28 Oct 2025

Practical approaches to equine vaccination and parasite control

Fleur Whitlock BVetMed, MSc, MRCVS Richard Newton BVSc, MSc, PhD, FRCVS and Philip Ivens MA, DipECEIM, VetMB, CertEM(IntMed), DipECEIM, MRCVS discuss how vets are perfectly placed to lead the process of prioritising proactive strategies to better safeguard horses.

Image: encierro / Adobe Stock

Infectious diseases and parasite burdens compromise equine health, welfare and performance, while also placing considerable financial and emotional strain on owners.

The landscape for effective parasite control is continually evolving, driven by the need to respond to emerging anthelmintic resistance and the changing risks associated with climate change. At the same time, endemic infectious diseases, such as equine influenza (EI), strangles and equine herpes virus, remain ever present, while the possibility of novel disease incursions, such as West Nile virus (WNV), is a constant concern.

By prioritising proactive, evidence-based preventive strategies, we can reduce reliance on emergency interventions and better safeguard the health of both individual horses and the wider equine population.

Equine vets are uniquely positioned to lead this process. As trusted health advisors, their knowledge of local disease risks, yard layout, horse demographics and management practices enables the design of tailored yard health plans that are both practical, but evidence based. These plans should be considered “living documents”, and as such are reviewed regularly and adapted to reflect changes in risk or management practices.

Developing and implementing such plans collaboratively with owners strengthens compliance, promotes long-term trust and reinforces the vet’s central role in maintaining equine health at both individual and premises level. Vaccination and parasite control remain central to yard-wide health plans and should be embedded within a broader framework encompassing all aspects of equine care and management.

This article provides a practical overview of vaccination and parasite control for UK horse populations, with a focus on timing, protocols, owner communication and their inclusion in effective yard health plans.

Due to the broad range of equine premises that require such preventive health planning, this article provides overarching principles rather than specific health plan details.

Incorporation of vaccination into equine premises health planning

Vaccination remains one of the most effective tools in preventive equine health management, although it should not be relied upon in isolation.

Vaccination should be integrated with premises-specific risk assessments to identify management practices that increase the likelihood of disease incursion and spread. These high-risk areas can then be reinforced with additional biosecurity measures.

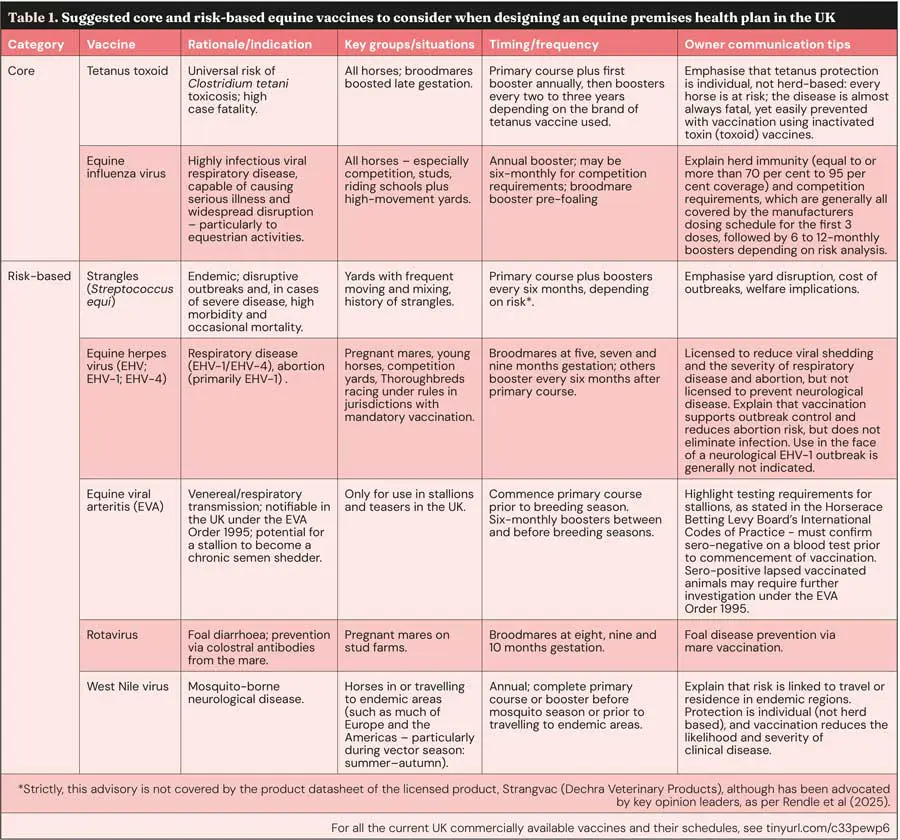

Core vaccines can be defined as those recommended for all horses regardless of age, type or use. EI vaccination is critical at the population level – particularly given the ever-evolving differences between circulating EI virus strains and those represented in vaccines, which raises the potential for future vaccine failure.

