3 Jun 2025

Equine castration complications

Kayleigh Cook CertAVP(ESST), PGCertVPS, PGCAP, FHEA, MRCVS details the short-term and long-term risks of this procedure, whether performed in the field or a hospital setting.

Image: julia_siomuha / Adobe Stock

Castration is a commonly performed procedure in equine practice, with a variety of techniques.

It is also a procedure with a high rate of complications; therefore, it is vital that practitioners are aware of, and equipped to both reduce the risk of and deal with, the potential complications that may arise from this procedure.

Technique

A variety of techniques have been reported in the literature for castration of equids.

All techniques can be performed under standing sedation or general anaesthesia (GA), in both hospital and field settings. Most techniques involve the creation of scrotal incision, which is left to heal by secondary intention following the procedure (Baldwin, 2023).

Open castration techniques involve an incision into the parietal tunic of the testis, which is then left open following castration. Following an open castration, the parietal tunic remains within the horse. This technique involves the least dissection and is commonly performed under standing sedation (Schumacher, 2019).

With closed techniques, the parietal tunic is not incised and is removed along with the testis and epididymis. A proximal ligature is used to seal the parietal tunic and, therefore, ensures no communication between the surgery site and the abdomen (Schumacher, 2019).

Semi-closed techniques also exist that involve the creation of an incision into the parietal tunic; however, the parietal tunic is still removed along with the testis and epididymis. This technique involves significantly more tissue handling than other techniques. Both closed and semi-closed techniques are usually performed under GA (Schumacher, 2019).

Complication rates

Reported complication rates of equine castration range from between 10% to 60% of all procedures (Hodgson and Pinchbeck, 2019; Kilcoyne et al, 2013; Robinson et al, 2023; Rosanowski et al, 2018).

Complications vary from mild to life threatening and can occur minutes to years after the castration event (Baldwin, 2023). Complication rates vary with technique and the environment the procedure is performed in. In one study, complication rates were reported as 22% for standing castrations performed in the field versus 2.1% for castrations performed recumbent under aseptic conditions (Mason et al, 2005).

In another study by Kilcoyne et al (2013), castration before using a semi-closed technique had significantly higher odds of complication versus those performed using a closed technique. Other studies have shown less clear association between the technique utilised for castration and subsequent complications (Hodgson and Pinchbeck, 2019).

Standing castration has significantly reduced costs, as well as reduced risk of anaesthetic recovery events, versus castration performed under GA (Mason et al, 2005). However, human safety factors also must be considered. Cases in very small or fractious patients are often more safely performed under GA (Baldwin, 2023). The procedure is commonly performed by practitioners in field settings, both under GA and as a standing sedated procedure.

Intraoperative complications, such as a break in sterility or poor surgical technique, have been shown to be a consistent risk factor for complications (Baldwin, 2023; Hodgson and Pinchbeck, 2019). Clear associations between increased risks of castration complications in donkeys versus horses (Sprayson and Thiemann, 2007) and in animals of increasing age (Hodgson and Pinchbeck, 2019) have been demonstrated in the literature.

When complications develop post-castration in equines, swelling, infection and haemorrhage tend to be the most common (Robinson et al, 2023).

Haemorrhage

Haemorrhage is a very common complication in the preoperative and immediate postoperative period. However, the incidence of excessive haemorrhage is very low, reported in the literature at rates of around 2.4% (Kilcoyne et al, 2013).

Steady postoperative dripping of blood at a rate that is easily countable is expected. Further treatment should be considered if this rate increases or continues for a significant period postoperatively. The testicular artery is the most common source of haemorrhage; however, significant bleeding can also occur from the testicular vein and dermal vessels.

Risk factors include older horses and donkeys, as these animals have larger spermatic vessels; therefore, closed castration with a proximal ligature is recommended in these animals (Baldwin, 2023). Other risk factors include breaks in asepsis, poor surgical technique, haematomas and poorly operating or operated equipment (Hodgson and Pinchbeck, 2019). Treatment includes direct pressure by packing the site if the vessel cannot be visualised, but ideally clamping and ligation of the bleeding vessel should be performed. Topical and systemic coagulation agents have also been reported, with variable success rates.

If haemorrhage is significant, blood transfusion may need to be considered. Rarely, some horses haemorrhage into the abdomen, and so will not have externally visible blood loss; this may be detected ultrasonographically (Baldwin, 2023).

