14 Sept 2023

Equine worming protocols: advice to share with owners and yards

Jacqui Matthews BVMS, PhD, FRSB, FRSE, FRCVS, offers practical points for veterinarians to offer to clients, including anthelmintic resistance messages.

Gastrointestinal helminths – particularly cyathostomins – are ubiquitous in grazing horses.

Worms have limited clinical impact, as most horses harbour relatively low burdens; however, in a small number of susceptible individuals, elevated burdens can build up, which result in pathology and disease.

Horses – especially younger (less than five years old) and geriatric animals – are more likely to develop parasite-associated disease when control measures are absent, limited or ineffective.

Because of increasing drug resistance in several types of worm, it is important that sustainable approaches to control be applied. These focus on non-chemical (management) measures designed to reduce the force of worm infection in the environment, alongside the use of diagnostics that provide information to guide anthelmintic treatments to the most infected animals.

Such evidence-based protocols require thorough veterinary input so owners receive advice that is appropriate to the level of parasite risk.

Parasitic threats to horse health in the UK

The commonest helminths encountered in the UK are the cyathostomins (small redworms, small strongyles) and the equine tapeworm Anoplocephala perfoliata. Other prevalent species include the ascarid Parascaris species – a common infection of foals and weanlings – and the pinworm Oxyuris equi, occasionally found as a persistent issue on some yards.

Cyathostomins and Parascaris species are particular threats because both are adept at developing anthelmintic resistance (Matthews, 2014; Nielsen, 2022). In the past, the large strongyle, Strongylus vulgaris, was detected at high prevalence in the UK and was a serious threat due to its potential pathogenicity.

However, S vulgaris is now rarely reported in the UK due to long-term, regular use of ivermectin and moxidectin, and, so far, anthelmintic resistance has not been observed in this species.

Nevertheless, this nematode should be considered as a re-emergent risk in horses that receive negligible anthelmintic treatments over extended periods.

Anthelmintic resistance

Anthelmintic resistance is increasingly compromising effective equine helminth control. No new anthelmintic classes have been introduced for more than 40 years and, across the world, many cyathostomin populations have been reported as resistant to benzimidazole and tetrahydropyrimidine (pyrantel salt) class anthelmintics (Nielsen, 2022), with recent reports of resistance to the macrocyclic lactones, including in the UK (Bull et al, 2023).

Numerous reports have also emerged of reduced cyathostomin egg reappearance periods after moxidectin and ivermectin treatment – an indicator of emerging resistance (Matthews, 2014; Nielsen, 2022). Of further concern are recent reports of resistance to the fenbendazole larvicidal protocol and the view that the larvicidal effect of moxidectin is variable (Bellaw et al, 2018; Nielsen, 2022).

Parascaris equorum resistance to macrocyclic lactones is a major issue on breeding farms (Raza et al, 2019). Recent reports also suggest that P equorum resistance to the other anthelmintic classes is an emerging concern, while ivermectin and moxidectin resistance in O equi has been reported across all four continents (Nielsen, 2022).

Factors that drive anthelmintic resistance include the following:

- high treatment frequency

- treating all horses at the same time and, therefore, not protecting some of the host worm population from anthelmintic exposure

- treating horses when environmental conditions favour low levels of worms on pasture (“refugia”) – this reduces any dilution effect when progeny of worms that survive anthelmintic treatment are shed on to pasture

- under-dosing with anthelmintic, which promotes survival of partially resistant genotypes

- treating horses, then moving them immediately to clean pastures (“dose and move”)

Because no new classes are near to market, control programmes that avoid these practices need to be applied to protect the remaining efficacy of the anthelmintics currently available.

It is important to ensure clients are aware of this to drive change in practice – particularly as some resistance-promoting practices (such as “dose and move”) might have been recommended previously by experts.

