13 Oct 2020

Fleur Whitlock, Richard Newton and Adele Williams discuss the present status of this issue, prevention and treatment protocols, and ensuring owner compliance.

This article will provide an update on the present situation with equine influenza (EI) in the UK, why it’s important for all equine vets to keep up to date on this, and the message we should be giving to horse owners, societies, associations and sports horse governing bodies.

This article covers:

For most of us this time last year, before we knew anything about COVID-19, the UK equine influenza (EI) outbreak was a pretty big deal.

We all moved to persuading our clients to take up six‑monthly EI boosters; it was required by some of the equine sport governing bodies.

Things settled down and the outbreak came under control. Life in the equestrian world returned to normal (well, at least until the COVID‑19 lockdown).

However, most vets and horse owners have gone back to annual EI boosters, since the requirements of many equestrian bodies have gone back to what they were before.

As it turns out, evidence summarised and presented in this article recommends we should actually be sticking to six-monthly boosters after an initial vaccine course, to stand the best chance of avoiding another EI outbreak like the one we witnessed in 2019.

This article covers:

Equine veterinary surgeons and stakeholders are encouraged to remain up to date with infectious disease reports, and multiple initiatives are in place to enable this. These surveillance initiatives were previously based at the AHT and have since continued to be supported by the UK equine industry.

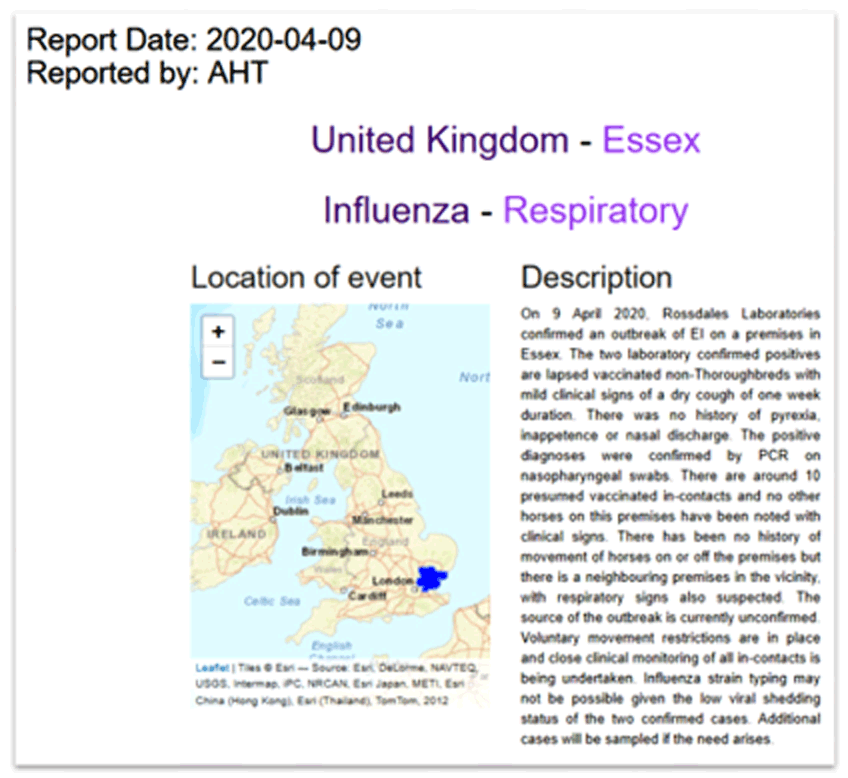

The International Collating Centre (ICC), supported by the member bodies of the International Thoroughbred Breeders’ Federation, actively and passively acquires and collates equine infectious disease outbreak information from multiple sources around the world, and issues real-time interim bulletins that are emailed to subscribers with embedded links to individual outbreak reports (Figure 1).

The ICC also has an interactive website and issues a quarterly summary report, which together provide multiple ways to view international equine infectious disease data.

EI surveillance was carried out at the AHT for nearly 40 years, with the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB) funding free laboratory testing of suspect cases of EI at the AHT’s diagnostic laboratories.

This scheme enabled veterinary surgeons to sample horses with clinical signs that may be indicative of EI, enabling a prompt diagnosis with accompanying advice for prevention and control of an outbreak provided by the AHT’s epidemiology and disease surveillance team.

It is hoped this scheme and EI surveillance will be resurrected and again supported by the equine industry in the near future.

An EI-specific interactive website, Equiflunet, is also available and contains epidemiological information about EI outbreaks in the UK and worldwide. To receive immediate notification of an equine influenza outbreak, UK‑based veterinary surgeons can sign up to a free text messaging alert service, Tell-Tail, sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim (Figure 2).

For a retrospective review of the previous three months of infectious disease outbreak reports, veterinary surgeons can sign up to receive the Defra/AHT/BEVA Equine Quarterly Disease Surveillance Report. UK national laboratory data and disease outbreak information are summarised and reported quarterly, giving a unique insight into equine disease occurrence in the UK.

This report also includes informative and topical articles on infectious diseases and the latest news highlights, including key industry announcements (such as vaccine availability and important outbreaks to be aware of).

Details of how to register to receive these alerts can be found in Panel 1.

During the first half of 2019, the UK and Europe saw an increased level of EI activity.

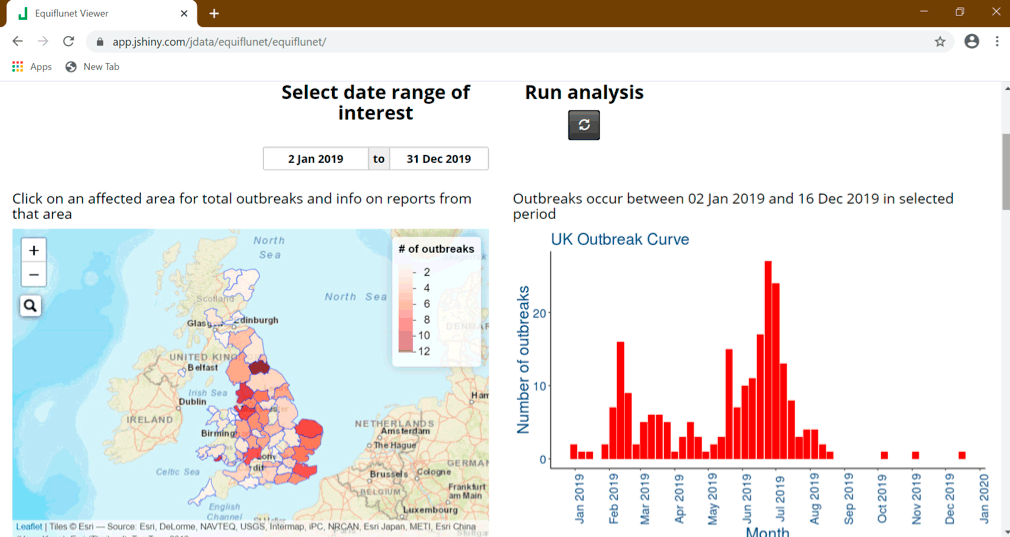

During all of 2019, the UK had a total of 229 equine premises reported to be infected with EI by laboratory testing (Figure 3a); it is suspected many more premises were affected with EI, but were not confirmed.

