6 Sept 2021

Sarah Stoneham discusses how advice can be tailored to increase effective and sustained weight loss, and improve horse welfare.

All weather grass free turnout areas are useful to “kick start” a weight loss programme.

Estimates of equine obesity in the UK vary between 27% and 72%, with “leisure horse and ponies”, native breeds and traditional cobs at a greater risk of being obese than their working counterparts.

In the UK, the “leisure horse” is now considered to make up around 60% of the equine population1.

This epidemic is one of the current most serious welfare concerns. In studies at research institutes and veterinary facilities, weight loss is relatively easy to achieve by restricting energy intake and, where appropriate, instituting an exercise programme.

However, when the horse or pony is at home it becomes a far more complex issue2.

To give nutritional advice that is understood and followed by the owner, and is effective at reducing weight, it is important to understand some of the difficulties owners face when implementing weight loss management for their horse.

Owners of leisure horses often see the horse as a companion and see ownership being like that of a dog or a cat – focusing on the relationship with the animal, quality time spent with it and taking care of it, rather than working the horse or using it for sport3.

Many of these owners are concerned if they restrict what they perceive as things their horse enjoys – such as, grass, bucket feed and treats – that it will compromise their relationship with the horse2. It is important to address these concerns.

Strategies such as encouraging owners to spend time grooming or massaging their horses – or if they are reluctant to ride, then spending time working the horses in hand, including pole work – are alternatives to strengthen their relationship with the horse without relying on food.

If treats create a stumbling block, either using some of their daily allocation of feed balancer or the addition of a small, grated carrot may provide an acceptable solution.

It is important to ensure the owner understands what the expected weight loss on the plan will be – aim for 0.5% to 1% bodyweight (BW) per week after the first couple of weeks. It helps owners to appreciate that the management changes must be sustainable as it takes several months, rather than weeks, to reach ideal BW in most cases.

Grazing can be one of the most challenging aspects of an obese patient’s diet to manage successfully.

Many leisure horses or ponies are kept on livery yards with limited options for managing grazing and forage. As a result of agricultural diversification, much of the livery yard grazing is on pastures developed to maximise nutrients provided by the grass for production animals, and unsuitable for most “leisure” horses and ponies.

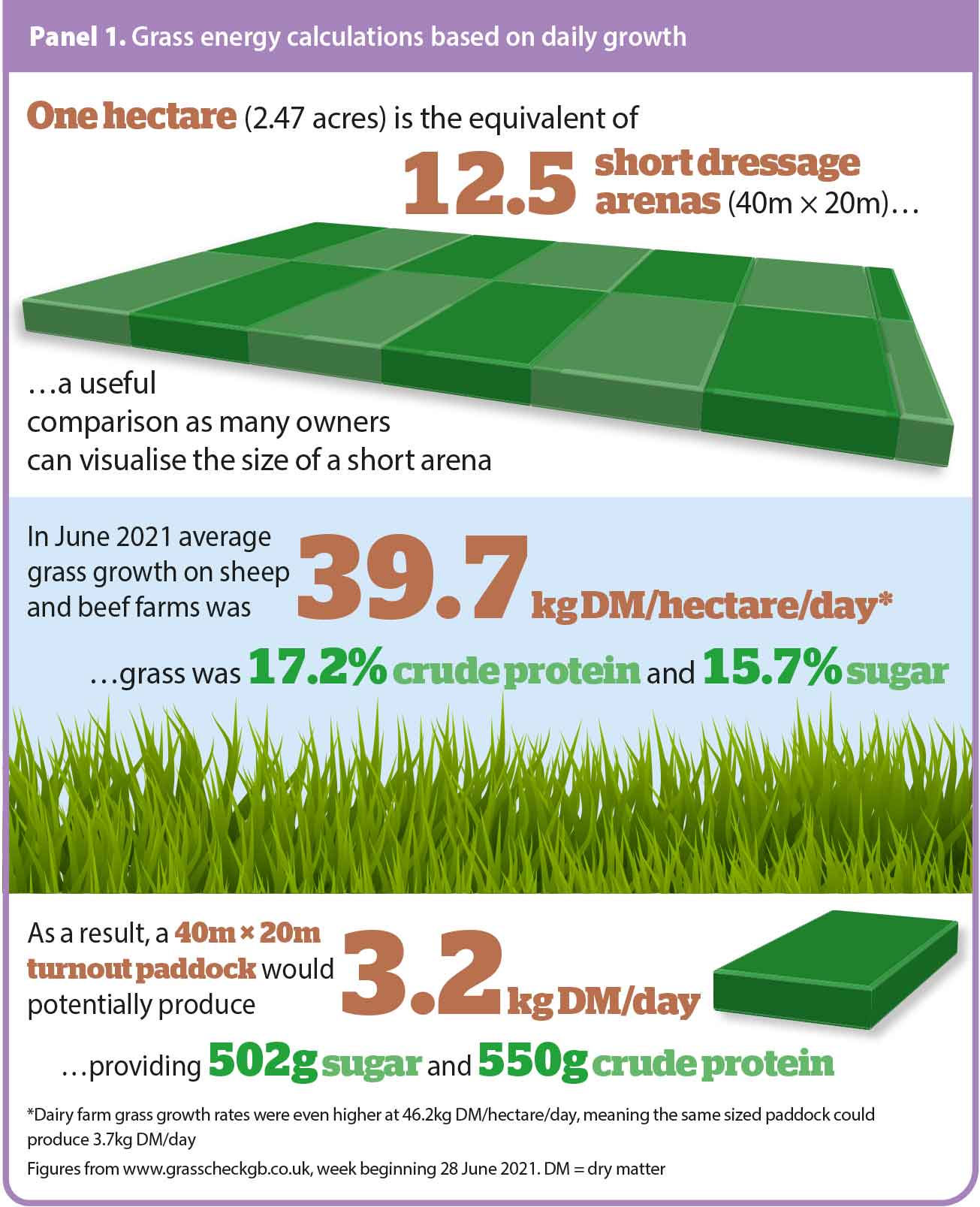

Many owners fail to appreciate the rate of grass growth during the spring, summer and early autumn. Several websites provide weekly average data for grass in the UK. The author has found that making a few simple calculations based on daily grass growth data in the UK can highlight just how much grass is available – even on small areas (Panel 1).

It is well established that ponies on regular time‑restricted grazing can consume up to 0.8% BW of grass on a dry matter (DM) basis in a 3-hour period4, leaving just 0.7% BW for the remaining 21 hours.

Many owners consider it safer to turn their ponies out overnight, rather than during the day. However, not only will overnight turnout usually be long, but also sugar levels in grass rise through the course of the day and only start to fall significantly in the early hours of the morning5.

Grazing from early in the morning until about 10am – a little later in cloudy weather – is more likely to coincide with lower sugar levels in the grass.

Strip grazing is often the only option for horses kept at livery yards. However, despite several methods and recommendations regarding strip grazing, only sparse scientific evidence exists on which method of strip grazing is most effective.

Longland et al6 have provided some useful evidence on different strip grazing methods for ponies. The study compared morphometric measurements and bodyweight changes of ponies using three different restricted grazing systems for 23 hours per day. The control group gained almost 5% BW and increased cresty neck score, belly girth and rump width over the 28-day study, whereas both groups of strip‑grazed ponies – either with just a lead fence moved daily or a lead and back fence – neither significantly lost or gained weight, or changed morphometric measurement.

Although the study confirmed strip grazing using either method will prevent significant weight gain, further studies are required to allow advice to be given on the best method of strip grazing for weight loss.

Grazing muzzles tend to polarise owners’ opinions; however, when correctly fitted they have been shown to reduce pasture intake by an average of 80%4.

