4 Nov 2022

Guen Bradbury emphasises the importance of working with owners to understand and resolve issues in these popular pets.

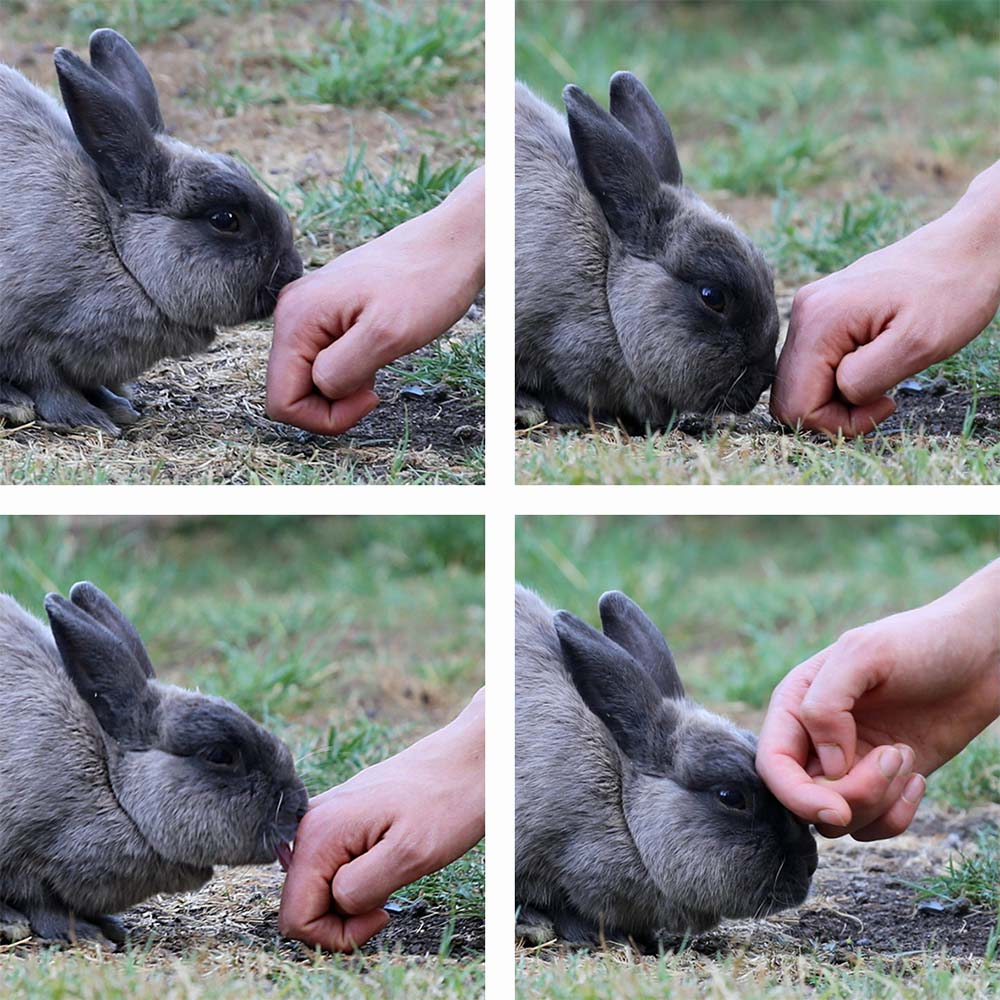

Figure 4. Rabbits respond really well to positive reinforcement training.

The UK has 1.5 million rabbits. In a recent survey, 43% of those rabbits showed at least one behaviour that the owner didn’t like.

Unwanted “problem” behaviours don’t just cause a nuisance to the owner – they can indicate the rabbits are experiencing poor welfare and can also can cause a breakdown in the human-animal bond.

And this is serious. When that bond breaks down, owners are less likely to interact with their rabbits frequently, less likely to notice signs that indicate ill health, and are less likely to seek and pay for treatment.

Behavioural problems often contribute to health problems. And they severely affect rabbit welfare.

What do owners typically do if their rabbit shows a behaviour that they don’t like? In the 2016 PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report, owners were asked how they would find help with their rabbits’ behaviour. Some owners (14%) said they wouldn’t bother. About a third (38%) said they would look online. But half of the owners said they would ask a vet professional.

And that is why we, as vets, need to know about rabbit behaviour: because we are the first port of call for a large number of rabbit owners.

Why do rabbits show behaviours that owners don’t like? The majority are caused either by bad husbandry or by bad interactions.

This actually makes diagnosing the causes of a problem behaviour fairly simple – a good history can alert you to aspects of the rabbits’ husbandry that are imperfect. You can also ask about how the owner plays with their rabbits and how they show affection; this gives you information about interactions.

When we think of unwanted behaviours, we typically think of aggression, fearfulness, destruction or inappropriate elimination, but actually, owners may dislike a different behaviour entirely.

In the 2016 PAW report, the “problem behaviours” that owners reported most frequently were thumping of the hindfeet, and biting of the bars of the hutch or cage. These are clear signs that these rabbits are fearful, anxious, bored and frustrated. And when owners tell you about these signs, it is a great opportunity to give some advice that can really improve their rabbits’ welfare.

So, let’s think about what a rabbit needs, and then we can think about what good husbandry and good interactions mean to a rabbit.

Rabbits were domesticated fairly recently (about 1,200 years ago, in comparison to 12,000 years for cats and more than 40,000 years for dogs). So that means that the motivations of a pet rabbit are essentially the same as those of a wild rabbit.

The key thing to remember about wild rabbits is they are eaten by almost everything – they are the main source of food for almost 30 species in their native habitat. So almost everything that a rabbit does is governed by its strong evolutionary motivation not to be eaten.

When rabbits are forced into situations where they think they are about to get eaten, they feel very stressed. And this explains why being kept alone and being picked up, two of the most common causes of poor welfare in rabbits, are so stressful to them.

If you’re a rabbit, why are you so desperate to be with other rabbits? Well, if you’re trying not to be eaten, living in a large group means that the chance of you becoming prey is lower. And if a predator comes near, there is a very high chance that at least one of your rabbit companions will spot it and signal, alerting the whole group and allowing them to escape.

If you’re a rabbit, why don’t you like being picked up and cuddled by humans? Humans are a predator species. You know that if you’re picked up by a predator species, you’re probably not going to survive (Figure 1).

We should think about a rabbit’s natural environment when we consider how we keep it. Good husbandry, for a rabbit, means companionship, as mentioned previously. It means a diet that is almost entirely grass or hay, if grass isn’t available. It means access to the outdoors, for vitamin D, for expression of natural behaviours including grazing, and for stimulation (Figure 2).

Good interactions for a rabbit mean not being picked up or at least being picked up as rarely as possible. Good interactions are those where the rabbit has a choice rather than those where the rabbit is forced to interact. They include the owner offering a hand and the rabbit lowering its head to be stroked (Figure 3), clicker training, giving food rewards, and sitting in close proximity.

Unlike many other interactions (such as picking rabbits up to “cuddle” them or turning rabbits on their back to “trance” them), these are rewarding for both the owner and the rabbit. And these build trust rather than fear, and they provide the foundation for improving behaviour, and improving the relationship between the owner and their pets. Most problem behaviours can be resolved at least partially by improving the rabbits’ husbandry and changing the owner’s interactions with the rabbit.

However, some behaviours become habitual or ingrained when a rabbit relies on them to cope with a situation, and even when the situation is improved, the rabbit may continue to show these behaviours.

This is commonly seen with rabbits that show aggression when their owners pick them up. Even if the owner stops picking the rabbit up, the rabbit still will not trust the owner, and may show aggressive behaviours when the owner goes near to them.