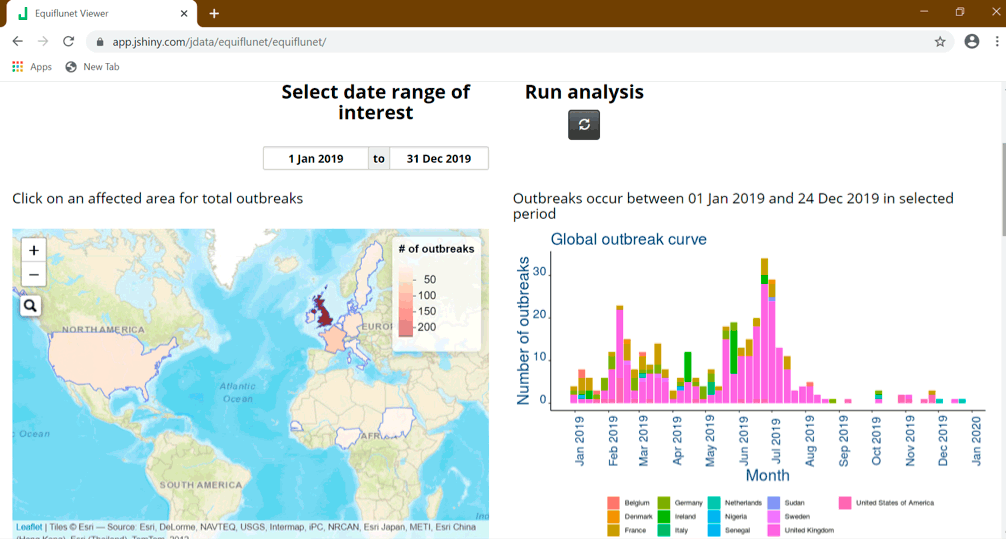

Sources of outbreak reports internationally are predominantly obtained through the ICC.

Sequence analyses of EI viruses recovered in multiple countries in Europe during 2019 confirmed a Florida clade 1 strain was consistently involved. Reasons for the different extents of increase in EI activity in each country in Europe will be country‑specific and epidemiological investigations into the EI situation during 2019 in Great Britain are being undertaken.

The latter half of 2019 saw a gradual reduction in EI reports and have been at a much lower, expected level. During 2020 (up to 17 August), the UK has reported three further outbreaks; France has reported nine outbreaks, the Netherlands six outbreaks, Germany four outbreaks, and Belgium and Estonia each one outbreak, while Ireland reported several premises affected in January 2020.

In the rest of the world (Figure 3b), the US has reported EI is endemic, with 22 outbreaks reported during 2019 and 11 outbreaks reported during 2020 (up to 17 August); however, these numbers are thought to be an under‑representation of the true figures.

West Africa reported an exceptionally high number of EI cases from December 2018, with diagnosis being very challenging due to limited resources available and many cases being suspected rather than laboratory confirmed. A high fatality rate was reported and during April 2019, more than 62,000 equids were thought to have died.

Such reports demonstrate the potential catastrophic effects of EI affecting a naive population with limited resources and capabilities for control and prevention.

Vaccination is used as the main means of protecting against EI and is mandatory in some equestrian disciplines, such as horse racing.

The aim of vaccination is twofold – to protect the vaccinated individual from developing disease and limit the spread of infection.

How, then, should we use vaccination in response to an epidemic of infection such as was seen developing in 2019?

To help answer this question, EI researchers have used mathematical models of infectious disease outbreaks, which are useful in the development and evaluation of disease prevention and control measures (Daly et al, 2013).

Early mathematical models to look at the effects of vaccination showed, as expected, a dramatic reduction in the occurrence of outbreaks among groups of vaccinated horses. It also somewhat surprisingly predicted that, in vaccinated populations, more than 80% of EI outbreaks fizzle out with less than 5% of the population being infected – and these may not be readily detected.

The consequence of this is that, when EI does occur and is detected, it is more likely this is part of a larger outbreak and veterinary advisors need to plan a response accordingly. Part of that response involves a decision about how frequently a vaccine should be given.

Further modelling demonstrated reducing the interval between vaccinations for horses two years of age and older – from one year (annual) to six months (twice‑yearly) – significantly reduced the risk that introducing an infected horse into a premises would result in a large outbreak.

This is especially important when heightened virus activity is evident in the general horse population, as was the case in the UK in early 2019.

Another consideration has been regarding the impact of dealing with a strain of EI virus that’s not fully covered by the present vaccine. However, mathematical models reveal that although the effects on individual animals may not be too dramatic, when scaled up to the population level they can result in a significantly increased risk of an epidemic occurring – hence the advice to use vaccines containing the most relevant strains to those causing the outbreak.

