25 Nov 2019

Coughing in adult horses

Nicola Menzies-Gow discusses the diagnostic approach for this common issue, as well as differential diagnoses and appropriate further tests.

In the 2018 National Equine Health Survey, respiratory disease was the fourth most common category of disease syndrome recorded – accounting for 7% of reported veterinary problems (Blue Cross, 2018).

Severe equine asthma (formerly recurrent airway obstruction/heaves) was the second most commonly reported individual medical problem (4.9% of all syndromes) and accounted for 70% of all respiratory problems. Infectious respiratory diseases were infrequently reported (1.5%), with strangles (Streptococcus equi subspecies equi) being the most commonly reported (28% of infectious respiratory diseases).

Additionally, respiratory disease is the second most common disorder that limits performance in horses, ranked only behind musculoskeletal disease in importance. Therefore, respiratory diseases are commonly encountered by first opinion equine vets.

The clinical signs of respiratory disease are varied and can include:

- nasal discharge

- enlarged submandibular lymph nodes

- pyrexia

- coughing

- tachypnoea

- dyspnoea

- respiratory noise at rest and/or exercise

- poor performance

However, it should be remembered respiratory disease may also be subclinical.

Cough reflex

Coughing is defined as a sudden, forceful, noisy expulsion of air through the glottis to clear mucus and particles from the airways. It is a reflex that is part of the respiratory defence mechanism that, together with the mucociliary escalator, clears undesired material from the airways.

It is initiated by stimulation of irritant receptors located between the epithelial cells from the level of the larynx to the distal bronchioles, and by receptors located in the lung parenchyma and pleura.

The receptors are stimulated by mechanical deformation, chemically inert dust particles, foreign bodies, pollutant gases, exposure to hot or cold air, inflammatory conditions, excessive mucus or exudates, and chemical mediators such as histamine.

Most of the afferent impulses travel in the vagus nerve – but also in the glossopharyngeal, trigeminal and phrenic nerves – to cough centres in the medulla oblongata.

Therefore, coughing can occur in association with a wide range of infectious and non-infectious disorders, affecting the upper respiratory tract (URT) and/or lower respiratory tract (LRT).