Long swards make it more difficult to access the grass and can increase frustration – 10cm to 15cm swards are considered ideal.

Marked individual variation exists in how well the horse accepts and keeps a muzzle on. Careful introduction (see National Equine Welfare Council advice; Panel 2) and fitting, together with allowing access to a paddock with suitable sward height, will help increase the chance of the horse tolerating the muzzle. Different design works better with different individuals.

Before leaving horses turned out with a muzzle on, check they are drinking easily and not being bullied by their field companions.

A recent publication on alternative grazing systems in the UK provides useful information on systems being used by owners who are keen to keep their horses in a more natural environment providing the three Fs – forage, friends and freedom.

Track systems, Equicentral or woodland and moorland grazing were considered by owners to be most useful when horses needed to lose weight7. However, the system should be designed to limit the quantity of grass available on a daily basis to remove the potential for horses and ponies to initially consume excessive quantities of grass. However, these systems are more applicable when the land was owned by the horse owner.

Hopefully, more livery yards will develop grazing environments more suited to weight management.

Using a surfaced turnout pen or “dirt” sacrifice paddock, and providing suitable preserved forage, is often necessary in spring and autumn for obese ponies with severe insulin dysregulation (ID).

It can also be used successfully for several weeks to “kick-start” a weight loss programme and allow time for suitable longer‑term grazing arrangements to be made.

Providing suitable companions, and enriching the environment with logs, poles and scratch posts, can make this option more acceptable to some owners.

In the growing season, mowing a paddock to approximately 15cm and allowing it to be grazed no lower than 10cm can keep the grass in “regrowth” and lower water soluble carbohydrate (WSC) levels8.

Co-grazing with sheep or increasing equine stocking density, provided the horses are socially adapted, can reduce the available pasture.

It is well established that feeding hay is the most suitable option. This is supported by evidence that factors in haylage other than WSC may trigger an exaggerated insulinaemic response in ponies with ID when compared to response to hay with similar WSC levels9. The author also does not recommend soaking haylage.

Haylage tends to be more palatable and often has higher levels of digestible energy than hay. Most haylages are preserved by the exclusion of air, rather than the fermentation process that occurs with silage that leads to a significant fall in pH. When little or no fermentation has taken place, sugar levels will drop very little once it has been baled and wrapped.

In cases where no alternative to haylage is available, use of a low sugar/digestible energy (DE) commercial bagged haylage that has been analysed is the best option.

Hay analysis is recommended, as appearance is a poor guide to nutritional quality.

Wet chemistry is far superior and more reliable for analysis of WSC and non‑structural carbohydrate (NSC) levels in preserved forage. When dealing with horses that are overweight, look for low WSC (or sugars) – ideally less than 10% – and lower DE levels, around 8MJ/kg. If crude protein levels are low, the use of a feed balancer containing good-quality protein is recommended.

Many owners of leisure horses are only able to buy and store small, changeable batches of hay, making analysis impractical.

Few producers and suppliers of hay have nutritional analysis available. In these situations, recommend a late‑cut, meadow hay. Mature grass – indicated by a high stem to leaf ratio – is likely to be more appropriate.

The conditions in which the hay was made will influence sugar levels. To minimise sugar levels, hay cutting early in the morning (when sugar levels are naturally lower, provided it has not been too cold) and allowing to dry slowly (the cut grass will continue to respire and use sugars until moisture levels drop below 40%) is likely to achieve lower sugar levels10.

The lack of nutritional analysis of hay is the most common reason for recommending soaking hay.

It is well established that forage intake should be restricted to 1.5% BW per day on as-fed basis (this equates to approximately 1.25% BW on a DM basis). The author advocates using current BW, as ideal BW is difficult to predict accurately.

As the horse loses weight, the quantity of forage should be reduced accordingly. In cases of weight loss resistance – that is, when they fail to lose more than 1% bodyweight over a month – it may be necessary to reduce intake further1,11.