When a rabbit shows an unwanted behaviour habitually, the owner needs to change the rabbit’s motivation. This is where training comes in.

Rabbits respond really well to positive reinforcement training, usually with food rewards (Figure 4). Advise owners to use normal rabbit pellet food.

Adult rabbits should never be fed on ad lib concentrate food because they need the physical and behavioural stimulation of eating long fibre. Concentrate food is more palatable than hay and grass, so rabbits will tend to eat more concentrate food than they should.

As the concentrate food needs to be restricted, rabbits are motivated by it, so it can be used as a training reward. Additionally, the pellets are an ideal size for training rewards, and they are nutritionally balanced, so are unlikely to cause gastrointestinal problems. Various resources on rabbit training for owners, vet nurses and vets exist, including the first textbook on the subject of rabbit behaviour.

So, we’ve looked at why vets need to know about rabbit behaviour, the sort of behavioural problems that rabbit owners report, what motivates rabbits and the core of good husbandry.

As a vet or a veterinary nurse, you should now have the basic tools to at least open a discussion about rabbit behaviour with an owner in your clinic.

However, actually taking the discussion forwards to a treatment plan can be somewhat daunting. It doesn’t need to be – the structure for working up a rabbit behaviour case is just the same as that for any veterinary consultation.

Start by checking the signalment of the rabbit. Older rabbits are more likely to have underlying health problems that affect their behaviour. Female rabbits are more likely to show aggressive-type behaviours.

Then, take the history. If in doubt, ask more questions. Try to understand how the owner keeps the rabbit and how they interact with it. It is important to know if the rabbit is allowed or denied companionship of another rabbit. At this stage, you’re probably already able to identify some aspects of the rabbit’s welfare that are poor.

A full clinical exam is vital – rabbits hide disease very well (as you would, if you didn’t want to show weakness to a potential predator). Look for signs of diseases causing chronic pain: dental disease, urinary tract disease, obesity, arthritis or pododermatitis.

You need to treat these conditions before you approach the behavioural problem. Trying to resolve a behavioural problem in a painful or sick rabbit is hard or even impossible.

Then comes the diagnosis. The owner will have told you what they consider to be the problem behaviour and you can discuss with them the factors you think are contributing to it; these will have come from your history and clinical exam. Explain why these factors contribute – don’t just tell the owner that they do.

Owners often feel frustrated when their rabbit is doing something they don’t like, so helping them to empathise with the rabbit will help strengthen the human–animal bond.

Next is treatment. You can make major progress with the rabbit’s behaviour simply by improving its husbandry and helping the owner form realistic expectations. However, some behaviours become habitual or ingrained, so even if the environment is improved, the behaviours may persist. This is when training to introduce new behaviours can be really valuable.

And finally, reassess. No quick fix exists for many behaviour problems and resolution comes from making many small changes. Therefore, it’s really important to check in with owners about two weeks after they have started making changes. Give them a call, have a chat, see what’s been working and check what still needs to change.

As with any behaviour problem, be sympathetic to the owners. The sort of owners who will ask you advice will usually really care about their rabbit and be trying to do the right thing.

Changing their rabbit’s behaviour requires them to change their own, and that is very hard.

Additionally, you can’t give them a quick solution – the owners see changes over a longer period of time. So, guide, discuss, suggest. Don’t dictate or instruct.

Remember, the least successful behavioural modification plan is the one that is not followed.

Vets should care about rabbit behaviour because they care about rabbit welfare and they want to encourage rabbit owners to bring their pets to the vet.

Rabbit behavioural problems are generally fairly straightforward, and respond very well to husbandry and interaction changes.If you have a basic knowledge of what rabbits need, you can give good guidance on how owners can improve rabbit behaviour.

Additionally, if you know what owners can do to change rabbit behaviour and where they can find more information, you can enormously improve the welfare of the rabbits under your care.