Oedema

Oedema of the prepuce and scrotum is a common complication (Figure 1), occurring in up to 70% of castrations reported in the literature in the first days to weeks postoperatively (Rosanowski et al, 2018).

Many factors give rise to this complication, including poor surgical technique creating undue tissue trauma, inadequate postoperative drainage and movement, postoperative infection and excessive haemorrhage.

Good aseptic surgical technique with a clear knowledge of anatomical landmarks will reduce surgical trauma.

Creating adequate surgical incisions at the most ventral portion of the scrotum will promote drainage, and this can be augmented by owners encouraging regular movement with turnout and light exercise. Low-pressure cold hosing can be useful as an adjunct to control swelling if well tolerated (Robinson et al, 2023). Preoperative and postoperative NSAIDs will provide analgesia; therefore, increasing the animal’s likelihood to move and reduce swelling, as well as promoting a reduction in inflammation (Baldwin, 2023).

If a seroma forms, studies report re-establishment of drainage useful in reduction of swelling (Mason et al, 2005).

Early reduction of swelling can reduce the risk of other complications such as infections; therefore, early treatment is vital (Baldwin, 2023).

Infection

Postoperative swelling is one of the most common causes of infection, as well as poor surgical or aseptic technique at the time of surgery.

Swelling causes a reduction in drainage from the surgical site, increasing the risk of bacteria becoming trapped and proliferating at the surgical site. Local infection often presents as hot, painful swelling at the surgical site and local area, alongside discharge from the site. Discharge may not be present if the surgical incision has sealed. Systemic signs of infection include pyrexia, dullness, lameness or a purulent discharge (Baldwin, 2023).

Treatment is similar to the treatment for oedema, but antimicrobials are likely also warranted, ideally guided by culture and sensitivity (Mason et al, 2005). Clostridial infection – particularly tetanus – can occur in unvaccinated horses with a high mortality rate, so it is vital horses have appropriate administration of tetanus anti-toxin and toxoid prior to castration (Baldwin, 2023).

Scirrhous cord

Chronic infection of the spermatic cord is an uncommon complication (Duggan et al, 2020). It can occur as a sequela of infection of the surgical site, but has also been reported to occur following use of non-sterile surgical instruments or a contaminated surgical ligature.

Staphylococcus species is the most common bacteria cultured from these cases (Kilcoyne et al, 2013). Cases typically present with scrotal and preputial oedema, pyrexia and a palpable thickening of the spermatic cord, occasionally palpable rectally (Duggan et al, 2020).

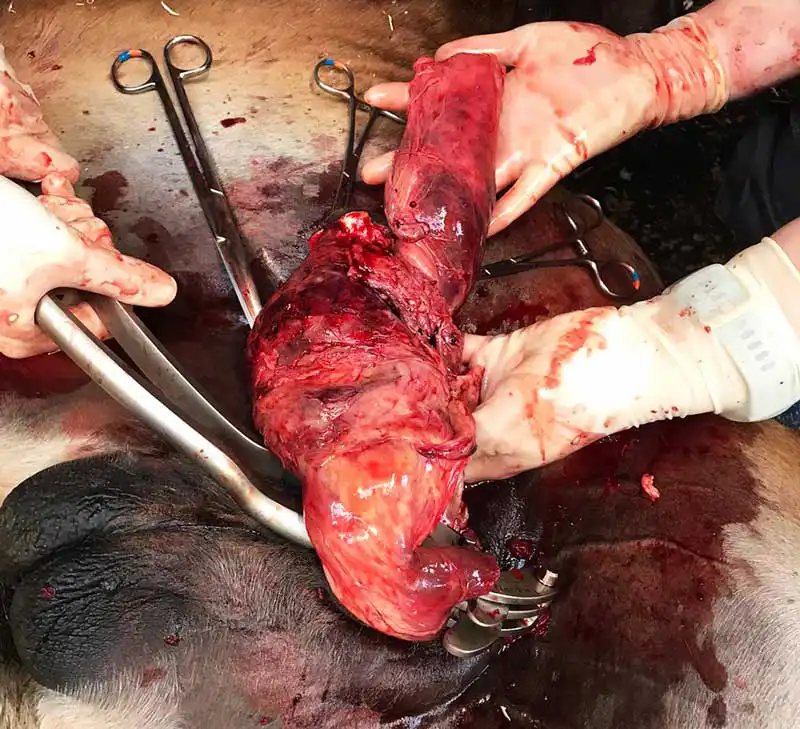

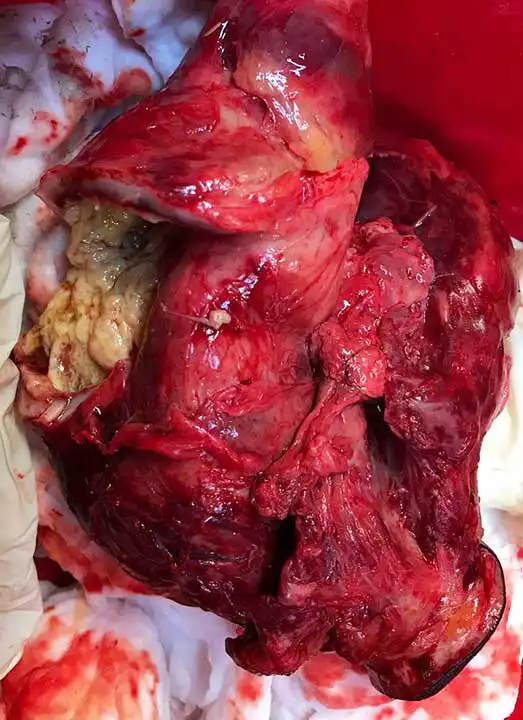

Some cases may present with a visible stump of spermatic cord forming a chronic sinus tract at the original surgical site (Figure 2). Most animals present within four months of castration, but cases have been reported up to 10 years post-castration (Duggan et al, 2020).

Medical treatment has been reported; however, generally surgical excision is required for resolution. The infected portion of spermatic cord should be excised, and the scrotal incisions left open to heal by secondary intention (Figures 3 and 4; Baldwin, 2023).

Peritonitis

Any infection of the castration surgical site can potentially lead to ascending infection and septic peritonitis, but this is rare.

Clinical signs include pyrexia, dullness, colic signs and occasionally diarrhoea. Diagnosis can be confirmed by performing abdominocentesis.

Medical treatment can often be provided with broad-spectrum antimicrobials and NSAIDs, with peritoneal lavage required in poorly responding cases (Baldwin, 2023).

Penile damage

Penile damage is an uncommon complication and generally occurs from a surgical error or as an indirect result of scrotal swelling or paraphimosis. A poor knowledge of anatomy can lead to surgical error and incision of the penis instead of a testicle, which can have serious complications (Schumacher, 2019).

Prolonged swelling or paraphimosis can result in permanent penile paralysis if not resolved in a timely manner (Baldwin, 2023).

Hydrocoele

Hydrocoele is a rare, idiopathic complication occurring months to years following castration (Schumacher, 2019). Peritoneal fluid accumulates in the parietal tunic; therefore, it only occurs in horses that have been castrated using an open method.

Diagnosis is often by palpation or ultrasound examination. No treatment is required, but surgical resection can be performed for aesthetic reasons (Baldwin, 2023).

Incomplete castration

Castration is not a guarantee in the elimination of stallion-like behaviour and it is important that this discussion is held with owners prior to the procedure being performed.

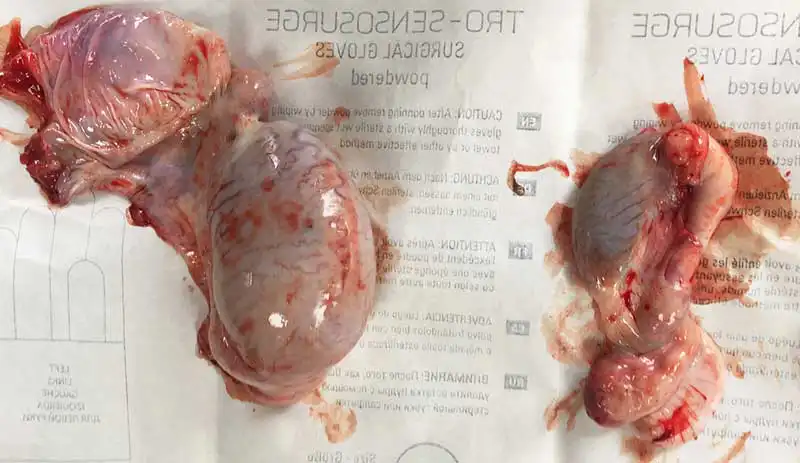

Continued stallion-like behaviour can also occur if the surgeon mistakenly removes the epididymis instead of the testicle (Baldwin, 2023).