Worm control strategies that aim to preserve anthelmintic efficacy

To reduce selection pressure for resistance, evidence-based approaches to control need to be applied, while being cognisant of the requirement to avoid pathogenic burdens in worm-susceptible individuals.

Because of the range of management systems encountered, no one size fits all approach exists and veterinarians need to obtain an understanding of on-site management (Panel 1) so they can design worm control plans appropriate to the level of risk of transmission and infection.

- The number of horses at the premises and how they are grouped on grazing

- Group stocking density

- The age profile of the grazing groups

- The grazing pattern – year round, grazing time per day

- Supplementation of grazing and how this pattern varies with season

- If dung removal is practised, and if so, frequency of removal across seasons

- Approach to resting pastures and cross grazing with other species

The next step of the process is to develop an understanding of the background to parasite management at the premises (Panel 2).

What sort of worm control programme has been applied previously: no formal programme, interval treatment programme, diagnostics-led targeted treatment programme?

If the latter, what were the results of tests applied?

Which anthelmintics have been used and how frequently were these administered?

Has resistance testing been undertaken and if so, what were the results?

Does a history of gastrointestinal disease exist that might be associated with the presence of high parasite burdens?

Answers to these questions will help enable an understanding of the parasites likely to be present and the level of exposure. The information can then be used to recommend management procedures to reduce parasite transmission from pasture and a testing plan, delivered at a frequency relevant to the transmission risk identified.

Diagnostics tests are performed to provide information on the following:

- which types of parasites are present

- the prevalence of these across the grazing population

- the levels of infection in the population and how it is distributed among individuals

- worm sensitivity to the anthelmintics used

Owners need to understand that individual animals vary considerably in their ability to control helminths – particularly in adult horse populations where a small proportion (less than 20%) of the group is likely to excrete the majority (more than 80%) of strongyle eggs on to pasture (the negative binomial distribution).

Until animals are assessed by faecal egg count (FEC) and other tests, it is unknown which individuals fall within different egg shedding or worm burden categories, respectively.

