15 Jan 2021

Emily Haggett reviews a general approach to the horse with suspected intestinal disease, with a focus on clinical signs that suggest underlying intestinal disease.

Gastrointestinal disease is very common in adult horses. Clinical signs depend on the underlying pathophysiologic processes and area of intestinal tract affected.

This article will focus primarily on chronic intestinal diseases, and acute colic and acute colitis will not be covered.

Weight loss is one of the most common clinical signs of chronic intestinal disease (Figure 1). In milder cases, this may manifest as a horse that is in adequate body condition, despite a high plane of nutrition. Poor muscle mass and a rough hair coat are also frequently reported. Lethargy and reduced performance are also common.

More specific clinical signs include poor appetite, colic and diarrhoea. In general, horses with more proximal disease (gastric or small intestinal) are more likely to demonstrate clinical signs of reduced appetite, colic (often after eating) and weight loss. Disease of the large intestine is much more likely to be associated with the presence of diarrhoea.

Evaluation should begin with a careful history. This should include assessment of signalment, use, previous problems and presenting clinical signs. Careful attention should be paid to diet, deworming, an owner’s perception of appetite and body condition, general energy level and presence or absence of specific abnormalities, such as colic or diarrhoea. General management should be assessed, including the horse’s access to pasture (including soil type), length of time at pasture, access to forage and forage type, exercise routine and exercise frequency. The presence of any stereotypical behaviours, such as crib-biting or windsucking, should also be assessed.

A thorough physical examination should be carried out in any horse with suspected intestinal disease. Specific attention should be paid to the gastrointestinal tract, including assessment of faecal character, gastrointestinal motility and body condition. Borborygmi should be assessed in all four abdominal quadrants.

Auscultation of the ventral abdomen can also be useful to identify the presence of sand. However, a thorough examination of all body systems is essential, as multisystemic disease is common.

Careful assessment of the cardiovascular system should be performed to look for evidence of systemic inflammation and assess hydration status. The presence of ventral or distal limb oedema should be noted, as this is often an indicator of hypoproteinaemia (Figure 2). Rectal examination should be carried out as part of initial assessment if appropriate.

After careful clinical assessment, it is usually necessary to carry out further diagnostic testing. A minimum database of haematology and biochemistry is usually a good starting point. Table 1 shows some of the common abnormalities that are identified in horses with chronic gastrointestinal disease.

| Table 1. Common clinicopathologic abnormalities seen with chronic gastrointestinal disease | |

|---|---|

| Clinicopathologic abnormality | Common cause |

| Anaemia | Chronic disease |

| Leucopenia and increased serum amyloid A concentration | Acute inflammation |

| Eosinophilia | Endoparasitism or generalised intestinal inflammation |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | Protein-losing enteropathy |

| Leucocytosis, hyperglobulinaemia and hyperfibrinogenaemia | Chronic inflammation |

Assessment of protein concentrations is particularly important. Hypoalbuminaemia (even if mild) is most commonly an indicator of intestinal protein loss (rarely occurs for other reasons such as renal loss or third space fluid loss) and is often a key indicator of the presence of intestinal disease. Chronic endoparasitism or cyathostomiasis should always be considered as a possible cause of intestinal disease. Common indicators of this include eosinophilia, hypoalbuminaemia and hyperglobulinaemia. Globulin electrophoresis can be used to evaluate the globulin fraction if increased. An increased beta-1 fraction suggests a response to cyathostomiasis.

Many horses with chronic intestinal disease will also have mild increases in other tissue enzymes. Serum alkaline phosphatase can originate from the intestinal tract and can be increased. Liver enzymes (such as gamma-glutamyl transferase) can be mildly increased secondary to intestinal disease. Similarly, bile acid concentration can also be mildly increased due to anorexia or decreased enterohepatic recycling.

An increased urea concentration is also a common finding – especially in thin horses. Provided creatinine concentration is normal, this usually indicates protein catabolism rather than renal dysfunction. Measurement of serum electrolytes can be useful in horses with diarrhoea and the presence of hypercalcaemia is often an indicator of neoplasia.

Specific laboratory tests should be considered in certain circumstances. Assessment of a faecal worm egg count, tapeworm serology and small redworm serology are often appropriate to assess likelihood of significant endoparasitism. Measurement of thymidine kinase concentration has been recently proposed as a biomarker for the detection of lymphoma, although the test sensitivity is relatively low.

Faecal testing for infectious disease can be useful in horses with diarrhoea. Chronic salmonellosis can be associated with poor body condition and is not always associated with profuse diarrhoea.

Submitting faeces for a diarrhoea panel is often the most cost-effective way to do this. Sedimentation can be used to check for the presence of sand. This can be done simply by suspending faeces in water in a glove and allowing the material to settle. If sand is present, it can be identified in the tips of the fingers.

