25 Feb 2025

Evolution of the UK’s equine infectious disease surveillance

Fleur Whitlock BVetMed(Hons), MSc, MRCVS, Abbi McGlennon BSc(Hons), PhD and Richard Newton BVSc, MSc, PhD, FRCVS answer the question of “why we watch” for trends of infectious respiratory illnesses in horses, highlighting the essential work of organisations monitoring across the country

Image © vprotastchik/ Adobe Stock.

The rising emergence of infectious diseases – driven by pathogen adaptation, climate change expanding the range of disease vectors, and the growing national and international movement of horses – highlights the critical need for robust surveillance.

In equine populations, such systems are vital for safeguarding horse health and welfare while ensuring the sustainability and resilience of the equine industry.

This article, the first in a two-part series, will explore how surveillance of equine infectious disease in the UK has developed and evolved over time in response to various disease scenarios and industry needs.

The second part will focus on how surveillance outputs are communicated with stakeholders, the future advancements needed to address the evolving disease landscape and the challenges facing surveillance.

Evolution of surveillance of equine infectious diseases in the UK

Dedicated diagnosis, surveillance and research of equine infectious diseases in the UK was conducted for more than 40 years at the Animal Health Trust (AHT) in Newmarket, with sustained funding coming from the Thoroughbred racing and breeding industry. An AHT group dedicated to surveillance and assisting industry with the prevention and control of disease outbreaks transitioned to the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Cambridge in 2021 following the closure of the AHT in 2020, continuing its work as Equine Infectious Disease Surveillance (EIDS).

Over time, the surveillance systems managed by the EIDS group have evolved in response to emerging threats, technological advancements and new opportunities.

In the 1960s, major outbreaks of equine influenza (EI) in Great Britain prompted the introduction of influenza vaccines by around the middle of the decade. While the vaccines proved effective, influenza outbreaks continued to occur sporadically and, following a large-scale EI outbreak in 1979, vaccination was made mandatory in racehorses in 1981.

The establishment of the Equine Virology Unit at the AHT in 1980 under Jenny Mumford, in response to EI and significant equine herpesvirus-1 (EHV-1) outbreaks, marked a pivotal development in the UK’s approach to managing equine infectious diseases. The unit focused on improving diagnostic methods for early and accurate detection of infectious disease occurrence, monitoring disease spread, and conducting research to optimise control and prevention strategies, such as vaccination. This multidisciplinary approach, developed and broadened over several decades, integrated veterinary surgeons and scientists, and utilised both in vitro and in vivo methods supported by access to evolving molecular technologies.

As it developed, the AHT Equine Virology Unit transitioned into the Department of Infectious Diseases in 1984 and the Centre for Preventive Medicine in 1995. During this time, the group under Dr Mumford became a leader in international collaboration, establishing formal, annual exchanges of laboratory and surveillance data by a panel of experts, under the auspices of the Office International des Epizooties (now the World Organisation for Animal Health), which reviewed and periodically recommended when EI vaccine virus strains needed updating. The development of surveillance and vaccination strategies has significantly reduced the frequency and severity of EI outbreaks in the UK, and ongoing research and adaptation of control measures remain vital in addressing emerging strains of the virus.

EIDS, alongside virologists and scientists in the Equine Virology Group – also funded by the equine industry and now based at the University of Cambridge – continues to build on its strong surveillance foundation, supporting the equine industry in optimising control and prevention strategies for infectious diseases in an increasingly changing and challenging landscape.