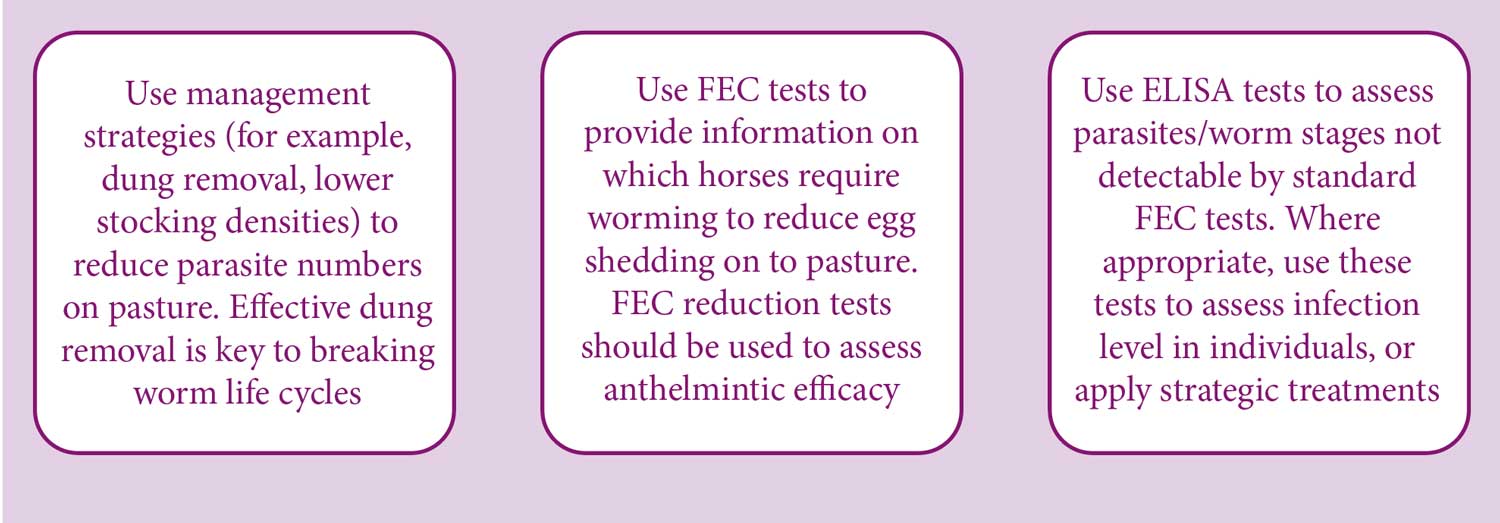

Sharing the principles of what is known about worm distributions within equine populations will help encourage owners/yard managers to include all animals in their control planning; sometimes, a key challenge on multi-owner livery yards or where considerable numbers of horses are present (for example, on large breeding operations). Using the information garnered from the questions previously mentioned, a helminth control plan can then be designed based on the principles in Figure 1.

Control plans must emphasise management measures – the purpose of which are to reduce parasites on pasture. Successful application of these will lower the burden in grazing horses and, if applied with appropriate diagnostics, will lead to substantial reductions in anthelmintic usage, which should reduce selection pressure for resistance while avoiding pathogenic burdens.

Non-chemical practices to reduce parasite transmission in the environment are shown in Figure 2.

Engaging owners in improving pasture hygiene is key to effective control; however, it can be challenging to convince them to commit to these practices – especially where many horses are present with different owners, with some considering these to involve too much physical effort.

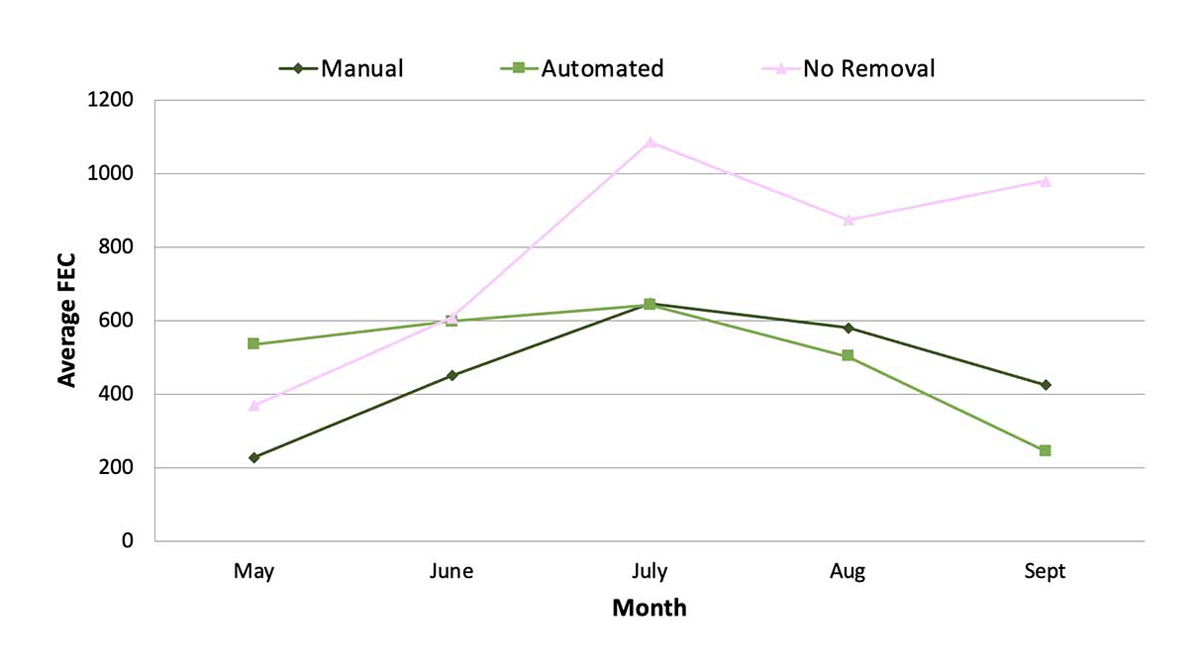

To be effective, dung removal needs to be performed frequently enough to prevent infective larvae moving from faecal pats on to grass. In UK summer conditions, deposited strongyle eggs can reach infective third-stage larvae (L3) in less than a week (Figure 3).

Herd (1986) demonstrated that lifting dung from pasture twice a week afforded significant reductions in parasite infectivity, reducing reinfection potential for grazing horses.

In these studies, removing dung at this frequency led to a maximum contamination level of only 1,000 strongyle L3/kg herbage compared to 18,486 L3/kg herbage observed on pastures where dung was not removed. In these studies, dung removal was also found to increase the effective grazing area by approximately 50% by reducing the level of separation of pasture into “roughs” and “lawns”.

Group engagement (such as practice talks) and sharing of accessible written materials could help encourage implementation, or veterinarians could drive a top-down approach by working with the yard manager to formulate rules relating to parasite control.

Studies have shown that merely making owners aware of the threat of resistance is insufficient to drive change in practice; however, using real metrics to demonstrate the value of implementing better management approaches seems to improve uptake (Vineer et al, 2017).

For example, consider using yard FEC results over time to demonstrate the positive effect of dung removal. Figure 4 provides an example of how dung removal measures affected donkey FEC in a multi-paddock study at The Donkey Sanctuary, UK.

FEC tests are the foundation of evidence-based control programmes

FEC tests are invaluable in assessing the parasite type(s) present (for example, strongyle eggs; Figure 5) and how egg excretion is distributed among horses. FEC tests, therefore, provide key information on which horses to target anthelmintic treatments to reduce egg shedding.

Note that FEC tests do not correlate linearly with adult worm burdens, nor do they provide information on immature stages such as cyathostomin encysted larvae. Standard methods used in most laboratories do not have good sensitivity for tapeworm eggs, nor do they detect O equi eggs that adhere to skin in egg packets; these are detectable using a tape test.

From spring to late summer, FEC tests should be performed every 8 to 12 weeks, depending on the anthelmintic used. The entire grazing group should be tested to understand which individuals are moderate/high shedders (excreting more than 200 eggs per gram [EPG] of faeces) and which are negative/low shedders (zero to less than 200 EPG).

In managed populations, many horses will be under the 200 EPG threshold, so the number of treatments administered should be greatly reduced compared to applying a blanket treatment protocol. If many adult horses are above the 200 EPG threshold, this should flag concern that control measures are not working effectively and pasture hygiene needs to be improved. High levels of worm egg shedding may also be a red flag for possible resistance to the products being administered and an efficacy test should be performed.

Note that younger animals (less than five years) tend to have higher FECs than adult horses and FEC monitoring of these groups may need to be performed at higher frequency.

Where stocking density is low, grazing extensive and/or where dung removal is performed every day, and if less than 20% of horses are excreting strongyle eggs at less than 200 EPG, consider raising the treatment threshold to 500 EPG to further reduce anthelmintic use.

One should consider using FEC tests in horses that graze all day in winter – especially in mild years where egg to larval development may be possible. FEC tests performed during this season will provide information on the length of time larvicidal treatments suppress egg excretion. If treated with moxidectin, it is recommended to test a minimum of 10 weeks after treatment.

It is key to get owners to understand that testing anthelmintic effectiveness is an essential part of worm control planning. Surveys have shown low uptake of efficacy testing in the field, despite the fact that respondents in such surveys state a high level of awareness of the threat of resistance (Relf et al, 2012; Walshe et al, 2023).

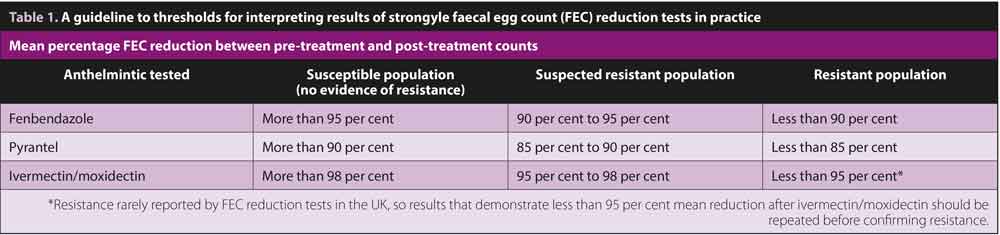

If sufficient numbers of horses (six or more) are excreting strongyle eggs at a level of more than 200 EPG, a FEC reduction test can be performed by FEC testing as near as possible to the time treatment (ideally, on the same day) and again 14 days later.

At this point, calculation of the mean percentage reduction in FEC for the group provides information on the effectiveness of the anthelmintic administered. Table 1 provides a simple guide to assessing whether resistance is present in the population being tested.

Before reporting resistance, reduced efficacy should be observed in most, if not all horses. If the mean FEC reduction value is near the thresholds indicated in Table 1, the test should be repeated before confirming resistance. If less than six horses are assessed, the outcome is likely to be less accurate due to variation in FEC between individuals.

Other tests to use in evidence-based control programmes

Some tests help identify parasite species or stages not detected by standard FEC analysis, and include antibody-based tests for Anoplocephala perfoliata and cyathostomins.

Antibody-based tapeworm tests

Eggs of Anoplocephala species are not readily detected using standard FEC methods. Modified coprological methods can be used to increase sensitivity, but these require large volumes (30g to 40g faeces) and, usually, access to centrifuges (Andersen et al, 2013).

Measurement of antibodies to A perfoliata antigens provides an accurate, user-friendly method to detect infection. Owners can choose between serum or saliva testing – the latter performed by the owner using a kit provided by the practice with results reported to the veterinarian for interpretation.

These tests measure worm-specific IgG(T) – levels of which show strong positive correlations with infection intensity (Proudman and Trees, 1996; Lightbody et al, 2016). Serum and saliva tests incorporate a calibration curve format in each test to generate a precise “score”. Scores are classified as “low”, “borderline” or “moderate/high”, with anti-cestode treatment recommended when results report the latter two categories.

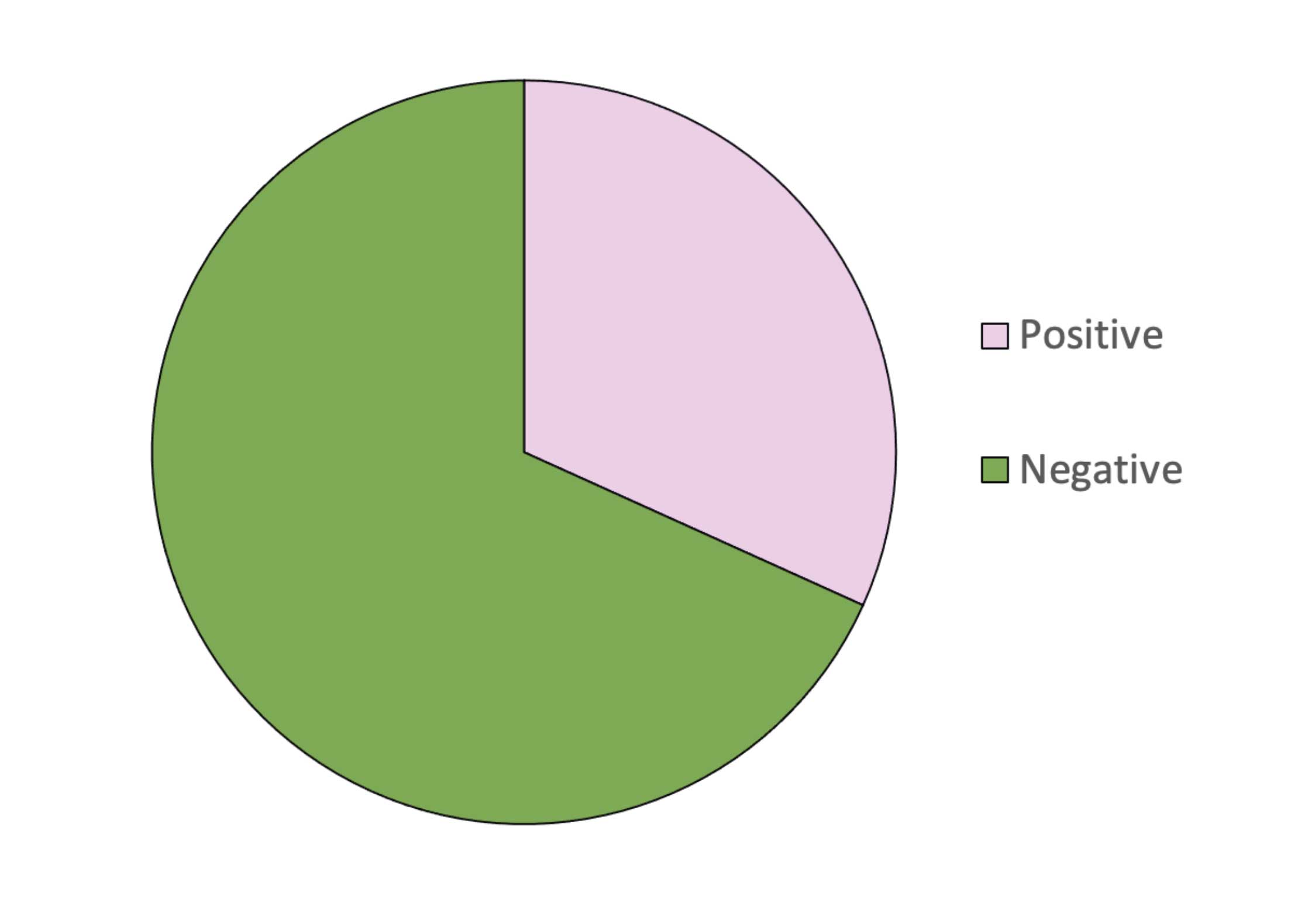

The saliva test is used considerably more that serum testing in the UK and, since 2015, its application has afforded considerable reductions in anthelmintic use (Figure 6). Based on results held in Austin Davis Biologics’ database, of 164,002 tests run, approximately 68% of horses reported as “low” (negative in terms of “advise to treat”), saving 111,931 anti-cestode treatments compared to interval worming.

Although higher tapeworm burdens have been observed in some studies in autumn, a clear seasonal trend in transmission does not appear to exist.

A recent Danish study (based on more than 11,000 coprological test observations) demonstrated no clear seasonality of egg detection, despite a higher prevalence in autumn, and that egg-producing Anoplocephala species were found year-round (Engell-Sørensen et al, 2018). The study found no significant difference in infection across regions, indicating lack of association between prevalence and soil type.

The study identified, in a subset of 1,200 horses, that prevalence was higher in one to five year olds. Frequency of testing should, therefore, be based on assessment of infection risk.

Horses grazing pasture where previous tests demonstrate higher burdens, or where tapeworm-related disease has occurred, or groups with high proportions of younger animals, should be tested spring and autumn. Horses considered at lower risk (where previous tests indicate no/low levels of infection, no previous history of tapeworm-related disease or most animals are older than five years of age) should be considered for testing annually, in spring or autumn.

Anthelmintics licensed for treatment of tapeworm have a short half-life, reaching negligible levels in approximately 24 hours, after which horses are rapidly reinfected if grazing contaminated paddocks.

Therefore, it is important to ensure that re-infection risk is reduced by good pasture management.

In horses that report with a borderline or moderate/high result, a re-test can be performed 10 to 12 weeks after treatment. This is because worm-specific IgG(T) reduces more quickly in saliva than in serum, with studies indicating that in more than 70% of praziquantel-treated horses, saliva IgG(T) reduces to below treatment threshold levels within five weeks (Lightbody et al, 2016).

If antibodies are high at a re-test from this point, ongoing transmission should be deemed an issue. Discussion with the client should consider if another treatment should be administered to mitigate further contamination – especially if it seems that improving pasture management would be problematic.

All co-grazing horses should also be tested in case they are a contamination source; this can be challenging on multi-owner livery yards. Working with the yard manager and educating all owners on the importance of group testing could improve compliance.

Antibody-based cyathostomin test

Strongyle FECs do not show a linear correlation adult worm burdens, nor do they provide any information on the levels of host infection with immature larvae.

For many years, owners have been advised to treat horses in autumn with anthelmintics licensed to kill cyathostomin mucosal and adult stages in autumn or winter. This is based on timing applications to reduce the impact of such treatments on pasture refugia; in autumn, pasture contamination is considered to be highest (Nielsen et al, 2007) and when mucosal larval stages have been identified at higher abundance (Ogbourne, 1972).

Instead of administering autumn/winter “larvicidal” treatments to all horses, the Small Redworm Test (Austin Davis Biologics) can be used in horses considered at low risk of infection to assess if they require treatment based on serum IgG(T) levels to cyathostomin specific proteins (Tzelos et al, 2020; Lightbody et al, under review).

Similar to the tapeworm tests, the Small Redworm Test includes a calibration curve format which generates a “serum score” for each horse.

At a serum score threshold of 14.37 (1,000 total cyathostomin burden threshold), this test performs at 97.65% sensitivity and 85.19% specificity, and at a serum score threshold of 30.46 (10,000 total cyathostomin burden threshold), a sensitivity of 91.55% and specificity of 75.61%.

Horses suitable for testing are those that return low (that is, less than 200 EPG) FEC results in recent tests and graze pasture where regular (at least once a week) dung removal occurs. The test results are interpreted by veterinarians to inform decisions on cyathostomin treatments in autumn/winter.

Depending on transmission risks within a herd, observations in naturally infected populations indicate that use of the Small Redworm Test can lead to reductions in treatments of 20% (in high transmission settings) to 78% (in low transmission settings).

Conclusions

Adoption of best practice control requires horse owners to make complex risk assessments and evaluate how these can be integrated within the restrictions of their own environment, resources and management systems (Vineer et al, 2017).

As non-experts, owners have to evaluate risk based on incomplete knowledge of equine health, parasitology and scientific evidence; this is where veterinarians can work to bridge the gap in knowledge, to encourage owners to implement the elements of best practice adapted to their particular conditions and capabilities.

To encourage uptake, veterinarians need to support owners in how to understand parasite disease risk and explain the options available to reduce risk of infection for the horses in their care.

In the UK, horses are often kept on liveries with several owners and where the worming strategy of one directly affects the health of others. In these cases, yard managers or advocates of evidence-based methods of control should be involved to encourage more widespread use through peer influence.

Do not underestimate the importance of education and awareness in empowering behaviour change; even small increases in perceived knowledge by owners could be beneficial to encourage sustainable control practices (Vineer et al, 2017). Knowledge transfer activities, such as practice talks and sharing of tools that provide basic information of evidence-based control, could enhance uptake by improving self-efficacy and perceived control (Vineer et al, 2017).

A newly established cross-sector working group, Controlling ANTiparasitic resistance in Equines Responsibly (canterforhorses.org.uk), has been formed to emphasise the significance of a strategic approaches to managing worms in horses.

The initiative comprises veterinarians, SQPs, industry organisations, policy makers, pharmaceutical companies, horse owners and charitable organisations, and is generating tools that can used by veterinarians to support them in discussing risk assessment and parasite control options with their clients.

References

- Andersen UV, Howe DK, Olsen SN and Nielsen MK (2013). Recent advances in diagnosing pathogenic equine gastrointestinal helminths: The challenge of prepatent detection, Vet Parasitol 192(1-3):1-9.

- Bellaw JL, Krebs K, Reinemeyer CR, Norris JK, Scare JA, Pagano S, Nielsen MK (2018). Anthelmintic therapy of equine cyathostomin nematodes – larvicidal efficacy, egg reappearance period, and drug resistance, Int J Parasitol 48(2): 97-105.

- Bull KE, Allen KJ, Hodgkinson JE and Peachey LE (2023). The first report of macrocyclic lactone resistant cyathostomins in the UK, Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 21: 125-130.

- Corbett CJ, Love S, Moore A, Burden FA, Matthews JB and Denwood MJ (2014). The effectiveness of faecal removal methods of pasture management to control the cyathostomin burden of donkeys, Parasit Vectors 7: 48.

- Engell-Sørensen K, Pall A, Damgaard C and Holmstrup M (2018). Seasonal variation in the prevalence of equine tapeworms using coprological diagnosis during a seven-year period in Denmark, Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports, 12: 22-25.

- Herd RP (1986). Epidemiology and control of equine strongylosis at Newmarket, Equine Vet J 18(6): 447-452.

- Lightbody KL, Davis PJ and Austin CJ (2016). Validation of a novel saliva-based ELISA test for diagnosing tapeworm burden in horses, Vet Clin Pathol 45(2): 335-346.

- Matthews JB (2014). Anthelmintic resistance in equine nematodes, Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 4(3): 310-315.

- Matthews JB et al (2023). Unpublished data, Austin Davis Biologics commercial database.

- Nielsen MK, Kaplan RM, Thamsborg SM, Monrad J and Olsen SN (2007). Climatic influences on development and survival of free-living stages of equine strongyles: implications for worm control strategies and managing anthelmintic resistance, Vet J 174(1): 23-32.

- Nielsen MK (2022). Anthelmintic resistance in equine nematodes: current status and emerging trends, Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 20: 76-88.

- Ogbourne CP (1972). Observations on the free-living stages of strongylid nematodes of horses, Parasitology 64(3): 461-477.

- Proudman CJ and Trees AJ (1996). Correlation of antigen specific IgG and IgG(T) responses with Anoplocephala perfoliata infection intensity in the horse, Parasite Immunol 18(10): 499-506.

- Raza A, Qamar AG, Hayat K, Ashraf S and Williams AR (2019). Anthelmintic resistance and novel control options in equine gastrointestinal nematodes, Parasitology 146(4): 425-437.

- Relf VE, Morgan ER, Hodgkinson JE and Matthews JB (2012). A questionnaire study on parasite control practices on UK breeding Thoroughbred studs, Equine Vet J 44(4): 466-471.

- Tzelos T, Geyer KK, Mitchell MC, McWilliam HEG, Kharchenko VO, Burgess STG and Matthews JB (2020.) Characterisation of serum IgG(T) responses to potential diagnostic antigens for equine cyathostomins, Int J Parasitol 50(4): 289-298.

- Vineer HR, Velde FV, Bull K, Claerebout E and Morgan ER (2017). Attitudes towards worm egg counts and targeted selective treatment against equine cyathostomins, Prev Vet Med 144: 66-74.

- Walshe N, Burrell A, Kenny U, Mulcahy G, Duggan V and Regan A (2023). A qualitative study of perceived barriers and facilitators to sustainable parasite control on thoroughbred studs in Ireland, Vet Parasitol 317: 109904.