16 Mar 2022

Equine asthma – management, treatment and diagnosis advances

Ann Derham provides an overview of the causes of this issue, and summarises developments in management and treatment.

Figure 2. Horse wearing a nebuliser for treatment of lower airway inflammation.

Equine asthma is a disease caused by exposure to airborne environmental particles resulting in a lower respiratory inflammatory response (bronchospasm, mucus hypersecretion, decreased mucociliary clearance and inflammatory cell recruitment).

The disease is separated into a mild/moderate form, which is more common in young horses presenting with poor performance, while the severe form is more typical of older horses (older than seven years), and the predominant complaint is coughing with an increased respiratory effort after exposure to airborne particles. The incidence of the mild/moderate type is approximately 20% to 80%, and the severe form 11% to 17%.

Diagnosis of the severe form can be based on clinical signs and history. The mild-moderate form will require further diagnostics in the form of cytology from a bronchoalveolar lavage or a transtracheal wash. Treatment of these cases consists of alleviating the clinical signs and inflammation, usually with a corticosteroid, while environmental adjustments are critical for long-term management.

Equine asthma is a term used to describe a chronic, non-infectious, environmentally induced inflammation affecting the lower respiratory tracts of horses.

While the term “equine asthma syndrome” (EAS) is relatively new, the diseases it covers have long been recognised in horses: inflammatory airway disease (IAD), recurrent airway obstruction (RAO), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic obstructive pulmonary bronchiolitis (COPB), equine emphysema, heaves, and summer pasture-associated obstructive pulmonary disease (SPAOPD).

EAS is caused by exposure to airborne environmental particles that leads to a pulmonary inflammatory response; however, the response to these particles is different for individuals, with some having an inappropriately exaggerated response. This lower respiratory tract inflammation causes bronchospasm, mucus hypersecretion, decreased mucociliary clearance and inflammatory cell recruitment.

EAS is classified based on disease severity into a mild-moderate form (previously IAD), or a severe form (previously RAO, SPAOPD, COPD or heaves). According to recent literature, the mild/moderate type has an estimated prevalence of 20% to 80%, and the severe form 11% to 17 %1-3.

Diagnosis

The mild to moderate form is typically seen in horses in training, with the most common complaint from owners and trainers being poor performance, or slow recovery following exercise. The severe form is more common in older horses (older than seven years) and the predominant complaint is coughing, with an increased respiratory effort following exposure to hay or organic bedding (stabling on straw). These horses will also suffer from exercise intolerance and may have mucopurulent nasal discharge.

On clinical examination, horses with the mild/moderate form may not have any abnormalities on auscultation, whereas the severe form will typically have expiratory wheezes and inspiratory crackles. A re-breathing exam may be useful in working-up these cases (avoid in dyspnoeic/fractious animals). In severe cases, the history and clinical exam are usually sufficient for diagnosis; however, for the mild/moderate form and for confirmation of the severe form, further diagnostics are necessary:

- Endoscopy. This allows visualisation of the nasal passages, nasopharynx, larynx and trachea, and can help rule in or out concurrent issues elsewhere along the respiratory tract.

- Transtracheal wash (TW). This is done via an endoscope or percutaneously. The advantage of the scope is that it allows visualisation of the tract and is technically easier to perform. Make sure, if doing via the scope, that the scope tip does not contaminate your fluid sample. Where financial constraints exist, the percutaneous option may be more cost effective, whereby a 12g IV catheter and a dog urinary catheter are used.

- Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). The BAL is performed blindly or via an endoscope (Figure 1). This technique is carried out more routinely, as it is considered to be a more sensitive technique for identifying lower airway inflammation4.

- Cytology. Samples from either the BAL or TW can be used for this (Table 1).

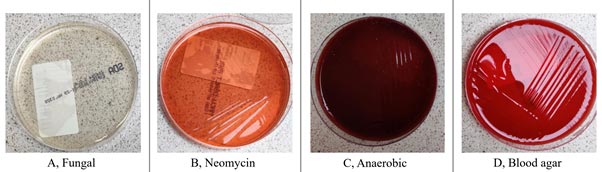

- Microbiology. A TW sample is required for this. Typically, these samples are plated on blood agar, anaerobic, fungal, and neomycin plates (Figure 1).

| Table 1. Suggested reference ranges for normal and equine asthma BAL samples5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory cells | Normal | Mild/moderate equine asthma | Severe equine asthma |

| Neutrophils | ≤ 5% | > 10% | > 25% |

| Mast cells | ≤ 2% | > 5% | ≤ 2% |

| Eosinophils | ≤ 1% | > 5% | ≤ 1% |

Management/treatment

Originally, a lot of these cases were treated with antibiotics, but since tracheal washes and bronchoalveolar lavages have become more routinely performed, cytology has resulted in a move away from antibiotics, unless indicated. The aim of managing and treating lower respiratory tract inflammatory cases (mild-moderate, severe) is to alleviate the inflammation and clinical signs, and to remove the inciting cause from the horse’s environment.

Addressing all three components is the key to successful management. Failure to address the environmental component will result in very short-term improvements, if any. A critical point to stress to clients is no quick fix exists, and that this will be a long-term management issue, especially when taking into account racing/competition withdrawals.

Corticosteroids (dexamethasone, prednisolone, fluticasone) are shown to improve airway inflammation, especially when coupled with environmental controls. These have become the cornerstone of treatment and can be given intravenously, intramuscularly, orally, or inhaled (Figure 2). Inhalation is superior to other routes as it achieves a higher concentration of the drug directly into the lower airway at the site of inflammation. Always remember to warn clients of potential adverse side effects when using any corticosteroids.

In terms of the environment, the goal of managing the horse’s environment is to reduce the dust concentration in the horse’s breathing space, as airborne organic dust plays a critical role in the development and progression of equine asthma. It has also been shown that the type of bedding and forage used can pose significant risk factors for developing fungal contamination and EAS. Pro-inflammatory agents and irritants include bacterial endotoxins, moulds, microbial toxins, forage mites, plant debris, inorganic dust (gallops) and ammonia.

Therefore, it is important, when speaking to clients, that they understand and try to avoid common oversights when addressing their horse’s environment. These include:

- Poor ventilation, such as sharing airspace with horses not kept in the same environment.

- Keeping hay/muck heaps close to the stable, deep litter bedding, mucking out/sweeping alleys while the horse is in the stable.

- Feeding mouldy haylage/hay at the bottom of the feeder, and instead using a hay net/not feeding from a clean floor.

- Homemade steamers.

Corticosteroids take time to work, and if severe bronchoconstriction is present, bronchodilators and mucolytics may be required for rapid improvement, giving time for the corticosteroids to take effect.

- Bronchodilators (clenbuterol) can be used to acutely treat bronchospasm and mucus accumulation, but must be used in conjunction with corticosteroids, as they do not treat underlying inflammation.

- During severe inflammation, increased amounts of mucus is produced, which is highly viscous. Mucolytics (acetylcisteine, dembrexine), as an adjunctive therapy to corticosteroids, may help remove this increased volume from the lower respiratory tract.

Repeat bronchoalveolar washes may be required to assess response to treatment, and response to environmental changes.

Advances in treatment

Ciclesonide is a novel corticosteroid used in the Equihaler. This is a prodrug that becomes activated when it reaches the airway epithelium, and so is a targeted treatment. The major advantages of this type of drug are its reduced systemic concentrations, which should reduce the chances of having undesirable effects.

This product is used in a “soft mist” inhaler, which works on the premise that very small particles (below 5μm) are optimal for deposition deep in the lungs, and the low velocity action results in a longer duration of release, which appears to be better for asthmatic breathing patterns in horses.

Summary

Mild-moderate EAS should be considered in cases of poor performance. The severe form may be diagnosed based on history and clinical signs alone. However, bronchoalveolar washes are the most sensitive diagnostic technique, and can also be used to monitor response to treatment and environmental management. Corticosteroids are key to targeting the lower respiratory tract inflammation and can be delivered via a number of routes, with inhalation the most common current method. Environmental adjustments are critical to successful long-term case management.

References

- Ivester KM, Couëtil LL and Moore GE (2018). An observational study of environmental exposures, airway cytology, and performance in racing thoroughbreds, J Vet Intern Med 32(5): 1,754-1,762.

- Hotchkiss JW, Reid SWJ and Christley RM (2007). A survey of horse owners in Great Britain regarding horses in their care. Part 2: risk factors for recurrent airway obstruction, Equine Vet J 39(4): 294-300.

- Ivester KM, Couëtil LL and Zimmerman NJ (2014). Investigating the link between particulate exposure and airway inflammation in the horse, J Vet Intern Med 28(6): 1,653-1,665.

- Pirie RS (2014). Recurrent airway obstruction: a review, Equine Vet J 46(3): 276-288.

- Couëtil LL, Cardwell JM, Gerber V, Lavoie JP, Léguillette R and Richard EA (2016). Inflammatory airway disease of horses – Revised Consensus Statement, J Vet Intern Med 30(2): 503-515.