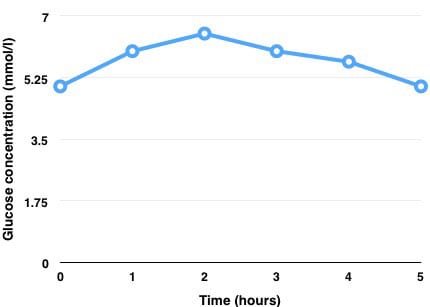

An oral glucose absorption test is a useful way to assess small intestinal absorption – 1g/kg of glucose should be given as a 20% solution via nasogastric tube after a 12-hour fast. Samples for glucose estimation should be taken at baseline and then hourly for four to five hours.

A normal horse will have a glucose peak of double baseline. A peak of less than 175% is usually considered to indicate partial malabsorption. Significant malabsorption is suspected in horses with a peak of less than 150% (Figure 3).

Gastroscopy can be used to assess for the presence of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS), and also to allow small duodenal biopsies to be collected for histology. It must be remembered EGUS can occur secondary to disease elsewhere in the intestinal tract, and mild EGUS is rarely the only cause of significant weight loss.

Rectal biopsies can also be easily collected from a sedated horse. In many instances, these biopsies are too superficial and too distant from the sites of diseased intestine to provide a diagnosis. However, duodenal biopsies often aid with a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and rectal biopsies can show evidence of cyathostomiasis and diffuse neoplasia.

More invasive biopsies are often needed to confirm a diagnosis, and these samples need to be collected by abdominal surgery. Standing laparoscopy can be used to visualise certain parts of the abdomen and collect intestinal biopsies. This is useful in cases where diagnosis is strongly suspected before surgery and the affected intestine is thought to be in a location readily accessible. However, in many cases, exploratory laparotomy is superior as it allows better visualisation of internal organs and the whole intestinal tract.

Abdominocentesis can be performed to collect peritoneal fluid for cytology. This often only provides evidence of a mild inflammatory response, but certain types of neoplasia can be exfoliative (haemangiosarcoma, melanomas, occasionally lymphoma) and in these cases cytology can be diagnostic.

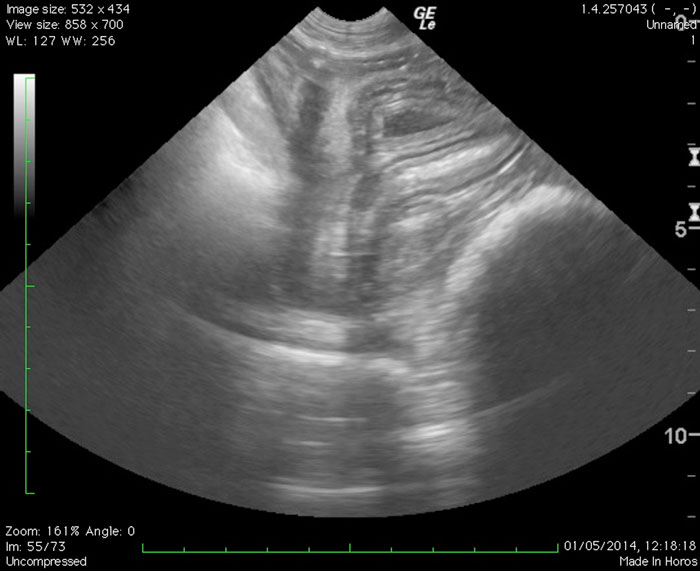

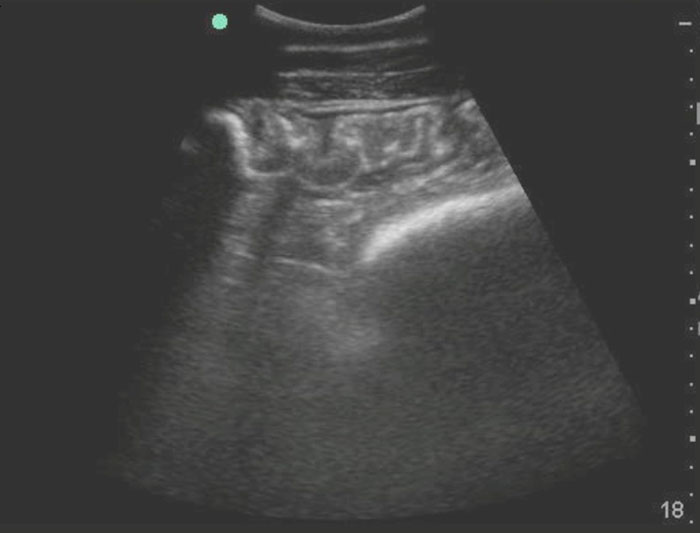

Ultrasound is probably the most useful tool for the evaluation of chronic intestinal disease. A large proportion of the abdominal cavity can be evaluated using a low-frequency curvilinear probe (2MHz to 5MHz).

