14 Jul 2021

Karin Kruger discusses equine gastric ulcer syndrome, which is currently differentiated into two distinct disease syndromes that require their own strategies from equine vets.

Equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) is extremely common, with incidence reaching 80% to 100% in performance horses. Within EGUS, we currently differentiate two distinct disease syndromes requiring different treatment and control strategies, namely equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD) and equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD).

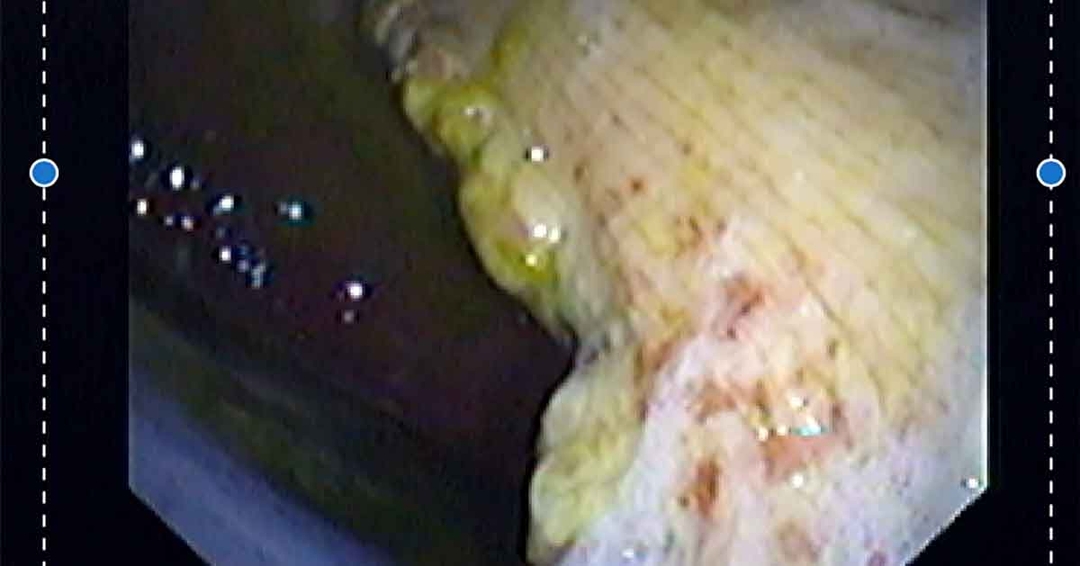

A variety of clinical signs have been associated with EGUS, including poor appetite/picky eating, weight loss, chronic diarrhoea, poor coat condition, bruxism, behavioural changes, colic and poor performance. Gastroscopy remains the only reliable method to identify gastric ulcers. Based on gastroscopy findings, ESGD lesions are assigned a score from 0-4, based on a grading system adapted from the 1999 EGUS council (Table 1)1. No universally accepted grading system is available for EGGD.

| Table 1. Grading system for equine squamous gastric disease1 | |

|---|---|

| Grade | Squamous mucosa |

| 0 | Intact epithelium and no evidence of hyperkeratosis |

| 1 | Intact mucosa with areas of hyperkeratosis |

| 2 | Small, single or multifocal lesions |

| 3 | Large, single or extensive superficial lesions |

| 4 | Extensive lesions with areas of apparent deep ulceration |

For her clinical notes, the author finds it most useful to describe the lesions, in addition to saving images for future reference. This is to document how lesions progressed at re-check, but also because deeper lesions (even smaller ones) heal much slower than more superficial lesions, which influences the decision on duration of treatment.

Important descriptive information includes the number, size, location, depth and appearance (raised/flat/haemorrhagic/depressed/fibrinosuppurative) of each lesion and the presence or absence of hyperkeratosis, which is associated with chronicity. While it can be useful to categorise lesions numerically for research purposes, this author doesn’t find the grading system particularly helpful from a clinical perspective, possibly due to the large variation in clinical response to treatment.

Some horses with mild lesions show a massive response to treatment, while others with much more severe lesions appear to have no detectable response to lesion resolution. To put it a different way, a horse with grade 1 lesions or only mild focal superficial glandular erosions with a primary complaint of bucking its rider off can have complete resolution of abnormal behaviour with resolution of its “mild” EGUS, while a horse with the same behavioural issues and much more severe lesions can have no notable response to treatment and lesion resolution.

Due to the widespread availability of gastroscopy equipment, gastric lesions are easily visualised. One of the practitioner’s biggest challenges is to determine whether a horse’s ulcers are contributing to its primary complaint, which is easier said than done. It is important to consider other potential causes of the primary client complaint and to beware of ideolepsis.

Risk factors for ESGD and EGGD are not the same, reinforcing the fact that squamous and glandular disease are two entirely separate disease entities. Increased management and exercise intensity, as well as high-grain diets, increase the risk of ESGD, but the same is not true for EGGD. Only 25% of Thoroughbred racehorses in Australia had EGGD. This is much lower than the 54% of leisure horses and 64% sport horses with EGGD in a UK study, or the 72% of Canadian warmblood showjumpers and 57% of Danish horses reported to have EGGD.

Warmblood breed, and exercise frequency greater than five times per week, regardless of exercise intensity, are risk factors for EGGD. In contrast to ESGD, dietary factors do not appear to affect EGGD risk, but stress and individual trainers do2-5.

ESGD occurs predominantly due to increased exposure of the squamous mucosa to hydrochloric acid. It follows that treatment should focus on decreasing gastric acid and managing acid splash with a good fibrous mat in the stomach. The proton pump inhibitor omeprazole remains the treatment of choice for ESGD. Omeprazole inhibits acid secretion by irreversibly binding to the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. To secrete acid, new pumps have to be generated. Since omeprazole itself is acid-labile, it is presented in either buffered paste or enteric-coated formulations. Reported ESGD healing rates for the buffered paste at 4mg/kg for 28 days are 70% to 77%.

The omeprazole powder paste bioavailability is, unfortunately, significantly impacted by feed and individual variation. Independent of feed factors, some horses simply don’t absorb it as well as others. This may be one reason why we see treatment failures. While originally licensed at 4mg/kg for 28 days, the buffered paste formulations of omeprazole can be effective at much lower dosages in certain individuals.

Bioavailability is also significantly increased when given in a “fasted” state. This fasted state can be achieved by giving horses only enough night-time hay to last until midnight, and then administering the paste prior to the morning feed. I typically advise owners to administer the paste 30 to 60 minutes prior to the first morning feed. In this way, 2mg/kg can be as effective as 4mg/kg in fed horses, which is useful when cost is a treatment-limiting factor. Many horses will also heal their squamous ulcers well before the four-week mark, and those that are going to heal by four weeks are typically already healed within three weeks. It may, therefore, be prudent to perform follow-up gastroscopy at three weeks to determine the need for ongoing acid suppression.

In addition to the buffered paste formulations, we now also have enteric-coated granules licensed in the UK. The bioavailability of the enteric-coated formulation is not significantly impacted by feed. Although less well studied, mucosal healing also appears to occur at lower mg/kg dosages of this formulation, which is also much more affordable (Table 2). In one study, mucosal healing rates did not differ between groups treated with an enteric-coated granule at 1mg/kg, compared to the buffered paste at 4mg/kg.

| Table 2. Available licensed omeprazole formulation costs at online pharmacies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently available licensed products in the UK | Manufacturer | Cost online (Viovet/Animed) | Omeprazole formulation |

| Equizol 400mg Gastro-resistant granules for horses | CP Pharma Handelsgesellschaft | £201.49 per 28 sachets = 7.20/day | Enteric-coated granule |

| GastroGard 370mg/g oral paste | Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health | £249.95 per 14 syringes = £17.85/day | Buffered paste |

| Peptizole 370mg/g oral paste for horses | Norbrook Laboratories | £136.99 per 7 syringes = £19.57/day | Buffered paste |

| Ulcergold 370mg/g oral paste for horses | Norbrook Laboratories | £138.92 per 7 syringes = £19.84/day | Buffered paste |

The author has a clinical impression that specific horses respond better to either the buffered powder paste or the enteric-coated formulation, as switching drugs (both ways) in non-responders has, on occasion, resulted in significant improvement in clinical signs. She has, unfortunately, not been able to confirm her clinical suspicions with gastroscopy in all cases, and this impression needs to be subject to further study1,6-8.

A lot less is known about the pathogenesis and treatment of EGGD. Plausible theories for contributing factors include dysbiosis of the mucosal microbiome, mucosal inflammation, psychological and/or physiological stress, and anti-prostaglandin treatments that all lead to breakdown of the body’s normal mucosal protective mechanisms6,9.

Although acid is not primarily responsible for the development of EGGD, its presence in the stomach is believed to inhibit healing of glandular lesions. For this reason, omeprazole has traditionally been included in the treatment of glandular ulcers, although glandular ulcers don’t respond well to omeprazole monotherapy.

