1 Jul 2025

Latest research on equine glandular gastric disease

Imogen Johns BVSc, FHEA, DipACVIM, FRCVS gives a review of recent studies and information on diagnostic and management options on this issue.

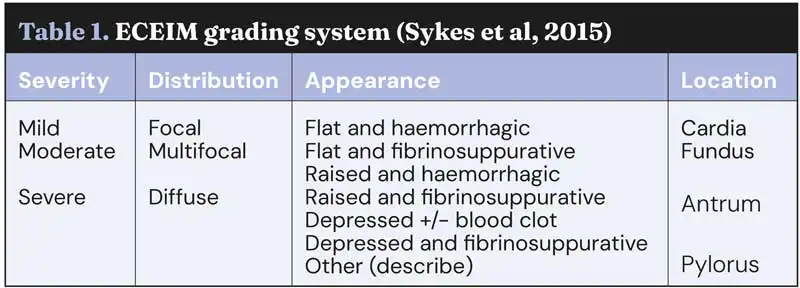

Figure 1. Mild multifocal flat and haemorrhagic, antrum.

During the “infancy” of equine gastroscopy and gastric ulcer research, lesions of the squamous mucosa were considered most relevant, with limited focus on changes in the mucosa of the glandular region.

However, we now know that equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD) is a different entity from equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD), and while some similarities exist between the two conditions, they should be considered as separate conditions with different risk factors, pathophysiology and response to treatment.

Much research in the past has focused on ESGD, and this article will aim to summarise the latest research on diagnosis of, and management options for, EGGD.

Diagnosis

A wide variety of clinical signs have been associated with the presence of lesions of the glandular mucosa; however, little correlation appears to exist between owner-reported clinical signs and the presence or absence of lesions; as such, clinical signs alone should not be used to diagnose EGGD (Hewetson et al, 2021).

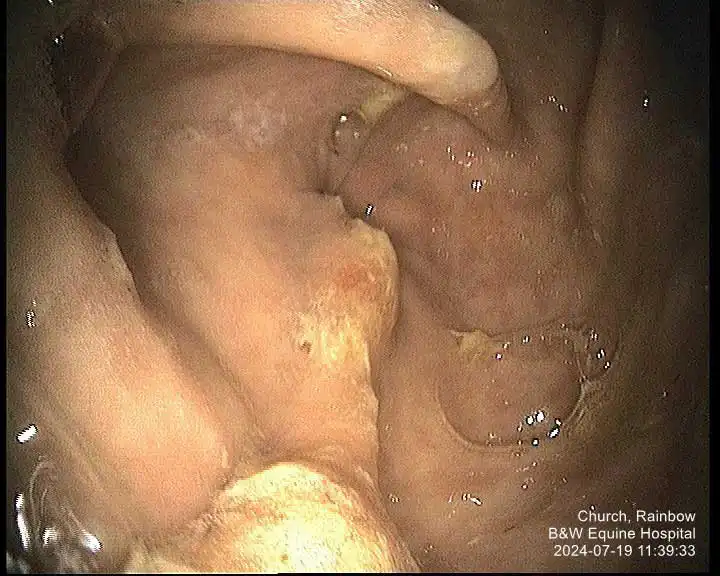

Gastroscopy with visualisation of the glandular mucosa – in particular, the pylorus and the antrum – remains the only way to definitively diagnose EGGD, although determining the significance of observed lesions can be challenging. Visualisation of the pylorus is sometimes hampered by the presence of feed material.

This can be minimised by ensuring an appropriate period of starvation (12 hours is typically sufficient) without access to any “edible” bedding. In some instances, a muzzle will be needed to prevent ingestion of bedding (and in some cases, droppings). Insufflation of air via the gastroscope will also help with visualisation of the pylorus if excessive liquid is still present at the time of scoping. If solid feed material is still present in the stomach after approximately 14 hours of starvation, delayed gastric emptying should be considered.

To help ascertain both the potential aetiology and clinical significance of visible lesions, transendoscopic biopsies can be obtained. Interestingly, in one study five out of seven horses with normal glandular appearance had evidence of mild gastritis, severe gastritis was identified in horses with mild EGGD, and mild-moderate gastritis was identified in all EGGD grades. Based on these results, the authors suggested that mucosal biopsies were considered of limited value in predicting underlying disease (Crumpton et al, 2015).

