17 Oct 2022

Managing obesity in horses

Nicola Menzies-Gow discusses the reasons behind horses and ponies gaining too much weight, its repercussions and prevention tools.

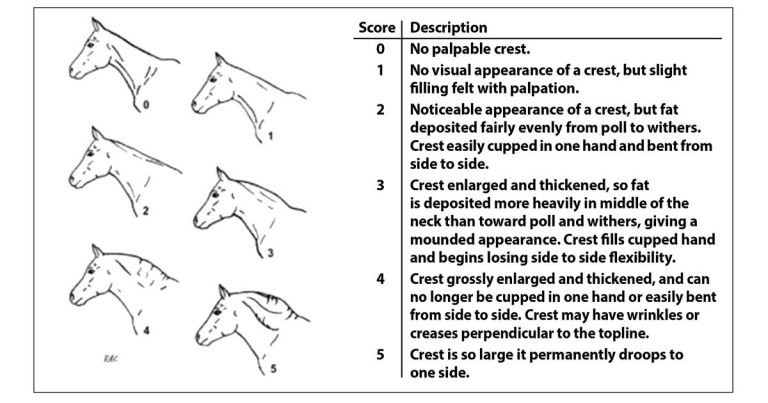

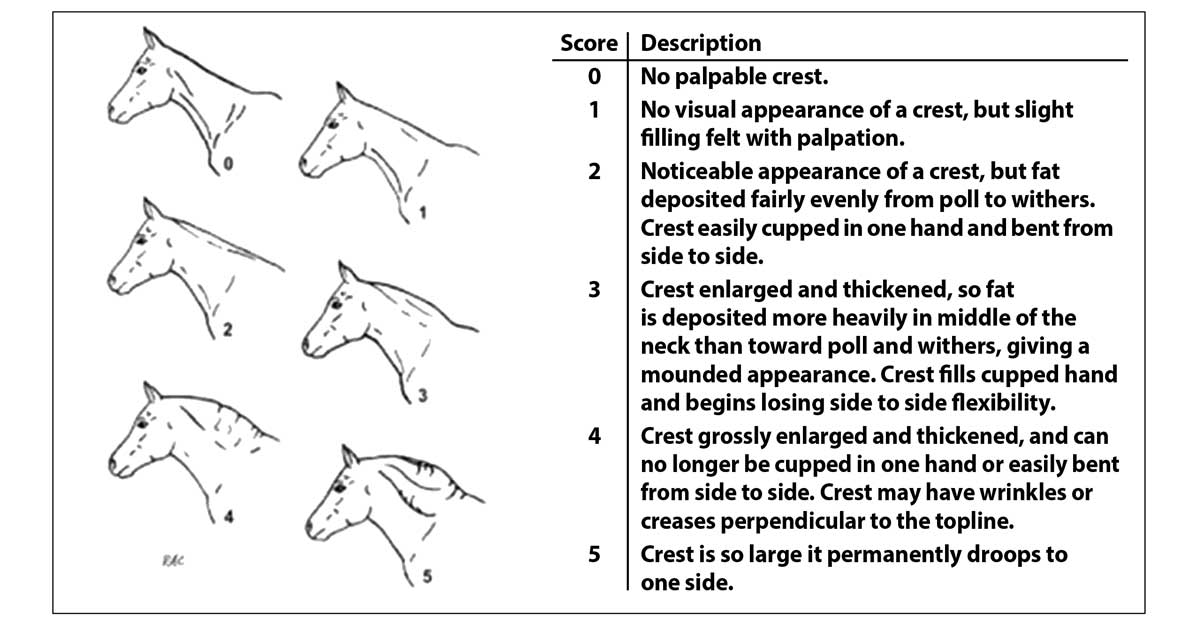

Figure 1. Cresty neck scoring7.

Equine obesity is a growing epidemic, with up to 70% of ponies being overweight or obese. Obesity has significant detrimental effects on health and conditions related to obesity in the horse, including an increased risk of laminitis, an increased risk of hyperlipaemia, exercise intolerance, reduced reproductive performance, mesenteric lipomas, osteochondrosis and hyperthermia. Therefore, an urgent need exists to educate both veterinarians and owners as to what constitutes an ideal body composition and the deleterious effects of obesity.

Obesity should be identified using body condition scoring. Dietary and exercise management changes can then be implemented to reduce adiposity and prevent the potentially life-threatening complications. Pharmacologic agents should be reserved for short-term use in animals that are weight loss resistant, cannot be exercised for lameness reasons or are at a high risk of laminitis and require more rapid weight loss than can be achieved with management changes alone.

The weight loss should be carefully monitored by the owner, with regular check-ins scheduled with the veterinarian and individualised achievable targets set. Once the target weight is achieved, it is important that monitoring of weight by the owner is continued to prevent relapse.

Obesity is defined as adiposity to an extent that it has a negative effect on health, leading to reduced life expectancy and/or increased health problems.

It is increasingly obvious that obesity is common, and has significant detrimental effects on the health of horses and ponies, similar to the human and companion animal population. While 26% of pet cats and 25% of pet dogs are overweight, UK studies have reported that around 50% of horses and ponies are fat or very fat1, with rates in some populations of native ponies being as high as 70%2.

Obesity is also more common in animals described as “good doers”, animals used for pleasure or non-ridden, and show or dressage animals2. In addition, owners consistently underestimate the level of obesity of their animals3 and the perception of ideal weight for show animals is greater than for other disciplines.

Why are horses getting fat?

The reasons that domesticated animals develop obesity are similar to those attributed to obesity in humans – namely physical inactivity combined with the consumption of excessive calories.

As a herbivorous species, horses have evolved to rely on grass forage alone for their nutritional requirements. Therefore, during the summer and autumn, horses should ingest increasing quantities of available forage and gain adiposity in preparation for the winter when food tends to be scarce.

Increased secretion of proopiomelanocortin by the pituitary pars intermedia during these seasons stimulates appetite and adipogenesis. These changes represent a critical survival mechanism, which ensures that stored energy in the form of body fat is available throughout the winter months.

Normally the period of food scarcity is finite and the acquired fat stores are depleted just prior to the onset of spring and resumption of grass growth. Therefore, in the wild, acquisition of adipose tissue in summer and autumn is essential for winter survival.

The development of insulin dysregulation (ID) is a critical component of this winter survival mechanism, which seems to develop and resolve in parallel with the acquisition and depletion of additional fat stores at the start and finish of winter, respectively.

The modern husbandry practices of providing excessive calories in the form of high-quality pasture and bucket feeds, physical inactivity, stabling and the use of rugs to help maintain body temperature year round all promote fat storage and/or decrease the use of stored fat – and, consequently, the acquisition of excessive adiposity and its chronic persistence. This is further compounded by owners striving for their horses to look their “best” year round.

The perception of “best” has morphed over time, from horses that are well muscled for work or sport to horses that are instead well covered in fat. Many owners do not appreciate the difference between muscling and fat deposition, and the trend towards promoting increased fat deposition has been re-enforced by rewarding obesity in the show and dressage arenas, and by the frequent depiction of obese horses as role models on websites, in the equestrian press and elsewhere.

Additionally, obesity is often trivialised with obese animals depicted in cartoons; the use of endearing terms such as “cuddly”, “tubby” or “podgy”; and the lack of a social stigma associated with keeping an obese animal. By contrast, the site of a thin or emaciated horse evokes horror and accusations of cruelty. The result is the persistence of obesity and hence ID year round.

Why shouldn’t we just let them stay fat?

Obesity has been shown to have a number of adverse systemic effects, including:

- Inflammation “metaflammation”: evidence exists of obesity being associated with systemic, adipose tissue and uterine inflammation.

- Oxidative stress: evidence exists that obesity is associated with systemic oxidative stress, as well as localised oxidative stress within the pancreatic islets and lamellar tissue.

- Stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis: evidence exists of obesity-associated stimulation of the HPA axis with increased free cortisol concentrations due to decreased binding proteins and altered tissue cortisol metabolism. Cortisol antagonises insulin and so this may contribute to ID.

- Disturbance of cortisol and lipid metabolism.

- Vascular and endothelial dysfunction.

- Altered faecal microbiome.

- Altered cell mediated immunity.

- A number of health disorders are associated with obesity in the horse, including:

- endocrinopathic laminitis

- increased risk of hyperlipaemia

- impaired thermoregulation

- decreased fertility

- osteochondrosis dissecans

- behavioural disorders

- increased blood pressure

- orthopaedic disease through increased loading

- preputial and mammary oedema and dermatitis

- ventral oedema

- colic as a result of pedunculated mesenteric lipomas

- inappropriate lactation

- reduced growth rates in foals of obese mares

- respiratory compromise and equine asthma

- pharyngeal collapse

Assessment of obesity

Obesity is most accurately assessed at postmortem by carcase dissection or administration of deuterium oxide4. However, in clinical practice, generalised obesity is assessed by body condition scoring5, which can be performed using a 0-5 (Table 1) or 0-9 scale6. The latter is more robust, but seems to be used more frequently in the research setting. Either scale is acceptable provided the denominator is stated.

| Table 1. Body condition scoring using the 0-5 scale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Neck | Withers | Back and loin | Ribs | Hindquarters |

| 0 very thin | Bone structure easily felt – no muscle shelf where neck meets shoulder |

Bone structure easily felt | Three points of vertebrae easily felt |

Each rib can be easily felt | Tail head and hip bones projecting |

| 1 thin | Can feel bone structure – slight shelf where neck meets shoulder |

Can feel bone structure | Spinous process can be easily felt – transverse processes have slight far covering |

Slight fat covering, but can still be felt | Can feel hip bones |

| 2 fair | Fat covering over bone structure |

Fat deposits over withers – dependent on conformation |

Fat over spinous processes | Can’t see ribs, but ribs can still be felt | Hip bones covered with fat |

| 3 good | Neck flows smoothly into shoulder |

Neck rounds out withers | Back is level | Layer of fat over ribs | Can’t feel hip bones |

| 4 fat | Fat deposited along neck | Fat padded around withers | Positive crease along back | Fat spongy over and between ribs | Can’t feel hip bones |

| 5 very fat | Bulging fat | Bulging fat | Deep positive crease | Pockets of fat | Pockets of fat |

Regional adiposity is assessed using cresty neck scoring (Figure 1).

Ultrasonographic measurements of fat depth at specific anatomic locations can be used to assess adiposity, but have their limitations8,9. The assessment of retroperitoneal fat depth by ultrasonographic examination of the ventral midline may be useful in demonstrating horses that are thin on the outside, but fat on the inside (so-called TOFIs).

Serum insulin and the adipose tissue-derived hormone adiponectin are independent risk factors for laminitis10, so measurement of both in overweight animals can be useful in persuading owners that their horse has metabolic disease and would benefit from a programme of weight loss.

Measurements of insulin concentration at baseline or after a carbohydrate challenge are useful in assessing laminitis risk9 and monitoring improvement in insulin sensitivity in response to weight loss.

Management of obesity

Obesity can be reduced predominantly through the implementation of a regime of dietary changes in conjunction with increased exercise in sound animals. An ideal target for weight loss is 0.5% to 1% of body mass (BM) weekly.

Feeding an overweight or obese animal

Overweight or obese animals should be fed a diet based on grass hay (or hay substitute) with low (less than 10%) non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) content and cereals avoided. A daily allowance of 1.25% to 1.5% of actual BM as dry matter intake (DMI) or 1.4% to 1.7% of actual BM as fed is widely recommended.

Soaking hay in water before feeding will leach water soluble carbohydrates; however, this does not reliably decrease the NSC content to less than 10% in every case11 and ideally forage should be analysed after soaking. It should be remembered that steaming hay does not reduce NSC content.

Feeding haylage should generally be avoided as haylage typically has a higher NSC content, is more palatable so intakes may be higher and seems to result in a greater insulin response than a comparable hay12. However, some haylage can have a low NSC content and if fed in restricted quantities may be suitable if it has been analysed.

Barley straw can be fed to maintain appropriate levels of fibre and total intake, while reducing calorie intake. A recent study demonstrated that horses fed a 50:50 hay:straw diet lost weight while those fed hay did not11.

The forage should be divided into three to four feeds per day and strategies employed to prolong feed intake time, such as use of hay nets with small holes, double hay netting, hay bags and hay nets hung from the ceiling in the middle of the stable.

In most overweight animals, any access to pasture is going to severely frustrate attempts at weight loss. It is therefore best to remove the horse from pasture, at least initially. When an animal is to be turned out to pasture, while this will have the beneficial effect of increased exercise and allow social interaction, methods to restrict intake should be used, such as strip grazing, track systems, restriction of turnout time, grass muzzles and keeping pasture height short through topping.

