14 Dec 2020

Case of splenic haemangiosarcoma in a guinea pig

Mónica Guerrero Méndez discusses the examination, treatment and outcome in this patient, as well as the need to consider this differential diagnosis when investigating abdominal masses.

A three-year-old female guinea pig was presented with a history of gastric disturbances (smaller sized droppings) and abnormal behaviour. On a clinical exam, a large abdominal mass was reported.

On lateral and dorsoventral radiographs, the origin of the mass could not be determined, so an emergency exploratory laparotomy was carried out. The mass was reported to be the spleen, which measured 4cm long by 4cm wide. The spleen was friable to the touch. The rest of the organs appeared grossly unremarkable, without signs of metastasis. Recovery from anaesthesia was unremarkable. A differential diagnosis with haemangiosarcoma was made, which was confirmed by histopathology.

Haemangiosarcoma is not listed among the most common tumours found in guinea pigs – cavian leukaemia, pulmonary neoplasia, cutaneous neoplasia and reproductive neoplasia are the most common. However, it needs to be included in any differential diagnosis when an abdominal mass is found on clinical examination. Hoch‑Ligeti et al (1981) described five primary tumours of the spleen in guinea pigs – only four instances of haemangiosarcomas were reported.

This case report explains in detail the steps to diagnose and treat a possible spleen haemangiosarcoma in guinea pigs. Two months post-surgery, the patient is doing amazingly well.

A three-year-old female guinea pig was presented to the author showing signs of abnormal behaviour; her droppings were also slightly smaller in size, indicating some gastric disturbance.

She was housed indoors with a male guinea pig. Her diet consisted of a mixture of good-quality pelleted food, plus ad libitum, good-quality hay and fresh greens (grass, dandelions, parsley and broccoli); the patient was also supplemented with vitamin C.

The author had examined the guinea pig two months previously, when she was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection and treated with trimethoprim at 30mg/kg by mouth twice daily for 10 days. The patient was already on meloxicam for a chronic dental problem. At the time, she underwent a thorough examination, including palpation of her abdomen, and nothing untoward was remarked.

On clinical examination during the current presentation, the patient appeared alert, her appetite was excellent, hydration status was good and the overall condition was fair. The abdomen was slightly bloated; nevertheless, no deep pain or gas was reported, indicating ileus or colic. The bodyweight was 1,000g.

On abdominal palpation, the right ovary appeared slightly enlarged, indicating a possible reproductive disorder such as cystic ovaries (very commonly reported in this species). However, another moveable large mass of unknown origin (4cm by 4cm) was reported cranially, so a radiograph examination was scheduled for the next day. Another course of trimethoprim at the same dose was started to cover any possible secondary bacterial infection.

Due to economic constraints, haematology and biochemistry were not carried out in this case.

Investigation

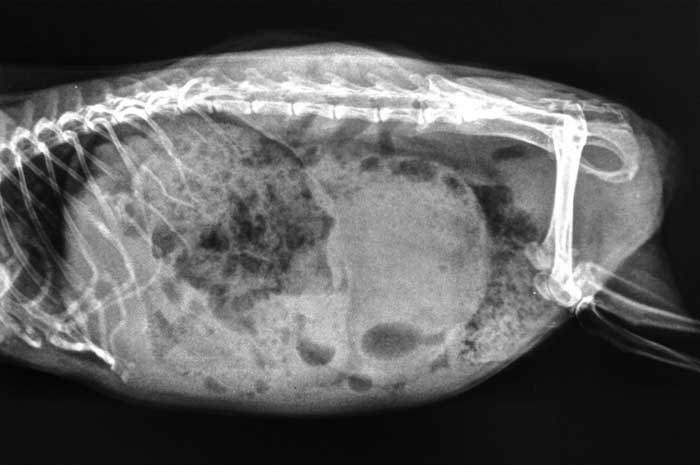

Full-body lateral and dorsoventral radiographs were taken under general anaesthesia (isoflurane in oxygen), and revealed a slightly enlarged right ovary and a large radiodense mass occupying part of the abdominal cavity and pushing the viscera (Figures 1 and 2). A large amount of faeces alongside the intestines and colon was also reported.

The lung fields appeared unremarkable, indicating no signs of metastasis. The patient was in good condition, so an emergency exploratory laparotomy was carried out the same day (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis was consistent with cystic ovaries and a possible tumoural process with no clear origin, but possibly affecting the spleen or the liver.

The prognosis was poor to guarded on the grounds that small mammals are extremely sensitive to major surgical procedures – especially abdominal surgery.

Treatment

Meloxicam at 2mg/kg and buprenorphine at 0.1mg/kg were administered SC and IM, respectively, as premedication. Warm Hartmann’s solution at 50ml/kg was administered SC perioperatively.

A good plane of general anaesthesia was achieved using a triple combination of 0.05ml/kg of ketamine, 0.1ml/kg of medetomidine and 0.05ml/kg of butorphanol, delivered IM and maintained with isoflurane in oxygen at 1.5 per cent via face mask. The skin was aseptically prepared for routine laparotomy.

A large skin incision was made alongside the midline, allowing enough space to investigate the abdominal organs. A very small cyst was reported on the right ovary, otherwise the reproductive tract appeared unremarkable. The cyst was drained and the patient was not neutered to minimise surgery time.

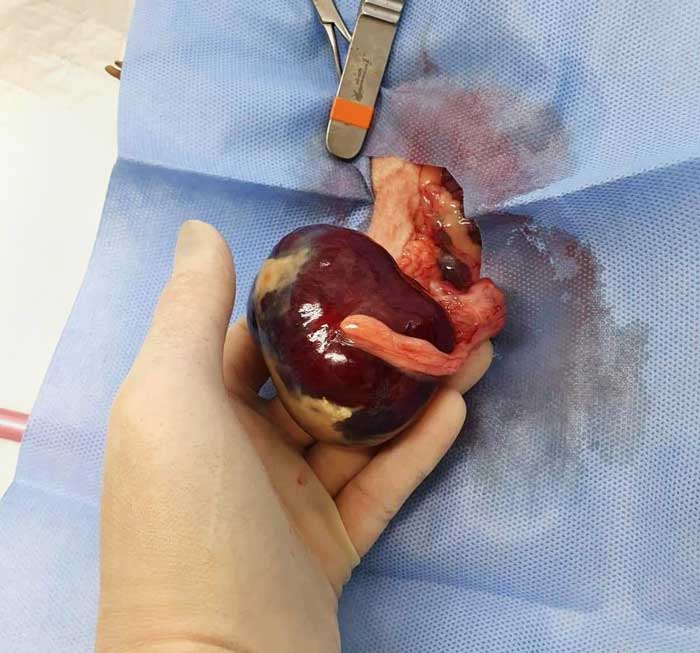

Cranially to the ovary, a large mass of about 4cm by 4cm was reported (Figure 4) and identified as the spleen, occupying approximately 80 per cent of the organ. The surface of the tumour was very friable and vascular, as were the vessels surrounding it; irregularities on its surface were reported in several places.

A splenectomy was carefully performed using 3.0 metric polydioxanone (PDS) to ligate the vessels. The rest of the organs were examined for obvious gross changes of metastasis, but they all appeared normal. Some bleeding was reported intraoperatively, so another 50ml of warm Hartmann’s was administered SC.

The abdomen and skin were closed using a continuous pattern and a subcuticular pattern, respectively, as a single suture layer using 3.0 metric PDS (Figure 5).

The entire splenic tumour, which weighed 200g and measured 4cm long by 4cm wide, was preserved in formalin to be sent to the laboratory for histopathology analysis.

Outcome and follow-up

Recovery from surgery was very fast and unremarkable; the patient started to eat straight after surgery.

Additional analgesia and antimicrobial cover continued with 2mg/kg meloxicam, 0.1mg/kg buprenorphine and 30mg/kg trimethoprim twice daily for another week. Some oozing from the surgical site and a slight nosebleed were reported on recovery, so a vial of 10mg/ml vitamin K was administered IM.

The patient was housed separately from her partner for a week to prevent post-surgery stress and to speed up the recovery. Updates were requested on a daily basis: oozing from the surgical site stopped the first day and no more nosebleeds were reported. Faecal output and appetite remained the same on recovery.

Two months post-surgery, the patient appears healthy, her bodyweight has remained stable, and she is very active and happy.

Histopathology results

A spleen haemangiosarcoma of possible spontaneous or fast-growing origin was revealed in histology. The tumour weighed 200g and was 4cm wide by 4cm long.