Current surveillance methods used

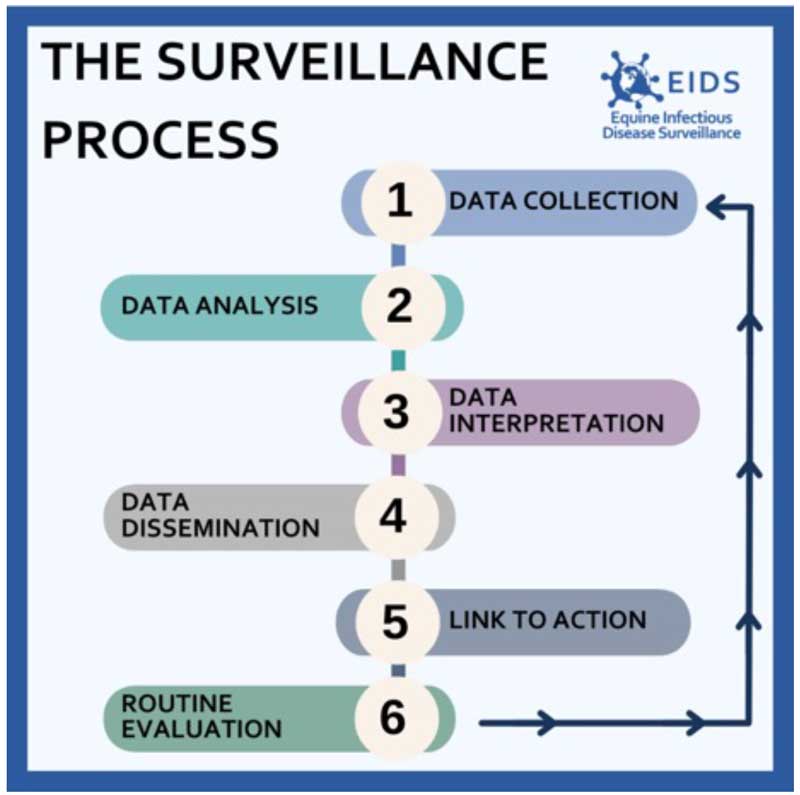

Infectious disease surveillance is the continuous, systematic collection, analysis and interpretation of disease-related data, with dissemination of findings and, where necessary, taking appropriate action and conducting routine evaluation (Figure 1). Its applications are tailored to specific goals, such as:

- Detecting increased disease activity against endemic backgrounds to prompt interventions such as vaccination or awareness initiatives.

- Identifying populations for targeted prevention or control efforts.

- Estimating disease magnitude, impact and transmission potential.

- Assessing prevention and control programme success.

- Recognising exotic or novel diseases for rapid response.

- Stimulating research to advance disease prevention and improve population health.

Surveillance systems are designed based on disease risk, epidemiology and available resources, drawing from a variety of data sources.

Diagnostic laboratory data

A completely retrospective surveillance approach is evidenced by the Equine Quarterly Disease Surveillance Report (EQDSR), produced in collaboration with the APHA and BEVA.

The EQDSR includes a laboratory surveillance section that compiles data on the number of samples tested and the number of positives for each reported diagnostic test, including the number of laboratories contributing the data for each test. Although the EQDSR relies on retrospective data, it draws information from approximately 30 commercial laboratories conducting diagnostic testing across the UK.

This long-standing surveillance and reporting system has been in operation for more than 20 years, providing a robust dataset that offers valuable insights into disease trends, testing patterns and the epidemiology of equine infectious diseases within the UK.

A recent analysis of EQDSR data (accepted for publication) examined faecal worm egg count testing trends from 2007 to 2023. The findings highlight EQDSR’s role in monitoring resistance and guiding equine health strategies, reinforcing the importance of retrospective surveillance. A more recent laboratory surveillance initiative involves EIDS collaborating with the VMD as part of the broader, multispecies National Biosurveillance Network, to develop a surveillance system for equine antimicrobial resistance.

In the early phase of this project, EIDS is focused on developing the scheme’s requirements and methods, with plans to reach out to laboratories to encourage their collaboration once the framework is established. This initiative aims to enhance the monitoring and understanding of antimicrobial resistance within the equine population, ultimately benefiting the health of all species by promoting responsible antimicrobial use and reducing resistance.

Sentinel case/outbreak surveillance

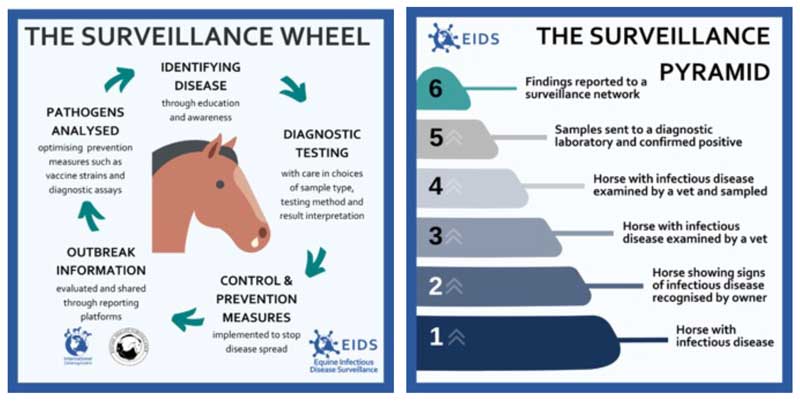

The primary real-time surveillance method to identify, monitor and control disease occurrences in the UK is through a pathway referred to as the “surveillance wheel” (Figure 2a). This approach relies heavily on the initial recognition of potential disease manifestations by horse owners or keepers, and subsequent veterinary involvement and diagnostic testing. Conventionally, this surveillance method focuses on laboratory-confirmed cases, and this reliance on laboratory-based data is recognised to have limitations, as significant information may be lost due to under-reporting or failure to submit samples for testing (Figure 2b).

To aid the successful turning of the surveillance wheel, EIDS oversees a network of collaborating laboratories across the UK. Upon confirmation of a positive sample, with current focus on EI and EHV-1/EHV-4, laboratories are encouraged to alert EIDS that a positive sample has been confirmed and also to contact the referring veterinary surgeon to encourage engagement with EIDS’ surveillance system.

EIDS can provide free outbreak management advice while also facilitating the collection of epidemiological case/outbreak data, alongside sample contribution for virus isolation and further molecular analysis and characterisation. These initiatives are critical for timely outbreak detection, informing control measures and enhancing the broader understanding of disease dynamics within equine populations.

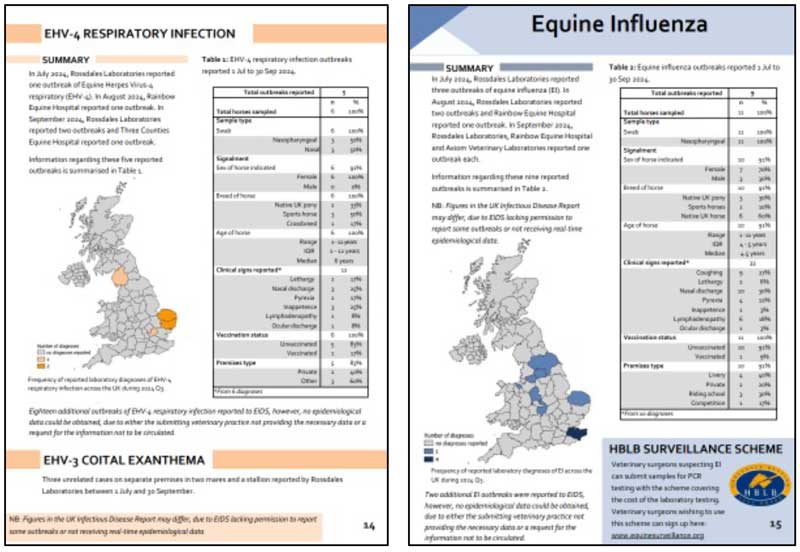

Recent outbreaks of EHV and EI that have been notified through this collaborating laboratory surveillance network, providing where requested opportunities for outbreak assistance from EIDS to optimise outbreak control and clearance, to limit onward spread, raise awareness and occasionally for education purposes, are shown in Figure 3, which were summarised in the EQDSR for Q3 2024.

EIDS has launched a new online platform to streamline the process for veterinary surgeons to share case and outbreak epidemiological data. Previously, this information was collected using a static outbreak information form attached to an email, which required manual handling – either being printed, filled in by hand, scanned and reattached, or completed electronically via a fillable PDF document and re-emailed.

The new system eliminates these inefficiencies, allowing case data to be directly entered into an online webform, with the data held in a secure, encrypted cloud database, protected by virtual private network access and password authentication. This innovation not only improves data accuracy and timeliness, but also simplifies the reporting process for veterinary professionals.

Enhanced surveillance

EIDS, in collaboration with virologists from the Equine Virology Group, oversees the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB)-funded Equine Influenza Surveillance Scheme.

