10 Jul 2023

Fleur Whitlock BVetMed, MSc, MRCVS, Victoria Colgate MA, VetMB, MSc, MRCVS, and Richard Newton BVSc, MSc, PhD, FRCVS, of the Equine Infectious Disease Surveillance team, reveal the current situation here with the endemic disease.

Image: © stokkete / Adobe Stock

Equine influenza (EI) remains a highly contagious respiratory virus and, in immunologically naive populations, can spread rapidly and result in a high level of morbidity – and occasionally mortality.

During 2019, Europe experienced an epidemic of influenza in which hundreds of horses were confirmed positive, with suspicions that thousands were actually affected, but never tested1.

In a population with adequate immunity to current circulating strains, through either natural exposure or vaccination, clinical disease is ordinarily mild and signs may be transient (mild pyrexia, lethargy and slight nasal discharge).

This is often the case in the UK, where EI is an endemic disease and, in the 2019 European outbreak, vaccines did largely impart an adequate level of protection in those populations where they were optimally used.

In contrast, concurrent reports from west Africa detailed a similar epidemic, but with disease being fatal in more than 65,000 donkeys and horses. This demonstrated the potentially catastrophic outcome of EI spread in an at-risk, naive population2.

Circulating influenza viruses evolve continually due to RNA genetic mutations giving rise to antigenic changes (so-called antigenic drift), albeit these changes arise more slowly in EI compared to human influenza viruses.

The potential for EI viruses to diverge beyond the scope of protection imparted by EI strains included in current commercially available vaccines is an ever-present concern. In addition to antigenic drift, new subtypes and strains can appear as a result of co-infection by different influenza viruses, and subsequent re-assortment of the segmented genome. This is the so-called “antigenic shift”.

These characteristics ensure influenza viruses are ever-changing and, therefore, must be monitored and reacted to via surveillance activities. The outputs from surveillance inform optimal control and prevention measures, in turn reducing the risk of potentially catastrophic outcomes.

The UK is one of the only countries in the world to have subsidised EI testing, available through the support of an industry-funded surveillance initiative.

The Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) equine influenza surveillance scheme is overseen by epidemiologists at Equine Infectious Disease Surveillance (EIDS) and equine virologists, all now based in the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge.

Veterinary surgeons who have subscribed to the scheme are encouraged to submit nasopharyngeal swabs from horses, both vaccinated and unvaccinated, displaying clinical signs that could be consistent with equine influenza, and have these PCR tested for free at the scheme’s designated laboratory.

It is important to remember that even when adequate similarity is seen between circulating field strains and vaccine strains, the vaccine does not necessarily provide 100% protection against infection and subsequent clinical disease. Therefore, veterinary surgeons are encouraged to sample vaccinated horses, even if they only have mild clinical signs, as this could be EI and an early indication of emerging vaccine issues.

The team at EIDS also encourages other veterinary diagnostic laboratories making positive diagnoses of EI, and their submitting veterinary surgeons, to respectively contribute positive samples to the University of Cambridge virologists for further virological investigation, and to submit case and outbreak data to EIDS epidemiologists.

This information is usually shared on an anonymised county-level basis to inform stakeholders with regard to current EI threat levels, encourage ongoing vigilance and increase surveillance uptake and submissions. In addition, virological analysis is used to monitor genetic and antigenic changes in the virus, comparing them through space and time, and evaluating cross-protection from current commercially available vaccines.

Viral isolates obtained through the surveillance by the Cambridge virologists may occasionally also be made available to vaccine manufacturers for studies to update influenza vaccine strains and develop new products. Data obtained through this UK surveillance is contributed annually to the globally representative Expert Surveillance Panel on Equine Influenza Vaccine Composition, which is overseen by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH, formerly the OIE). The quality and extent of surveillance programmes are country specific, and vary depending on available resources, equine populations and disease statuses.

Many countries struggle to implement successful surveillance due to a variety of reasons that may include lack of funding, low owner perception regarding the benefits of diagnostic testing, a lack of commercial laboratory availability or low engagement with surveillance. EI surveillance relies on the voluntary detection and reporting of laboratory-confirmed cases, with multiple factors influencing the success of this method.

Veterinary surgeons in the UK are encouraged to continue to raise awareness among their clients about the benefits of veterinary involvement in suspected EI cases, to limit spread on, and beyond, premises. They are also advised to inform premises on the bigger picture of EI control and prevention.

During the 2019 European outbreak, although the infecting Florida clade 1 virus was not novel and was considered sufficiently similar to vaccine strains, environmental factors were considered important in facilitating viral spread.

