25 Aug 2020

Poorly performing equids: lameness causes, treatment and prevention

Mélanie Perrier discusses the conditions associated with this issue, as well as the need for a multimodal strategy to manage cases.

Poor performance evaluation can be a challenging and recurring source of frustration for all parties involved. Very often, subtle lameness causing some variation in a horse’s ridden abilities – such as reluctance to go forward, getting disunited and not willing to bend – may be the only recognisable clinical signs.

A thorough physical examination, followed by lameness and ridden examinations, is usually warranted. The lameness examination may be complicated by the presence of more than one source of lameness, the presence of a bilateral lameness that makes the diagnosis less obvious and other non-musculoskeletal factors.

Locoregional and intra-articular anaesthesia should be performed when possible, and correlated to the main complaint, clinical signs – including palpation – and diagnostic imaging to obtain as precise a diagnosis as possible. Once a diagnosis has been obtained, a proper treatment plan should be discussed with the owner and an adequate rehabilitation protocol put in place.

This article will give an overview of some selected common causes of lameness associated with poor performance and some selected common treatments used for these conditions. It will then briefly go over some rehabilitation modalities that could be used both for the treatment of poor performance cases and in their prevention, as it is believed to be an important part of managing these cases.

Poor performance evaluation can be a challenging and recurring source of frustration for all parties involved.

As for most cases, obtaining a thorough history is of particular importance. When possible, establishing objective measurements of the horse’s performance (Hobbs et al, 2020) or the lack thereof – taking into account the complexity of the horse/rider partnership – should be favoured.

Identifying those measurements will vary depending on the discipline the horse is performing in, and could include performance records, looking at scores awarded by judges for dressage horses, race earnings, and watching video recordings of good and poor prior performances. When no objective measurements are available, evaluating rider ability/expectation versus horse ability may add another degree of complexity.

A complete physical examination should be performed as other causes – including respiratory and cardiovascular pathology – may be responsible for poor performance. Evaluation of the horse’s training regimen – intended use taking into account training surfaces, conformation and lameness examination, followed by evaluation of the horse and rider as a team – should be performed.

In some cases, evaluation of the horse with the tack on before putting any weight on may be beneficial, together with using a different rider then normal (Video 1).

In other cases, where the safety of the rider may be compromised by the horse’s clinical signs, the use of a weighted saddle may be considered (Video 2).

For consistent lameness, diagnostic anaesthesia should be performed and carefully interpreted.

The usefulness of objective gait analysis (van Weeren and Gómez Álvarez, 2019; Gómez Álvarez and van Weeren, 2019) has been questioned in diagnosing poor performance, but may have value in evaluating the training and exercise programme; some systems have the added advantage of back sensors that could, in the future, be helpful in further assessing back movement (Figure 1).

Once the region of the lameness has been narrowed down by history, clinical examination, palpation and the use of diagnostic anaesthesia, further diagnostics should be performed to obtain a definite diagnosis and put in place an appropriate treatment plan.

In cases where the aforementioned diagnostics did not help find a cause, nuclear scintigraphy may be useful to rule out certain conditions or highlight pathologies difficult to diagnose by palpation and local anaesthetic techniques, such as stress fractures and certain osseous cyst-like lesions (Dyson, 2016a; 2016b).

Lameness conditions associated with poor performance

Poor performance can be associated with a wide array of conditions (Dyson, 2002) – including derangement in muscle function (Valberg, 2018), OA, affection of tendons and ligaments, sacroiliac disease and back pathology – and predisposition may vary according to the age, breed and use of the horse.

Similarly, clinical presentations may vary greatly between pathology and specific cases; some may present as lameness, while others may show more discrete signs, such as reluctance to go forward, getting disunited, not willing to bend and resisting the bit.

It is not unusual for more than one pathology to be present and this should be taken into consideration when evaluating cases. For example, bilateral hindlimb suspensory desmitis may be related to sacroiliac pain; thoracolumbar pain could also be associated with an underlying lameness and an aggravating factor to poor performance; and hindlimb origin of the suspensory desmitis and tarsal pathology may be concurrent.

Muscle dysfunction and pain can affect gait and performance. Conditions such as bruising, strain, poor saddle fit and exertional myopathies may be responsible for poor performance in the form of exercise intolerance, reluctance to go forward and difficulty to collect.

Diagnosis can be challenging and could include a complete physical examination; measurement of creatinine kinase and aspartate aminotransferase, at rest and after exercise; electromyography; and muscle biopsy.

Foot pain associated with, for example, foot imbalance, navicular disease and bruising is a common cause of lameness in horses, regardless of the discipline they train in (Gutierrez-Nibeyro et al, 2010). When no obvious unilateral lameness results from this condition, a bilateral palmar digital nerve block could be performed – and the horse evaluated ridden both before and after the block – to see whether an improvement is noted by the rider. MRI (Dyson et al, 2003) is a useful tool – in addition to radiographs – to diagnose feet problems in horses and should be considered in cases without radiographic abnormalities or those that show poor response to medical treatment.

Degenerative joint disease is another well‑documented cause of lameness and/or poor performance in competition horses, and can affect any high-motion or low-motion joint. Depending on the discipline, the distal phalanges or metacarpophalangeal/metatarsophalangeal joints – together with the distal tarsal joints – are a common location for the pathology. These cases normally respond well to intra‑articular anaesthesia and changes may be seen on radiographs. MRI may also be helpful in selected cases.

Suspensory ligament injuries are also often reported as a cause of lameness and poor performance in competing horses. Diagnosing suspensory pathology should involve a thorough clinical examination, including palpation of the area, lameness evaluation, diagnostic anaesthesia and diagnostic imaging.

One challenge is that diagnostic anaesthesia may not be specific, especially when considering hindlimb origin of the suspensory desmitis. In that region, positive diagnostic anaesthesia can also refer to pain in the tarsal region.

Similarly, subclinical ultrasonographic changes of suspensory ligament branches have been reported in regularly competing elite showjumpers, prompting judicious interpretation (Read et al, 2020).

Therefore, a combination of diagnostic tools is often needed – including separate intra‑articular anaesthesia of the tarsometatarsal or distal intertarsal joints, radiographs (tarsal arthritis and changes over the proximal metatarsal/metacarpal bone), ultrasound of the suspensory ligament, nuclear scintigraphy and potential MRI (Lischer et al, 2006a).

Pathology of the axial skeleton – including the neck, back and pelvic regions – have been reported in horses presented for evaluation of poor performance (García-López, 2018).

Back pain can have a wide range of clinical presentations – varying from pain on palpation of the region, stiffness, lameness, bucking under saddle, the horse unwilling to go forward, and getting disunited.

Equine back disorders can be primary or secondary, and may be challenging to diagnose as it can be associated with soft tissue injuries and vertebral lesions, but also tack‑associated problems, poor riding abilities and, less commonly, neurological lesions. Common conditions include overriding spinous processes, supraspinous desmitis and OA of the intervertebral facets.

Radiography alone is not representative of active inflammation and it is better evaluated in conjunction with scintigraphy (Zimmerman et al, 2012), ultrasound, clinical signs and palpation/evaluation of the region. Diagnostic anaesthesia may be a complimentary tool in certain cases.

Commonly, an area of suspicion for the origin of the pain will have to be identified – either by palpation or diagnostic imaging – to be locally infiltrated with local anaesthetic. Again, a ridden examination can be performed before and after diagnostic anaesthesia to evaluate the response (Videos 1 to 3).

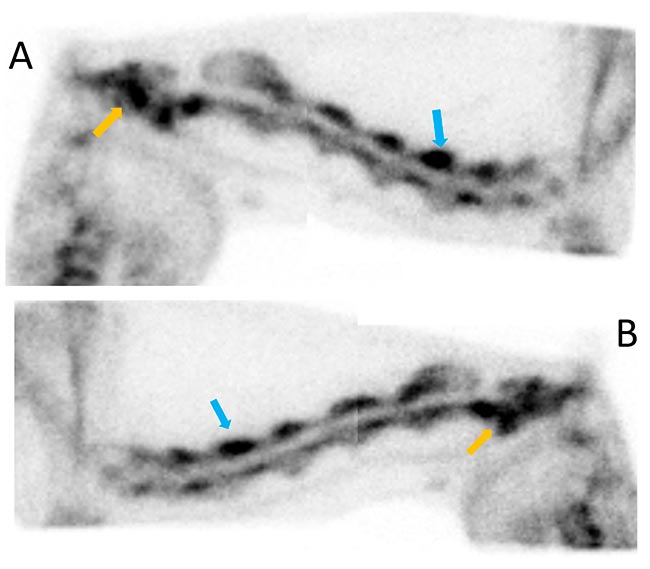

Neck problems may present as refusing to jump, difficulty to bend and collect, and even neurological signs. Cervical pathology that may impact the horse’s performance include – but aren’t limited to – nuchal bursitis and intervertebral facet joint OA. Similarly, diagnosis will be based on clinical signs, palpation, ultrasound, radiographs, CT and/or nuclear scintigraphy (Figure 2).

Sacroiliac problems can also present with various clinical signs that are usually not specific (Dyson and Murray, 2003; Lorenz and Brounts, 2012; Goff et al, 2008). Signs can include pain on palpation of the area, poor hindquarter mobilisation, getting disunited and bucking under saddle.

Local anaesthesia of the sacroiliac region may be performed; however, care should be taken due to the proximity of the femoral and sciatic nerve, and potential associated complications with the block. Alternatively, transrectal ultrasound of the region (Tomlinson et al, 2003), nuclear scintigraphy (Gorgas et al, 2009) and trial medication of the area could be used to aid in diagnosing sacroiliac issues.

Treatment and prevention

Once a cause for the lameness/poor performance is established, an appropriate treatment plan should be put into place. It is very important to have as complete and accurate a diagnosis as possible to implement an effective treatment strategy.

For degenerative joint disease (McIlwraith, 1982; McIlwraith and Vachon, 1988; Contino, 2018), this will usually consist of medication of the affected area with steroids (McIlwraith and Lattermann, 2019), a combination of steroids and hyaluronic acid, polysulfated glycosaminoglycans, polyacrylamide hydrogel or biologics (Magri et al, 2019).

Back, neck and sacroiliac pathology – and some cases of suspensory desmitis – may benefit from corticosteroid injection (Marks, 1999).

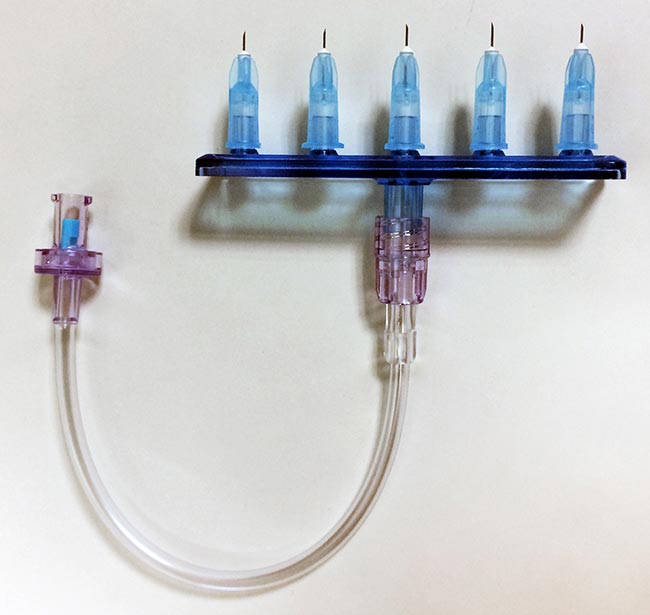

Mesotherapy (Figure 3; Video 4) is also a good alternative to treating back and neck problems in the horse (Alves et al, 2018). Tiludronic acid has been shown to be useful in improving dorsal flexibility in horses affected with arthritis of the thoracolumbar region.

The use of biological treatment – including stem cells, platelet-rich plasma and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein – have also been described, but the scientific evidence remains scarce and is usually clinician-guided (Ortved, 2018).

Shockwave therapy can be used in the treatment of suspensory ligament desmitis (Giunta et al, 2019; Lischer et al, 2006b; Crowe et al, 2004) and back pain (Trager et al, 2020). Its use in the treatment of sacroiliac pain – and over low-motion joints and the navicular region – is also described.

Surgical treatments are often limited, but may include neurectomy of the lateral plantar nerve and fasciotomy for the treatment – of hindlimb origin – of the suspensory ligament desmitis (Dyson and Murray, 2012; Bathe, 2006; Hewes and White, 2006), desmotomy of the interspinous ligament (Derham et al, 2019; Coomer et al, 2012) or ostectomies of the affected overriding processes (Jacklin et al, 2014; Brink, 2014). An adequate rehabilitation programme should also be performed following surgery.

Adequate foot balance is also an important part of the treatment and should be provided depending on the diagnosis (Balch, 2007).

Preventive measures rely on frequent and reasoned evaluation – and re-evaluation – of the patients. This may include evaluation at the beginning of the season, then at regular intervals to assess changes in the horse’s lameness/performance ability. Great cooperation between rider, groom, veterinarian, physiotherapist, farrier and other supportive personnel is needed at all times.

A detailed rehabilitation programme should be added to the treatment modality chosen (McGowan and Cottriall, 2016; Kaneps, 2016); it should be established as soon as possible and tailored to each individual, ideally with the involvement of a certified equine physiotherapist and chiropractor.

Another challenge in the management of the poorly performing equid is the lack of evidence-based criteria for rehabilitation and the variability in treatment protocol. Unfortunately, no one treatment fits, and regular assessment of progress and exercise adjustment will be necessary. This may involve extensive commitment and compliance from the rider.

Programmes involving the incorporation of lungeing with training aids (Video 5), daily stretching, joint manipulation, core activation (Clayton, 2016), proprioceptive rehabilitation and regular chiropractic/acupuncture sessions may improve the outcome in poor performance cases, and can be used as a preventive measure if performed correctly and adequately (Haussler, 2010; 2016; 2018; Porter, 2005).

Thermal therapy can be useful in selected cases (Kaneps, 2016). Cold therapy is usually preferred in acute cases to reduce inflammation, but can also be used for pain reduction. Heat is usually preferred for chronic injuries, and can be provided through warm water, hot packs and therapeutic ultrasound.

The use of kinesiology tape has been reported to stimulate the proprioceptive sensory pathway, leading to possible modulation of locomotor function and range of motion (Molle, 2016; Ramón et al, 2004). Again, very little scientific evidence exists as to its efficiency (Ericson et al, 2020), but equally, no scientific evidence exists proving with certainty that it does not work.

Hydrotherapy (King, 2016) can be an efficient tool, both in the treatment period for certain injuries where overloading of the area should be avoided, but also as a maintenance tool to improve musculoskeletal and cardiovascular function; it has also been proved to be an efficient medium to improve joint mobility. Various modalities are available, such as underwater treadmills and swimming pools.

Laser therapy and electrical therapies (Duesterdieck-Zellmer et al, 2016; Schlachter and Lewis, 2016) can be incorporated to the rehabilitation regimen to decrease inflammation and pain perception. Regular sessions may initially be required (every other day/three times weekly), but can progressively be adjusted pending on response to treatment to once a week and, ultimately, once a month.

Conclusion

Cases of poor performance can be challenging and may involve more than one cause. A multimodal approach to treatment and prevention is an important part of managing these cases.

A lot of research still needs to be done in the ever-growing area of equine poor performance. Cooperation between all parties involved remains key to optimal results, as frequent reassessment and readjustments of therapies is often needed due to the limited scientific evidence as to which protocol to use and when.

References

- Alves JC, Dos Santos AM and Fernandes ÂD (2018). Evaluation of the effect of mesotherapy in the management of back pain in police working dog, Vet Anaesth Analg 45(1): 123-128.

- Balch OK (2007). Discipline-specific hoof preparation and shoeing, Equine Podiatry, Saunders, Philadelphia: 393-413.

- Bathe AP (2006). Plantar metatarsal neurectomy and fasciotomy for the treatment of hindlimb proximal suspensory desmitis, Proc BEVA Congress, Birmingham: 198-199.

- Brink P (2014). Subtotal ostectomy of impinging dorsal spinous processes in 23 standing horses, Vet Surg 43(1): 95-98.

- Clayton HM (2016). Core training and rehabilitation in horses, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 49-71.

- Contino EK (2018). Management and rehabilitation of joint disease in sport horses, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 34(2): 345-358.

- Coomer RPC, McKane SA, Smith N and Vandeweerd JME (2012). A controlled study evaluating a novel surgical treatment for kissing spines in standing sedated horses, Vet Surg 41(7): 890-897.

- Crowe OM, Dyson SJ, Wright IM, Shramme MC and Smith RKW (2004). Treatment of chronic or recurrent proximal suspensory desmitis using radial pressure wave therapy, Equine Vet J 36(4): 313-316.

- Derham AM, O’Leary JM, Connolly SE, Schumacher J and Kelly G (2019). Performance comparison of 159 Thoroughbred racehorses and matched cohorts before and after desmotomy of the interspinous ligament, Vet J 249: 16-23.

- Duesterdieck-Zellmer KF, Larson MK, Plant TK, Sundholm‑Tepper A and Payton ME (2016). Ex vivo penetration of low-level laser light through equine skin and flexor tendons, Am J Vet Res 77(9): 991-999.

- Dyson S (2002). Lameness and poor performance in the sport horse: dressage, show jumping and horse trials, J Equine Vet Sci 22(4): 145-150.

- Dyson S (2016a). Evaluation of poor performance in competition horses: a musculoskeletal perspective. Part 1: clinical assessment, Equine Vet J 28(5): 284-293.

- Dyson S (2016b). Evaluation of poor performance in competition horses: a musculoskeletal perspective. Part 2: further investigation, Equine Vet J 28(7): 379-387.

- Dyson S and Murray R (2003). Pain associated with the sacroiliac joint region: a clinical study of 74 horses, Equine Vet J 35(3): 240-245.

- Dyson S and Murray R (2012). Management of hindlimb proximal suspensory desmopathy by neurectomy of the deep branch of the lateral plantar nerve and plantar fasciotomy: 155 horses (2003-2008), Equine Vet J 44(3): 361-367.

- Dyson S, Murray R, Schramme M and Branch M (2003). Magnetic resonance imaging of the equine foot: 15 horses, Equine Vet J 35(1): 18-26.

- Ericson C, Stenfeldt P, Hardeman A and Jacobson I (2020). The effect of kinesiotape on flexion-extension of the thoracolumbar back in horses at trot, Animals 10(2): 301.

- García-López JM (2018). Neck, back, and pelvic pain in sport horses, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 34(2): 235-251.

- Giunta K, Donnell JR, Donnell AD and Frisbie DD (2019). Prospective randomized comparison of platelet rich plasma to extracorporeal shockwave therapy for treatment of proximal suspensory pain in western performance horses, Res Vet Sci 126: 38-44.

- Goff LM, Jeffcott LB, Jasiewicz J and McGowan CM (2008). Structural and biomechanical aspects of equine sacroiliac joint function and their relationship to clinical disease, Vet J 176(3): 281-293.

- Gómez Álvarez CB and van Weeren PR (2019). Practical uses of quantitative gait analysis in horses, Equine Vet J 51(6): 811-812.

- Gorgas D, Luder P, Lang J, Doherr MG, Ueltschi G and Kircher P (2009). Scintigraphic and radiographic appearance of the sacroiliac region in horses with gait abnormalities or poor performance, Vet Radiol Ultrasound 50(2): 208-214.

- Gutierrez-Nibeyro SD, White NA and Werpy NM (2010). Outcome of medical treatment for horses with foot pain: 56 cases, Equine Vet J 42(8): 680-685.

- Haussler KK (2010). The role of manual therapies in equine pain management, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 26(3): 579-601.

- Haussler KK (2016). Joint mobilization and manipulation for the equine athlete, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 87-101.

- Haussler KK (2018). Equine manual therapies in sport horse practice, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 34(2): 375-389.

- Hewes CA and White NA (2006). Outcome of desmoplasty and fasciotomy for desmitis involving the origin of the suspensory ligament in horses: 27 cases (1995-2004), J Am Vet Med Assoc 229(3): 407-412.