It is important to stress mathematical modelling studies do not replace experimental and epidemiological studies, which test the effects of vaccination with a live virus infection under controlled conditions and investigate field outbreaks, respectively. However, these models have been useful in confirming observations, conclusions and recommendations made in these other studies.

EI vaccines induce protective antibody and experimental studies show these decline over time, such that vaccinated horses are less well protected at 12 months versus 6 months after booster vaccination.

Field studies have identified EI outbreaks where risk of disease in vaccinated horses increased with time since last vaccination (Newton et al, 2000; Barquero et al, 2007; Gildea et al, 2018), with conclusions drawn that use of six-monthly – rather than annual – boosters would improve preventive measures (Gildea et al, 2011).

As a result of all these findings, booster vaccination of horses at six-monthly intervals continues to be strongly advised if a repeat of 2019 is to be avoided.

Even before the 2019 EI epidemic, veterinary epidemiologists at the AHT were proposing an evidence-based revision to vaccine schedules, following discussions about the perceived widespread irregularities between vaccine requirements for different equestrian bodies and to those in the vaccine data sheets.

Concerns existed that EI vaccination was beginning to be regarded as merely a requirement of competition; however, the 2019 situation has reminded us of their necessity to ensure animal welfare and successful, uninterrupted competition seasons.

Table 1 outlines this proposed harmonised schedule, with the appropriate scientific justifications. This would require adoption by all equestrian bodies, but would improve clarity for horse owners and veterinary surgeons, and would consequently improve take‑up and compliance with EI vaccination schedules.

| Table 1. Proposed harmonised schedule, with appropriate scientific justifications | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vaccine | Proposed new dosing interval | Scientific justifications |

| Primary course: V1 to V2 interval | 21 days to 56 days | Manufacturers’ data sheet recommendations are four weeks to six weeks; this proposed schedule allows some flexibility around this. The upper end is considered much more biologically plausible than the existing British Horseracing Authority (BHA) rules of 92 days. |

| First booster: V2 to V3 interval | 120 days to 185 days | Manufacturers’ data sheet recommendations are a five-month interval after V2. This change would shorten the interval from the existing BHA rules of 150 to 215 days, therefore addressing the “immunity gap” that is recognised with longer intervals between V2 and V3, and which has previously been shown to be a period of high risk for infection. |

| Boosters | Six months | Manufacturers’ data sheet recommendations are 12 months; however, studies to generate these recommendations are performed under scientific conditions, rather than in the equine population. Studies have shown horses that have received a more recent vaccine will have a more optimal level of immunity. Due to antigenic drift of the EI virus, mismatches between vaccine and field strains are present, and more regular vaccination is an attempt to counteract this phenomenon while manufacturers are not regularly updating vaccines to account for this. |

Other factors to consider for harmonisation include accepted periods from date of last vaccination to date of competition, and approach to errors noted in passports during official inspection.

In the future, it is hoped the development of digital platforms – such as the Central Equine Database and Equine Register’s Digital Stable facility – will ease passport checking, with confirmation of adherence to the vaccine requirements in individuals assessed prior to arrival at a competition.

The confirmation of adherence can also be automatic, rather than reliant on human calculations. It would also be securely validated, ensuring correct data is provided by owners, including vaccination information and horse and owner identification.

To ensure the future success of vaccine schedule harmonisation, the equine industry would need to decide if it is willing to adopt a single set of harmonised rules for EI vaccination.

This article has provided a summary of the available EI platforms and how veterinary surgeons can keep abreast of flu outbreaks:

It has also outlined why using vaccines is our first-line defence to protect against clinical signs and spread of disease, and how we should be implementing this. In particular, why a universal move to 6-monthly – rather than 12‑monthly – boosters for adult horses older than two years of age is so critical.

Mathematical models can assess the effect of vaccination on disease outbreaks occurring:

Finally, it considered the proposal for vaccine schedule harmonisation: