. Oral fluids via a nasogastric tube can initially assist with establishing if gastric emptying could be a problem by testing for reflux. Gastric stasis, or obstruction of the stomach exit, is a concerning sign, but in its absence, the author would always treat any impaction case with oral fluids10.

For dehydrated cases or those with very limited gut sounds that are not candidates for referral, the author usually also administers oral fluids as part of treatment. So, she would always use psyllium (with or without magnesium sulfate) if she suspects sand is inducing an enterocolitis or sand impaction11.

It is always difficult to generalise about treatments, because horses appear with heart rates that have not exceeded 40, but that have needed an exploratory laparotomy, while some horses with no gut sounds (and probably near-normal heart rate) have responded instantly to just one NSAID injection and never looked back. This is why, whenever possible, you will use the other pieces of the jigsaw – a rectal examination3 or other diagnostics.

The following definitions are fairly new, but useful terminology2.

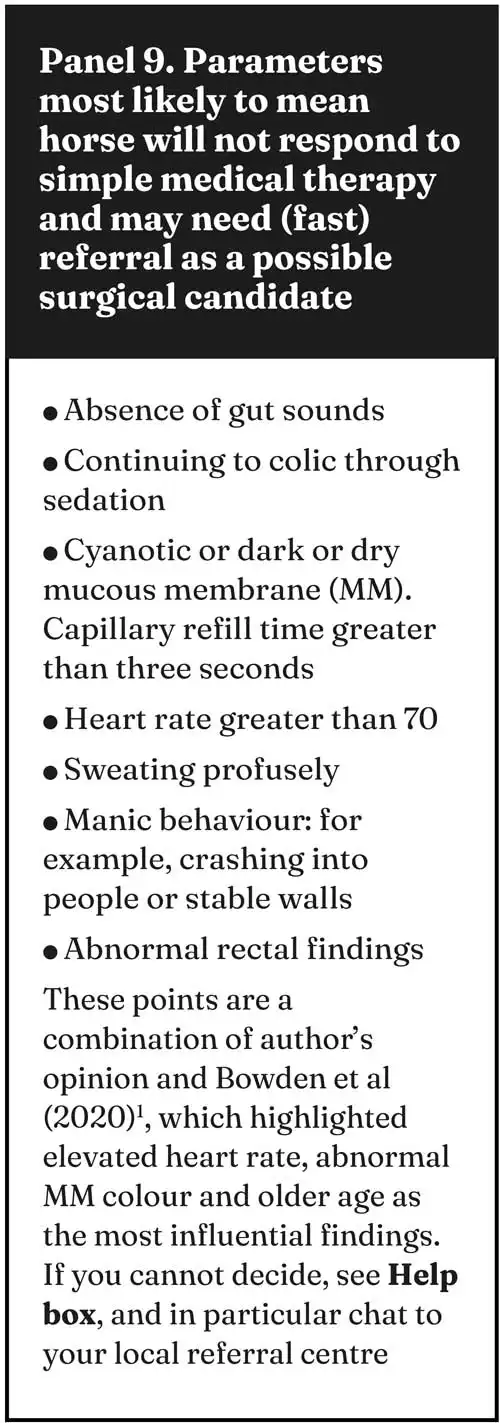

A non-critical case is considered one that has responded positively to simple medical intervention. A critical case is one that has required more extensive medical therapy, surgical intervention, euthanasia or where the animal has died.

