12 Nov 2020

Diagnosing thoracolumbosacral pain: ridden versus genuine types

Sue Dyson discusses the need for equine vets to understand training principles and equine behavioural responses to recognise the difference between causes of pain.

It is an ingrained belief in the equine industry that some horses misbehave when ridden. This is often attributed to either the horse being difficult, or the rider being incapable of riding the horse.

No doubt, the combination of an inexperienced rider, who lacks skill and, perhaps, core strength with a strong, feisty and “big-moving” horse is likely to result in a horse-rider mismatch – and the horse will be unlikely to fulfil its athletic potential.

Some horses lack trust in the rider and may try to evade their aids. Such horses may rapidly respect the aids if applied by a more skilled rider, who does not have to provide force or coercion, with resultant significant improvement in performance. However, the need to provide strength, domination and submission is not in tune with the basic principles of training1, and is likely to imply either incorrect training or underlying musculoskeletal pain.

We need to understand both training principles and equine behavioural responses to recognise the difference between the two.

A fundamental question we must ask is whether genuinely difficult or naughty horses exist. I believe a sub-set of horses has developed a single vice when ridden – for example, rearing – that may not reflect underlying discomfort. This single behaviour may be managed by a skilled rider by understanding the circumstances that provoke the behaviour. However, a ridden horse ethogram has been developed (Panel 1), which comprises 24 behaviours that are each at least 10 times more likely to be seen in a horse with musculoskeletal pain (including thoracolumbosacral pain) than in a non-lame horse, or one without musculoskeletal pain2-6.

- Repeated changes of head position (up/down).

- Head tilted or tilting repeatedly.

- Head in front of vertical (≥30°) for ≥10s.

- Head behind vertical for ≥10s.

- Head position changes regularly, tossed or twisted from side to side, corrected constantly.

- Ears rotated back behind vertical or flat (both or one only) ≥5s; repeatedly lay flat.

- Eyelids closed or half closed for 2-5s; repeated blinking.

- Sclera (white of eye) exposed.

- Intense stare for 5s.

- Mouth opening ± shutting repeatedly with separation of teeth, for ≥10s.

- Tongue exposed, protruding or hanging out and/or moving in and out.

- Bit pulled through the mouth on one side (left or right).

- Tail clamped tightly to middle or held to one side.

- Tail swishing large movements: repeatedly up and down/side-to-side/circular; during transitions.

- A rushed gait (frequency of trot steps >40/15s); irregular rhythm in trot or canter; repeated changes of speed in trot or canter.

- Gait too slow (frequency of trot steps <35/15s); passage-like trot.

- Hindlimbs do not follow tracks of forelimbs, but deviated to left or right; on three tracks in trot or canter.

- Canter repeated leg changes: repeated strike off wrong leg; change of leg in front and/or behind; disunited.

- Spontaneous changes of gait (for example, breaks from canter to trot or trot to canter).

- Stumbles or trips/catches toe repeatedly.

- Sudden change of direction, against rider direction; spooking.

- Reluctant to move forward (has to be kicked ± verbal encouragement), stops spontaneously.

- Rearing (both forelimbs off the ground).

- Bucking or kicking backwards (one or both hindlimbs).

The presence of 8 or more of the 24 behaviours is highly likely to reflect the presence of musculoskeletal pain, although some horses with musculoskeletal pain may show less than 8 behaviours. The substantial reduction in the number of behaviours exhibited after removal of underlying pain by diagnostic anaesthesia, with or without improved bit or saddle fit, validates a causal relationship between pain and the behaviours3,4.

Additional features to those in the ethogram, which may also reflect pain, include teeth grinding, sweating and/or an increased respiratory rate or noise disproportionate to the work performed, and the environmental conditions, tension and general reduced compliance to a rider’s aids – including an alteration in rein tension (lack of rein tension, excessive rein tension, asymmetrical rein tension)3,4.

The clinical signs associated with primary thoracolumbosacral pain are often rather non-specific7, and often overlap with those observed in association with lameness, for example, lumbar epaxial muscle tension and pain, and lack of hindlimb impulsion8-10. In the presence of musculoskeletal pain, a more skilled rider may make a horse superficially perform better than a non-skilled rider, and any abnormal behaviours included in the ridden horse ethogram may change – although, usually abnormal behaviours persist. An ill-fitting saddle and/or girth11-14 may also induce major behavioural changes that can be immediately improved by switching to a better-fitting saddle or girth.

A group of so-called “cold-backed horses” shows abnormal behaviour when first tacked-up or mounted, or when first moving forwards. The spectrum of behaviours ranges from extending the thoracolumbosacral region when first mounted, and taking short length steps with all four limbs, to explosive, rodeo-type bucking behaviour. Some of these horses rapidly improve and can subsequently work normally, and in many of these horses an underlying cause does not appear present. For example, some horses tense as the girth is tightened, and as soon as the horse is asked to move forwards it may flex its back and take short steps, and then explode in a series of humping bucks, with the thoracolumbar region in flexion.

This behaviour may be worse when using a girth with elastic insets compared with one without. If made to canter on the lunge, this behaviour may stop completely, and such horses may then be safe to ride. Careful management of the horse, by doing up the girth very slowly, hole by hole and then moving the horse forwards at walk (with or without trot and canter on the lunge), may be sufficient to manage the horse successfully so it is safe to ride thereafter.

However, some horses have associated hypersensitivity to light palpation in the girth region on one, or both, sides15-17. Treatment of this region results in amelioration of clinical signs. Occasionally, such behaviour is associated with gastric ulceration and resolves with treatment of the ulcers17. Recognition of ill-fitting saddles, improving saddle fit, and treatment of associated pain are crucial to successful management. In a small proportion of affected horses, it appears the horse has become frightened by a rider falling off, and has become terrified by a rider being upright in the saddle. Such horses may be reconditioned, by a skilled professional trainer, by “rebacking” the horse, and by the use of a dummy rider (Figure 1). However, some horses may never be entirely reliable.

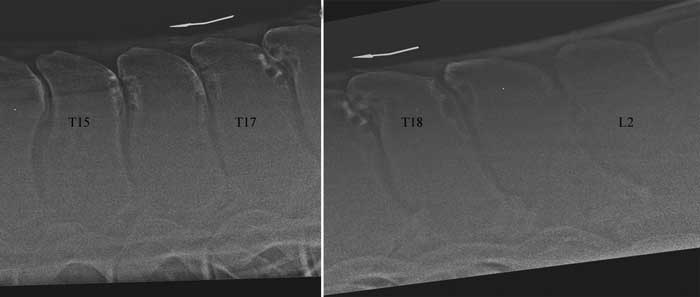

A minority of horses have extensive impinging spinous processes in the mid to caudal thoracic region (Figure 2). Clinical signs of rodeo-type bucking may be replicated by the use of a weighted roller (approximate total weight 45kg; Figure 3) and by evaluating the horse on the lunge, negating the need to ride the horse. Bucking can be abolished by infiltration of local anaesthetic solution around the impinging spinous processes if these are the underlying source of pain and behaviour. However, in many horses the presence of impinging spinous processes is not clinically significant.

Observation of the horse’s behaviour when tacked up can help to determine the presence of underlying musculoskeletal pain and/or an ill-fitting saddle with or without girth. Biting, putting the ears back, head tossing, tail swishing, fidgeting, kicking or striking out are abnormal behaviours likely to reflect pain. Some so-called “cold-backed” horses, which can be managed by careful tacking up, become tense when the girth is tightened, but they may not show these other behavioural signs.

Rider weight distribution can also significantly influence equine performance and behaviour18-20. If the seat of the saddle is too small for the rider, either due to the rider’s leg length and position in the saddle, or due to the rider’s buttock size, this results in the cantle of the saddle acting as a lever arm. Increased force transmitted through the caudal aspect of the saddle can induce equine thoracolumbar pain.

Use of an NSAID, at a high enough dose relative to the horse’s bodyweight, and used for a sufficient length of time, may help to identify horses with underlying musculoskeletal pain. In the author’s experience, phenylbutazone is the most effective drug, at a dose of 4.4mg/kg twice a day by mouth, for a minimum of five days. While clinical improvement during treatment indicates the presence of musculoskeletal pain, a negative response does not preclude musculoskeletal pain.

Clinical features to pay particular attention to include thoracolumbosacral epaxial muscle development. Poor development usually indicates the horse has not been working correctly. This could be for a number of reasons, including inappropriate training, an ill-fitting saddle, or underlying musculoskeletal pain, which could include primary thoracolumbosacral pain.

Systematic palpation should determine the alignment of the summits of the spinous processes, and the presence of abnormal epaxial muscle tension and pain. Pain may be manifest by the horse putting its ears back, threatening to bite, swishing the tail, picking up a forelimb or hindlimb, or striking forwards or kicking, or fidgeting.

Assessment of the dynamic range of motion – and the behavioural responses to gentle stimulation to flex and extend the thoracolumbosacral vertebral column in the sagittal plane, lateral bending and rotation – can be helpful. Restricted movement, exacerbation of epaxial muscle tension and demonstration of abnormal behaviours are clues to the possible presence of primary thoracolumbosacral, or sacroiliac joint region, pain. Deep, firm palpation in the cranial saddle region is important to identify deep pain, which reflects a chronically ill-fitting saddle13.

Exclusion of lameness, by assessment of the horse in hand, on the lunge and also ridden (if safe to do so), is important. However, occasionally lameness and primary thoracolumbosacral region pain coexist. When evaluated on the lunge, careful attention should be paid to the range of motion of the thoracolumbosacral region and the tail and contraction of the thoracolumbosacral epaxial muscles.

Reduced range of motion, and exaggerated contractions of the epaxial muscles, may reflect primary thoracolumbosacral region pain. Ideally, the horse should be assessed and ridden by its normal rider – if the horse is considered safe and the rider has sufficient confidence.

Some riders may have become frightened by their horse’s behaviour. In such cases it becomes a judgement call as to whether the horse is safe to be ridden by a more skilled rider. Bucking and kicking out, with the thoracolumbar region extended, is not typical of primary thoracolumbosacral region pain, and is more likely to reflect sacroiliac joint region pain8. Conversely, a series of humping-type bucks with the thoracolumbar region in flexion is more likely to reflect primary thoracolumbosacral region pain. Episodic shooting forwards, as if experiencing a sudden sharp pain, is most typical of sacroiliac joint region pain8, whereas bolting is a very non-specific sign that could reflect musculoskeletal pain from any source.

Comparison of the horse’s performance in rising versus sitting trot can be helpful. Alteration in posture and movement of the cervical and thoracolumbosacral regions in sitting trot may suggest primary thoracolumbosacral region pain. Comparison of canter and trot is also helpful; a canter quality that is worse than trot is suggestive of a component of sacroiliac joint region pain8.

The absence of response to systematic palpation does not preclude the presence of underlying pathological lesions causing pain. If other potential causes of pain have been excluded, survey radiography and ultrasonography of the thoracolumbosacral region, to include the spinous processes, articular process joints, vertebral bodies and symphyses and supraspinous ligament, should be performed.

Since a large proportion of horses have two or more impinging spinous processes, verification of the clinical significance of any findings must always be determined using diagnostic anaesthesia, whenever possible (Figure 2). Diagnosis may ultimately be a process of exclusion for some lesions, such as degenerative changes of the lumbosacral or lumbar 5-6 symphyses21.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is challenging to determine the cause(s) of ridden horse behavioural abnormalities and a systematic comprehensive approach, with knowledge of training principles and behavioural responses, is most rewarding.

References

- McGreevy PD and McLean AN (2007). Roles of learning theory and ethology in equitation, J Vet Behav 2(4): 108-118.

- Dyson S et al (2018). Development of an ethogram for a pain scoring system in ridden horses and its application to determine the presence of musculoskeletal pain, J Vet Behav 23: 47-57.

- Dyson S et al (2018). Response to Gleerup: understanding signals that indicate pain in ridden horses, J Vet Behav 23: 87-90.

- Dyson S et al (2018). Behavioural observations and comparisons of non-lame horses and lame horses before and after resolution of lameness by diagnostic analgesia, J Vet Behav 26: 64-70.

- Dyson S and Van Dijk J (2018). Application of a ridden horse ethogram to video recordings of 21 horses before and after diagnostic analgesia: reduction in behaviour scores, Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13029

- Dyson S et al (2019). Can veterinarians reliably apply a whole horse ridden ethogram to differentiate non-lame and lame horses based on live horse assessment of behaviour? Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13104

- Zimmerman M et al (2012). Close, impinging and overriding spinous processes in the thoracolumbar spine: the relationship between radiological and scintigraphic findings and clinical signs, Equine Vet J 44(2): 178-184

- Barstow A and Dyson S (2015).Clinical features and diagnosis of sacroiliac joint region pain in 296 horses: 2004-2014, Equine Vet Ed 27(12): 637-647.

- Greve L and Dyson S (2018). What can we learn from visual and objective assessment of non-lame and lame horses in straight lines, on the lunge and ridden? Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13016

- Licka T et al (2004). Influence of rider on lameness in trotting horses, Equine Vet J 36(8): 734-736.

- Greve L and Dyson S (2015). Saddle fit and management: an investigation of the association with equine thoracolumbar asymmetries, horse and rider health, Equine Vet J 47(4): 415-421.

- Dyson S et al (2015). Saddle fitting, recognising an ill-fitting saddle and the consequences of an ill-fitting saddle to horse and rider, Equine Vet Ed 27(10): 533-543.

- Bidstrup I (2018). Saddle trauma and the essentials of saddle fit, www.spinalvet.com.au (accessed 20 October 2019).

- Bondi A (2019). Evaluating the suitability of an English saddle for a horse and rider combination, Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13158

- Van Iwaarden A et al (2012). Topographical anatomy of the equine M cutaneous trunci in relation to the position of the saddle and girth, J Equine Vet Sci 32(9): 519-524.

- Bowen A et al (2017). Investigation of myofascial trigger points in equine pectoral muscles and girth-aversion behavior, J Equine Vet Sci 48: 154-160e1.

- Millares-Ramirez E and Le Jeune S (2019). Girthiness: retrospective study of 37 horses, J Equine Vet Sci 79: 100-104.

- Dyson S et al (2019). The influence of rider:horse bodyweight ratio and rider-horse-saddle-fit on equine gait and behaviour: a pilot study, Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13085

- Roost L et al (2019). The effects of rider size and saddle fit for horse and rider on forces and pressure distribution under saddles: a pilot study, Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13102

- Dyson S (2018). The influence of rider:horse bodyweight ratio on equine gait, behaviour, response to thoracolumbar palpation and thoracolumbar dimensions: a pilot study, Proc 14th International Society of Equitation Science Congress, Rome: 120.

- Boado A et al (2019). Ultrasonographic features associated with the lumbosacral or lumbar 5–6 symphyses in 64 horses with lumbosacral-sacroiliac joint region pain (2012–2018), Equine Vet Ed, https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13236