This scheme enables participating veterinary surgeons to submit nasopharyngeal swabs taken from horses exhibiting clinical signs suggestive of EI (regardless of vaccination status) for free PCR testing. Upon positive confirmation, anonymised epidemiological data are collected and shared through EIDS’ reporting platforms.

As well as through the HBLB-subsidised flu testing scheme, positive influenza samples are also identified and reported via EIDS’ wider viral outbreak surveillance, which is conducted in conjunction with members of EIDS’ collaborative laboratory network, thereby ensuring as comprehensive monitoring and reporting as possible. This outbreak surveillance provides the information for real-time alerts on influenza for industry through the International Collating Centre and TellTail text message alert service, with the latter supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health.

Virus-positive samples are submitted via an industry-supported viral isolate library based at Rossdales Laboratories in Newmarket. Influenza positive samples are quickly forwarded to the Equine Virology Group at Cambridge to undergo virus isolation and whole genome sequencing in near real time, wherever possible, providing valuable insights into viral evolution, vaccine performance and transmission dynamics. This type of enhanced surveillance proved critical in 2019 when it identified that more EI outbreaks had been confirmed in the first week of January that year than during the entirety of the previous year. This early detection allowed EIDS to raise awareness across the equine industry and prompted the implementation of six-monthly booster vaccinations for racing Thoroughbreds. Molecular analysis of the isolates further revealed that the H3N8 viral strain was a novel introduction to the UK, belonging to the Florida Clade 1 (FC1) lineage.

This demonstrated that commercially available vaccines should impart a level of protection to this circulating strain, and indeed did so in populations where vaccines were utilised optimally, heeding the advice to shorten booster intervals to 6 months rather than 12 months.

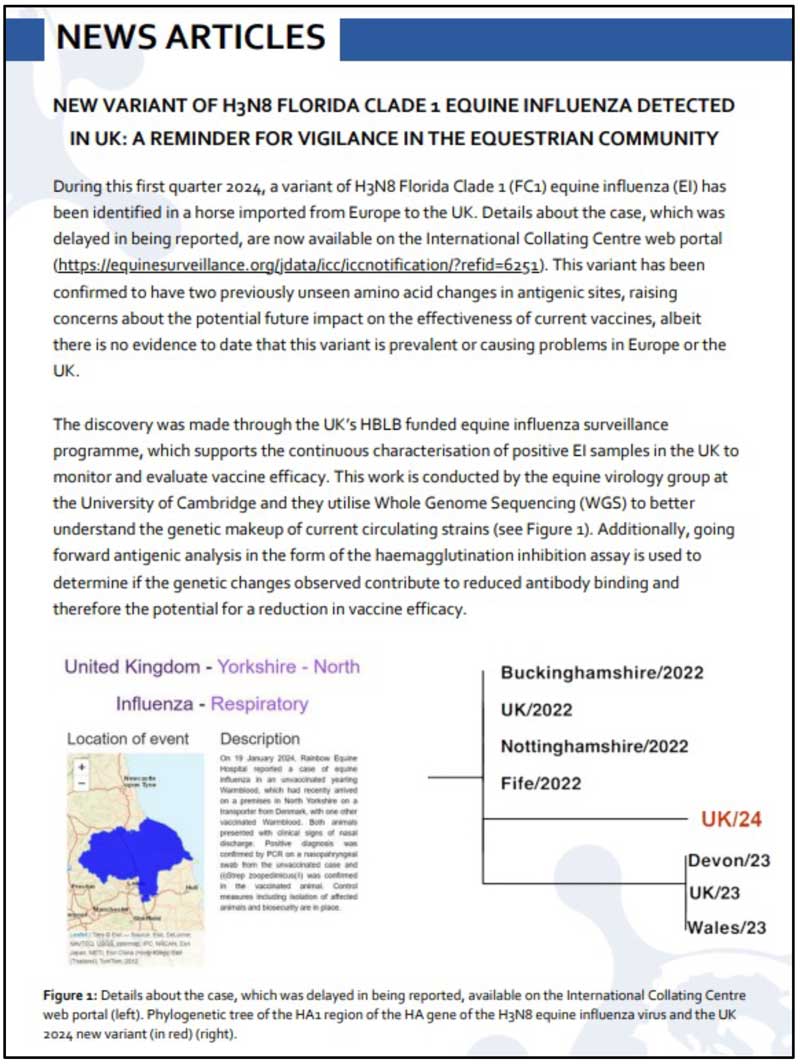

In the first quarter of 2024, enhanced surveillance identified a variant of H3N8 FC1 in a horse imported from Europe to the UK, featuring two previously unseen amino acid changes in antigenic sites. While this raised some initial concern about the potential impact on current vaccine effectiveness, no evidence to date suggests that the variant is prevalent or causing significant issues in Europe, or the UK.

Awareness efforts included news updates emphasising vigilance and biosecurity measures, such as continuing with six-monthly booster vaccinations, ensuring new arrivals are fully vaccinated before travel, and prompt investigation and management of horses displaying clinical signs (Figure 4).

EIDS also manages the Surveillance of Equine Strangles (SES) network, which, similar to influenza surveillance, collects epidemiological data from clinical cases across the UK and, up until the end of 2022, also collected bacterial isolates. Whole genome sequencing of Streptococcus equi isolates recovered from horses across the UK via the SES network between 2016 and 2022 shed new light on the endemic persistence of strangles in the UK. More than 500 samples contributed to the analysis, with results indicating a much quicker change in the predominant group of S equi strains circulating among horses in the UK than previously expected.

The observed speed of changes in circulating strains suggests that acute infection, or recently convalesced subclinical horses returning to normal activity on the assumption that they are clear of infection, may be larger drivers of strangles transmission and endemicity in the UK than previously thought.

Furthermore, transmission analysis combining the epidemiological and whole genome sequencing data of S equi strains across the same time period confirmed that closely related genetic strains of S equi are transmitting across the UK over short periods of time. For example, an onward transmission chain was identified within a six-month period among nine sampled horses across all four countries of the UK, with direct transmission events identified between five horses.

Through this work, we were able to conclude that transmission of genetically related strains between diverse UK regions suggests that the movement of horses across the UK facilitates S equi transmission. To stay informed of laboratory diagnoses of strangles across the UK, SES has a dashboard updating in near real time: tinyurl.com/EIDSstrangleshub

Serological surveillance

Monitoring antibodies against pathogens is a simple and convenient method for conducting surveillance, although complications inevitably exist where vaccines are used to induce protective antibodies, but where vaccine technology prevents the ability to serologically differentiate infected from vaccinated animals (so-called DIVA capability). However, a recent example exists where serological surveillance has been helpful in the context of the non-availability of a non-DIVA equine vaccine, in confirming ongoing absence of a notifiable equine infectious disease, where seropositivity in lapsed vaccinated horses by law requires virological investigation.

The Equip Artervac equine viral arteritis vaccine effectively went off the market in late March 2023 when it reached its expiry date; since then, Zoetis, Artervac’s manufacturer, has notified on several occasions that its return to market has been delayed. Having been notified of the impending non-availability of Artervac in late 2022, and to avoid the need for seropositive lapsed vaccinated stallions to undergo semen collection for virus testing, the Thoroughbred breeding industry, advised by EIDS, developed a serological surveillance scheme for clearing stallions.

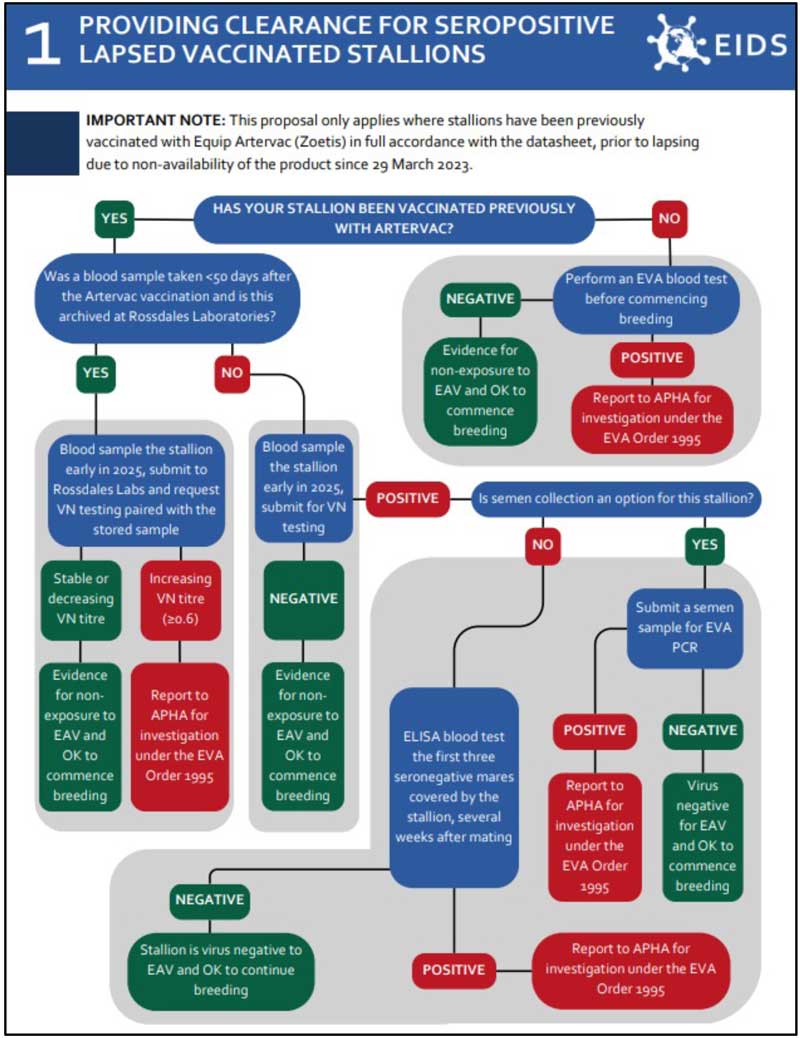

A decision tree to determine the appropriate course of action and associated laboratory tests to be applied to lapsed vaccinated stallions and teasers was designed (Figure 5). The rationale behind the decisions, which Defra was happy to endorse, was as follows:

- Less frequently vaccinated stallions may have reverted to a seronegative status when tested serologically and would be considered free from equine arteritis virus (EAV) and will require no further action.

- Well-vaccinated stallions would be expected to remain seropositive for a prolonged period after the last Artervac vaccine dose and would need to demonstrate freedom from EAV exposure and/or viral shedding.

- Some, mainly Thoroughbred stallions, have serum samples stored that were taken several weeks after the last dose of Artervac was administered as per the previous advice. These samples would have coincided with likely peak vaccination antibody levels, which in the absence of infectious challenge with EAV during the intervening period would be expected to decline or remain stable with time since vaccination (that is, no seroconversion would be evident). Absence of seroconversion on virus neutralisation antibody testing of these samples, paired with routine pre-breeding samples taken early in the year, would provide evidence for non-exposure to EAV.

Conclusion

The evolution of equine infectious disease surveillance in the UK reflects decades of collaboration, innovation and adaptation in response to emerging threats and industry needs.

From the foundational work at the AHT to the current initiatives led by EIDS, the development of diagnostic capabilities, sentinel surveillance and laboratory networks has significantly enhanced the equine sector’s ability to detect, manage and prevent outbreaks.

This historical and ongoing commitment to surveillance has not only protected horse health, but also supported the sustainability of the broader equine industry. The integration of real-time outbreak reporting, retrospective laboratory data collection and emerging technologies highlights the multifaceted approach necessary to tackle infectious diseases in a dynamic environment.

However, as the landscape of infectious disease continues to evolve, surveillance systems must continue to adapt.

In part 2 of this series, the authors will delve deeper into the communication of surveillance outputs, exploring how information is shared with stakeholders, including vets, horse owners and policymakers. They will also examine the future directions for equine disease surveillance in the UK, addressing technological advancements, the importance of stakeholder engagement and the critical challenges that lie ahead. This will ensure that the equine industry can remain resilient and proactive in the face of emerging disease threats, ensuring the continued health and welfare of horses across the nation.

To learn more about EIDS, contribute to, and sign up for the various surveillance schemes available, visit https://equinesurveillance.org