7 Apr 2020

Equine gastrointestinal disorders – obtaining a successful diagnosis

Karin Kruger provides tips to help general practitioners assess colic patients and reviews literature on common treatments.

Image: Kseniya Abramova / Adobe Stock

Acute colic is the most common equine veterinary emergency and the most common gastrointestinal disorder. Thankfully, the vast majority of cases will be amenable to medical management.

To provide the best service to our clients and patients, we should be able to communicate the likely potential outcomes, complication risks and potential costs involved in treating various types of colic. These facts should ideally be established before emotive emergencies arise.

Importantly, if addressed in a timely fashion by a competent team, most types of colic and colic surgery should have an excellent prognosis.

If your practice does not provide the full range of medical and surgical colic treatments required by your patients, the author would encourage you to contact nearby referral facilities for cost estimates, as well as survival and complication rate data for each hospital, to select the optimal facility for referral.

History – including management, medications and recent changes – signalment and colic examination can reveal many clues to assist the practitioner.

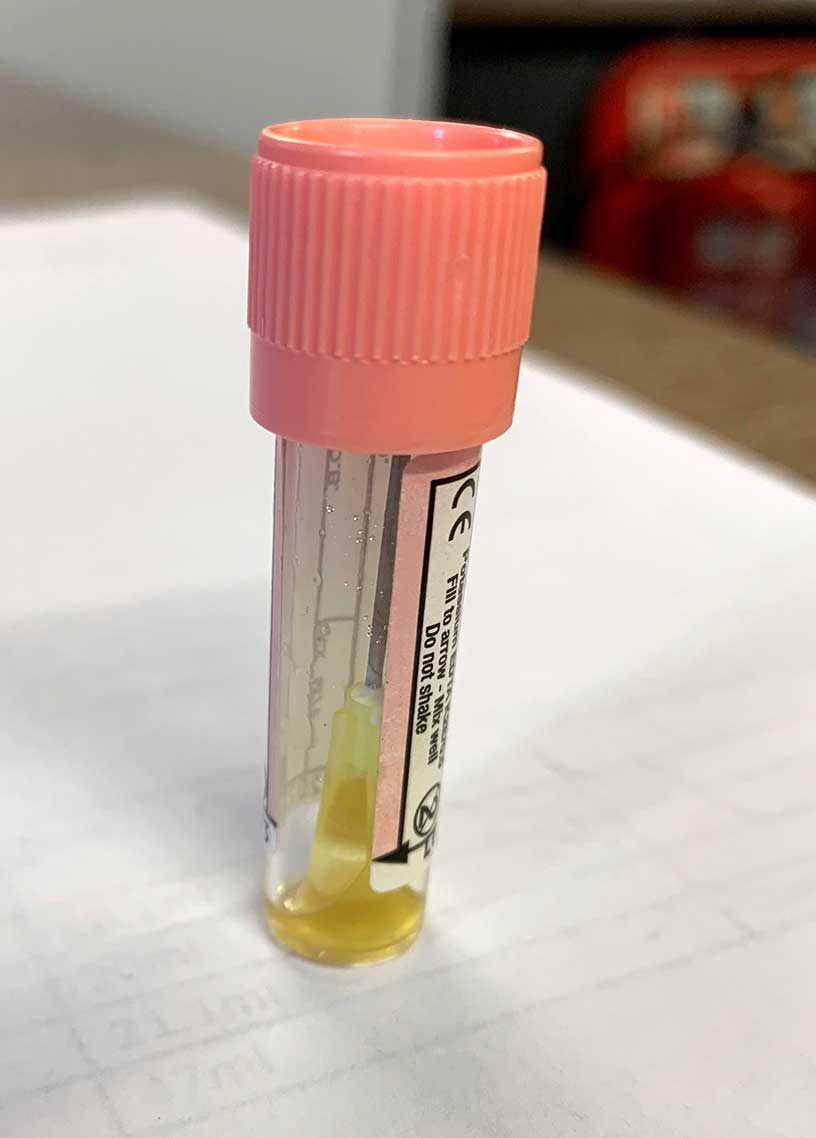

A first opinion colic examination may comprise a full physical examination, rectal examination, nasogastric intubation and abdominocentesis. This can be complemented by abdominal ultrasound, haematology and serum biochemistry.

Classifying colic patients to guide treatment

To guide selection of the most appropriate treatment, the author finds it helpful to classify colic horses into one of the following categories:

- non-strangulating large colon obstructions (impaction or displacement), including simple disturbances (for example, spasmodic/gas colic)

- non-strangulating small intestinal obstructions (for example, ileal impaction or proximal enteritis)

- inflammatory/infectious conditions (for example, peritonitis or enterocolitis)

- strangulating large or small intestinal obstructions

Any horse with severe or persistent pain (even mild persistent pain) where a specific diagnosis is not established, horses with no gut sounds, a horse with haemodynamic deterioration despite treatment, and those with suspected strangulating intestinal lesions should immediately be referred for further diagnostic evaluation and/or surgical exploration of the abdomen.

The single most important determination of outcome for a surgical colic patient is the time from the onset of clinical signs to surgical correction. Taking a “wait and see” approach when uncertainty exists about whether surgery is necessary will waste valuable time in patients where owners are amenable to referral.

Horses with acute, simple intestinal disturbances will often have unremarkable physical examination parameters. Gut sounds may be slightly decreased, normal, slightly increased or “gassy”, but are usually not absent – especially not after administration of flunixin. Horses are haemodynamically normal, and respond very well to small doses of hyoscine butylbromide and/or flunixin.

Non-strangulating large intestinal obstructions can have characteristic rectal findings. Pelvic flexure impactions are readily palpable. Unless gas distention is severe, left dorsal displacement can be palpated by following a colonic taenial band towards, or into, the nephrosplenic space. The spleen is displaced medially and ventrally, and access to the left kidney may be obstructed by the colon.

Right dorsal displacements may have a horizontal taenial band running left to right across the abdomen. They also frequently have elevated gamma‑glutamyltransferase on serum biochemistry.

Retroflexion of the pelvic flexure should be suspected when the pelvic flexure cannot be palpated, but the horse is showing signs consistent with a non‑strangulating large intestinal obstruction.

Gas distention associated with intestinal obstructions can be so severe as to preclude detailed rectal evaluation.

It is important to differentiate a large colon impaction, which is relatively easier to treat, from a caecal impaction, which is both more difficult to resolve and may rupture without much warning. If accessible, identifying the medial caecal band – which runs cranioventrally from the dorsal body wall – can help identify the caecum.

If the author is unsure whether a viscus is colon or caecum, she will try to run her hand over the top of it. If it is separate from the dorsal body wall then it is the colon. If she can’t get over the top of it because it is attached to the dorsal body wall then it is the caecum.

Both strangulating and non‑strangulating obstructions of the small intestine are associated with severe colic signs, small intestinal distention and varying amounts of reflux. Non‑strangulating small intestinal obstructions can be physical (for example, ileal impaction) or functional (for example, enteritis).

Enteritis cases also fit into the inflammatory gastrointestinal disorder category. Horses with enteritis tend to have larger volumes of reflux and are usually more depressed than painful after gastric distention is relieved. Their inflammatory markers (serum amyloid A and fibrinogen) are elevated. Ultrasound is extremely useful to detect subtle changes in small intestinal motility, content and wall thickness.

Horses with a strangulated bowel initially exhibit severe colic signs, but will have a period where owners may mistake an apparent improvement in comfort with overall improvement, when the affected bowel wall becomes necrotic. Examination will, however, show rapid haemodynamic deterioration.

Colon torsions may produce the most violently painful and rapidly deteriorating group of patients. Cases with acute colitis (before breaking with diarrhoea) can mimic a colon torsion, especially when the bowel wall becomes infarcted. Both conditions may cause severe abdominal gas distention and thickened colon wall on abdominal ultrasound.

Haematology and serum biochemistry may assist in differentiation, as horses with acute colon torsion have normal haematology and albumin, while colitis cases are often neutropenic and hypoalbuminaemic.

Colitis cases may also have a fever and signs of toxaemia earlier in the disease process.

Medical colic management

The three pillars of successful medical colic management are:

- treatment of the underlying disease

- analgesia

- maintenance of homeostasis (including prevention of complications, such as hyperlipaemia and endotoxaemia)

Treatments may include enteral and/or IV fluids, analgesics and drugs, and procedures to prevent and manage complications such as laminitis and systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Common treatments

A comprehensive review of treatment for inflammatory and infectious gastrointestinal disorders is beyond the scope of this article, but the author will comment on a few aspects of common treatments.

- Some drugs in this article are used under the cascade.

References

- Hallowell GD (2008). Retrospective study assessing efficacy of treatment of large colonic impactions, Equine Vet J 40(4): 411-413.

- Lopes MA et al (2002). Treatments to promote colonic hydration: enteral fluid therapy versus intravenous fluid therapy and magnesium sulphate, Equine Vet J 34(5): 505-509.

- Lopes MA et al (2004). Effects of enteral and intravenous fluid therapy, magnesium sulfate, and sodium sulfate on colonic contents and feces in horses, Am J Vet Res 65(5): 695-704.

- Monreal L et al (2010). Enteral fluid therapy in 108 horses with large colon impactions and dorsal displacements, Vet Rec 166(9): 259-263.

- Hart KA et al (2013). Medical management of sand enteropathy in 62 horses, Equine Vet J 45(4): 465-469.

- Kendall A et al (2008). Radiographic parameters for diagnosing sand colic in horses, Acta Vet Scand 50(1): 17.

- Niinisto K et al (2014). Comparison of the effects of enteral psyllium, magnesium sulphate and their combination for removal of sand from the large colon of horses, Vet J 202(3): 608-611.

- Hotwagner K and Iben C (2008). Evacuation of sand from the equine intestine with mineral oil, with and without psyllium, J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr 92(1): 86-91.

- Freeman DE (2014). History of colic surgery and a look to the future, Proc 60th Ann Conv Am Assoc Eq Practit, Salt Lake City: 193-204.

- Hardy J et al (2000). Nephrosplenic entrapment in the horse: a retrospective study of 174 cases, Equine Vet J 32(S32): 95-97.

- McGovern KF et al (2012). Attempted medical management of suspected ascending colon displacement in horses, Vet Surg 41(3): 399-403.

- Hardy J et al (1994). Effect of phenylephrine on hemodynamics and splenic dimensions in horses, Am J Vet Res 55(11): 1,570-1,578.

- Frederick J et al (2010). Severe phenylephrine‑associated hemorrhage in five aged horses, J Am Vet Med Assoc 237(7): 830-834.

- Fleming K and Mueller PO (2011). Ileal impaction in 245 horses: 1995‑2007, Can Vet J 52(7): 759-763.

- Odelros E et al (2019). Idiopathic peritonitis in horses: a retrospective study of 130 cases in Sweden (2002-2017), Acta Vet Scand 61(1): 18.

- Fielding L (2014). Crystalloid and colloid therapy, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 30(2): 415-425.

- Gomaa N et al (2011). Effect of Buscopan compositum on the motility of the duodenum, cecum and left ventral colon in healthy conscious horses, Berl Munch Tierarztl Wochenschr 124(3-4): 168-174.

- Hart KA et al (2015). Effect of N-butylscopolammonium bromide on equine ileal smooth muscle activity in an ex vivo model, Equine Vet J 47(4): 450-455.

- de Lagarde M et al (2014). N-butylscopolammonium bromide causes fewer side effects than atropine when assessing bronchoconstriction reversibility in horses with heaves, Equine Vet J 46(4): 474-478.

- Sundra TM et al (2012). The influence of spasmolytic agents on heart rate variability and gastrointestinal motility in normal horses, Res Vet Sci 93(3): 1,426-1,433.

- Naylor RJ et al (2013). Comparison of flunixin meglumine and meloxicam for post operative management of horses with strangulating small intestinal lesions, Equine Vet J 46(4): 427-434.

- Lefebvre D et al (2014). Clinical features and management of equine post operative ileus: survey of diplomates of the European Colleges of Equine Internal Medicine (ECEIM) and Veterinary Surgeons (ECVS), Equine Vet J 48(2): 182-187.

- Hubbell JAE et al (2010). The use of sedatives, analgesic and anaesthetic drugs in the horse: an electronic survey of members of the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP), Equine Vet J 42(6): 487-493.

- Rusiecki KE et al (2008). Evaluation of continuous infusion of lidocaine on gastrointestinal tract function in normal horses, Vet Surg 37(6): 564-570.

- Doherty TJ (2009). Postoperative ileus: pathogenesis and treatment, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 25(2): 351-362.

- Malone E et al (2006). Intravenous continuous infusion of lidocaine for treatment of equine ileus, Vet Surg 35(1): 60-66.

- Torfs S et al (2009). Risk factors for equine postoperative ileus and effectiveness of prophylactic lidocaine, J Vet Intern Med 23(3): 606-611.

- Peiró JR et al (2010). Effects of lidocaine infusion during experimental endotoxemia in horses, J Vet Intern Med 24(4):940-948.

- Cook VL et al (2008). Attenuation of ischaemic injury in the equine jejunum by administration of systemic lidocaine, Equine Vet J 40(4): 353-357.

- Elfenbein JR et al (2014). Systemic and anti‑nociceptive effects of prolonged lidocaine, ketamine, and butorphanol infusions alone and in combination in healthy horses, BMC Vet Res 10(Suppl 1): S6.

- MacKay RJ et al (1999). Effect of a conjugate of polymyxin B-dextran 70 in horses with experimentally induced endotoxemia, Am J Vet Res 60(1): 68-75.

- Morresey PR and MacKay RJ (2006). Endotoxin-neutralizing activity of polymyxin B in blood after IV administration in horses, Am J Vet Res 67(4): 642-647.

- Sykes BW and Furr MO (2005). Equine endotoxaemia – a state‑of‑the‑art review of therapy, Aust Vet J 83(1-2): 45-50.

- Parviainen AK et al (2001). Evaluation of polymyxin B in an ex vivo model of endotoxemia in horses, Am J Vet Res 62(1): 72-76.

- Barton MH et al (2004). Polymyxin B protects horses against induced endotoxaemia in vivo, Equine Vet J 36(5): 397-401.

- Spier SJ et al (1989). Protection against clinical endotoxemia in horses by using plasma containing antibody to an Rc mutant E coli (J5), Circ Shock 28(3): 235-248.