Diagnostic approach

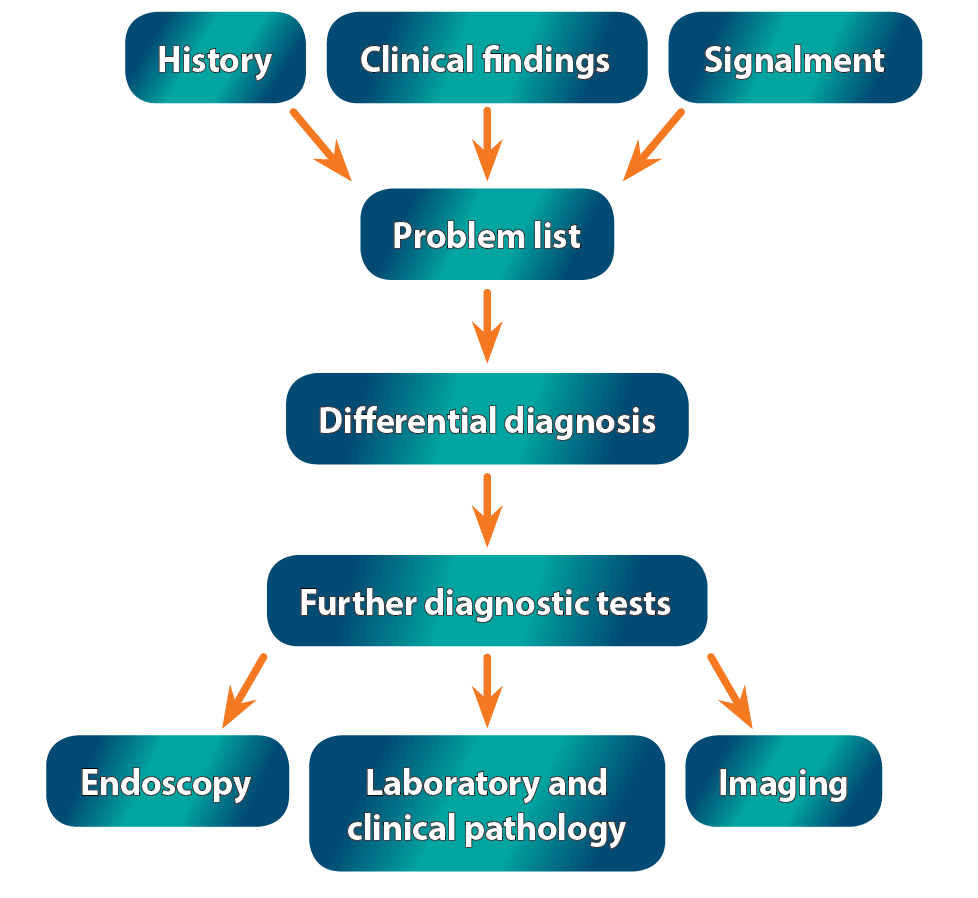

The investigation of coughing in an adult horse should start, as always, with taking a thorough history and performing a clinical examination (Figure 1).

Questions relating to the daily management of the animal – including stabling and feed, anthelmintic use and previous respiratory disease – may be of particular relevance.

Additionally, the animal’s signalment may provide useful information regarding the potential for certain disease.

Once the problem list has been formulated, it may be possible to determine whether the coughing is associated with a URT or LRT disorder, and whether the disorder is likely to be infectious.

For example, a cough caused by a URT infectious disorder may be accompanied by pyrexia, lethargy, nasal discharge and enlarged submandibular lymph nodes, whereas an LRT infectious disorder may similarly be accompanied by pyrexia and a nasal discharge, but also by tachypnoea and/or dyspnoea, and reduced performance.

However, it should be remembered not all cases fit neatly into these boxes.

Differential diagnoses

The differential diagnoses that should be considered in an individual case will vary according to whether the cough is URT or LRT in origin (or both) and whether additional clinical signs are suggestive of the cause being infectious or non-infectious.

Possible differential diagnoses are listed in Panels 1 and 2.

Infectious:

- Equine influenza virus

- Equine herpesvirus-1

- Equine herpesvirus-4

- Equine rhinitis virus

- Equine viral arteritis

- Strangles (Streptococcus equi subspecies equi)

Non-infectious:

- Subepiglottic cyst

- Epiglottic entrapment

- Arytenoid chondritis/chondrosis

- Recurrent laryngeal neuropathy

- Foreign body

- Progressive ethmoidal haematoma

- Dorsal displacement of the soft palate

Infectious:

- Common:

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Uncommon:

- Bacterial pleuropneumonia

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Pulmonary abscessation

- Interstitial pneumonia

- Lungworm

- Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis

Non-infectious:

- Common:

- Severe equine asthma (formerly recurrent airway obstruction, heaves)

- Mild to moderate equine asthma (formerly inflammatory airway disease)

- Uncommon:

- Tracheal stenosis/collapse

- Foreign body

- Left-sided heart failure

- Exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage

- Smoke or chemical irritation

- Neoplasia

Appropriate further diagnostic tests

The most appropriate further diagnostic tests will depend on whether investigation of the URT or LRT (or both) is required and the most likely differential diagnoses.

Additionally, test selection will depend on whether vets are trying to rule in or out specific diseases on the differential diagnosis list.

Vets should also consider whether the results of the test will change the therapeutic or management recommendations and whether the advantages of the test outweigh the potential disadvantages.

Tests to consider are:

Clinical pathology

Upper airway sampling

Nasopharyngeal swab: a nasopharyngeal swab is used to detect URT infectious disease caused by agents that are not normal inhabitants of the URT, using culture and/or PCR.

It is primarily used to distinguish viral causes of URT disease – for example, equine influenza virus, equine herpesvirus-1 and equine herpesvirus-4, and to detect S equi subspecies equi.

When taking nasopharyngeal swabs for strangles, it is particularly important to sample the back of the pharynx around the opening of the guttural pouch – using specially designed elongated swabs with enlarged absorbent heads – to optimise the chances of detecting the organism if it is present.

Shedding of S equi into the nasopharynx often occurs intermittently, so a series of three swabs taken one week apart is recommended to confirm negative results.

Guttural pouch lavage: a guttural lavage is obtained using endoscopy, and bilateral samples are primarily used for the detection of S equi subspecies equi carriers via culture and PCR.