Scoring systems

Our understanding of the relevance of EGGD to equine health is hampered by our limited understanding of the severity and, therefore, significance of the observed lesions. Hierarchical scoring systems are typically used to help determine the clinical relevance of lesions.

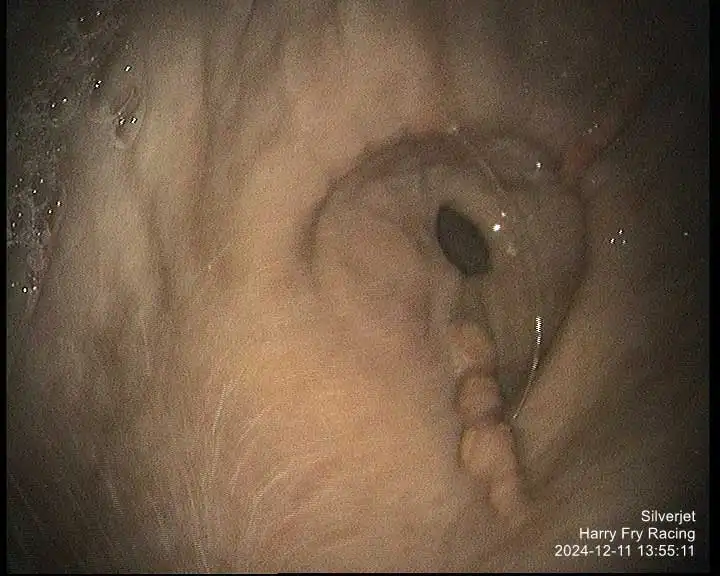

While several scoring systems have been utilised for grading of EGGD, because we lack the evidence to know which lesion appearance correlates to more severe disease, their ability to grade lesions is currently unclear. A scoring system developed for ESGD was initially utilised for EGGD (Andrews et al, 1999). However, with limited evidence to suggest higher grades correlated to worse clinical signs, a descriptive system was recommended in the European College of Equine Internal Medicine (ECEIM) consensus statement in 2015 (Sykes et al, 2015).

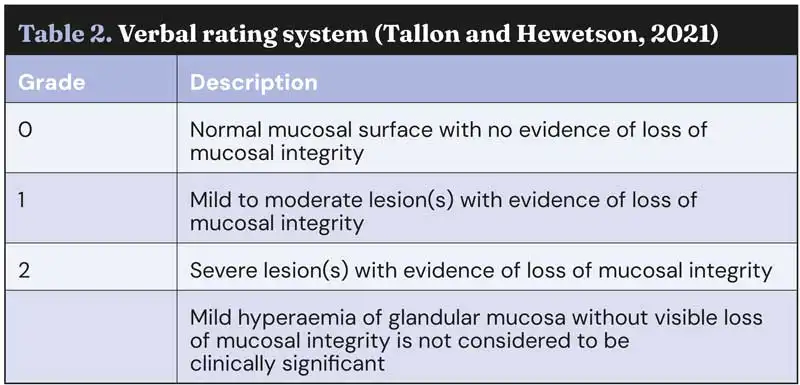

This system describes the distribution, shape, appearance and severity of lesions (see Table 1; Figures 1-7), but has been shown to have poor inter-observer variability (Pratt et al, 2022). Several numerical scoring systems have subsequently been developed in an attempt to provide a more objective assessment of lesion healing – especially when applied in a research setting.

These include a verbal rating scale (VRS) with 0 being normal and 2 being severe lesion or lesions (Sykes et al, 2017; Tallon and Hewetson, 2021), and a 1-4 scale modified from the original Equine Gastric Ulcer Council (see Table 2; Sykes and Jokisalo, 2014).

None of these scoring systems have been universally accepted, and inter-observer agreement is often limited, making it difficult to know how to best describe glandular lesions. Regardless of the system used, consistency in applying that system is probably the most important factor in considering response to treatment. In the author’s opinion, the ECEIM descriptive system works the best in clinical practice, although owners often want to know “the grade” and in that case, the VRS may be helpful.

Pathophysiology and risk factors

In contrast to ESGD, the underlying pathophysiology of EGGD remains poorly understood (Banse and Andrews, 2019). The glandular mucosa is well protected from the normal acid environment, and it is thought that lesions develop when a breakdown of those normal defences occurs. The reasons that these defences might fail are unclear, but certain risk factors for the development of disease have been identified.