With 28 to 35 days of 4mg/kg buffered omeprazole paste, a healing rate of only 25% is reported. Combining omeprazole with either misoprostol at 5mg/kg orally twice daily or sucralfate at 12mg/kg orally twice daily reportedly increases the healing rate to 67.5% and 73% respectively. Both sucralfate and misoprostol are unlicensed in horses, and misoprostol should be handled with care as it poses a significant risk to pregnant women and animals.

The belief that glandular ulcers require acid suppression to heal is challenged by a UK study where misoprostol monotherapy was superior to combined omeprazole/sucralfate for both mucosal healing and improved clinical signs10. The jury is still out on the most appropriate treatment for this disease, but it is likely that the optimal treatment strategy will vary from horse to horse, depending on the exact underlying aetiology, which is unfortunately not something that we are able to discern yet.

The inconsistency in response to oral omeprazole has led to the development of a long-acting injectable formulation. This formulation maintains the gastric pH consistently above 4, for between 4 to 7 days. In the pilot efficacy study, 22 out of 22 horses with ESGD and 9 out of 12 horses with EGGD achieved complete healing at day 14 after treatment with 2g of the 100mg/ml injectable omeprazole on days 1 and 711.

Likely due to superior acid suppression, better resolution of ESGD is reported after four weeks of injectable treatment compared to oral therapy12. This formulation is available from BOVA UK, a veterinary specials manufacturer, for use under the cascade. It is notoriously viscous and difficult to inject if not warmed to body temperature, and can lead to spectacular injection site reactions in a few cases.

With the variety of treatment options now available, no “one size fits all” approach to the treatment of EGUS exists. I adapt the treatment strategies I use depending on factors such as the horse’s signalment, management and workload, affordability of treatments, severity and depth of lesions, clinical signs, comorbidities and whether I will have the opportunity to re-scope, among others.

A population of horses that has been largely ignored in the literature is the one that fails to respond to the aforementioned treatments. Patients that show improvement at follow-up endoscopy may simply require a longer course of treatment, with glandular ulcers often requiring up to eight weeks of treatment. Patients that either fail to respond, or deteriorate in the face of treatment, pose a more difficult challenge.

One option would be to simply prolong the course of treatment, but this may not be appropriate in all cases. Omeprazole is also not without deleterious effect. Concurrent administration of omeprazole and phenylbutazone has been associated with an increase in severe intestinal complications in horses, including large colon impaction, small colon impaction, colic, diarrhoea, necrotising typhlocolitis and necrohaemorrhagic enterocolitis13. Omeprazole also has the potential to impact equine digestion in that it changes lipid, protein and mineral metabolism14, and it significantly decreases calcium digestibility15.

While the effects of these changes are unlikely to be significant for short-term treatments, longer-term effects have not been studied. With long-term treatment in humans, bone density decreases and renal function deteriorates, leading to an increase in creatinine concentration or, more rarely, even acute renal failure.

In horses, creatinine and uric acid are statistically significantly increased within 11 days of omeprazole treatment14. This is a particular concern in patients also treated with NSAIDs. In humans and dogs, omeprazole treatment also significantly alters the faecal microbiota and increases the incidence of Clostridioides difficile enterocolitis. While this significant alteration in microbiota could not be demonstrated in healthy horses16,17, the effect of omeprazole on the mucosal microbiota of horses with EGUS, and in particular those that deteriorate in response to conventional therapy, has not been evaluated.

We don’t know why a small number of horses experience worsening of gastric ulcers with acid suppression, but plausible theories include failure to adequately suppress acid production with portal hypergastrinaemia and intermittent hypersecretion, and changes in mucosal bacterial populations favouring volatile fatty acid (or other corrosive chemical) production.

For ESGD treatment failure, it is appropriate to consider strategies to improve acid suppression in such cases. These include administering 2mg/kg or 4mg/kg omeprazole in a fasted state, splitting the 4mg/kg dose and administering 2mg/kg twice daily, changing the proton pump inhibitor to esomeprazole, or using the injectable long-acting formulation6,18.

In line with the European College of Equine Internal Medicine consensus statement guidelines, horses that fail to respond to the aforementioned first-line treatments for EGGD should be further investigated with mucosal biopsies, and additional treatment strategies considered based on the results. Additional treatments to consider where first-line treatments have failed include corticosteroids for patients with lymphocytic or other inflammatory infiltrates and antibiotics where mucosal bacterial invasion can be demonstrated. Any such treatments should be undertaken with due consideration for the risks and benefits of the treatment, and the avoidance of antibiotic overuse1,6.