13 Jul 2022

Investigating and diagnosing lower airway inflammation conditions

Ill-thrift and poor performance in horses are commonly caused by lower airway inflammation issues. Fortunately, innovations have led to better assessment and management – as Ann Derham explains.

Lower airway inflammatory conditions are a common cause of poor performance and ill-thrift in horses. The underlying cause of lower airway inflammation can be non-infectious or infectious.

A thorough investigation is required to correctly diagnose the underlying issue and treat the patient correctly. New techniques have been developed in recent years, allowing for a greater assessment of the lower respiratory tract in horses, which, in turn, has resulted in better management of lower respiratory tract inflammation in these patients. This article’s aim is to run through the approach to investigation and diagnosis of lower airway inflammation in horses.

Signalment

Age is an important factor to consider, as some conditions are more typical in certain age groups. For example, the mild-moderate form of equine asthma is seen in young horses (younger than seven years), the severe form is more common in older horses (older than seven years), while in foals, an infectious inflammatory airway condition is far more likely.

History

Getting a detailed history of the patient is a critical step. A good history can help you to narrow down the differentials list, and offer clues as to the underlying cause/issue(s). Some important information that is needed from the client includes:

- Previous respiratory issues: nasal discharge (bilateral, unilateral and colour), coughing (at rest in the stable, at exercise, one/multiple coughs, productive or not).

- Previous treatment for a respiratory issue (including what was given and whether any improvement was seen).

- Recent transport.

- Management (including type of bedding, feed, whether in a barn or stable, and how long the horse is stabled for).

- Exercise (whether the horse is performing well, making a noise at work, takes a long time to recover or is coughing at exercise).

- Any recent changes to the diet, housing or field companions.

Clinical exam

A thorough clinical examination is the most important part of examining any horse with lower airway inflammation. While it won’t allow you to make a primary diagnosis, a thorough clinical exam and a detailed history should enable you to make a decision about underlying causes, and what diagnostics are then required.

Prior to beginning the clinical examination, carefully watch the horse at rest in its stable. This will allow you to get a more accurate resting respiratory rate and will also allow you to observe if an abdominal effort to the breathing can be seen, or a heave line is present. Following this, the clinical examination should be performed, with particular attention paid to the following:

- Respiratory tract: check the airflow in both nostrils, and whether any nasal discharge, asymmetry of the head, inspiratory/expiratory noise at rest or auscultate left and right lung fields (wheezes, crackles, general increased lung sounds) can be noted.

- Cardiovascular system: heart rate and rhythm, and murmurs.

- Temperature: pyrexia is commonly seen in infectious lower inflammatory airway conditions.

Once the clinical examination is finished, a rebreathing exam (Figure 1) should be performed. This involves placing a plastic bag over the horse’s nose (large enough to allow for several breaths). The horse breathes the same air in and out, increasing the horse’s carbon dioxide levels, resulting in the horse taking deeper breaths. The bag is then removed, causing the horse to take very deep breaths initially before returning to normal respiration. During the rebreathing exam, the lung fields are carefully auscultated, as you can hear the movement of air in the periphery of the lungs. The horse’s tolerance for this exam is very important, and the bag is removed immediately if the horse starts to cough or become distressed.

Diagnostics

An accurate diagnosis of the underlying disorder is a prerequisite for successful management of lower airway inflammation in horses. In some cases, clinical signs and history alone may be enough for a diagnosis. Depending on the underlying cause(s), different diagnostics may be required. Coughing, nasal discharge, dyspnoea, fever, exercise intolerance or increased mucus on endoscopy are strong indicators for collecting samples from the lower respiratory tract.

The most common techniques performed are now detailed.

Endoscopy

- This allows visualisation of the respiratory tract, and evaluation of the tracheal mucosa (degree of hyperaemia) and its luminal contents (degree of mucus, mucopurulent secretions and blood), which can assist interpretation of cytologic results (Figure 2).

- The lower respiratory tract (LRT) should have little/no mucus present.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL)

- The sample represents the lung periphery.

- BAL is recommended for cases of suspected equine asthma, and exercise-induced pulmonary haemorrhage as it is considered to be a more sensitive technique for identifying such cases1.

