19 Mar 2018

Preovulatory follicular stasis in a tortoise

Sonya Miles describes the case of a 75-year-old spur-thighed tortoise that presented with the reproductive condition.

Image: Alastair Rae / Wikimedia Commons.

A 75-year-old female spur-thighed tortoise (Testudo graeca) presented with a five-month history of anorexia since waking from hibernation.

On taking a clinical history, it became apparent the tortoise’s care, for decades, had been substandard, with no heat, UV light, calcium supplementation or adequate diet provided – it had been left in the garden only.

The tortoise had also never been bathed or provided with water, due to the owners’ misunderstanding tortoises get all the fluid they need from their diet. The tortoise had been allowed to dig itself into the garden and self-hibernate for excessive periods of time (often six to eight months), with no monitoring of weight or protection from elements or rodents.

During its years with the owners, the tortoise had been laying regularly. However, it had not passed any eggs for the past year, after its male companion died during its hibernation period.

On clinical examination, the tortoise had historical damage to its shell and forelimbs from rodents. It weighed 2.4kg, was obviously weak, oedematous at its prefemoral and pectoral windows, and unable to move unaided.

The tortoise was severely dehydrated, with sunken eyes that barely opened, but showed no sign of respiratory disease or stomatitis on examination.

The rest of its clinical examination was unremarkable. The owners were made aware of the poor prognosis, but allowed further investigations to be performed.

Supportive care

The tortoise was admitted for emergency hospitalisation, which involved placing it in a tortoise table set up to its preferred optimum temperature range using a radiant heat source (22°C to 24°C at the cool end and 32°C to 24°C at the basking end, with temperatures not dropping lower than 22°C at night). UV light of a suitable percentage (12%) was also provided. Regular bathing with a dietary support supplement was started (twice daily for 15 minutes) and 20ml/kg/day of IV fluids were provided, while investigations were performed and a clinical plan formed.

The tortoise was started on ceftazidime 20mg/kg, to be given every 72 hours IM for 8 consecutive doses prior to surgical intervention (and afterwards), and once it was warmed to its preferred optimal temperature.

Diagnostic procedures

Full biochemical and haematological profiles were performed by taking blood from the right jugular to avoid lymphatic dilution (often obtained when sampling from other sites). A full body CT scan was also performed. Blood tests revealed severe dehydration (but with normal renal function), signs of reproductive activity (increased albumin and calcium levels), a marked toxic heterophilia and monocytosis.

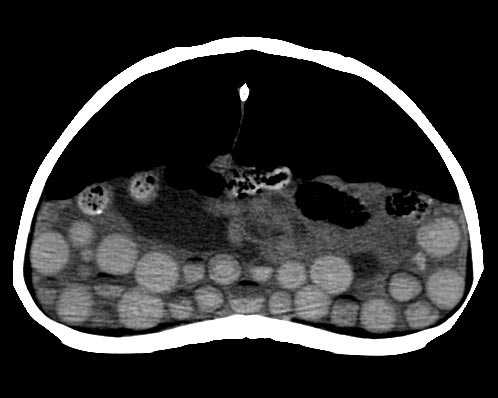

When analysing the CT scan, a very large number of abnormal follicles were noted in the coelomic cavity that were adhered to the liver and coelomic membrane in some sections. A large amount of fluid was also noted in some sections (Figure 1).

Due to the partially collapsed state, all tests were able to be performed conscious. The tortoise’s preferred optimum temperature was maintained and monitored with a digital thermometer throughout, particularly during the CT scan.

Surgery and treatment

In light of the blood and imaging results, a central plastron osteotomy was performed to allow access to the coelomic cavity, to perform an ovariectomy, as well as to allow in-depth assessment of the coelomic space and liver biopsies.

The tortoise was premedicated with 2mg/kg morphine IM, left for 60 minutes, then induced with alfaxalone 10mg/kg IV. The tortoise was intubated and ventilated to maintain anaesthesia using 3% to 5% sevoflurane in 2L/minute of oxygen.

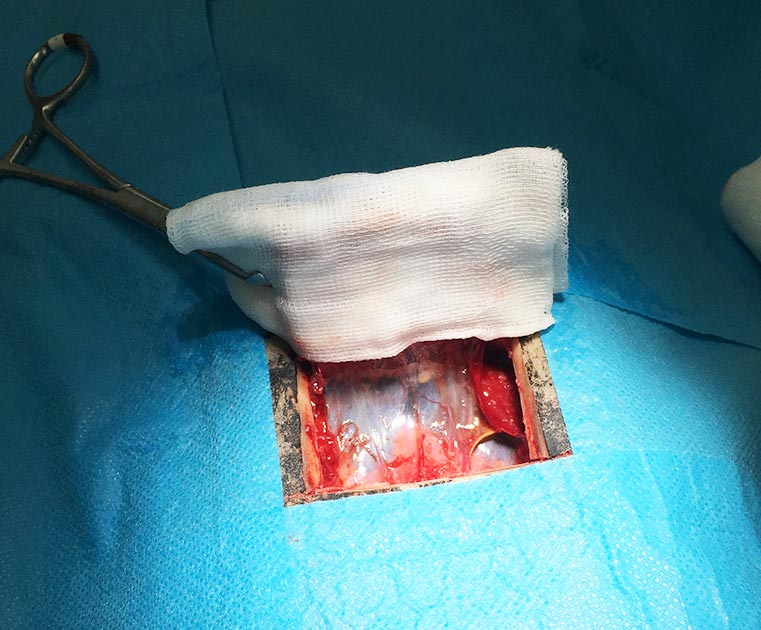

An oscillating hand saw was used to gain access through the shell, while small amounts of sterile saline were used to cool the blade during the cutting process. The flap of bone was cut at a bevelled angle on all four edges, with the inner aspect of the flap being smaller than the outside; this ensured the flap would not fall into the tortoise when replaced.

The most cranial soft tissue structures attached to the bone were maintained and the bone flap was reflected back. It was then covered in a sterile saline-soaked swab (Figure 2). Preserving the soft tissue structures on the flap of bone preserves the blood supply, decreasing the risk of bone death post-surgery.

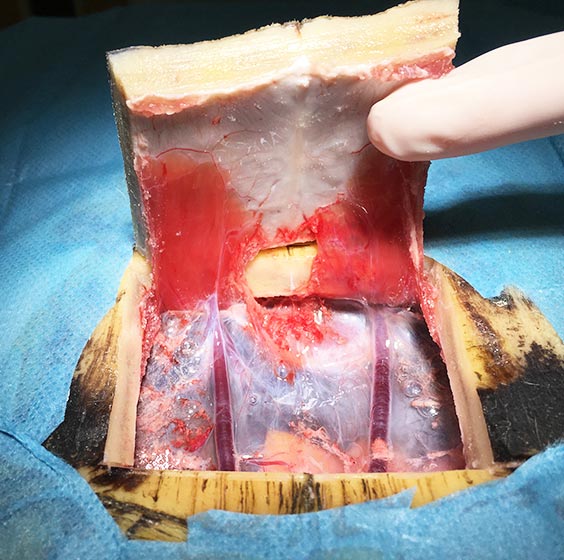

The coelomic membrane was incised at the midline in-between the two large blood vessels (Figure 3), exposing the coelomic cavity beneath.

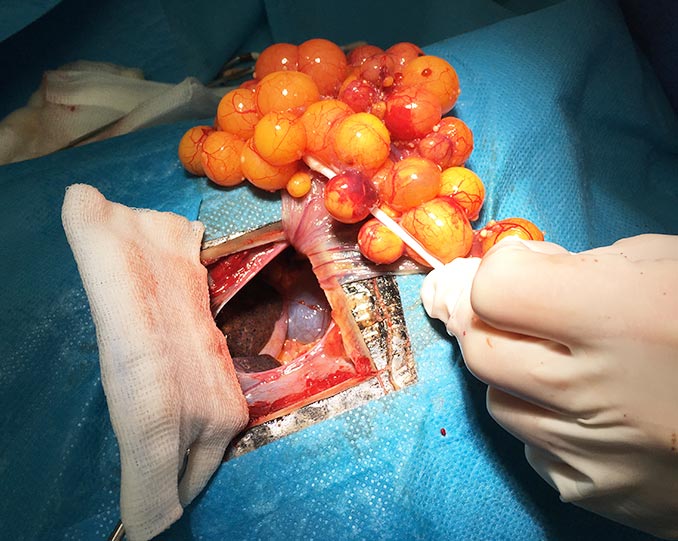

The ovaries of tortoises, with gentle lifting, are easy to exteriorise. The mesovarium is then ligated, employing a ligasure, and the ovaries and associated follicles removed from both sides (Figures 4 and 5).

In this case, to ease exteriorisation, adhesions had to be broken down between the diseased follicles and the coelomic membrane, as well as the liver. Removal of the oviductal tissue does not need to be performed, unless an obvious disease process is present. In this case, it was removed due to the level of adhesions present.

A liver biopsy for histopathology was taken prior to closure to investigate the possibility of hepatic lipidosis. The coelomic cavity was closed with simple continuous 4/0 poliglecaprone.

The space between the closed coelomic cavity and the bone flap was filled with intrasite, and the bone flap replaced and fixed in place with methyl methacrylate (Figure 6). Before the tortoise woke up, a pharangostomy tube was placed to aid in the application of medication and support feeding.

Recovery

After two days of continued analgesia using 2mg/kg morphine IM every other day and meloxicam at 0.5mg/kg via the feeding tube daily, the tortoise was sent home with continued meloxicam.

The course of ceftazidime 20mg/kg to be given every 72 hours was completed.

After three weeks of assisted feeding, using a specialised herbivore critical care food twice daily via the pharyngostomy tube – flushed before and after with 5ml of tap water (the percentage was increased over subsequent weeks, eventually reaching three per cent bodyweight) – the tortoise made a complete recovery. The pharyngostomy tube was removed once the tortoise returned to normal eating habits.