Evidence suggests that increasing amounts of exercise is a risk factor for EGGD. In both Thoroughbred racehorses and warmblood horses, increasing number of days in work per week increased the risk of EGG, and in endurance horses the risk of EGGD doubles during a competition season (Pedersen et al ,2018; Sykes at al, 2019; Tamzali et al, 2011). It is hypothesised that alterations in the mucosal blood flow occurring during exercise predispose the mucosa to acid damage, although evidence for this in horses is lacking. An increasing number of riders/handlers was also identified in one study as a risk factor, and horses with EGGD have also been shown to have higher cortisol responses to adrenocorticotropic hormone stimulation, suggesting that “stress” may be a risk factor (Scheidegger et al, 2017).

Much recent interest has been shown in the role of the microbiome in health and disease, and several studies have investigated the gastric microbiome characteristics of horses with EGGD. While differences have been detected in the gastric microbial population of horses with and without EGGD, and in normal pyloric mucosal samples and those taken from pyloric lesions, at present it is not possible to determine whether these differences are causative or a consequence of the disease (Paul et al, 2021; Paul et al, 2023).

Treatment

Although exposure to gastric acid and subsequent acid injury is not considered to be the inciting cause of EGGD lesions in horses, acid suppression is key to effective treatment (Rendle et al, 2021; Rendle and Gough, 2025).

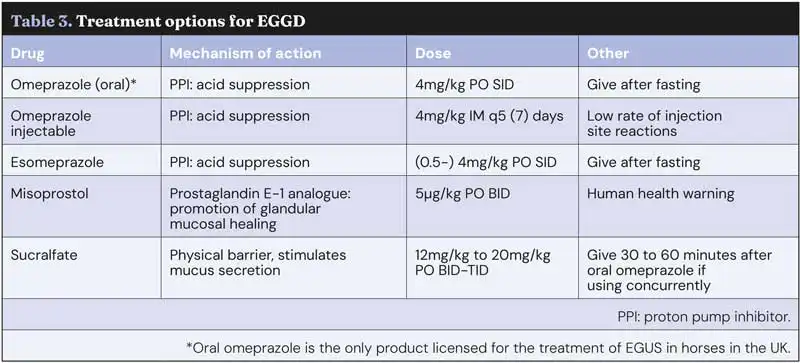

One of the challenges in comparing the efficacy of various treatments is a lack of consensus on what constitutes healing, with some studies defining healing as a return of the mucosa to a normal appearance, while others consider that healing has occurred with a mild degree of residual erythema. In general, if presenting clinical signs have resolved, then mild erythema of the mucosa appears unlikely to be of clinical significance and long-term treatment “chasing” a normal mucosa may not be warranted. Treatment options are summarised in Table 3.

Omeprazole

Omeprazole is a proton pump inhibitor that results in suppression of gastric acid production and subsequent increase in intra-gastric pH. Multiple oral omeprazole formulations are licensed for use in the treatment of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) in horses in the UK, with no evidence to suggest that one product is superior to another. Omeprazole needs to be protected from the acidic environment of the stomach to ensure it is not inactivated prior to absorption, so formulations are typically enteric coated/buffered.

In contrast to good response rates in horses with ESGD, most studies in horses with EGGD have shown a relatively poor response to treatment with oral omeprazole (with or without sucralfate). Healing rates vary from as low as 11% up to 63% (Rendle, 2021; Hepburn and Proudman, 2014). Comparison between studies is difficult, however, due to differing definitions of EGGD, a lack of consensus of what constitutes “healing” and variable management strategies, in particular whether the drug is administered in a fed or fasted state.

The bioavailability of oral omeprazole is increased when fed to fasted horses and, as such, withholding feed (typically overnight) is recommended to maximise efficacy. Because ad lib forage is typically recommended to help prevent the occurrence of gastric ulceration by ensuring consistent saliva production/buffering action, owners are often concerned that this will be detrimental.

However, horses have a diurnal pattern of eating and typically eat little between late at night and first thing in the morning, so the effect of a relatively short period of starvation on saliva production is likely to be minimal. Feeding should occur within 30 minutes of omeprazole administration, as it requires activation in response to feeding.

While various dose rates for treatment of EGSD have been investigated, 4mg/kg by mouth once daily is recommended for treatment of EGGD, as this is likely to have the most effective acid suppression. A treatment period of four weeks is recommended, although longer courses may be required.