- This procedure is best tolerated with sedation. A BAL tube is passed into the trachea and 10ml of lidocaine is instilled into the trachea. The tube is then passed further down into the trachea until a slight resistance is felt, a further 10ml lidocaine is instilled and the cuff on the BAL tube is inflated. Sterile physiological saline is then instilled, 30ml in two 50ml syringes (60ml in total), and the fluid is aspirated. It is critical that the fluid aspirated contains surfactant (seen as white foam on top of the sample) for it to be of diagnostic quality. If no fluid is retrieved, moving the tube very slightly can help, or failing this a further 30ml to 50ml can be instilled. Once an adequate sample is retrieved, the cuff is deflated and the tube removed.

- Poor performance horses have abnormalities in cytology, such as increased neutrophils, mast cells, lymphocytes or eosinophils2.

Tracheal aspirate (TA)

- Sample includes secretions that pool in the trachea from anywhere in the lung.

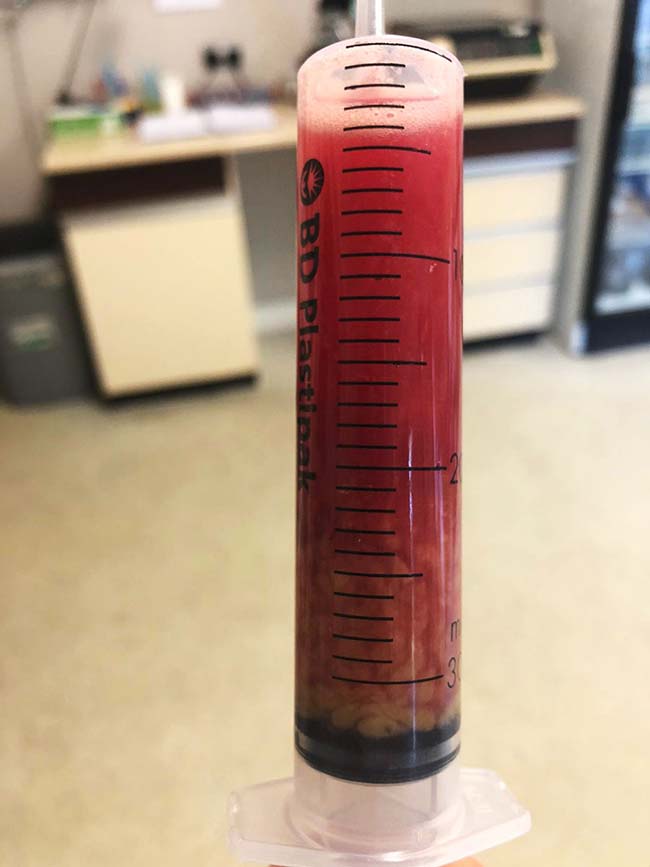

- Used in cases of suspected bacterial pneumonia/pleuropneumonia (Figure 3).

- In most horses, fluid accumulates in a pool in a ventrally depressed area in the trachea in front of the carina at the level of the thoracic inlet, where it can be aspirated.

Unguarded catheter technique:

- Done via a fibreoptic endoscope.

- Suitable for cytology only as it is contaminated with nasopharyngeal bacteria, so is unsuitable for microbial culture.

- As an example, a small polyethylene catheter is passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope, and 10ml to 15ml of sterile isotonic saline is instilled.

Guarded catheter technique:

- The catheter is passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. The outer catheter maintains sterility of the inner catheter as it is passed through the scope and trachea. The inner catheter is then used for retrieval of the sample aseptically.

- Advantages: it is non-invasive, quick to do and allows visualisation of the airways and guidance of the catheter; the sample is also suitable for microbiological culture.

- Factors that help prevent contamination: rapid sample collection, uses a small volume of fluid (10ml to 15ml) and only the inner catheter is advanced into the tracheal puddle.

- If the horse coughs often during sample collection, the sample should not be submitted for culture.

Transtracheal (percutaneous) aspiration technique:

- Sedation is required. This technique is invasive, and complications are possible, such as subcutaneous abscessation, tracheal haemorrhage, chondritis and pneumomediastinum. However, using good aseptic technique significantly reduces the risk of these.

- A pre-made kit can be used, or a cheaper alternative is to use a short stay 12g IV catheter and a 5Fr urinary dog catheter with the tip cut off obliquely.