Forage-only diets do not provide adequate protein, minerals or vitamins and so a low-calorie commercial ration balancer product that contains sources of high-quality protein and a mixture of vitamins and minerals to balance the low vitamin E, vitamin, copper, zinc, selenium and other minerals typically found in mature grass hays is recommended.

Advice on feeding needs to be simple and specific for owners to be able to implement the changes in their daily life. For most owners, compliance will be improved if a specific “recipe” is provided, which dictates exactly what quantity of exactly what feed (that is, the trade name) is required.

Providing general advice and telling owners they need to feed 1.5% BM of a feed with less than 10% sugar is unlikely to result in good compliance, because it may be hard for them to put these figures into practice. Instead, vets should be dispensing weight tapes and luggage scales for weighing forage alongside a written feed plan.

Owners should be reminded that the use of a single scoop for different feeds can result in overfeeding as they measure volume rather than weight, with the weights of feeds varying considerably, and the scoop needs to be calibrated for each feed.

Finally, owners should be encouraged to weigh out the total amount of food for the day, before being subsequently split into separate portions. Creating and weighing individual portions has been seen to lead to a tendency to feed at the top end or even slightly over the recommended weight each time, and weighing once reduces the percentage error.

Exercise

Unless a musculoskeletal reason exists for not doing so, animals should be exercised daily, as this has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity and decrease food intake, as well as consume calories. Gradual increase in the intensity and duration of the exercise needs to be undertaken in any animal according to fitness level.

Recommendations around desired exercise levels are largely opinion based, yet, to achieve compliance, any exercise programme needs to be both specific and realistic. In a recent consensus statement13, the following exercise recommendations were made:

Horses without laminitis: heart rate 150 beats/minute to 170 beats/minute (fast trot to canter unridden) for at least 30 minutes, 5 or more times per week – however, this cannot be achieved from day one as it will depend on the initial fitness of the patient.

Horses with previous history of laminitis: low-intensity exercise on a soft area (heart rate 130 beats/minute to 150 beats/minute; canter to fast canter, ridden or unridden), 30 minutes, 3 days per week, always monitoring for signs of lameness.

Alternatively, a protocol for 50 minutes of exercise was proposed recently, with a 10-minute warm-up at walk and then alternating trot sets and walk breaks of 5 minutes each, finishing with a 5-minute cool down14. It was suggested that this protocol be performed 5 days per week. As horses become fitter, the trots sets can be replaced with canter.

Rugging

Horses are able to thermoregulate at temperatures between 5°C and 25°C, and therefore require no additional measures to control their body temperature such as rugs between these temperatures.

Horses that are acclimatised to lower temperatures are able to thermoregulate at temperatures as low as -10°C to -15°C. Above 10°C, horses prefer not to be rugged except in extreme wet/windy weather conditions. Therefore, if the weather is neither wet nor windy then rugs are only required below 5°C and acclimatised horses may only require rugs below temperatures as low as -10°C.

Unnecessary rugging represents a welfare concern in causing horses to become too hot in warmer weather, such that they are unable to thermoregulate, whereas depriving horses of rugs is less likely to impact on their welfare. Provision of a field shelter that provides protection from the wind and rain is a far better solution to cold weather than rugging. However, geriatric horses may be less able to thermoregulate at lower temperatures.

Pharmacologic agents

Pharmacologic agents should be considered for short-term use (three to six months) in animals that are weight loss resistant, cannot be exercised for lameness reasons or are at a high risk of laminitis and require more rapid weight loss than can be achieved with management changes alone.

Levothyroxine is the most appropriate pharmacologic treatment for promoting weight loss through speeding up the metabolic rate and has also been demonstrated to improve insulin sensitivity15. It is essential that compliance exists with the dietary recommendations when using levothyroxine or weight loss is unlikely to result due to the side effect of polyphagia.

No licensed product exists in the UK, therefore levothyroxine can be prescribed under the cascade at a dose of 0.1mg/kg by mouth once a day for a period of three to six months or until the target for weight loss is achieved. When treatment is to be discontinued, it is recommended that the dose is halved for two weeks, then halved again for a further two weeks before stopping treatment.

Monitoring weight loss

Weight loss in response to dietary restriction and increased exercise should be monitored every four to six weeks by the owner. Ideally this should be done using a weigh bridge. However, this is not usually possible. Instead, the most reliable method involves heart and belly girth measurement or use of a weight tape, as these will decrease as bodyweight decreases.