Studies with long-acting injectable omeprazole suggest that a duration of effective acid suppression of as little as three weeks can result in healing of EGGD lesions. As such, if oral omeprazole is used and significant improvement has not been noted after four to six weeks of treatment, then longer-term treatment seems unlikely to be beneficial. Instead, attention to how the medication(s) are being given should be addressed, and if compliance is good, a change in treatment may be more sensible (for example, to esomeprazole or injectable omeprazole) rather than persisting with the same treatment for several months.

Slowly reducing the dose or oral omeprazole following resolution of disease has been suggested as a method to prevent “rebound hypergastrinaemia” and rapid recurrence of lesions, a syndrome that is reported in humans. Gastrin promotes acid secretion in the stomach and its production is inhibited by an acidic pH.

During treatment with omeprazole, gastrin production increases at least two fold in horses, with the concern that this increased production can persist for a prolonged period in horses following discontinuation of omeprazole, with possible recurrence of lesions. In a study of 12 horses treated for 57 days with oral omeprazole, gastrin concentrations increased during treatment, but rapidly (within two to four days) returned to pre-treatment levels, suggesting persistent hypergastrinaemia is not a feature of horses treated medium term with omeprazole.

Based on the findings of this study, the authors suggested that tapering the dose of omeprazole after resolution of disease is not necessary and, instead, management considerations directed at reducing risk should be implemented (Clark et al, 2023).

Long-acting injectable omeprazole

The disappointing healing rates for horses with EGGD has prompted investigation of other treatment options. Duration of acid suppression (such as the time in a 24-hour period during which the pH is above 4) is considered a key factor in effective treatment. At best, when administered at 4mg/kg by mouth once daily and in a fasted state, the duration of sufficient acid suppression with oral omeprazole is likely only 16 hours.

A long-acting injectable omeprazole formulation has been developed to enhance longer-term acid suppression (Sykes et al, 2017). Recent studies have suggested higher healing rates can be achieved compared to the oral product (or other oral medications). While originally prescribed as a course of four injections seven days apart, a recent study has suggested that a period of five days between injections may be more efficacious (Sundra et al, 2024).

In this retrospective study, 82 horses with EGGD were treated with either a five-day or seven-day period between injections, with repeat gastroscopy five to seven days following the last dose. Healing was defined in two ways: firstly, return of the gastric mucosa to a normal appearance; secondly, horses with only residual erythema were also considered healed.

Complete healing occurred in 39% of horses treated every seven days and 63% in horses treated every five days. When horses with residual erythema were also included in the “healed” category, 69% of horses treated every seven days had healed and 93% of horses treated every five days had healed.

Interestingly, when owners were asked whether the presenting clinical signs had resolved, improved or remained unchanged or worsened, no association was made between owner-perceived improvement in clinical signs and endoscopic improvement, highlighting our lack of understanding of the relevance of the appearance of lesions and their correlation (or not) with possible clinical signs.

Esomeprazole

Omeprazole is a racemic mixture of two enantiomers: S-omeprazole (or esomeprazole) and R-omeprazole. Because esomeprazole is more potent and results in more pronounced and consistent acid suppression in people, it is the most frequently prescribed proton pump inhibitor in humans.

Although a dose as low as 0.5mg/kg by mouth once daily (given following a 16-hour fast) was shown to result in effective acid suppression in a small number of horses, doses of 2mg/kg to 4mg/kg have been evaluated in studies in horses with naturally occurring disease.

In two very small studies totalling 9 horses, healing rates of 75% to 80% after 28 days were reported, and in a more recent randomised single-blinded controlled trial, 28 out of 51 horses (55%) treated with oral esomeprazole healed compared to 6 out of 24 (25% with omeprazole; Rendle, 2017; Sundra, 2021; Sundra et al, 2024). Although esomeprazole is considered more potent than omeprazole and results in a longer duration of acid suppression, administration after a period of feed deprivation is still recommended to maximise efficacy.

Sucralfate

Sucralfate is a complex polyammonium hydroxide salt, which may be beneficial when used in addition to omeprazole in the treatment of EGGD.

The potential beneficial effects (none of which have been proven in horses) are associated predominately with restitution of the normal mucosal barrier, and include providing a physical barrier to acid diffusion, stimulation of mucus secretion and inhibition of pepsin and bile acid release (Rendle and Gough, 2025).