Ultrasound allows visualisation of internal organs (spleen, liver or kidney) and significant amounts of the intestinal tract. This usually allows identification of the most severely affected area of the intestinal tract. The mural thickness of the small and large intestine should be evaluated.

The abdomen should be screened for the presence of enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, excess peritoneal fluid and other abnormal structures and findings. Figures 4 and 5 show examples of abnormal ultrasound findings.

EGUS is a diagnosis that is very popular with clients. However, EGUS is rarely a sole cause of weight loss. If EGUS is identified in a horse with hypoproteinaemia, significant recurrent colic or weight loss then careful evaluation of the whole intestinal tract should be evaluated. It is becoming increasingly recognised that equine glandular gastric disease occurs in a subset of horses with IBD. EGUS should only be diagnosed by gastroscopy.

Treatment for EGUS should be considered if the degree of ulceration is judged to be significantly severe (at least grade 2 or more of squamous disease and moderate or greater glandular disease), or when anorexia is a major clinical sign.

Oral omeprazole should be used as first-line therapy for the treatment of squamous disease. Less agreement exists about the most effective first-line treatment for glandular disease, but injectable omeprazole or oral misoprostol are generally considered to be the most effective. A full discussion of EGUS is beyond the scope of this article.

IBD is one of the most common causes of chronic intestinal disease in the horse. Clinical signs are often quite vague and non-specific, but affected horses usually show weight loss, lethargy, poor coat quality and mild hypoalbuminaemia.

An oral glucose absorption test may show reduced efficacy of small intestinal absorption, and ultrasound may reveal increased intramural thickening of the small intestine.

The underlying cause of IBD in the horse is not well understood. Different patterns of inflammation are identified histologically, including granulomatous, eosinophilic, lymphocytic-plasmacytic enterocolitis and proliferative. These conditions are suspected to be related to chronic antigenic stimulation from ingested allergens in food or sometimes endoparasites.

Specific infectious agents have not been identified. Evidence has shown IBD can affect intestinal motility.

The main treatment for IBD is corticosteroids. Prednisolone can be used, but many horses respond better to dexamethasone, which is a more potent anti-inflammatory.

Azathioprine can also be used in some cases as an immunomodulator. This drug is often less effective, but can be useful as an additional therapy or in cases where corticosteroids are contraindicated.

Dietary modification is also important in horses with IBD. Many horses seem to respond better to diets that are relatively high in fat and low in non-structural carbohydrates. Anthelmintic treatment is also indicated if there is any question about concurrent endoparasitism.

Lymphoma is the most common neoplasia seen in the horse. Clinical signs are often very similar to those seen in horses with IBD. In the early stages of lymphoma, the two conditions are very difficult to distinguish from each other. Alimentary lymphoma involves neoplastic infiltration of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Some horses present with generalised lymphoma present, with multiple organ involvement.

Antemortem diagnosis of lymphoma is difficult without surgical biopsies. An increased concentration of thymidine kinase can be useful and, in some cases, a high index of suspicion can be gained from rectal or duodenal biopsies.

Treatment of lymphoma is difficult and prognosis is poor. Chemotherapy is possible, but rarely undertaken. Some horses show an initial partial response to corticosteroids.

A wide variety of underlying problems can cause colitis in horses. These range from infectious diseases, such as chronic salmonellosis, to mechanical irritation from sand. Parasitic causes are also very common, and with ever-increasing anthelmintic resistance, cyathostomiasis is probably the most commonly observed cause of colitis.

Right dorsal colitis caused by NSAID use can also be seen. Some horses with IBD will also have large intestinal involvement.

Many horses with colitis will have soft to liquid faeces. Albumin concentration is often low and inflammatory markers are often increased. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen is useful to evaluate the degree of large intestinal inflammation. Faecal testing should be considered in horses where infectious disease is suspected. Radiography of the abdomen can also be useful to confirm the presence of sand in the colon.

Treatment of colitis depends on the underlying cause. Antimicrobials are rarely indicated. Corticosteroids can be useful in horses with inflammatory conditions (IBD and cyathostomiasis). Psyllium should be used for horses with sand colitis. Anthelmintic treatment is indicated in horses with cyathostomiasis, but should be managed carefully as worming can be associated with increased inflammation of the colon.

Dietary management is also important. Some horses with chronic colitis will often benefit from a diet based on predominantly short stem fibre, as this can help decrease the workload of the colon. Treatment with sucralfate and misoprostol can be useful in some cases.

In summary, chronic gastrointestinal disease is common in horses. Evaluation should start with a through history and a careful clinical evaluation. Diagnostic tests that may be useful include bloodwork, abdominal ultrasound, peritoneal fluid analysis and, in some cases, analysis of tissue samples. Treatment depends on the underlying cause, but for the majority of horses with chronic inflammatory disease the mainstay of treatment involves the use of glucocorticoids in addition to dietary management.