In contrast, body condition score will often remain unchanged for a prolonged period as it is a non-linear scale and marked weight loss will be required before the score will change, resulting in the owner becoming disheartened when no improvement is apparent.

Cresty neck score is also less reliable as the crest contains a large amount of fibrous tissue that will remain, even with marked loss of adipose tissue.

It is important to find markers that provide owners with gratification, and heart and belly girth are, therefore, the most suitable. It is also important to consider regular veterinary check-ins to ensure that the weight loss is going according to plan and allow any necessary adjustments to be made based.

Targets are helpful and provide a sense of purpose, so it is useful to provide charts to monitor morphometric characteristics and bodyweight. Targets for exercise based on working towards the owner’s aspirations (for example, to get the horse fit enough to enter a sponsored ride or undertake a specific activity) are also a powerful motivator1. Utilising apps that allow exercise targets to be set and progress to be tracked can also be helpful.

In horses with weight loss resistance, a further forage restriction to 1% BM as DMI or 1.15% BM as fed may be considered if appropriately monitored. However, it is preferable not to decrease forage provision to less than 1% of target bodyweight as this may increase the risk for hindgut dysfunction, stereotypical behaviours, ingestion of bedding or coprophagy.

Once the target weight is achieved, it is important that monitoring of weight by the owner is continued, or experience from other species indicates that diet and management changes will not be maintained in a large proportion of cases, and many will return to an obese state.

Equids that have lost weight may still exhibit ID and, if they do, should continue to be fed low sugar/starch (less than 10% to 12% NSC) feeds that will limit the glycaemic and, therefore, insulinaemic response.

A high-fibre, low-cereal diet will be healthier, so any return to feeding cereals after weight has been lost should be discouraged. Any subsequent gain in weight, however transient, may be associated with decreased insulin sensitivity and, therefore, increased laminitis risk.

References

- Rendle DI et al (2018). Equine obesity: current perspectives, UK-Vet Equine 2(Suppl 5): 1-19.

- Robin CA et al (2015). Prevalence of and risk factors for equine obesity in Great Britain based on owner-reported body condition scores, Equine Vet J 47(2): 196-201.

- Potter SJ et al (2016). Prevalence of obesity and owners’ perceptions of body condition in pleasure horses and ponies in south-eastern Australia, Aust Vet J 94(11): 427-432.

- Dugdale AH et al (2011). Assessment of body fat in the pony: part II. Validation of the deuterium oxide dilution technique for the measurement of body fat, Equine Vet J 43(5): 562-570.

- Dugdale AH et al (2012). Body condition scoring as a predictor of body fat in horses and ponies, Vet J 194(2): 173-178.

- Carroll CL and Huntington PJ (1988). Body condition scoring and weight estimation of horses, Equine Vet J 20(1): 41-45.

- Carter RA et al (2009). Apparent adiposity assessed by standardised scoring systems and morphometric measurements in horses and ponies, Vet J 179(2): 204-210.

- Ferjak EN et al (2017). Body fat of stock-type horses predicted by rump fat thickness and deuterium oxide dilution and validated by near-infrared spectroscopy of dissected tissues, J Anim Sci 95(10): 4,344-4,351.

- Britchett KB et al (2017). Use of ultrasonography to evaluate the accuracy of objective and subjective measures of body composition in horses, J Anim Sci 94(1): 16.

- Menzies-Gow NJ et al (2017). Prospective cohort study evaluating risk factors for the development of pasture-associated laminitis in the United Kingdom, Equine Vet J 49(3): 300-306.

- Dosi MCM et al (2020). Inducing weight loss in native ponies: is straw a viable alternative to hay? Vet Rec 187(8): e60.

- Carslake HB et al (2018). Insulinaemic and glycaemic responses to three forages in ponies, Vet J 235: 83-89.

- Durham AE et al (2019). ECEIM consensus statement on equine metabolic syndrome, J Vet Intern Med 33(2): 335-349.

- Moore JL et al (2019). Effects of diet versus exercise on morphometric measurements, blood hormone concentrations, and oral sugar test response in obese horses, J Equine Vet Sci 78: 38-45.

- Frank N et al (2008). Effects of long-term oral administration of levothyroxine sodium on glucose dynamics in healthy adult horses, Am J Vet Res 69(1): 76-81.