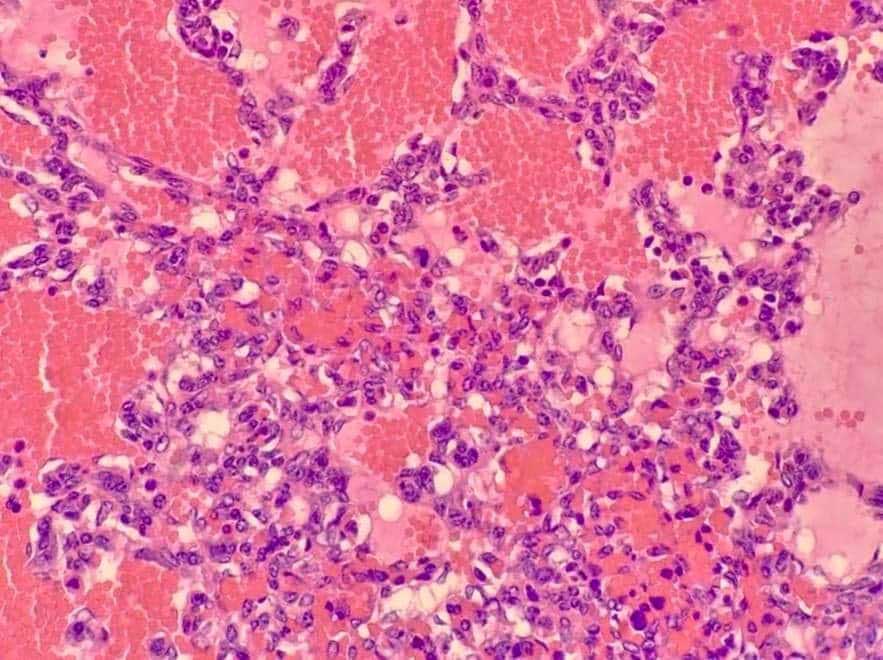

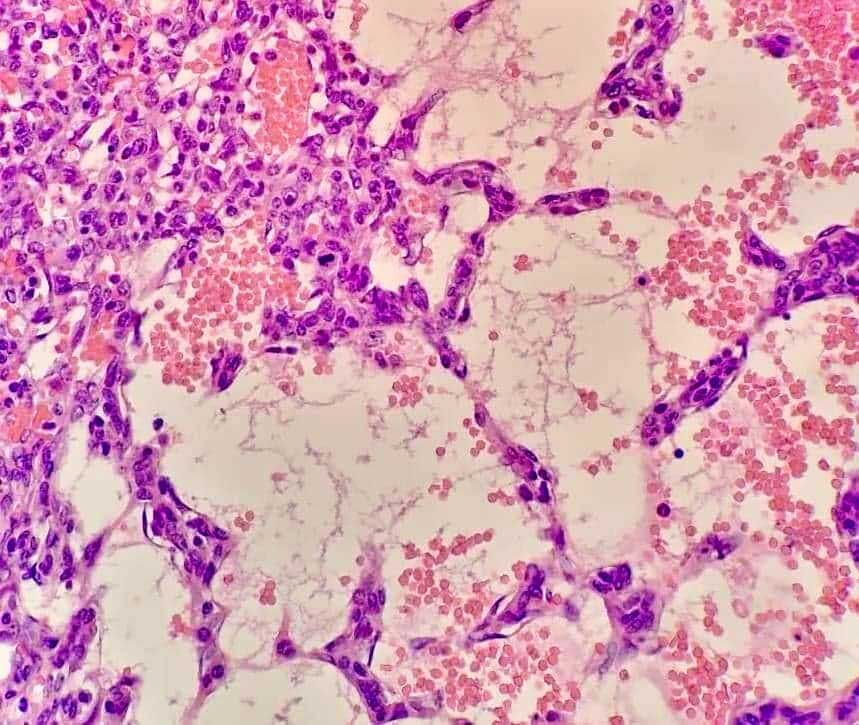

Histologically, the mass consisted of a non‑encapsulated, poorly demarcated malignant mesenchymal tumour. The tumour was composed of loose streams of plump neoplastic endothelial cells organised into irregular blood-filled spaces (Figures 6 and 7). Neoplastic cells showed a small amount of indistinct eosinophilic cytoplasm and a single ovoid to fusiform nucleus with a single, sometimes prominent, hyperchromatic nucleolus.

Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis were moderate, and occasional mitotic figures were observed. Occasionally, large areas of fibrin and clotted blood were present, which were largely necrotic (infarction).

This kind of tumour is very rare in guinea pigs, but still needs to be considered when doing a differential diagnosis on any abdominal mass.

Prevention

Spleen tumours are very rare in guinea pigs, so little information exists on prevention.

Discussion

Guinea pigs are hystricomorph rodents – “porcupine-like”. Hystricomorph rodents have long gestation periods, and all teeth are open‑rooted and grow continuously; they are hindgut fermenters and strict herbivores.