- The trachea is identified on midline around a third to half way down the neck and an area of around 6cm by 6cm is clipped and aseptically prepared. A bleb of local anaesthetic is injected subcutaneously over the ventral midline (Figure 4a), and a stab incision is made through the skin and subcutaneous tissue with a number 15 scalpel blade (Figure 4b). The trachea is then stabilised with one hand and the catheter is introduced into the tracheal lumen between two cartilage rings (Figure 4c). The stylet is removed, and the urinary catheter is passed down into the tracheal lumen to the level of the thoracic inlet, where the saline is instilled and the sample aspirated (Figure 4d). Then 20ml to 30ml of sterile isotonic saline is enough for a sample. Once the sample is collected, the urinary catheter is withdrawn first, while the 12g catheter is left in place. This is done to minimise contamination of the peritracheal tissues. The 12g catheter is then removed and a sterile bandage applied to minimise any haemorrhage. This bandage is then removed after a few hours so that the site can be monitored.

- Advantages include reduced chance of contamination from the upper respiratory tract, and it can be considerably cheaper to perform if using the urinary and IV catheter method – especially on multiple horses.

In unresolved cases (such as around poor performance), it may be necessary to do both a TA and BAL to assess the overall health of the respiratory tract. The most important consideration when choosing a technique is whether microbiologic culture of the tracheobronchial secretions is indicated.

Thoracic ultrasound

This should be performed in any horse (adult or foal) that is presented with signs of respiratory distress, respiratory issues coupled with a fever or with a recent history of long-haul transport. Ultrasound is the preferred method for diagnosing pleuropneumonia in horses and allows for localisation and determination of the extent of the disease, it also allows the clinician to characterise the pleural fluid (if any), which is usually found in the most ventral part of the thorax. Thoracic ultrasound can also be used to guide thoracocentesis if needed.

Cytology

Cytology should be performed on all BAL and TA samples, as without cytology inappropriate treatment protocols may be initiated. Key points to remember when looking at cytology include:

- Most athletic horses with excess white mucus and markedly elevated neutrophils do not have a septic process. These are more likely to be cases of non-septic inflammatory airway disease.

- The presence of intracellular fungal spores or hyphae does not mean that the horse has fungal pneumonia, and are more likely due to environmental contamination.

- After respiratory tract haemorrhage, red blood cells in the airways are rapidly phagocytosed and degraded to haemosiderophages. A recent haemorrhage is indicated if the haemosiderophages are an olive-green colour. Haemosiderophages can be present for months after the haemorrhage has occurred.

- Presence of squamous epithelial cells in a tracheal aspirate sample indicates upper respiratory tract contamination and the sample is not suitable for microbial culture.

Microbial culture

Microbial cultures should be interpreted with caution. The presence of bacteria alone from a tracheal aspirate is not enough to confirm bacterial infection as they may also be due to sample contamination or a transient lower airway population.

Aspirates from lower respiratory tract infections (bacterial) will also have increased mucus, total cell and neutrophil counts, along with degenerative neutrophils. Typically, tracheal aspirate samples are plated on blood agar, anaerobic, fungal and neomycin plates. Quantitative cultures determine the number of colony-forming units of each species, which provides further information regarding the significance of a species being identified3.

Conclusion

Lower airway inflammation is a common cause of poor performance and ill-thrift in horses.

A thorough history and clinical examination will help the clinician decide which diagnostics are most appropriate (BAL versus TA, or both). Cytological examination should be performed in all cases, and microbial culture is indicated when a concern exists regarding an infectious process. Thoracic ultrasound is required for any cases with suspected pneumonia/pleuropneumonia.

References

- Pirie RS (2014). Recurrent airway obstruction: a review, Equine Vet J 46(3): 276-288.

- Hermange T, Le Corre S, Bizon C, Richard EA and Couroucé A (2019). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from both lungs in horses: diagnostic reliability of cytology from pooled samples, Vet J 244: 28-33.

- Hodgson JL and Hodgson DR (2003). Tracheal aspirates: indications, technique and interpretation. In Robinson NE (ed), Robinson’s Current Therapy in Equine Medicine (5th edn), Saunders Elsevier, St Louis: 401-406.