When intake is reduced to 1% BW, careful veterinary monitoring is recommended.

It is important to remember if haylage is used it will have a lower DM content, so intake needs to be adjusted accordingly.

To avoid cumulative weighing errors, the author recommends weighing the daily allowance of forage and then dividing into several small portions – the aim being that the horse doesn’t stand for more than four to five hours without anything to eat.

Soaking hay is a useful strategy to reduce WSC levels in hay, particularly when nutritional analysis is unavailable.

When hay is soaked, sugar – together with other nutrients – are leached into the surrounding water until levels equilibrate.

Many of the laboratory studies advocating short soaks are using large volumes of water for low weights of hay, such as 750g in 10L12, 50g in 4L10, 100g in 3L11 and 2kg in 24L13.

Short soak times reduce levels of microbial contamination, especially in warm weather, and can be more convenient for the owner, so when soaking for one hour ensure water volume is large – for example, a minimum of 25L of water for 2kg hay.

Other factors – such as temperature and how lignified the hay is – will affect reduction in WSCs.

Counter‑intuitively soaking hay reduces DM, so it will further restrict intake11. Increasing hay allowance to 1.8% BW per day has been recommended to compensate for this11.

Even soaking hay for 15 minutes has been shown to reduce essential amino acids12.

Straw has lower WSC and crude protein, and higher fibre and lignin levels than hay.

The higher lignin content increases “chew time” and reduces the digestibility.

For healthy ponies and cobs with good dentition and no history of impaction colic, adding straw can be useful, reducing overall energy density and WSC levels of the forage.

Straw should be good hygienic quality and free from cereal heads. It should be introduced slowly into the diet over a 10 to 14‑day period. Up to a third of the hay ration can be replaced with straw in many cases.

Dosi et al14 reported the success of feeding a 50:50 mixture of hay and straw to a group of ponies and horses kept out on pasture over winter, and supplemented with forage.

In some situations, owners are unable to source or store baled straw, in which case an unmolassed straw chop can be used. The author has used approximately 0.25kg/100kg BW/day fed damped in a bucket, or mixed through the hay or haylage, with some success.

Adjusting the bucket feed is much more straightforward than forage. However, owners’ choices and understanding of equine nutrition may be limited to advice from the owner’s social network, feed company marketing and limited personal experience.

Take a detailed history of what the owner is feeding the horse, including quantities, supplements and treats. This provides an ideal opportunity to emphasise the importance of feeding by weight, not volume, and the concept that percentage alone does not determine overall intake of a nutrient. Asking the owner to show you exactly what he or she is feeding – and a quick look at his or her feed room – is often enlightening.

When restricting forage and/or soaking hay, it is important to include a good‑quality feed balancer designed for horses and ponies on a restricted diet. The balancer should be fed in accordance with manufacturers’ recommended feeding rate – often 100g/100kg BW/day – to ensure provision of optimum levels of micronutrients and essential amino acids. Feed balancers with higher levels of good‑quality protein are more appropriate when restricted quantities of preserved forage with low crude protein levels are fed.

A high-fibre, low-calorie, unmolassed chop can be added to the bucket feed. This will increase chew time, which is useful for horses and ponies that have behavioural issues when other horses on the yard are being fed.

An alternative strategy to slow them down is to use a commercial slow feeder or by placing some large, flat, smooth river stones in their feed bucket.

A salt lick should be available 24/7 – and for those horses that do not use it or are sweating due to work or environmental temperatures, table salt should be added to their bucket feed.

To tailor advice, careful assessment of the horse’s management, environment and diet – together with the owner’s perception of what has triggered weight gain and the obstacle they see with weight loss management – will help you to advise an individualised, sustainable weight loss plan.

It is important to understand the nutritional options and evidence supporting them, so your dietary advice can be detailed rather than vague and generic.