- Hobbs SJ, St George L, Reed J, Stockley R, Thetford C, Sinclair J, Williams J, Nankervis K and Clayton HM (2020). A scoping review of determinants of performance in dressage, PeerJ 8: e9022.

- Jacklin BD, Minshall GJ and Wright IM (2014). A new technique for subtotal (cranial wedge) ostectomy in the treatment of impinging/overriding spinous processes: description of technique and outcome of 25 cases, Equine Vet J 46(3): 339-344.

- Kaneps AJ (2016). Practical rehabilitation and physical therapy for the general equine practitioner, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 167-180.

- King MR (2016). Principles and application of hydrotherapy for equine athletes, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 115-126.

- Lischer CJ, Bischofberger AS, Fürst A, Lang J and Ueltschi G (2006a). Disorders of the origin of the suspensory ligament in the horse: a diagnostic challenge, Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 148(2): 86-97.

- Lischer CJ, Ringer SK, Schnewlin M, Imboden I, Fürst A, Stöckli M and Auer J (2006b). Treatment of chronic proximal suspensory desmitis in horses using focused electrohydraulic shockwave therapy, Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 148(10): 561-568.

- Lorenz J and Brounts SH (2012). Sacroiliac injuries in horses, Compend Contin Educ Vet 34(11): E3.

- Marks D (1999). Medical management of back pain, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 15(1): 179-194.

- Magri C, Schramme M, Febre M, Cauvin E, Labadie F, Saulnier N, François I, Lechartier A, Aebischer D, Moncelet AS and Maddens S (2019). Comparison of efficacy and safety of single versus repeated intra‑articular injection of allogeneic neonatal mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of osteoarthritis of the metacarpophalangeal/metatarsophalangeal joint in horses: a clinical pilot study, PLoS One 14(8): e0221317.

- McGowan CM and Cottriall S (2016). Introduction to equine physical therapy and rehabilitation, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 1-12.

- McIlwraith CW (1982). Current concepts in equine degenerative joint disease, J Am Vet Med Assoc 180(3): 239-250.

- McIlwraith CW and Lattermann C (2019). Intra-articular corticosteroids for knee pain – what have we learned from the equine athlete and current best practice, J Knee Surg 32(1): 9-25.

- McIlwraith CW and Vachon A (1988). Review of pathogenesis and treatment of degenerative joint disease, Equine Vet J 20(S6): 3-11.

- Molle S (2016). Kinesio taping fundamentals for the equine athlete, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 103-113.

- Ortved KF (2018). Regenerative medicine and rehabilitation for tendinous and ligamentous injuries in sport horses, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 34(2): 359-373.

- Porter M (2005). Equine rehabilitation therapy for joint disease, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 21(3): 599-607.

- Ramón T, Prades M, Armengou L, Lanovaz JL, Mullineaux DR and Clayton HM (2004). Effects of athletic taping of the fetlock on distal limb mechanics, Equine Vet J 36(8): 764-768.

- Read RM, Boys-Smith S and Bathe AP (2020). Subclinical ultrasonographic abnormalities of the suspensory ligament branches are common in elite showjumping Warmblood horses, Front Vet Sci 7: 117.

- Schlachter C and Lewis C (2016). Electrophysical therapies for the equine athlete, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 32(1): 127-147.

- Tomlinson JE, Sage AM and Turner TA (2003). Ultrasonographic abnormalities detected in the sacroiliac area in twenty cases of upper hindlimb lameness, Equine Vet J 35(1): 48-54.

- Trager LR, Funk RA, Clapp KS, Dahlgren LA, Werre SR, Hodgson DR and Pleasant RS (2020). Extracorporeal shockwave therapy raises mechanical nociceptive threshold in horses with thoracolumbar pain, Equine Vet J 52(2): 250-257.

- Valberg SJ (2018). Muscle conditions affecting sport horses, Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 34(2): 253-276.

- Van Weeren PR and Gómez Álvarez CB (2019). Equine gait analysis: the slow start, the recent breakthroughs and the sky as the limit?, Equine Vet J 51(6): 809-810.

- Zimmerman M, Dyson S and Murray R (2012). Close, impinging and overriding spinous processes in the thoracolumbar spine: the relationship between radiological and scintigraphic findings and clinical signs, Equine Vet J 44(2): 178-184.