17 Jan 2023

Resistance in equine practice

Zoë Gratwick explains how and why professionals should work with owners to prevent this burgeoning one health issue.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is already a clinical problem in equine practice1. Drawing on available information, steps can be taken to minimise its rate of development. Our actions can make significant contributions to this global and local issue.

When considering antimicrobial-resistant bacteria, we may think of the direct spread of pathogens (for example, the zoonotic spread of MRSA), but the spread of resistance genes themselves is also important.

These genes can be passed into different species of bacteria, meaning bacteria once sensitive to a specific antimicrobial become resistant. This adds to the pool of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in animals, people and the environment.

Some of the most relevant antimicrobial-resistant pathogens in equine practice include MRSA, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing bacteria and multidrug-resistant bacteria. ESBLs are enzymes that inactivate extended spectrum beta-lactam antimicrobials such as ceftiofur.

The exact definition of multidrug resistance is different for different bacterial species, but it tends to mean that bacteria are resistant to at least one drug in three or more antimicrobial classes.

Why AMR in equine practice matters

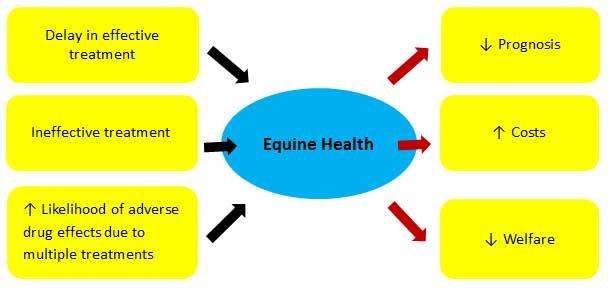

Antimicrobial-resistant infections in horses are concerning for a variety of reasons relating to equine patient health and care (Figures 1 and 2).

Antimicrobial-resistant equine infections are also important in the context of human health, because of the following reasons:

- Zoonotic transmission of contagious primary pathogens can occur.

- Zoonotic transmission of opportunistic pathogens can occur.

- Zoonotic transmission and environmental contamination with bacteria carrying genes encoding AMR can occur.

Some isolates from animals can cause immediate clinical disease in people. Alternatively, they may colonise people without causing symptoms, then act opportunistically when a subsequent surgical procedure or trauma occurs. This puts those who are colonised at increased risk of antimicrobial-resistant infections and the consequences of this.

It is recognised that MRSA infection is around four times more likely to develop in people who carry it in their nose2. This is a particular concern for vets, with multiple studies demonstrating a higher prevalence of nasal carriage in these professionals compared with non-vets.

Zoonotic transmission or contamination of the environment with bacteria carrying genes encoding AMR could lead to an increase in morbidity and mortality for affected people. Furthermore, exposure to antimicrobials leads to an increase in carriage of bacteria carrying resistance genes, which have the potential to be transferred to other bacteria.

Every time we use antimicrobials, we contribute to this situation (author’s emphasis). This is of particular importance when it comes to multidrug resistance to antimicrobials that are critically important for human health. A direct positive impact has been demonstrated between decreased antimicrobial usage in food-producing animals and decreased AMR in human pathogens3.

Three key areas for focus exist when considering practical measures against AMR in equine practice:

Conclusion

By considering these and other ways to slow the rate of development of AMR in equine practice, we can work together to limit the effect of this challenge on our patients and those who care for them.

- Use of some of the drugs mentioned in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- Reducing antimicrobial exposure can reduce the development of AMR. Decreasing the development of disease requiring antimicrobial therapy can be achieved by:

- Minimising transmission of contagious disease.

- Addressing factors predisposing to bacterial infection.

- Decreasing iatrogenic complications through good clinical hygiene.

- When considering the use of antimicrobials in prophylaxis and disease, we should ask ourselves:

- Is a bacterial infection (or high likelihood of a bacterial infection) present?

- If so, can the current infection be managed without systemic antimicrobials?

- If antimicrobials are required, do supportive treatments that could decrease the time to resolution exist?

- Optimising treatment efficacy reduces the duration of antimicrobial exposure, the number of classes to which the animal is exposed and sub-therapeutic exposure, therefore reducing the development of AMR. Antimicrobial usage can be optimised by:

- Appropriate drug selection.

- Using optimal doses and durations of therapy.

- Appropriate care of medications.

References

- Isgren CM, Williams NJ, Fletcher OD, Timofte D, Newton RJ, Maddox TW, Clegg PD and Pinchbeck GL (2022). Antimicrobial resistance in clinical bacterial isolates from horses in the UK, Equine Veterinary Journal 54(2): 390-414.

- Safdar N and Bradley EA (2008). The risk of infection after nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus, The American Journal of Medicine 121(4): 310-315.

- Tang KL, Caffrey NP, Nóbrega DB, Cork SC, Ronksley PE, Barkema HW, Polachek AJ, Ganshorn H, Sharma N, Kellner JD and Ghali WA (2017). Restricting the use of antibiotics in food-producing animals and its associations with antibiotic resistance in food-producing animals and human beings: a systematic review and meta-analysis, Lancet Planet Health 1(8): e316-e327.

- Isgren C (2021). Use of antimicrobials for routine castration. In: Antimicrobial question time, BEVA Congress 2021.

- Freeman SL, Ashton NM, Elce YA, Hammond A, Hollis AR and Quinn G (2021). BEVA primary care clinical guidelines: wound management in the horse, Equine Veterinary Journal 53(1): 18-29.

- Weese JS, Giguère S, Guardabassi L, Morley PS, Papich M, Ricciuto DR and Sykes JE (2015). ACVIM consensus statement on therapeutic antimicrobial use in animals and antimicrobial resistance, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 29(2): 487-498.

- Hardefeldt LY, Bailey KE and Slater J (2021). Overview of the use of antimicrobial drugs for the treatment of bacterial infections in horses, Equine Veterinary Education 33(11): 602-611.

- Gullberg E, Cao S, Berg OG, Ilbäck C, Sandegren L, Hughes D and Andersson DI (2011). Selection of resistant bacteria at very low antibiotic concentrations, Plos Pathogens 7(7): e1002158.

- Hanretty AM and Gallagher JC (2018). Shortened courses of antibiotics for bacterial infections: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials, Pharmacotherapy 38(6): 674-687.

- Clare S, Hartmann FA, Jooss M, Bachar E, Wong YY, Trepanier LA and Viviano KR (2014). Short- and long-term cure rates of short-duration trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole treatment in female dogs with uncomplicated bacterial cystitis, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 28(3): 818-826.