Lower airway sampling

Samples from the lower respiratory tract can be obtained via three methods – namely a tracheal aspirate (TA) obtained using endoscopy, a transtracheal wash or bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). The sample can be submitted for cytology and bacteriology.

When interpreting the bacteriology results, it should be remembered samples obtained by TA and BAL can potentially be contaminated by oropharyngeal bacteria.

Thoracentesis may be appropriate in cases where an accumulation of pleural fluid is present. Percutaneous sampling of the fluid is performed, and the fluid submitted for cytology and bacteriology.

Ultrasound should be used to select the site where the largest and most ventral location of fluid accumulation is present. If fluid is present on both sides of the chest, samples should be obtained from each hemithorax – although horses have a fenestrated mediastinum, fibrin accumulation often occurs, resulting in blockage.

Blood tests

Viruses: viral causes of URT disease can be distinguished by obtaining paired samples 10 to 14 days apart and submitting for serology, and a rising antibody titre looked for.

Alternatively, blood samples can be used for isolation of the virus or detection of viral RNA by PCR if the virus enters the circulation – for example, equine herpesvirus-1 and equine viral arteritis. Haematology may reveal lymphopenia or lymphocytosis.

Bacteria: blood samples can be used to detect antibodies to S equi subspecies equi infection using an ELISA.

Newly exposed horses take at least two weeks to develop sufficient antibodies to give a positive blood ELISA result and may remain positive for up to six months after recovery.

As with all ELISA tests, false-negative (7%, based on 93% sensitivity) and false-positive (less than 1%, based on more than 99% specificity) results may occur.

Therefore, results must be interpreted carefully and in the context of the specific situation in which they are being used.

Hyperfibrinogenaemia, neutrophilia and increased serum globulin concentrations are also common in bacterial infections.

Lung biopsy

Percutaneous lung biopsy should be reserved for cases where a diagnosis has not been reached using the more common diagnostic techniques.

It is appropriate in cases where a generalised abnormality of the pulmonary parenchyma is present on radiography or ultrasonography, or where a discrete soft tissue lesion is present that is not an abscess.

Ultrasound should be used to guide sample collection, and the sample obtained submitted for histopathology and bacteriology, if appropriate.

Potential complications include coughing, epistaxis, pulmonary haemorrhage, tachypnoea, respiratory distress and pain.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy allows visual inspection of many critical structures of the URT and LRT, including the nasal passages, guttural pouches, nasopharynx, soft palate, larynx, trachea (Figure 2) and mainstem bronchi.

Horses are generally tolerant of endoscopy and, in some instances, do not require sedation, which is desirable if assessment of laryngeal function is required.

Diagnostic sampling can be undertaken as part of the endoscopic examination – for example, tracheal aspirate, BAL, guttural pouch lavage and soft tissue mass biopsy.

Although many abnormalities of the URT can be identified at rest, some conditions require the use of dynamic endoscopy while under saddle or on a high-speed treadmill.

Imaging

Radiography: although conventional radiographs of the head may provide some insight into disease origin, additional imaging modalities – such as CT or MRI – are often required to fully assess URT structures such as the larynx, nasopharynx and guttural pouches.

Thoracic radiographs in the adult horse require four overlapping images to successfully image the entire thorax. They allow imaging of the pulmonary parenchyma, mediastinum and thoracic wall.

Thoracic radiographs are particularly useful in cases that involve structures deeper than the superficial pulmonary surface – for example, pulmonary abscesses, interstitial pneumonia (Figure 3), pneumothorax and mediastinal mass.

Ultrasonography: ultrasonography can be used to provide information about the lungs and pleural cavity.

It allows detection of pulmonary disease that extends to the periphery – for example, pulmonary consolidation, atelectasis, abscesses and masses.

However, it should be remembered aerated lung will obscure deeper lesions.

Additionally, it allows detection of either fluid (Figure 4) or air in the pleural cavity.

Reaching a diagnosis

The results from the chosen test should be interpreted in light of the individual animal and used to inform the choice of further tests or to make a definitive diagnosis.

The most appropriate therapy will depend on this diagnosis, and is likely to involve both medications and management changes to reduce inhalation of environmental respiratory allergens.

References

- Blue Cross (2018). National Equine Health Survey, http://bit.ly/2NBHe28