Like omeprazole, efficacy of sucralfate is theoretically optimised when administered on an empty stomach, which presents some practical challenges for owners and may explain at least in part poor reported healing rates.

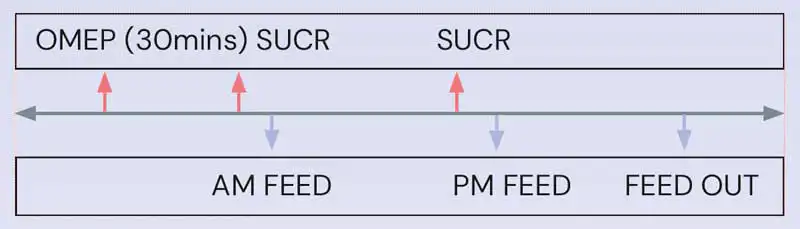

A suggested timeline for co-administration of oral omeprazole and sucralfate, which should maximise efficacy of both drugs, can be found in Figure 7.

Misoprostol

Misoprostol has been used in people for treatment of refractory peptic ulcer disease, and some evidence suggests that it may be beneficial in horses with EGGD.

Possible mechanisms to enhance healing include increasing mucosal blood flow, reducing gastric acid production, reducing inflammation and increasing blood flow. As with many EGGD studies, marked variation exists in reported efficacy, with healing rates ranging from 12% to 72% (Varley et al, 2019; Pickles et al, 2020; Pratt et al, 2023).

Because the drug is abortogenic, it is important that human health concerns are taken into account when misoprostol is prescribed.

Preventive strategies

Understandably, owners are very keen to implement strategies and supplements that will help prevent recurrence of disease. Unfortunately, as our understanding of the pathophysiology of EGGD is limited, providing evidence-based guidelines at present is not possible. Taking into account risk factors and potential beneficial effects of supplements, the following guidelines may be appropriate:

- Reduce exercise to four to five days per week.

- Minimise “stress”; this will be different for each horse, but keeping in mind the three “Fs” of forage, freedom and friends may be helpful.

- Reduce the number of handlers for the horse.

- Maximising turnout and minimising grain (high starch) concentrate feeding.

- Pectin-lecithin, either alone or in combination with Saccharomyces cervisiae and magnesium hydroxide, may be beneficial. Beet pulp has high levels of pectin and was associated with a lower risk of EGGD in one study.

- Oil supplementation is aimed at reducing inflammation, and as such the type of oil is important. Ideally, a fish-oil based product, but if not, flax-based products are preferred over corn or soy oil.

- Long-term low-dose treatment with omeprazole is unlikely to be beneficial in horses at risk of EGGD. “Pulse” treatment where omeprazole is given during times of increased perceived risk (competition and long-distance transport) may be more appropriate, although studies are lacking to show the efficacy of this strategy.

Key points

Injectable omeprazole appears superior to oral formulations for treatment of EGGD. If oral formulations are used, they should be given following an overnight fast and followed by a meal at least 30 minutes after administration. If sucralfate is used, the drugs should be given at separate times to ensure omeprazole bioavailability is maximised.

Preventive strategies should be aimed at minimising risk factors. Large prospective studies are needed to further clarify both the relevance of EGGD lesions, causative clinical signs, what “healing” is and the best treatment options.

- Article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 26, Pages 12-16

References

- Andrews FM, Bernard WDB, Cohen ND et al (1999). Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS): the Equine Gastric Ulcer Council, Equine Vet Educ 11(5): 262-272.

- Banse HE and Andrews FM (2019). Equine glandular gastric disease: prevalence, impact and management strategies, Vet Med 10: 69-76.

- Clark B, Steel C, Vokes J et al (2023). Evaluation of the effects of medium-term (57-day) omeprazole administration and of omeprazole discontinuation on serum gastrin and serum chromogranin A concentrations in the horse, J Vet Intern Med 37(4): 1,537-1,543.

- Crumpton SM, Baiker K, Hallowell GD et al (2015). Diagnostic value of gastric mucosal biopsies in horses with glandular disease, Equine Veterinary Journal 47(S48): 9.

- Hepburn RJ and Proudman CJ (2014). Treatment of ulceration of the gastric glandular mucosa: retrospective evaluation of omeprazole and sucralfate combination therapy in 204 sport and leisure horses (abstract), Proceedings of the 11th International Colic Symposium, Dublin.