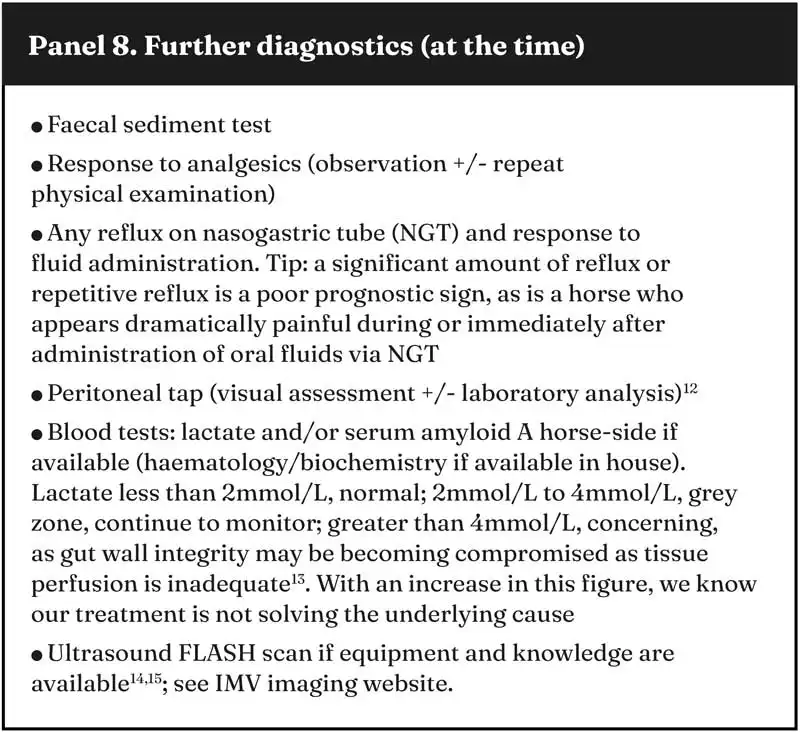

Deciding when to perform further diagnostics (Panel 8) is somewhat case dependent. If, after a standard dose of detomidine or romifidine, the horse is still in a lot of pain, in the author’s experience the horse is unlikely to respond to a simple medical treatment alone.

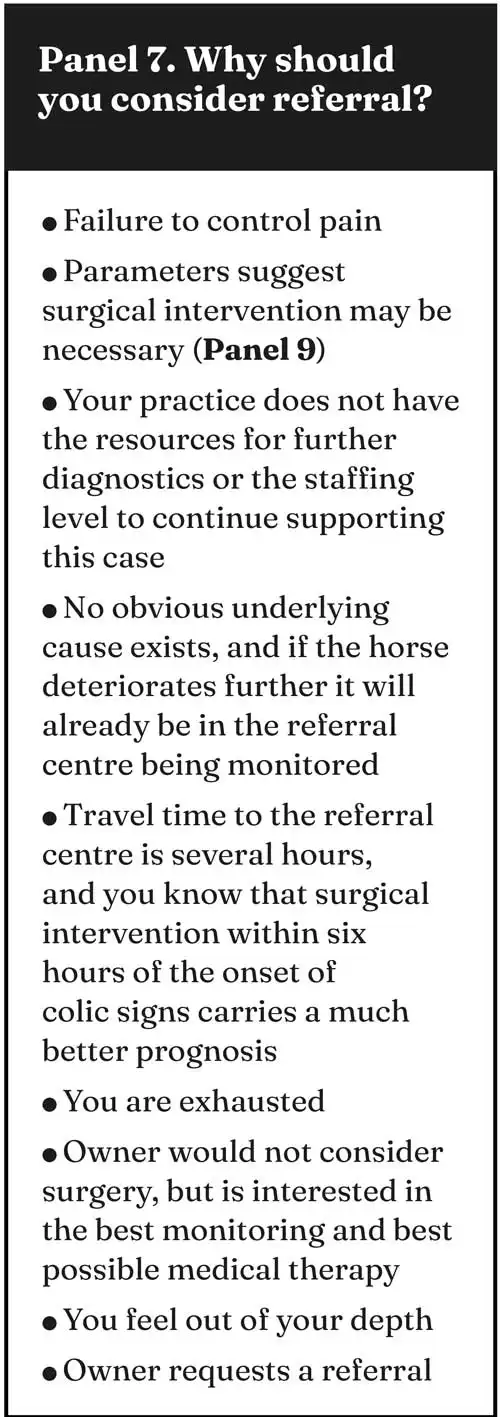

As a first opinion vet, you are important to every horse you examine and vital to their owner or keeper. Your job is firstly to provide pain relief and secondly, if possible, to prevent recurrence. However, your other priority is to gather enough facts or pieces of the jigsaw to decide whether the horse needs to be referred for further medical or surgical treatment, or euthanasia should be discussed (Panel 7).

So, for a particular horse, if you cannot achieve or maintain pain control, three options can be discussed with the owner or carer:

Continuing medical therapy. This could be at home or a referral (with or without further diagnostics).

Referring for consideration of surgery (cost, insurance, general anaesthesia risk, drugs for transport, prognosis).

Euthanasia.

If you are referring and a horse seems too painful to travel, ask the referral centre for drug/sedation dose advice.

A manic horse which suddenly goes quiet and dull may have ruptured a gastrointestinal tract structure, suddenly releasing pressure and reducing pain, but accelerating systemic toxicity.

Financial considerations, convenience, bad previous experience, comorbidities or poor performance, age of the horse or poor prognosis may all be reasons a client considers euthanasia.

Others including it being too stressful to continue treatment, concerns about the risk of general anaesthesia or transport not being an option.

At 50 years of age, the author had her first hat lightbulb moment: why only wear a hat when a situation became dangerous?

All horses are potentially dangerous, so she is one of a growing number of vets who cares more about their brain than their image or the effort it takes to put a hat on. Break a dumb habit: protect your head with a hat.

An old horse that has never colicked before always strikes fear into the author’s heart, because it seems (personal observation) a high proportion of these do not resolve with simple medical management. A few will be referred, but many will be euthanised. Although, of course, you as a vet will have done your job well and prevented suffering, it always seems so unfair for the old horse and lovely client to have such a horrible last day together.

Cribbing and wind-sucking increase colic risk and, in particular, an epiploic foramen entrapment16,4.

But the most frequently recorded risk factor is a change in feeding or management, including yard, companion, stable, field, owner/carer or the weather16.

Simple preventions include parasite control, regular sand dung testing and avoiding sudden changes in management.

As part of the diagnostic process, laparoscopy is starting to be used. Additionally, in some cases, it can offer a treatment option, negating the need for a general anaesthesia, with its associated risks and costs. Exploratory laparoscopy under standing sedation and local anaesthesia is eloquently discussed and beautifully illustrated by Pudert et al17.

Discussion of the financial implications of an exploratory laparotomy should take place before referral, and again at the referral centre. Laparoscopy may offer a cheaper alternative in some cases, but more research, and particularly long-term follow up of cases, is required before conclusions can be suggested17,18. The timing of this article is poignant, as in the same issue of the Equine Veterinary Education journal, Elane et al19 offered an insight into the impact of COVID-19 and the subsequent rising costs on the number of horses whose owners would still finance colic surgery, comparing one clinic in the US and another clinic in the UK.

Factors other than finances must also be considered, such as an ageing horse population. This article shows that in 2023, the average invoice from the one contributing UK clinic for a surgical colic recovering from the general anaesthesia was £9,000. This figure is considerably higher than the majority of UK equine vet fee insurance policies would cover in an accepted claim.

In 2019, Barker and Freeman20 assessed the costs and insurance policy details for the referral of colic cases in the UK. A considerable rise in insurance premiums and veterinary costs has been seen since this paper was published, meaning the complexity and challenges around decision making for critical colic cases will not have got any easier.

The parasite Strongylus vulgaris was a regular finding during colic surgery when the author qualified. Anthelmintic resistance and less blanket worming in the UK means this it is now re-emerging issue18.

The equine microbiome and biomarkers21,22 are two of the most interesting areas of research that may help us, the first opinion vet, in the future.

So, your first job may be in equine or mixed practice. Well done for reaching your dream – this is the start of an amazing journey in which you will succeed and help numerous horses and their owners or carers.

Ensure you surround yourself with supportive people; ours is a caring profession. Relish the cases you save and accept the compliments gracefully.

Sadly, you know you will not save them all. However, being professional and guiding everyone through a decision process, including the acceptance of euthanasia, really is you still doing your job very well, regardless of the underlying reasons.

The author declared she was ready and willing to offer additional phone advice to new graduates.