12 Jan 2021

Ann Derham provides a brief overview of such injuries, including the mainstay of management and the exciting field of regenerative medicine.

Strain-induced tendon injuries are not a new occurrence. They are, unfortunately, common in our athletic horses, and are particularly prevalent in racehorses, where their tendons are working at their upper limit.

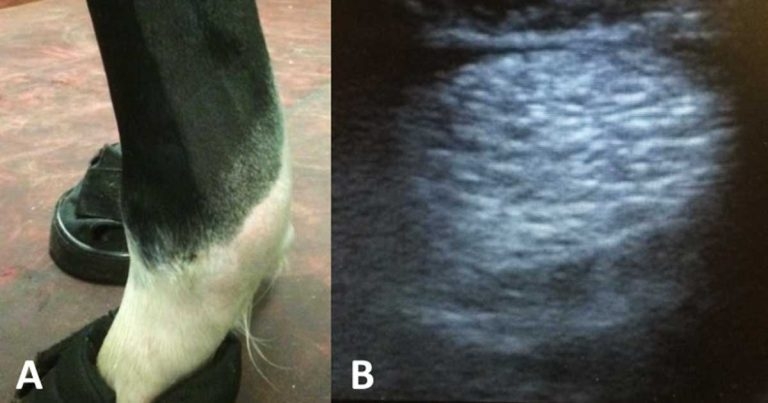

As with any injury, a thorough clinical exam is a crucial part of the assessment. A history of lameness after a period of exercise is a typical complaint. For subtle changes, comparing the affected limb to the contralateral limb provides valuable information (Figure 1).

Some injuries can lead to specific postural abnormalities, for example:

The affected limb should then be carefully and thoroughly palpated – again comparing this to the normal limb. Some horses get irritated quite quickly – especially when in pain, so examining the normal leg first is usually advised. During palpation of the limb, careful attention should be paid to the presence of any heat, painful response to light or hard pressure, subtle enlargements and consistency of the tissue (soft after recent injury; firm if chronic).

Always check for evidence of trauma, such as a small wound, during the exam.

Lameness is often severe in the acute stages and will subside within one to two weeks once the inflammation phase has subsided. Lameness severity, progression and resolution will, however, depend on the structure(s) involved, location of the injury and disease stage.

Ultrasound is an invaluable part of the exam as it will provide you with an assessment of severity, which, in turn, can help guide treatment, management and prognosis.

The optimal time for a baseline scan is approximately seven days after the initial injury. Scanning earlier than this can lead to an “underestimation” of lesion severity.

While reasonable images can be achieved without clipping in fine-breed horses, for an accurate assessment, clipping and preparation of the region, followed by an alcohol soak, will offer the best chance for gaining diagnostic images. This is even more relevant for the inexperienced scanner.

Comparing the affected limb with the contralateral leg should be done, not only for comparison, but also because palmar lesions can be bilateral in one out of three cases.

A linear transducer with a frequency of 7.5MHz is best. If this is unavailable, a rectal probe will work well for superficial structures, such as suspensory branches, and flexor and extensor tendons.

Have the horse standing square if possible; images should be taken in both the transverse and longitudinal plane, along with oblique images and non-weight-bearing images.

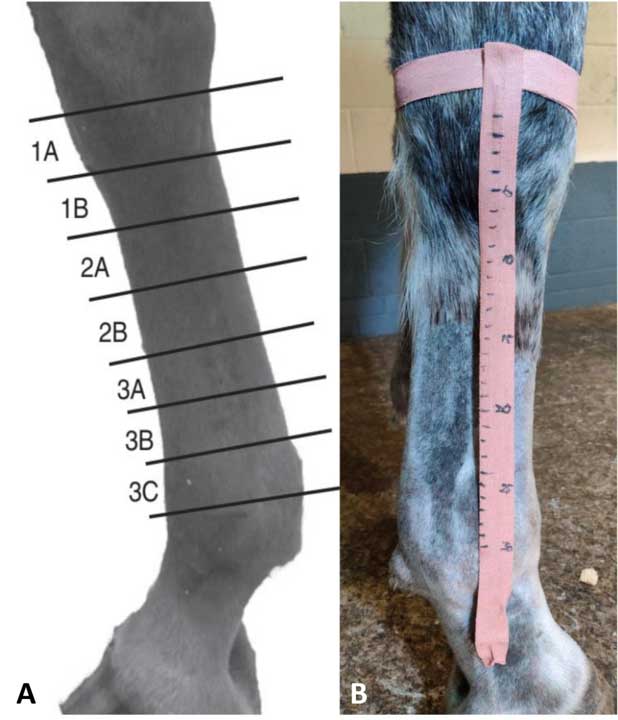

Two methods are used for identifying the location of lesions in the distal limb:

Acute tendon pathology is characterised by changes in shape, margins and enlargement, focal or generalised hypoechogenicity, and reduced fibre pattern. In cases of chronic tendinopathy with fibrosis, one may see variable enlargement, echogenicity and irregular fibre pattern.

In some cases, ultrasound may not give you a definitive diagnosis – for example, longitudinal tears in the DDFT – and further imaging is required. Contrast radiography of the digital flexor tendon sheath (Figure 3) is commonly performed to identify lesions causing tenosynovitis, such as manica flexoria tears. Advanced imaging, such as with CT and MRI, is also extremely useful in diagnosing lesions involving the distal DDFT and other soft tissue structures of the foot that can be difficult or impossible to diagnose on ultrasound.

Some markers of collagen synthesis have been shown to increase in tendinopathy; however, their clinical use in equine orthopaedic medicine is currently in the early stages.

The hope is they may provide useful parameters to evaluate tendon disease and be able to provide a diagnosis when other tests are negative or be used as a screening measure in horses at risk of tendinopathies.

A lot of treatments have been proposed, but few, if any, have much convincing evidence behind them. The basic principles of cooling, support and rest remain a mainstay of the treatment and management of tendon injuries.

Acute tendon injuries should be considered medical emergencies, with prompt treatment needed to reduce inflammation and minimise further tendon damage.

During the acute phase, phenylbutazone (2.2mg/kg by mouth/IV twice a day) should be given. If within the first 24 to 48 hours of injury corticosteroids can be given (dexamethasone 0.1mg/kg IV single dose), their use should be avoided after the initial 48 hours as they inhibit fibroplasia and tendon repair.

Cold therapy is indicated during acute inflammation, as it provides both anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects. It is recommended cold therapy be done for no longer than periods of 20 to 30 minutes, as prolonged exposure may cause reflex vasodilatation, which can worsen swelling and oedema.

Cold therapy has been shown to be superior to ice packs because of increased contact and evaporation, and less adverse effects (such as superficial tissue damage or nerve palsy). Equine spas are a very effective way of providing both cold and compression.

During the acute phase of injury, pressure should be applied to the region to reduce inflammation and oedema by increasing interstitial hydrostatic pressure. In most cases, a modified Robert Jones bandage is suitable. In cases with fetlock hyperextension, a palmar/plantar splint or a cast should be applied. Specially designed support boots are commercially available.

Some debate exists over the most appropriate type of shoeing. For short-term management of DDFT tendinopathy, raising the heels can help reduce tension on the tendon. Long-term use of raised heels should be avoided, as it will lead to heel collapse. This practice should also be avoided when damage to the primary supporting structures of the fetlock (suspensory ligament, SDFT) exists, as this increases the loads on these structures.

Historically, in cases of SDFT or suspensory ligament involvement, extended length or increased width at the heels or an egg-bar shoe have been used. More recently, raising the toe or placing a shoe with a wider toe width to help reduce the forces on these structures has been suggested.

This is an integral part of the management of tendon lesions. Most SDFT and DDFT injuries can take up to 12 months of rehabilitation before going back into full athletic function. Exercise programmes are tailored to the animal and lesion severity. The aim of introducing a controlled, gradually increasing programme is to optimise scar tissue function, maintain the gliding function of the tendon and promote optimal collagen remodelling, without causing further injury. Table 1 provides an example of such a programme (Kummerle et al, 2018).

Developing an appropriate programme can be hard and should be adapted based on serial ultrasound exams to ensure the tendon can withstand the exercise. This can be done at set time points – for instance, every two to three months – or before and after upward transitions have been introduced to the programme; namely, from walk to trot, trot to canter and canter to gallop. An increase in the cross-sectional area of the tendon by more than 10 per cent between exams is highly suggestive of re-injury, and the exercise level should be reduced.