- Hewetson M, Hoksbergen FS, Berger S et al (2021). Association between owner-perceived clinical signs and the presence of equine glandular disease on endoscopy, Equine Vet J 53(S55): 7-8.

- Huxford KE, Dart AJ, Perkins NR et al (2017). A pilot study comparing the effect of orally administered esomeprazole and omeprazole on gastric fluid pH in horses, N Z Vet J 65(6): 318-321.

- Paul LJ, Ericsson AC, Andrews FM et al (2021). Gastric microbiome in horses with and without equine glandular gastric disease, J Vet Intern Med 35(5): 2,458-2,464.

- Paul LJ, Ericsson AC, Andrews FM et al (2023). Field study examining the mucosal microbiome in equine glandular gastric disease, Plos One 18(12): e0295697.

- Pedersen SK, Cribb AE, Windeyer MC et al (2018). Risk factors for equine glandular and squamous gastric disease in show jumping Warmbloods, Equine Vet J 50(6): 747-751.

- Pickles KJ, Black K, Brunt O and Crane M (2020). Retrospective study of misoprostol treatment of equine glandular gastric disease. In: Proceedings of the European College of Equine Internal Medicine Congress, J Vet Intern Med 35(2): 1,177-1,193.

- Pratt SL, Bowen IM, Hallowell GD et al (2022). Assessment of agreement using the equine glandular gastric disease grading system in 84 cases, Vet Med Sci 8(4): 1,472-1,477.

- Pratt SL, Bowen M, Hallowell GH et al (2023). Does lesion type or severity predict outcome of therapy for horses with equine glandular gastric disease? – A retrospective study, Vet Med Sci 9(1): 150-157.

- Rendle D (2021). Treatment of equine glandular gastric disease in elite endurance horses with oral and long-acting injectable omeprazole: a randomised, blinded clinical trial, J Vet Intern Med 35: 666-668.

- Rendle DI (2017). Oral esomeprazole as a treatment for equine gastric ulcer syndrome refractory to oral omeprazole, Equine Vet J 49(S51): 25-26.

- Rendle D, Bowen M, Brazil T et al (2018). Recommendations for the management of equine glandular gastric disease, UK-Vet Equine 2(S1): 2–11.

- Rendle DI and Gough SL (2025). Pharmaceutical treatment of equine glandular gastric disease: a contextualised review of recent developments, Equine Vet Educ 37(5): 271-280.

- Scheidegger MD, Gerber V, Bruckmaier RM et al (2017). Increased adrenocortical response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in sport horses with equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD), Vet J 228: 7-12.

- Sundra T (2021). Esomeprazole in the treatment of equine glandular gastric disease, UK-Vet Equine 5(5): 216-219.

- Sundra T, Kelty E and Rendle D (2024). Five versus seven-day dosing intervals of extended-release injectable omeprazole in the treatment of equine squamous and glandular gastric disease, Equine Vet J 56(1): 51-58.

- Sykes BW, Bowen M, Habershon-Butcher J et al (2019). Management factors and clinical implications of glandular and squamous gastric disease in horses, J Vet Intern Med 33(1): 233-240.

- Sykes BW, Hewetson M, Hepburn RJ et al (2015). European College of Equine Internal Medicine consensus statement—equine gastric ulcer syndrome in adult horses, J Vet Intern Med 29(5): 1,288-1,299.

- Sykes B and Jokisalo J (2014). Rethinking equine gastric ulcer syndrome: part 1–terminology, clinical signs and diagnosis, Equine Vet Educ 26(10): 543-547.

- Sykes BW, Kathawala K, Song Y et al (2017). Preliminary investigations into a novel, long-acting, injectable, intramuscular formulation of omeprazole in the horse, Equine Vet J 49(6): 795-801.

- Tallon R and Hewetson M (2021). Inter-observer variability of two grading systems for equine glandular gastric disease, Equine Vet J 53(3): 495-502.

- Tamzali Y, Marguet C, Priymenko N and Lekeux P (2011). Prevalence of gastric ulcer syndrome in high-level endurance horses, Equine Vet J 43(2): 141-144.

- Varley G, Bowen IM, Habershon-Butcher JL et al (2019). Misoprostol is superior to combined omeprazole-sucralfate for the treatment of equine gastric glandular disease, Equine Vet J 51(5): 575-580.

- Vokes J, Lovett A and Sykes B (2023). Equine gastric ulcer syndrome: an update on current knowledge, Animals 13(7): 1,261.