12 Nov 2018

Basic care requirements of rabbits and small furries

Kate Forshaw and Livia Benato outline the perioperative and nutritional management required by these animals, with a focus on ferrets and skunks.

More and more rabbits and small furries are being seen in small animal practice as pets.

Owners’ lifestyles and living habits are changing. People work more extended hours, while renting has increased in popularity with rising house prices – and landlords are often more keen to accept smaller pets than a cat or dog. For these reasons, rabbits and small furries are becoming beloved pets, too.

Moreover, client expectations are rising – and the availability of insurance for exotic pets means more can be offered to treat many species. This does not mean vets need to become exotics experts overnight, but it is essential to have a basic understanding of the needs of these species to minimise stress during their hospitalisation and ensure they receive the best treatment possible while at the clinic.

The most common small mammals seen in veterinary clinics generally fall into three categories – herbivores, such as rabbits, chinchillas and guinea pigs; omnivores, such as rats, hamsters, mice and skunks; and carnivores, such as ferrets (Table 1).

| Table 1. What they eat: feeding habits | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feeding categories | Animals | Diet |

| Herbivores | Rabbits, guinea pigs, chinchillas and degus | Herbivores need a diet high in fibre and low in energy. Guinea pigs’ diet can generally contain a lower percentage of fibre (10% to 16%) compared to rabbits (20% to 25%). The diet of rabbits, guinea pigs, chinchillas and degus consists of hay and grass, a small amount of species-specific pelleted food, and fresh vegetables (the species should be considered to decide the type and amount of vegetables required). Guinea pigs also require dietary supplementation with vitamin C (up to 50mg/kg to 100mg/kg per day in stressed or sick animals). |

| Omnivores | Rats, mice, hamsters and skunks | Rats, mice and hamsters need a diet containing 16% protein and 5% fat. Their diet consists of pelleted food, some fresh vegetables and fruits offered daily, and a small source of proteins once a week (the amount of proteins should be reduced in senior animals). Skunks are opportunist omnivores and their diet consists of a variety of food items, composed of two-thirds of a source of protein, one-third vegetables and small amount of fruits (5%). Calorie content needs to be carefully considered, as they can easily become obese. |

| Carnivores | Ferrets | Ferrets are strictly carnivores and unable to digest fibres efficiently. They need a diet high in animal protein (35% to 40%) and fat (15% to 20%). Specialised commercial pelleted foods are available that are considered nutritionally healthy for this species. |

They can be further grouped – in terms of their requirements for hospitalisation and perioperative treatment – into prey species, such as rabbits and rodents; and predator species, such as ferrets and skunks (Figure 1). This article will explore the management of the latter group.

Rabbits and rodents

Rabbits and rodents are prey species, and can be susceptible to stress, which can affect many aspects of their well-being. A key factor is minimising or preventing this while hospitalised.

Rabbits and rodents should be kept separated from any predators; a separate ward for exotics would be ideal. However, even with a dedicated exotics ward, it is important to bear in mind some animals, such as ferrets and skunks, should not be hospitalised there as they can leave behind a strong smell long after they have gone. This would cause unnecessary anxiety to the prey species – preventing them from exhibiting normal behaviours, and making their assessment and treatment more difficult.

If a dedicated area for prey species is not available, it is still possible to take a note of the species being hospitalised each day and keep them separated, considering their needs.

Rabbits and rodents should be hospitalised in appropriately sized kennels, depending on their body size, and provided cardboard boxes and tunnels to hide in. They also benefit from environmental enrichment and mental stimulation, so toys, boxes and tubes to run through should be provided as well (Figure 2).

Where possible, owners should be encouraged to bring in the companion – especially for animals that live in groups, such as rabbits or guinea pigs. This will minimise the stress associated with social separation and reduce problems during the reintroduction at home once discharged.

This works well in most cases, but patient identification must be certain (record the animal markings or use paper collars, for example). It can prove difficult in cases where monitoring faecal output and appetite are of utmost importance; however, the companions can be temporarily separated while monitored.

Newspaper, hay, and stripped newspaper or kitchen tissue can be used for bedding and nesting material for smaller pets, such as rats and hamsters. It is worth noting chinchillas and degus also require a dust bath during hospitalisation – providing they do not have skin wounds – which is essential for their fine coats and mental well-being.

Concerning feeding, the authors often encourage owners to bring in the animal’s usual food to prevent stomach upsets and provide a more familiar environment. However, good-quality hay and an array of food items – such as pelleted food for omnivores and herbivores, and greens and fruits – should be available depending on the patient’s nutritional requirement.

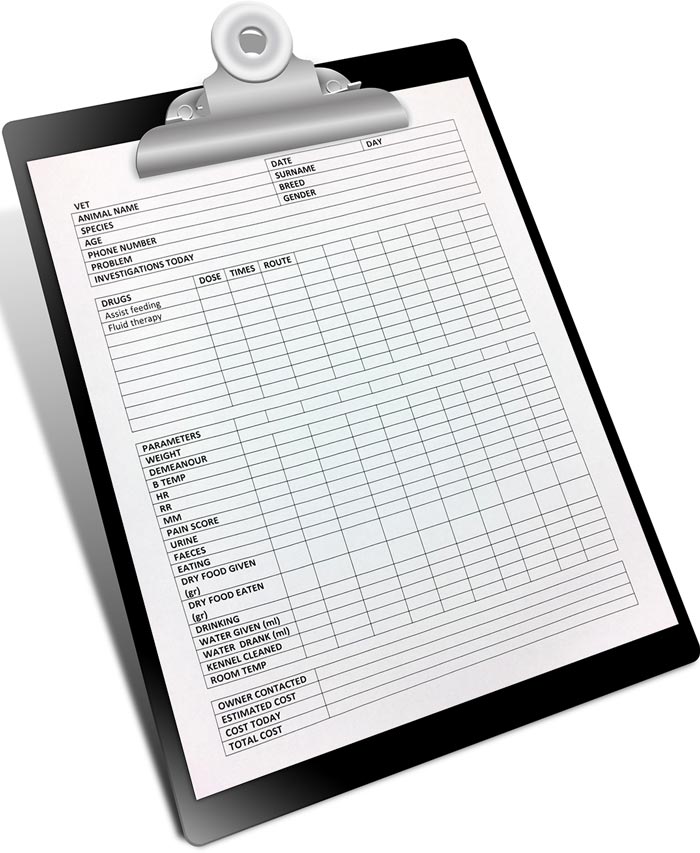

Water and food intake should be measured daily, as it can be difficult to observe how much the patient has had. Water can be measured using a syringe, pelleted food can be weighed, or the individual pellets counted out. Everything should then be recorded on the hospitalisation form. Fruit and vegetables offered can be recorded as well (Figure 3).

Assisted feeding may be needed to support the patient, stimulate appetite and promote intestinal motility. These days, several brands of critical care formulas are available on the market, depending on the nutritional requirements of the patient. They are all nutritionally balanced and easy to mix into a syringe feed, which is often taken quite keenly by the patients, usually with minimal restraint.

Ferrets and skunks

Ferrets and skunks are masters of escape, so it is important to hospitalise them in a secure environment. They can be kept in standard stainless steel kennels and provided with a nice box in which to sleep. They love a nice blanket to snuggle in (Figure 4), so a selection of small soft blankets and fleeces should be available.

A corner litter tray should also be provided for easier cleaning and maintenance of the kennel. During hospitalisation, even ferrets and skunks still benefit from mental stimulation, so cardboard tubes and toys should be supplied.

Predator species, in general, can exhibit aggression over food when handled, so it is important to clearly mark behavioural traits on the hospitalisation chart to prevent painful bites and stress of the patient.

As for any other inpatient, they should be weighed daily (Figure 5) and any changes taken into consideration, as this could lead to changes in the medical and supportive treatment.

Many practices tend to feed either a cat or dog food. This is considered fine in the short term; however, it would be better to offer a species-specific diet where possible, as this will meet the nutrients and energy requirement for such active small mammals.

Pelleted versions are available in reasonably small bags that can be kept for a while. Otherwise, it is possible to ask owners to provide some of the animal’s usual food to prevent intestinal upsets and waste of unused food.

For anorexic animals, assisted feeding should be provided using critical care formulas for either carnivores, in case of ferrets, or omnivores, for skunks. They are easy to mix up and feed using a syringe, and most patients tend to take it quite well.

Ferrets can be messy in the hospital environment, so care should be taken to regularly check water bottles and bowls, and keep them clean and topped up.

Perioperative care

Optimal perioperative care is an essential aspect of the management of small furries, and it is paramount for a successful outcome.

During hospitalisation, it is crucial to keep an accurate record of the inpatient (Figure 3). Bodyweight should be taken at least daily, while temperature, pulse and respiratory rate (Table 2) should be recorded every four hours unless otherwise indicated.

| Table 2. Temperature, pulse and respiratory rate of the most common small mammals | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Body temperature | Heart rate (bpm) | Respiratory rate (bpm) | |

| Rabbit | 37.6°C to 39.5°C | 180 to 250 | 30 to 60 |

| Guinea pig | 37.6°C to 39.5°C | 190 to 310 | 90 to 150 |

| Chinchilla | 37°C to 38°C | 100 to 150 | 40 to 80 |

| Degu | 37°C to 38°C | 100 to 150 | 75 to 80 |

| Rat | 37.2°C to 38.5°C | 250 to 450 | 71 to 150 |

| Hamster | 37.5°C | 280 to 412 | 36 to 127 |

| Mouse | 37.5°C | 500 to 600 | 120 to 250 |

| Ferret | 37.8°C to 38.8°C | 200 to 350 | 33 to 40 |

| Skunk | 33.3°C to 38.5°C | 140 to 190 | 25 to 50 |

Care should also be taken when planning a procedure to ensure all equipment is prepared and laid out ready in advance, and the patient is not disturbed more than necessary to prevent any added source of stress.

Ferrets and skunks need to be starved before surgery as they can vomit and regurgitate while under anaesthetic. However, due to their high metabolism, they do not need to be starved for as long as cats and dogs – four to six hours prior to surgery is generally adequate.

Rabbits and rodents, on the other hand, do not require starving as, due to the anatomy of their stomach, they cannot vomit. However, it is advisable to either check their mouth or remove the food half an hour before the procedure to reduce the risks of food in the mouth that could block the airways during intubation.

Maintaining body temperature perioperatively is also essential. Care must be taken when preparing these patients for surgery that the clipped area is kept to a minimum and they are not made too wet with the surgical prep solutions, as they can lose a significant amount of heat from the body in a short time.

Flat heat mats can be plugged into the mains and do not rely on bodyweight to warm up. In the authors’ opinion, the most effective ways for maintaining body temperature are wheat bags warmed in a microwave, as they can be used almost like sandbags to position the patient and mould around them. These should not be too hot; they should be covered with a towel or a blanket and checked regularly to prevent thermal burns of the skin.

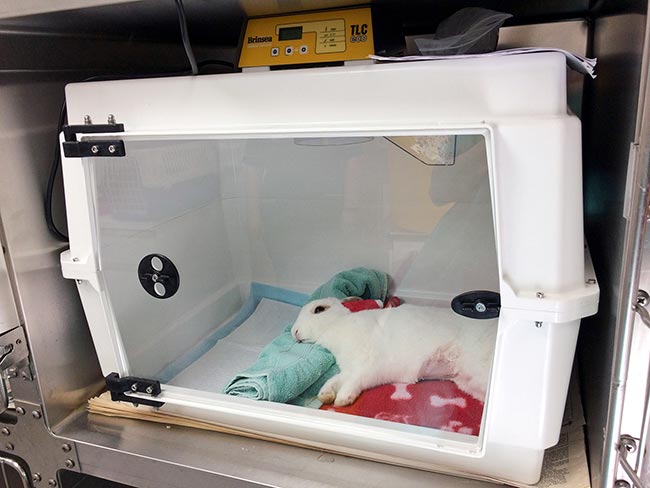

If an incubator (Figure 6) is not available at the clinic, microwavable heat pads are a great alternative as they can provide a constant source of heat for at least four hours postoperatively and cannot be chewed through. However, other options are available – such as hand warmers, thermal blankets, temperature management systems, bubble wrap, or simply increasing room temperature.

The postoperative period in small mammals is a critical time. So, to prevent risks, an inpatient nurse should be allocated to the recovery of these patients. They should be monitored regularly – not only until the animal is fully conscious and able to control the body temperature, but also until they can eat and they start passing faeces. The animal should also be assessed for pain and further analgesia provided if necessary.

Although dedicated pain scales for all these species are not available, numeric or visual analogue pain scales can be useful assessment tools. For rabbit patients, the rabbit grimace scale is available.

Conclusion

Care of these patients should not be approached in the same way as other companion pets, such as cats and dogs; small mammals require a little more thought and, possibly, time.

However, no reason exists why they cannot be successfully hospitalised and cared for without little planning and discussion. Communication within the vet/nursing team and accurate record keeping are essential.

These patients are very rewarding to vets and nurses, and it is a real joy to look after and observe them.

References

- Dragoo JW (2009). Nutrition and behavior of striped skunks, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice 12(2): 313-326.

- Meredith A and Johnson-Delaney C (2010). BSAVA Manual of Exotic Pets (5th edn), BSAVA, Gloucester.

- Quesenberry KE and Carpenter JW (2012). Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery (3rd edn), Saunders, Philadelphia.

- Thatcher E (1980). Veterinary care of ferrets, raccoons and skunks, Iowa State University Veterinarian 42(1): 27-36.

- Teare JA (2013). Mephitis mephitis. No selection by gender. All ages combined. Standard International Units 2013 CD.html, ISIS Physiological Reference Intervals for Captive Wildlife: a CD-ROM Resource, International Species Information System, Minneapolis.