25 Nov 2025

Reviewing clinical approach to managing acute pain in horses

Jake Leech BVetMed, MRCVS and Thaleia Stathopoulou DVM, MVetMed, DipECVAA, MRCVS consider the analgesic and anaesthetic options best suited to use in equids.

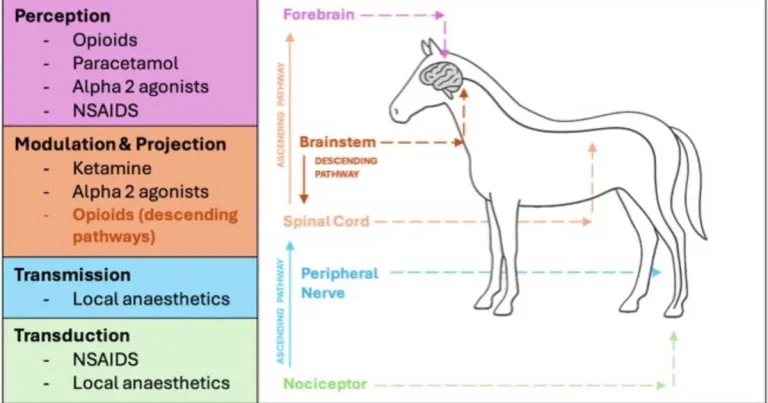

Figure 1. The pain pathway and location of action of the analgesic drug classes commonly used in the management of acute pain in horses.

Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience resulting from actual or potential tissue damage (Raja et al, 2020). Acute pain in horses has historically been more challenging to manage compared to in dogs and cats because of licensing, a relative lack of research, and species-specific side effects of some analgesics.

The horse’s innate ability as a prey species to hide pain is important to recognise and it can make acute pain both highly difficult to assess and evasive pain behaviours hard to predict (Taylor et al, 2002). The rationale for the appropriate management of acute pain, therefore, extends beyond ethics and patient care, but also as a means of mitigating risk for those interacting with painful horses.

Although primarily discussed in the context of perioperative analgesia, the principles outlined in this review can be applied to other acute pain aetiologies secondary to a whole host of traumas and medical conditions. Maladaptive pain conditions can develop from improperly managed acute pain.

Chronic pain, albeit a relevant welfare concern in horses, often associated with conditions such as osteoarthritis and laminitis, is beyond the scope of this article.

Acute pain physiology

A cascade of physiological processes is initiated by tissue injury resulting mainly in withdrawal, haemostasis and inflammation to reduce further interaction with a damaging stimulus.

Pain propagation and perception follow a neurotypical pathway from receptor to the central nervous system. The pain pathway has four steps, broadly associated with four anatomical components of the nervous system: nociceptors, peripheral nerves, the spinal cord and the brain, at which transduction, transmission, modulation and perception occur, respectively (Figure 1).

Transduction is the initiation of an action potential at the nociceptor in response to the overcoming of a threshold potential by chemical, mechanical and thermal stimuli. Following transduction, information is conducted proximally along nerves in a process known as transmission, before synapsing in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord where pain modulation occurs. Here, pain signals are amplified or inhibited before reaching the pain centres in the cerebral cortex, where the actual emotional and conscious experience of pain takes place.

Interestingly, pain does not only travel from the periphery to the brain (ascending pathways). Descending pathways from the brain and brainstem to the spinal cord and periphery can either inhibit or increase the sensation of pain using neurotransmitters (such as serotonin or norepinephrine). This constitutes an element of internal pain control that can be manipulated by different analgesics.

The term nociception describes the physiological transmission of “pain” under general anaesthesia and includes the steps of transduction, transmission and modulation without central perception. Despite the lack of conscious awareness, a sympatho-adrenal stress response, tissue damage and the possible chronic effects of which still occur, highlighting the importance of treating pain at the different points along the pain pathway under anaesthesia (Pirie et al, 2022).

Acute pain assessment

Consistent and reliable pain assessment is important for pain recognition and monitoring of the effectiveness of analgesia. It can be challenging in horses, mainly due to their stoic nature and the poor correlation between physiological parameters such as heart rate, respiratory rate and pain intensity (Raekallio et al, 1997).

Several pain scores are described in horses, specific to different acute pain pathologies. The most commonly used scores are the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS), the Composite Pain Scale (CPS) and the Equine Acute Abdominal Pain Scale (EAAPS). A review of the approach and application of systematic pain assessment in horses by De Grauw and van Loon (2016) provides a more detailed summary on the topic.

The HGS is validated for assessment of postoperative pain following castration in gelded horses (Dalla Costa et al, 2014). Horses are scored 0, 1 or 2 based on the absence, mild presence or obvious presence of six facial changes. Areas of focus include the eyes, ears, nostrils, chin, mouth and masticatory muscles, the position, shape and tone of which changes in response to pain.

The CPS uses several indices of pain and has been validated in adult horses for the assessment of somatic and some orthopaedic pain conditions, incorporating physiological and behavioural parameters (Bussières et al, 2008). Further refined and modified versions of the equine CPS have since been developed (Van Loon et al, 2010; Van Loon and Van Dierendonck, 2015). The EAAPS, meanwhile, is a simple descriptive scale that has been validated for assessment of visceral pain associated with colic (Sutton et al, 2013).

Assessment involves observing behaviours associated with increasing levels of visceral pain from flank watching (score 1) to rolling (score 5).

Treatment of acute pain

Treatment of acute pain is based upon the principles of pre-emptive and multimodal analgesia. Pre-emptive analgesia is the provision of analgesic drugs before noxious stimulation occurs, reducing the intraoperative and postoperative requirements for analgesia.

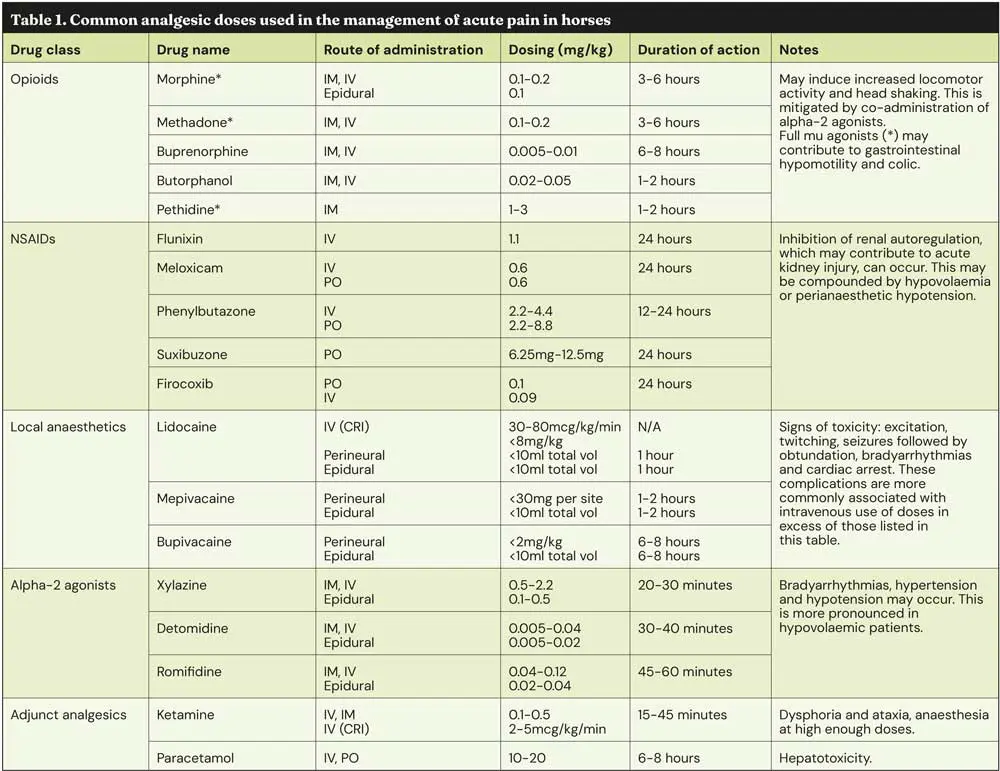

Multimodal analgesia refers to the use of two or more analgesic agents with different mechanisms and sites of action along the pain pathway (Figure 1). This enables clinically relevant reductions in doses and, therefore, side effects of the individual agents. Table 1 is a summary of some of the most commonly used acute analgesic agents in horses.

Opioids

Opioids have been a mainstay of acute analgesia in human and veterinary medicine for hundreds of years (Clutton, 2010).

Opioids produce their effects and side effects by binding to opioid receptors (mu, delta and kappa) in the brain, the spinal cord and other organs. They initiate a cascade that results in the reduction and upregulation of the pain signalling in ascending and descending pathways, respectively (Pathan and Williams, 2012).

Opioids acting on mu-receptors, such as morphine, produce profound analgesia, while opioids acting on kappa receptors, such as butorphanol, result in less intense analgesia, but they are also linked with fewer side effects.

Excitation and increased locomotor activity following opioid administration are documented in horses. Experimental studies have demonstrated this to be more pronounced in non-painful horses, and so appropriate use of full mu agonists as part of balanced surgical analgesia is advisable (Sanchez and Robertson, 2014).

Concerns surrounding decreased gastrointestinal motility are legitimate, but the role of pain and stress in the development of these same issues must also be considered. The negative effects of increased sympathetic tone on gastrointestinal motility, secretion and perfusion are also well described (Cervi et al, 2014).

NSAIDs

NSAIDs form the backbone of acute analgesic management of horses. They inhibit cyclooxygenase enzymes to reduce the production of prostaglandins, which are key mediators of inflammation and pain.

Tissue inflammation is common to almost all acute pain aetiologies, including perioperative pain. NSAIDs should, therefore, be utilised unless a good reason exists not to. Deleterious side effects such as dysregulation of renal autoregulation (Van Galen et al, 2024), impairment of mucosal integrity and development of right dorsal colitis (Davis, 2015) need to be balanced against the benefits of anti-inflammation and analgesia.

Alpha-2 agonists

Although primarily used as reliable sedative agents, alpha-2 agonists such as xylazine, detomidine and romifidine also have profound antinociceptive properties. They act centrally as sympatholytic drugs to reduce pain perception, as well as modulating ascending pain signals in the spinal cord.

Alpha-2 agonists play a fundamental role in providing multimodal analgesia for acute abdominal pain associated with colic, as well as perioperatively. Infusions of alpha-2 agonists can help maintain suitable analgesic conditions, as well as immobilisation to perform many procedures in standing sedated horses.

Adjunctive analgesics: systemic ketamine and lidocaine

Ketamine is mainly a NMDA antagonist. However, it also interacts with the opioid and muscarinic receptors, and has some mild local anaesthetic-like properties. It is the most common injectable anaesthetic in horses, and it can also be used at subanaesthetic doses for its analgesic properties.

Ketamine use is also significant for chronic pain, since it inhibits central sensitisation and can be considered an anti-hyperalgesic (Lin et al, 2014).

Lidocaine is an amine local anaesthetic that is most commonly proposed as a visceral analgesic. Systemically, its mechanism of action has not been fully elucidated, but is likely to include action at sodium, calcium, potassium and NMDA receptors (Doherty and Seddighi, 2010).

Evidence around the use of systemic lidocaine in horses is mixed. Several publications have demonstrated the volatile anaesthetic-sparing effects of intravenous lidocaine (Rezende et al, 2011; Dzikiti et al, 2003). However, evidence for the analgesic effect of lidocaine is conflicting.

It is worth mentioning that lidocaine infusion improved outcomes and decreased postoperative reflux in horses undergoing celiotomy for small intestinal disease (Durket et al, 2019).

More evidence is needed to fully elucidate the benefits and limitations of intravenous lidocaine in equine analgesia and perioperative care.

Local anaesthetics: locoregional techniques

Locoregional techniques using local anaesthetic agents are the most effective means of acute pain management and are widely used to facilitate standing sedated surgical procedures in horses, sparing the inherent risks of general anaesthesia.

Local anaesthetics such as mepivacaine, lidocaine and bupivacaine work by reversibly blocking the voltage-gated sodium channels on nerve membranes, and prevent pain signal transmission (Taylor and McLeod, 2020).

The benefits of locoregional anaesthesia are numerous: systemic analgesic dose reductions, reduced reliance on sedative agents and mitigation of the adrenocortical response to surgical stimulation, to name a few.

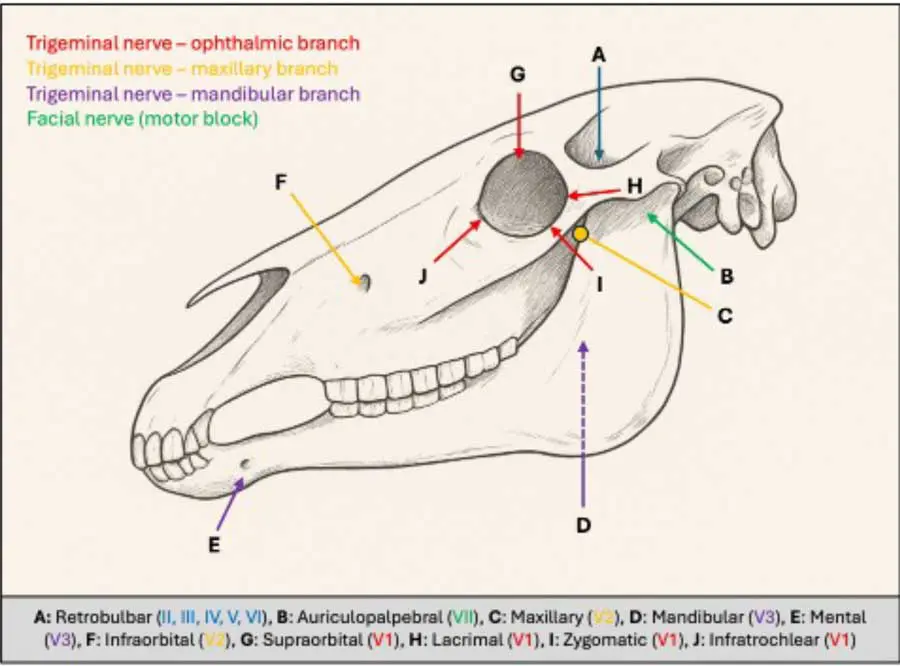

Several local anaesthetic techniques can be employed during the surgical management of conditions in the standing sedated horse. Figure 2 outlines the injection points and relevant target nerves to provide analgesia for procedures such as dental extractions, ophthalmic examination and enucleation. Branches of the trigeminal nerve are the primary target for analgesia of the head and face, most of which can be easily performed under sedation using landmarks on the head. The use of anatomical landmarks means that patient and operator variability can result in block failure, and so the concurrent use of systemic analgesics is advisable.

Locoregional blocks of the distal limb are most frequently used for diagnostic lameness assessment, but can also be employed therapeutically in sedated and anaesthetised horses.

Barker (2016) provides an excellent summary of the indications, pharmacology and techniques.

Many ultrasound-guided locoregional blocks such as the erector spinous plane block (Freitag et al, 2021), the transverse abdominis plane block (Delgado et al, 2021) and the cervical plexus block (Campoy et al, 2018) have been described in horses. These are applicable to the analgesic management of horses under both general anaesthesia and standing sedation. This is an area of equine analgesia that is likely to develop greatly over the next few years.

Epidural analgesia

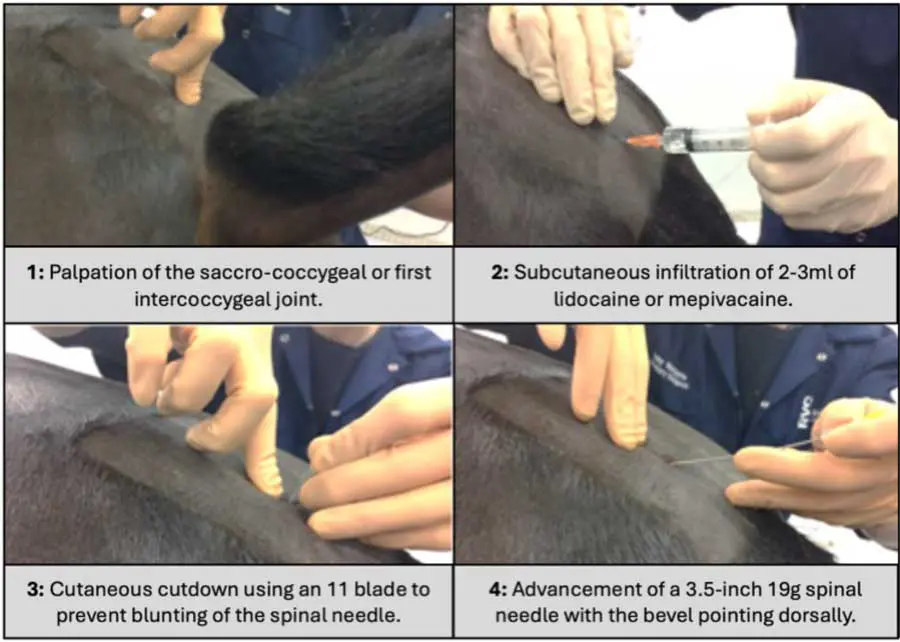

Epidural analgesia can be used to facilitate perineal, genital and hindlimb procedures, either in the standing sedated or anaesthetised horse.

The technique involves the administration of drugs into the epidural space (Figure 3). In doing so, analgesics are concentrated at the site where modulation and propagation to the brain occurs, while also minimising systemic side effects. If available, then preservative-free formulations of drugs should be used, owing to concerns surrounding the potentially neurotoxic effects of some preservatives (Munir et al, 2000).

Morphine is commonly used in equine epidural administration as it is relatively less lipophilic compared to many other analgesics. This slows its systemic absorption from the fat-rich epidural space, extending the duration and analgesic benefit (Morgan, 1989).

Alpha-2 agonists in the epidural space interact directly with the nearby dorsal horn and provide analgesia, as well as reducing the systemic absorption of co-administered drugs through local vasoconstriction (Natalini et al, 2021). It should be noted that no preservative-free formulations of alpha-2 agonists are commercially available.

Local anaesthetics should be used cautiously in the epidural space – particularly in standing sedated horses – with attention to the volume of drugs administered. Infusion of large or frequent volumes of local anaesthetics risks greater spread of the fluid cranially that could affect the femoral and sciatic nerve, and result in possible collapse of the horse (Bird et al, 2018).

Low volumes of local anaesthetic can still be used to provide sensory blockade to the perineum and genitalia, for example, to facilitate anal melanoma resection in standing horses (Robert et al, 2024).

Repeated or continuous epidural administration can be facilitated through placement of an epidural catheter.

Conclusion

The role of successful anaesthesia and analgesia is of paramount importance for patient welfare and the safety of the veterinary team.

Appropriate detection and management of acute pain should, therefore, remain a priority for ongoing research in the field of equine medicine and surgery.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 47, Pages 6-10

Jake Leech BVetMed, MRCVS is a final-year resident of the European College of Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia, and works at the RVC.

Thaleia Stathopoulou DVM, MVetMed, DipECVAA, MRCVS is a European specialist in veterinary anaesthesia and analgesia, and works at the RVC. She is particularly interested in local anaesthesia, perioperative analgesia and the uses of opioids. Thaleia has also been involved in translational research regarding neuromodulation and heart transplants.

References

- Barker W (2016). Equine distal limb diagnostic anaesthesia: (1) Basic principles and perineural techniques, In Practice 38(2): 82-90.

- Bird AR, Morley SJ, Sherlock CE and Mair TS (2018). The outcomes of epidural anaesthesia in horses with perineal and tail melanomas: complications associated with ataxia and the risks of rope recovery, Equine Veterinary Education 31(11): 567-574.

- Bussières G, Jacques C, Lainay O et al (2008). Development of a composite orthopaedic pain scale in horses, Research in Veterinary Science 85(2): 294-306.

- Campoy L, Morris TB, Ducharme NG et al (2018). Unilateral cervical plexus block for prosthetic laryngoplasty in the standing horse, Equine Veterinary Journal 50(6): 727-732.

- Cervi AL, Lukewich MK and Lomax AE (2014). Neural regulation of gastrointestinal inflammation: role of the sympathetic nervous system, Autonomic Neuroscience 182: 83-88.

- Clutton RE (2010). Opioid analgesia in horses, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice 26(3): 493-514.

- Dalla Costa E, Minero M, Lebelt D et al (2014). Development of the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) as a pain assessment tool in horses undergoing routine castration, Plos One 9(3): e92281.

- Davis JL (2015). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated right dorsal colitis in the horse, Equine Veterinary Education 29(2): 104-113.

- De Grauw JC and van Loon JPAM (2016). Systematic pain assessment in horses, The Veterinary Journal 209: 14-22.

- Delgado OBD, Louro LF, Rocchigiani G et al (2021). Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block in horses: a cadaver study, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 48(4): 577-584.

- Doherty TJ and Seddighi MR (2010). Local anesthetics as pain therapy in horses, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice 26(3): 533-549.

- Durket E, Gillen A, Kottwitz J and Munsterman A (2019). Meta-analysis of the effects of lidocaine on postoperative reflux in the horse, Veterinary Surgery 49(1): 44-52.

- Dzikiti TB, Hellebrekers LJ and Dijk P (2003). Effects of intravenous lidocaine on isoflurane concentration, physiological parameters, metabolic parameters and stress-related hormones in horses undergoing surgery, Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series A 50(4): 190-195.

- Freitag FAV, Amora Jr DDS, Muehlbauer E et al (2021). Ultrasound-guided modified subcostal transversus abdominis plane block and influence of recumbency position on dye spread in equine cadavers, Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 48(4): 596-602.

- Lin HC, Passler T, Wilborn RR et al (2014). A review of the general pharmacology of ketamine and its clinical use for injectable anaesthesia in horses, Equine Veterinary Education 27(3): 146-155.

- Morgan M (1989). The rational use of intrathecal and extradural opioids, British Journal of Anaesthesia 63(2): 165-188.

- Munir MA, Krishnan S and Ahmad M (2000). A simple technique to reduce preservative/excipient related neurotoxicity of intrathecal (spinal) drugs, Anesthesia and Analgesia 90(3): 767-768.

- Natalini CC, Paes SD and Polydoro ADS (2021). Analgesic and cardiopulmonary effects of epidural romifidine and morphine combination in horses, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 102: 103459.

- Pathan H and Williams J (2012). Basic opioid pharmacology: an update, British Journal of Pain 6(1): 11-16.

- Pirie K, Traer E, Finniss D et al (2022). Current approaches to acute postoperative pain management after major abdominal surgery: a narrative review and future directions, British Journal of Anaesthesia 129(3): 378-393.

- Raekallio M, Taylor PM and Bennett RC (1997). Preliminary investigations of pain and analgesia assessment in horses administered phenylbutazone or placebo after arthroscopic surgery, Veterinary Surgery 26(2): 150-155.

- Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M et al (2020). The Revised International Association for the Study of Pain Definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises, Pain 161(9): 1,976-1,982.

- Rezende ML, Wagner AE, Mama KR et al (2011). Effects of intravenous administration of lidocaine on the minimum alveolar concentration of sevoflurane in horses, American Journal of Veterinary Research 72(4): 446-451.

- Robert MP, Buyck C, Tricaud C et al (2024). Radical surgical excision of extensive perianal melanomas on standing horses: Twenty cases, Veterinary Surgery 54(2): 373-381.

- Sanchez LC and Robertson SA (2014). Pain control in horses: What do we really know?, Equine Veterinary Journal 46(4): 517-523.

- Sutton GA, Paltiel O, Soffer M and Turner D (2013). Validation of two behaviour-based pain scales for horses with acute colic, The Veterinary Journal 197(3): 646-650.

- Taylor A and McLeod G (2020). Basic pharmacology of local anaesthetics, BJA Education 20(2): 34-41.

- Taylor PM, Pascoe PJ and Mama KR (2002). Diagnosing and treating pain in the horse, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Equine Practice 18(1): 1-19.

- Van Galen G, Divers TJ, Savage V et al (2024). ECEIM consensus statement on equine kidney disease, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 38(4): 2,008-2,025.

- Van Loon JPAM, Back W, Hellebrekers LJ and van Weeren PR (2010). Application of a Composite Pain Scale to objectively monitor horses with somatic and visceral pain under hospital conditions, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 30(11): 641-649.

- Van Loon JPAM and Van Dierendonck MC (2015). Monitoring acute equine visceral pain with the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Composite Pain Assessment (EQUUS-COMPASS) and the Equine Utrecht University Scale for Facial Assessment of Pain (EQUUS-FAP): A scale-construction study, The Veterinary Journal 206(3): 356-364.