Population medicine plays a key role in preventing disease spread, and the success of EI vaccination relies on achieving sufficient population immunity – estimated at a minimum of 70% of horses on a premises, but potentially rising to 95% if antigenic changes in EI virus strains occur.

If only a subset of horses on a premises are vaccinated while others remain fully susceptible, those unvaccinated horses may shed high levels of virus if infected. This increased viral load can overwhelm the protection threshold of vaccinated in-contact horses, as demonstrated in both experimental and field studies.

Alongside influenza, tetanus vaccination is essential for every horse as a fatal disease, but from which vaccination provides excellent protection. Several risk-based vaccines may be appropriate depending on specific premises’ circumstances. These include vaccines for strangles (in all contexts), equine herpes virus (EHV-1 and EHV-4), equine viral arteritis, rotavirus (these three especially in breeding contexts) and WNV (where travel or geographic risk dictates; Table 1).

The decision whether to use these vaccines should take into account the premises risk, including horses’ movements, population demographics, and the owner’s breeding or competition goals.

Raising awareness of current disease surveillance reports and local outbreak risks can be a powerful motivator for vaccination uptake. Clear communication around the individual and population-level benefits of vaccination also helps to address vaccine hesitancy, which may stem from misconceptions about safety, cost and necessity. Veterinary practices can use a range of client communication methods to reinforce key messages, from tailored discussions during routine visits to newsletters, social media updates and client evenings. Practical tools such as calendar reminders can further support compliance, ensuring that protection is maintained consistently across the yard.

In addition, engaging yard owners or managers to establish and enforce vaccination requirements across the yard population provides a valuable opportunity to normalise preventive health planning and strengthen overall disease resilience.

Incorporation of endoparasite control plans into yard health planning

Calendar-based deworming programmes, once routine, are now recognised as unsustainable. Frequent blanket dosing accelerates the development of anthelmintic resistance and risks leaving limited treatment options for the future.

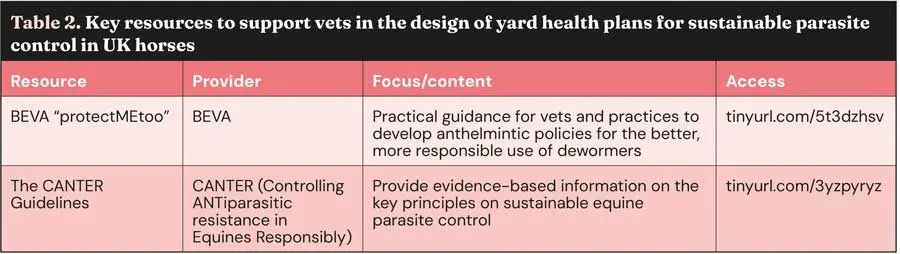

Instead, parasite control should be guided by evidence, with targeted approaches tailored to the yard and individual horses. Central to this is the use of faecal worm egg count tests (FWECs) to identify specific horses requiring anthelmintic treatment, alongside consideration of seasonal parasite dynamics and age-related risks (for example, youngstock versus adults).

Tests for tapeworm provide additional diagnostic support, enabling selective treatment and reducing unnecessary drug use.

Preserving the efficacy of available anthelmintics is a critical priority. Resistance to anthelmintics is already widespread in cyathostomins and increasingly recognised in ascarids and pinworms, underlining the need for veterinary leadership in designing, implementing and monitoring worming strategies in conjunction with non-chemical approaches, which are equally important.

Pasture hygiene measures, such as regular poo picking, applying appropriate stocking densities, and using rotational or mixed-species grazing, form part of an integrated endoparasite control toolkit. By combining diagnostics, strategic treatments and management practices within a premises-wide plan, vets can deliver sustainable parasite control, better safeguard horse health and prolong the effectiveness of available anthelmintics.

Protocols should be tailored to each premises and developed by vets in conjunction with owners, drawing wherever possible on evidence-based guidelines and recognised resources (Table 2).

Practical approaches to vaccination and endoparasite control

Integrating vaccination and endoparasite control strategies into a yard health plan begins with a structured assessment of the premises.

Key considerations include the number of horses, their age groups, patterns of movement on and off the premises, and, for parasite control especially, access to pasture. These factors influence both the risk of infectious disease introduction and the most appropriate requirements for parasite control. A useful next step is risk categorisation, grouping horses according to their infectious disease and parasite exposures; for example, broodmares, youngstock, competition horses and retired companions will each differ in their vaccination priorities and parasite risks.

Stratifying the population in this way allows protocols to be targeted, reducing unnecessary treatments while ensuring high-risk groups receive appropriate protection. Management of new arrivals is central to preventive planning for both infectious and parasite exposures.

Enforcing clear isolation procedures and establishing entry requirements (such as vaccination status, parasite testing, screening for strangles carriers) reduces the risk of new introductions of pathogens and parasites. Isolation times will vary depending on the risks identified, but would range between 14 to 28 days, with 21 days being often a good compromise if a varied number of risks is identified.

Plans should be documented as written protocols, reviewed annually and updated as and when required. Laminated checklists in tack rooms or feed stores can serve as visible reminders, while staff training ensures consistent implementation across the yard. Shared planning tools can play a major role in improving communication and compliance. A dedicated central record of vaccination, parasite control (including FWEC results) and premises-wide biosecurity measures would enable vets and owners to track progress together and adapt protocols as required.

Digital tools have the potential to transform how yard health plans are developed and implemented. Information on vaccination schedules, parasite testing, treatments and biosecurity measures is often scattered across paper records, yard notebooks, individual owner files or veterinary practice management systems, making it difficult to maintain an accurate, shared population-level overview.

A digital dashboard, accessible to vets, yard managers and owners (for their respective horses), would consolidate all preventive health data in one place, and be updated in real time and reviewed collectively. Such a system could integrate calendar reminders, laboratory screening test schedules and results, outbreak alerts, and checklists, creating a practical and transparent framework for decision making.

Developing user-friendly digital platforms tailored to equine practice would enhance communication, strengthen compliance and allow protocols to be adapted rapidly in response to new risks. For vets, this would provide an invaluable tool to support the design and delivery of robust, evidence-based yard health plans – particularly on premises where multiple vets from multiple practices are involved.

Owner communication: turning advice into action

Even the most carefully designed yard health plan will fail without effective owner engagement and ongoing compliance. Clear, consistent communication is, therefore, central to turning veterinary advice into meaningful action.

A common challenge lies in addressing misconceptions; for example, owners may feel vaccination is unnecessary if a horse “never leaves the yard”, or believe that “natural immunity is better”. These concerns should be met with empathy and clear explanation: disease can enter even closed herds via visitors, equipment, or horses on neighbouring premises, and while natural infection may stimulate immunity, it may do so at the cost of significant illness and welfare compromise.

Practical communication tools can further promote health plan uptake. These include reminder systems, simple charts and visual timelines that show when vaccinations and FWECs are due.

Advocating for yard plans which incorporate a biosecurity plan can be helpful as a reward for the yard’s and owners’ efforts, almost like a badge of honour; for example, see the British Horse Society’s Approved livery yard and Keeping Britain’s Horses Healthy schemes. Consistency of message by the veterinary team is also important; when all staff deliver the same key messages, advice carries greater authority and credibility. Building trust is equally vital, as owners are more likely to follow preventive plans when they feel their concerns are acknowledged – particularly around cost or the practicality of implementing measures. A collaborative tone, tailoring protocols to the specific needs of the premises and individual horses, reinforces partnership rather than prescription.

Finally, digital solutions such as shared calendars, yard WhatsApp groups or emerging equine health apps, should offer new opportunities to improve health plan compliance. These tools allow real-time updates, reminders and shared access to protocols, making preventive health planning more transparent and easier to follow.

By combining clear communication, empathy and practical tools, vets should be able to increase uptake and embed preventive strategies into everyday yard routines.

Conclusion

Effective equine health management relies on prevention, with vaccination and parasite control embedded within broader premises-wide plans. Core vaccines such as tetanus and influenza remain essential for all horses, while risk-based options should be tailored to specific populations.

Sustainable parasite control requires evidence-based strategies that balance results from diagnostic testing, targeted treatment and pasture management. Equine vets are central to this process, not only in delivering interventions, but also in acting as trusted advisors who translate knowledge into practical premises-specific strategies.

Success depends on consistent messaging from across the veterinary team, clear communication with owners and acknowledgement of cost and management constraints.

By combining evidence-based protocols with collaborative communication, vets can readily strengthen long-term client relationships, and be involved in embedding effective preventive equine health planning as standard practice, across a wide range of equine premises.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 43, Pages 6-10

References

- Rendle D et al (2025). Strangles vaccination: A current European perspective, Equine Vet Educ 37(2): 90-97.