Underwater treadmills, in conjunction with a controlled exercise programme, should be considered as they allow for musculoskeletal conditioning with minimal concussive forces.

| Table 1. An example of an exercise programme for the first 16 weeks | ||

|---|---|---|

| Exercise level | Weeks | Duration and exercise type |

| 0 | 0-2 | Box rest |

| 1 | 3 | 10 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 4 | 15 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 5 | 20 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 6 | 25 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 7 | 30 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 8 | 35 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 9 | 40 minutes hand walking |

| 1 | 10-12 | 45 minutes hand walking |

| Week 12: repeat ultrasound | ||

| 2 | 13-16 | 40 minutes walking plus 5 minutes trotting |

The mechanism of action for extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is still unclear, but it likely causes analgesia through its effect on the sensory nerves. ESWT is probably most commonly used for the treatment of proximal suspensory desmitis.

Currently, few controlled objective equine studies demonstrate the use of therapeutic ultrasound and magnetic fields in tendon healing. Class IV (surgical) lasers have shown some anecdotal success in improving tendon repair quality, but further research into their use in equine clinical cases are warranted.

Counter-irritation has been long used, either applied chemically (topical iodine compounds) or thermally (firing or freezing) to the skin over the injured site. The limited controlled studies done on firing have concluded it is not an effective treatment for tendon injuries; any improvement seen is likely as a result of the forced box rest and anti-inflammatories.

This should be done no earlier than three days after initial injury, and only after full aseptic preparation of the limb. Ultrasound-guided injection of the standing sedated horse following local anaesthesia of the limb is the most common technique. Ultrasound-guided injection optimises correct placement and allows injection of the optimal volume of treatment via a 22g hypodermic needle (larger gauge should be used if cells are being injected).

Regenerative medicine techniques, including platelet-rich plasma and autologous conditioned serum, have shown promising results, with quicker reductions in lameness seen, and they are commonly used in equine practice.

Polysulphated glycoaminoglycans and hyaluronic acid (HA) have also been used, but evidence is conflicting on their efficacy when re-injury rates are studied.

HA is probably best used intrathecally to try to reduce the risk of adhesions forming within the tendon sheath. Methylprednisolone should be avoided as it causes dystrophic tissue mineralisation and tissue necrosis. Acellular matrix of porcine urinary bladder submucosa was marketed as an additional therapy; however, clinical studies have been disappointing and concerns over xenogenic implant reactions have kept it from becoming widely used.

Cell-based therapies to regenerate diseased tendon, such as mesenchymal stem cells, have shown high potential and their use is becoming more common in equine practice. However, these still remain cost-prohibitive to many clients.

Currently, research into alternative routes of administration to intralesional injections are being researched, such as IV regional perfusion. This would be extremely beneficial for lesions that cannot be directly accessed or where needle-induced iatrogenic damage to surrounding tissue is of concern.

A vast amount of techniques are available, depending on the structure(s) involved and chronicity of the lesion.

Tendon splitting may be indicated for an acute tendinopathy to remove a seroma/haematoma from the lesion “decompress”, which may help prevent lesion propagation. This technique should be avoided in chronic cases as it leads to extensive granulation tissue, increased tendon trauma and persistent lameness.

Tenoscopy/bursoscopy is advantageous as it provides both assessment of the lesion and surgical management in one sitting. The digital flexor tendon sheath is the most commonly scoped tendon sheath in the horse and is performed for a variety of conditions (manica flexoria tears, palmar/plantar annular ligament constriction, longitudinal tears of the DDFT, tenosynovitis and sepsis).

Tendon injuries are commonly diagnosed in our equine patients. The mainstay of managing the acute injury is cold therapy, anti-inflammatories, compression, support and rest.

Ultrasound remains crucial to the diagnosis of most tendon lesions, and guides the practitioner on severity and treatment options. Regenerative medicine is becoming increasingly popular and has shown promising results. Surgical management may be warranted depending on the type of injury, severity, the athletic aims of the horse or if medical management fails.