Diet must be high in fibre, and a mixture of fresh greens and hay or grass ad libitum. Coat colours include white, red, tan, brown, chocolate cream, golden, beige, lilac and black.

Guinea pigs are very social animals and are best housed in small groups or pairs.

The two most common pathologies affecting guinea pigs are neoplasias and endocrine diseases. Among the most common neoplasms are:

- Cavian leukaemia (B-cell leukaemia) associated with an endogenous retrovirus of the lymphopoietic system. In this kind of tumour, organs such as the spleen or liver can become enlarged, as was the case with this patient.

- Pulmonary neoplasia, which can be mistaken for metastatic cancer, abscesses or granulomas.

- Cutaneous and SC neoplasia, generally benign tumours such as trichoepithelioma.

- Reproductive tract neoplasia, in which ovarian tumours are most commonly unilateral and observed in females older than three years of age (as in this case). Ovariohysterectomy is the treatment of choice for this kind of tumour; however, most of the time they are benign. In this case, the author did not neuter the patient since the ovarian cyst was very small, and she aimed to minimise surgical time and optimise survival rate. Mammary tumours are common, too, and can be reported in both males and females. Adenomas, fibroadenomas and adenocarcinomas are the most commonly reported.

In this case, the patient had a large abdominal mass that needed investigation. The patient was bright and responsive, with overall good body condition and good appetite. On the radiographic exam, the mass was pushing the viscera. The chest appeared clear and without signs of metastasis.

A differential diagnosis of a possible liver tumour was made, given the size of the mass, although an exploratory laparotomy revealed the organ affected was the spleen. The tumour was similar to that described by Thompson et al (2016).

The spleen in female guinea pigs is generally larger than in males, but in this case it was too large to be considered normal (4cm wide by 4cm long and weighing 200g).

Only a few cases of splenic haemangiosarcoma have been reported worldwide, so an initial differential diagnosis suspecting an haemangiosarcoma was made, which was confirmed by histology.

Hoch-Ligeti et al (1981) described five primary tumours of the spleen in guinea pigs: glomerate vascular tumours, sinusoidal haemangioendothelioma, chondromas, lipomas and only four haemangiosarcomas.

General anaesthesia was satisfactorily achieved using a triple combination of domitor, ketamine and butorphanol – a combination the author had not previously used in this species. Recovery from general anaesthesia and surgery was quick and smooth, and the patient started to eat straight away.

However, some blood disturbances were reported in the recovery, such as a small nosebleed, which stopped almost immediately, and some oozing from the surgical site – both of which the author related to the splenectomy; vitamin K at 10mg/ml was administered IM to control any post-surgery clotting problems.

Once the animal was stable and eating, she was sent home. Systemic antibiotics (trimethoprim) and a combination of pain relief (meloxicam and buprenorphine) – to avoid postoperative anorexia and gastric disturbances – were continued for one week.

Two months post‑surgery, the patient is doing brilliantly: she is back with her companion, and very active and lively. Three monthly follow‑ups have been scheduled.

Conclusion

Splenic haemangiosarcomas are very rare in guinea pigs, but need to be included in any differential diagnosis when an abdominal mass is found on clinical examination. Not much information exists on splenic haemangiosarcomas in this species; in this specific case, considering the friability of the organ, it would have been dangerous to have left it untreated, since it could have led to a spontaneous spleen rupture, consequent haemorrhage and, therefore, the possibility of spontaneous death.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges Alejandro Suárez‑Bonnet, DVM, MVetMed, PhD(Hons), DipACVP, MRCVS – lecturer in comparative pathology at the RVC department of pathobiology and population sciences – for kindly carrying out histopathology in the sample, as well as taking the pictures (used with permission).

She also acknowledges Ross Brown – professional proofreader, business writer and editor – for kindly proofreading this article.

- Some drugs in this article are used under the cascade.

References

- Hedley J (2020). BSAVA Small Animal Formulary Part B: Exotic Pets (10th edn), BSAVA, Gloucester.

- Hoch-Ligeti C et al (1981). Primary tumors of the spleen in guinea pigs, Toxicologic Pathology 9(1): 9-16.

- Keeble E and Meredith A (2009). BSAVA Manual of Rodents and Ferrets, BSAVA, Gloucester.

- Meredith A and Johnson-Delaney C (2010). BSAVA Manual of Exotic Pets (5th edn), BSAVA, Gloucester.

- Thompson JJ et al (2016). Spontaneous splenic hemangiosarcoma in a guinea pig (Cavia porcellus), Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 25(2): 139-143.