Some animals can have markedly asymmetrical and small testicles, which can make this error much more likely (Figure 5). A clear understanding of anatomy prior to the application of emasculators can help to reduce the risk of this complication occurring.

Evisceration

Evisceration is the most serious complication of castration, with a reported incidence of 0.3% to 4.8% in the literature (Hodgson and Pinchbeck, 2019; Kilcoyne et al, 2013; Hinton et al, 2019). This generally occurs within minutes to hours of the procedure, but has been reported to occur as long as 12 days after castration (Boussauw and Wilderjans, 1996).

Breed is a known significant risk factor, with draught horses, standardbreds and Tennessee walking horses demonstrating a greater incidence (Hinton et al, 2019).

Other risk factors include animals less than six months old, large inguinal rings and pre-existing inguinal hernias (Baldwin, 2023). Prevention is focused on a good clinical history and examination, ensuring that any horses at risk are castrated with a closed technique utilising a proximal ligature (Hinton et al, 2019).

Treatment of this complication is either euthanasia or surgical reduction of the herniated segment of small intestine at a referral facility. Careful preparation of the herniated small intestine for transport is vital to improve the chance of success of success (Baldwin, 2023).

Omental herniation

Omental herniation is a less concerning complication than evisceration and most cases can be managed by emasculation of the prolapsed omentum proximally with a good prognosis. However, it is vital to examine the vaginal rings rectally to ensure that no small intestine has crossed the vaginal ring.

The horse should be box rested and monitored for several days after the procedure to reduce the risk of further prolapse. If a large amount of omentum is prolapsed or prolapses continue to occur, owners should consider referring the horse for closure of the superficial inguinal ring (Baldwin, 2023).

Conclusions/prevention of complications

Many of the most common complications discussed in this article can be mitigated by good surgical technique and a thorough understanding of the anatomy.

While most commonly seen complications are mild and treatable, early recognition and management of complications will reduce the risk of some more serious complications. A thorough history and preoperative assessment will also reduce risks further (Baldwin, 2023).

While we should strive to optimise our practice to reduce the risk of complications wherever possible, complications are common with this procedure – particularly for most practitioners performing this as a field procedure. Therefore, it is important owners are counselled in this to ensure clear expectations.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 22, Pages 16-18

References

- Baldwin CM (2023). A review of prevention and management of castration complications, Equine Vet Educ 36(2): 97-106.

- Boussauw B and Wilderjans H (1996). Inguinal herniation 12 days after a unilateral castration with primary wound closure, Equine Vet Educ 8(5): 248-250.

- Duggan M et al (2020). The clinical features and short-term treatment outcomes of scirrhous cord: a retrospective study of 32 cases, Equine Vet Educ 33(8): 430-435.

- Hinton S et al (2019). Prevalence of complications associated with use of the Henderson equine castrating instrument, Equine Vet J 51(2): 163-166.

- Hodgson C and Pinchbeck G (2019). A prospective multicentre survey of complications associated with equine castration to facilitate clinical audit, Equine Vet J 51(4): 435-439.

- Kilcoyne I et al (2013). Incidence, management, and outcome of complications of castration in equids: 324 cases (1998–2008), J Am Vet Med Assoc 242(6): 820-825.

- Mason BJ et al (2005). Costs and complications of equine castration: a UK practice-based study comparing “standing nonsutured” and “recumbent sutured” techniques, Equine Vet J 37(5): 468-472.

- Robinson N et al (2023). Post-operative complications following equine castration: a prospective clinical audit, Equine Vet J 55(S58): 21.

- Rosanowski SM et al (2018). Open standing castration in Thoroughbred racehorses in Hong Kong: prevalence and severity of complications 30 days post-castration, Equine Vet J 50(3): 327-332.

- Schumacher J (2019) Testis, Testis. In Auer JA et al (eds), Equine Surgery (5th edn), Elsevier Health Sciences, Amsterdam: 994-1,034.

- Sprayson T and Thiemann A (2007). Clinical approach to castration in the donkey, In Pract 29(9): 526–531.