Increased horse movements and mixing of infected with susceptible animals in the spring and summer months – particularly at gatherings that did not mandate vaccination as an entry requirement or have a biosecurity policy in place – were considered influential factors in disseminating infection and manifesting disease. These factors, coupled with recognised low overall population-wide vaccine coverage in the UK, probably provided the perfect storm for the emergence of an epidemic1.

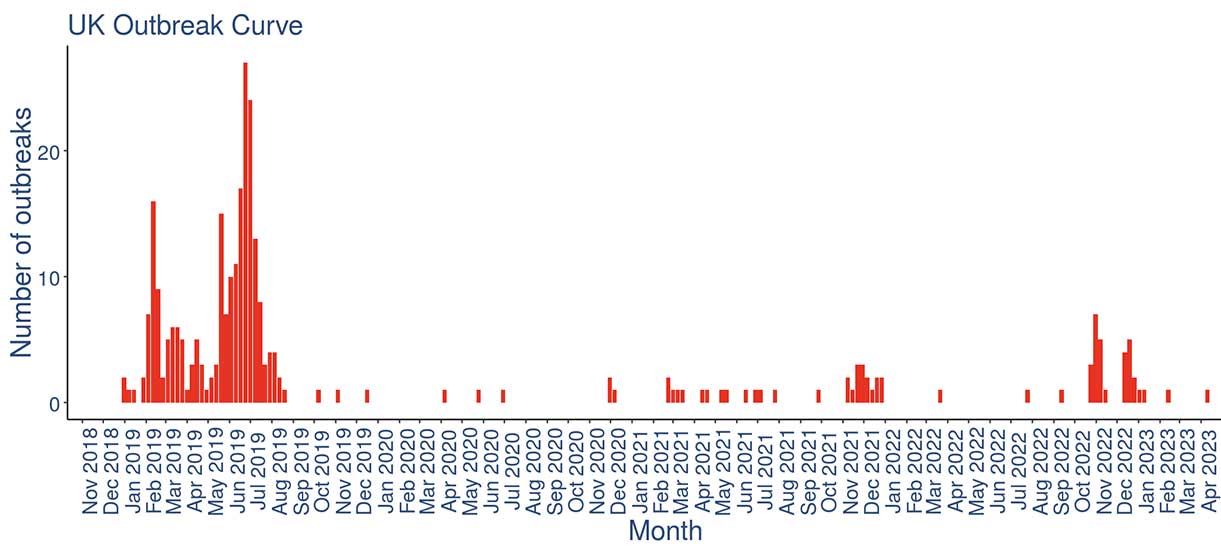

Similarly, during October and November 2022, although not on the scale of that seen in 2019, two significant increases in EI cases above baseline levels were seen – with 27 laboratory-confirmed outbreaks reported during this period3 (Figure 1).

The majority of the outbreaks involved unvaccinated horses and were associated with new arrivals to the affected premises – often from elsewhere in the UK and after purchase through sales markets – or involving animals that had been just imported into the country. This once again highlights the movement and gathering of horses represents a key opportunity for the spread of infectious diseases like EI – especially if appropriate precautions and preventive measures are not followed.

It is imperative that all new arrivals to a yard are vaccinated against EI (ideally at least two weeks beyond the second vaccine in the primary course, or within six months of a booster). The animals should also be quarantined in a designated isolation box for at least 14 days (ideally 21 days) and closely monitored. This should include temperature taking and recording at least once a day (and ideally twice a day). This will enable rapid detection of clinical signs should they occur, as well as ensuring early involvement of a veterinary surgeon to obtain a diagnosis and implement control measures to limit onward spread. Similarly, vaccination requirements and health checks before horses are allowed to enter a sales premises will help to reduce disease transmission events.

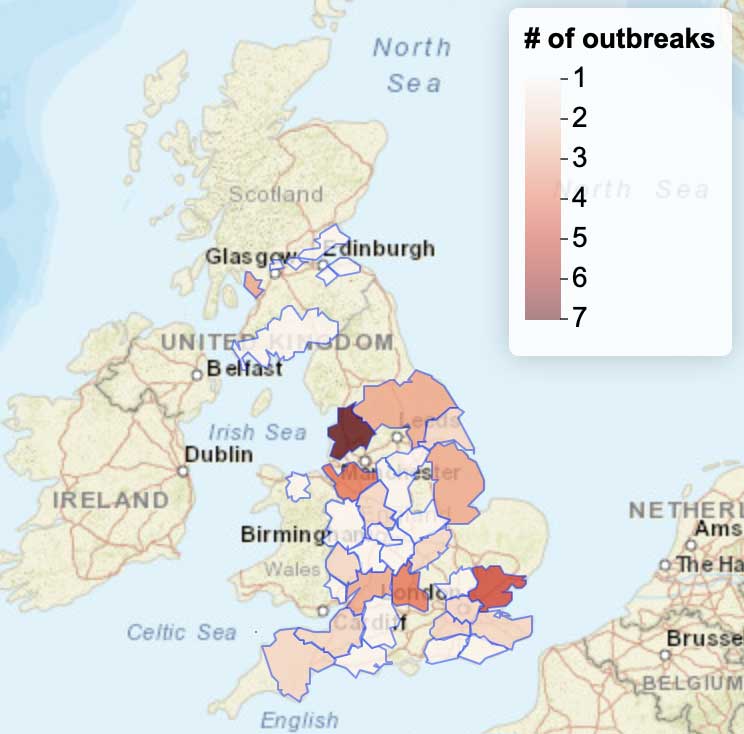

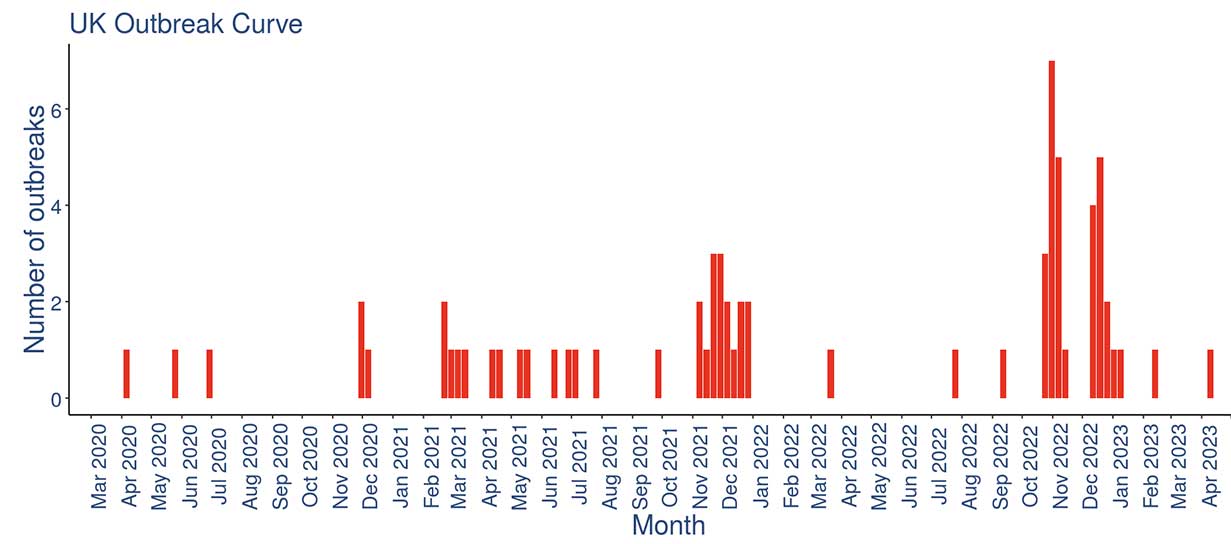

Figures 1 to 3 show EI activity in the UK over the past few years, with data obtained from the UK EI surveillance scheme.

An additional challenge to safeguarding the UK equine population from EI of late has been vaccine availability. As outlined in an editorial4, in August 2022 Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health experienced a problem with a technology upgrade that meant that ProteqFlu vaccines could not be released to wholesalers. As the product is one of just three EI vaccines available in Europe, this led to significant shortages, as the wholesaler stocks ran out and could not be resupplied until the end of October.

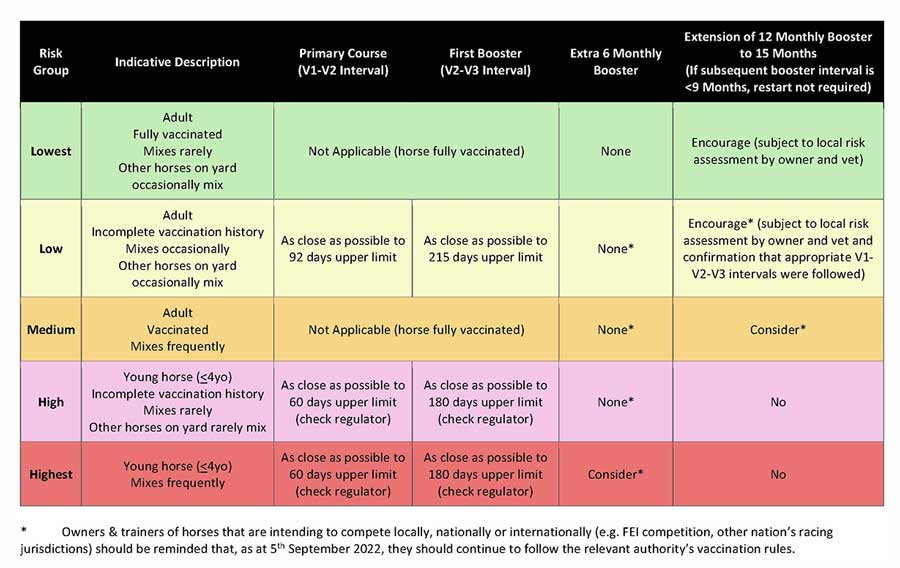

In response to the issue, a working group, convened by the BEVA, elucidated a protocol for vaccine administration on an at-risk basis (Figure 4) that would hopefully ensure all horses remained as well protected as possible, while additionally and importantly allowing equestrian competitions to continue.

Although the prompt action and workable solution may be seen as successful, with no notable EI outbreaks reported during the period of vaccine shortage, it unfortunately necessitated a most unwelcome extension of intervals between vaccine doses in vaccination protocols.

This was in stark contrast to the recent formal adoption of six-monthly, rather than annual, booster requirements by many of the sporting authorities as a condition for competition entry.

Indeed, following the shutdown of racing for six days in the face of the 2019 EI outbreaks, the British Horseracing Authority (BHA) adopted shorter booster intervals – a policy that was quickly adopted by several racing jurisdictions internationally, and aligned more closely with the long-established International Equestrian Federation (FEI) ruling that horses had to be vaccinated within six months and 21 days of competition5. The EIDS group has highlighted the benefits of six-monthly vaccination over annual boosters in terms of maintaining EI antibody levels, and maximising protection in the face of an imperfect vaccine that induces differing individual immunological responses to its administration5. It is now evident that the temporary vaccine shortage experienced in autumn 2022 has badly damaged the message to stakeholders around the better protection afforded by six-monthly boosters – and, indeed, it will probably take another major EI epidemic affecting vaccinated horses before the warning is heeded.

As we have already seen, EI vaccines are imperfect, supply problems could re-occur and with vaccine updates potentially taking many years to reach end users, it is paramount to quickly detect and evaluate important viral changes as they emerge.

All of this is only possible through ongoing surveillance, and horse owners and first opinion veterinary surgeons both play a critical role in surveillance. EIDS relies on horse owners, and their vets, who have daily contact with our equine population to recognise clinical problems and the potential for EI in their animals and patients. They should obtain appropriate samples and report positive laboratory-confirmed results. Only then is the circle of surveillance completed.

Other species and industry sectors have witnessed first hand the challenges posed by influenza viruses, with avian influenza (AI) in the UK impacting poultry and egg production, as well as the requirement to house backyard poultry bringing contentious challenges for many. Importantly, the continued widespread emergence of AI globally has led to increasing reports of cross-species transmission events, including a growing number of wildlife species, which, in turn, may act as sources of infection for other host species.

Consequently, a novel non-equine influenza virus spilling over into horses remains a major concern, although it is virtually impossible to practically predict if, what, when and how this may occur.

Accordingly, influenza viruses of any species should never be far from our minds, and the zoonotic potential of these influenza viruses should always be recognised.

Finally, if COVID has taught us anything, it is of the need, if possible, to avoid global pandemics, irrespective of the species concerned. With respect to horses, it should be noted that, after humans, horses are the most widely and rapidly travelled species on the planet and, as such, a novel EI virus, without protection from vaccines, will be likely to escalate swiftly to become a global equine pandemic.

The following outlines how veterinary surgeons can sign up for free EI PCR testing, sign up to infectious disease alerts and engage with all the surveillance platforms overseen by the EIDS industry-funded disease surveillance group.

To sign up to the HBLB equine influenza surveillance scheme for free PCR testing, visit https://equinesurveillance.org/fluenrol

For equine infectious disease outbreak reporting and free advice, telephone epidemiologists at EIDS on 01223 766496 or email [email protected]

The International Collating Centre (ICC) online interactive reporting platform is available at https://app.jshiny.com/jdata/icc/iccview or to sign up to receive ICC outbreak reports, email [email protected]

Equine influenza online interactive reporting platform is available at https://app.jshiny.com/jdata/equiflunet/equiflunet

To sign up to receive Tell-Tail text message alerts (outbreak reports for equine notifiable diseases, influenza and EHV-1 abortion/neonatal foal death/neurological disease), register your details at www.telltail.co.uk (sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim).