30 Sept 2025

OA and flystrike in pet rabbits

Nichi Cockburn RVN, NCert(A&CC), CCRP, AdvCertVPhys, CCMP, MIRVAP(VP) and Richard Saunders BSc(Hons), BVSc, FRSB CBiol, DZooMed(Mammalian), DipECZM(ZHM), FHEA, FRCVS explain the correlation between two important issues, and the importance of spotting pain signs early.

Image: MJ iceberg / Adobe Stock

In the past few years, osteoarthritis (OA) has been increasingly appreciated as an enormous welfare issue for our pets; despite this, it is still underdiagnosed in many cases.

Statistics show more than 80% of dogs older than eight years have OA, and a study has demonstrated that 40% of dogs between the age of eight months old and four years have OA in at least one joint (Enomoto et al, 2024). Meanwhile, 90% of cats older than 12 years have radiographic evidence of OA, and 38% of all cats have clinical signs of OA.

In contrast, our knowledge and awareness of the incidence in rabbits is severely lacking. Rabbits are the third-most popular pet in the UK, but they still do not receive the attention they deserve when it comes to pain. This partly comes down to their prey species nature and ability to not show pain, but is even more so due to the fact that we simply do not observe them enough.

Dogs are typically walked daily, so any sign of “slowing down” for any reason is noticed relatively early on. Even cats move around the house, often up stairs; therefore, owners notice an absence of climbing, jumping up and other actions.

Suboptimal conditions

Rabbits are very often kept in severely suboptimal conditions such as hutches. Figure 1 shows a rabbit breeder’s hutch, stacked one on top of the other to further increase stocking density, as well as being extremely small.

But even hutches sold commercially for pet rabbits are nearly always far too small. These prevent them from exercising properly, with some hutches too small for a rabbit to even stand up on its back legs, a common behaviour in healthy rabbits (Figure 2).

This inability both contributes to, and hides, musculoskeletal disease. If an owner never sees their rabbit run, jump and binky, they simply cannot tell when the rabbit can no longer perform those actions (Figure 3).

OA in rabbits

Very few studies of OA in rabbits exist. A retrospective study of CT images of 311 rabbits found an incidence of 19.6%. Only 14.8% of the rabbits had clinical signs of OA recorded in the clinical notes (Bagha and Keeble, 2024).

OA is a complex condition that involves more than just the cartilage; it affects the joint capsule, synovial membrane, cartilage and subchondral bone. The joint dysfunction results in a cascade of events; it has a direct impact on the soft tissues such as the tendons and ligaments. The alterations in gait pattern and reduced mobility result in a loss of muscle mass and compensatory muscle pain, adaptations and myofascial pain.

Both mechanical and biological factors influence the progression of this degenerative disease, and several ways exist for us to impact this in practice.

The role of obesity in OA has been appreciated for a long time. However, we have traditionally focused on excessive weight contributing to a mechanical overload of the joint. This remains an important factor, but increasingly we are acknowledging the role of adipose tissue and adipokines. These are inflammatory mediators that contribute to the inflammatory process, cartilage degradation and joint destruction. Obesity in rabbits is common, and a lean body condition score is vital in OA management. Figure 4 shows a severely obese rabbit presented with flystrike, at least partly because it simply could not reach its back end to groom.

Reduced mobility is a key clinical sign of OA. The composition and function of synovial fluid is altered in OA, and it has many functions: it is required to bathe the joint, provide lubrication, supply key nutrients such as oxygen and remove waste products. The only way synovial fluid is replenished in the joint is via movement; no pump exists. Therefore, a rabbit that is sat in a hutch, or other small, confined area, does not have the ability to perform this vital task. Rabbits are a prey species and notoriously difficult to pain score – especially in practice. This is where we can utilise recent developments in feline medicine.

The focus in feline practice has shifted in recent years to focus on behaviours in the home, and client education is vital in improving the welfare of rabbits.

The use of clinical metrology instruments, such as the Feline Musculoskeletal Pain Index and client-specific outcome measures, has been a game changer in our awareness of pain – especially in cats that do not show the classic signs of joint pain, such as lameness. The concept is simple and easy for the clinical team and clients to implement. A number of activities are monitored, and change is noted and acted on.

A thorough history is especially important in recognising pain behaviours in rabbits. Client questionnaires could be completed in the waiting room or sent out before the consultation to gather vital information. It could even be sent out with vaccination reminders.

Classic signs of OA and pain in rabbits include:

- Slowing down.

- Sleeping more.

- Stiffness after rest.

- Change in gait pattern and hop sequence.

- Changes in posture at walk, stand and while toileting.

- Difficulty jumping up or down and reduced use of ramps.

- Appetite changes, including volume and food preference.

- Changes in behaviours such as grumpiness and aggression to humans or their house mates, or even withdrawn behaviours where they are much less interactive with the family.

- Licking the joints, or repetitive nibbling of an area.

- Pododermatitis.

- Excessive nail length from reduced activity such as digging.

- Inappropriate toileting, or not using the littler tray.

- Coat changes.

- Matted fur.

- Cheyletiella parasitovorax (“walking dandruff”) skin mite infestation.

- Urine staining.

- Inability to eat caecotrophs.

- Flystrike.

This list is neither exhaustive, nor is it certain that an individual rabbit will develop all of them, let alone in any particular order. However, as the condition worsens, and as the secondary effects of some signs interact (for example, a lack of exercise predisposes to obesity, and loss of muscle strength, itself further destabilising joints), a vicious circle develops which, sadly, often ends up in flystrike, which in a recent study was revealed to be the leading cause of euthanasia of rabbits presented to veterinary practices, and yet is wholly preventable (O’Neill et al, 2019).

Spondylosis

Spondylosis in rabbits is common. While the spondylosis is forming, it is painful, and once it is formed, it restricts movement of that particular area of the spine and puts stress on the areas cranial and caudal to its location. This can lead to the rabbit having an inability to groom and ingest their caecotrophs.

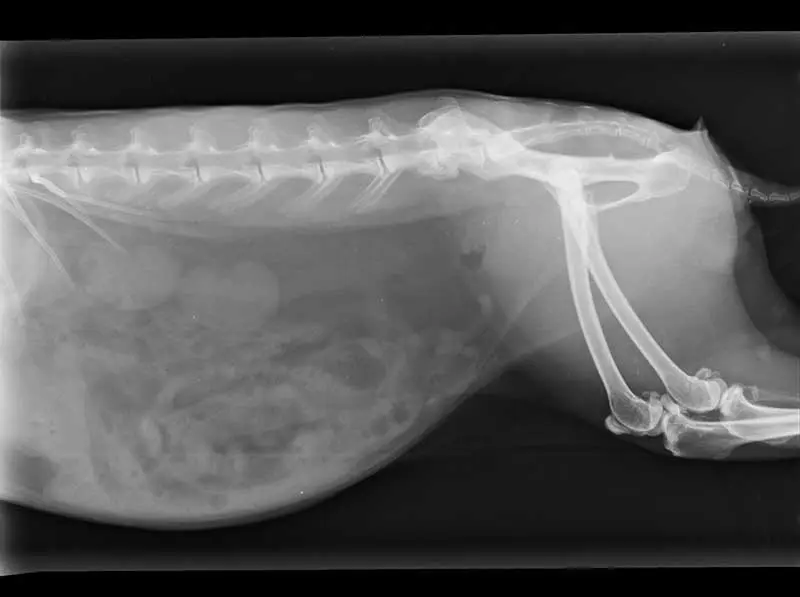

Figure 5 shows a rabbit with bridging spondylosis of the last two lumbar vertebrae.

Anecdotally, the authors have seen several cases where this pattern has been seen, and then, after a fall or a particularly over-enthusiastic run or jump, potentially after being chased or scared by a predator, the rabbit has been acutely much worse. The suspicion here is that the bridge of callus between those previously fused vertebrae has fractured or become unstable, leading to an acute on chronic source of additional, severe pain.

How many of the rabbits presented with gut stasis are in pain and, therefore, have not been as mobile, or not been able to eat as much as they need to maintain active gut motility?

How many rabbits that present with Cheyletiella species lesions between their scapulae are treated with acaricidal drugs, without exploring the mobility disorder that gives rise to them? Walking dandruff is, here, a red-flag warning of the development of more serious invertebrate attacks.

Flystrike

The question is, how many of the rabbits presented to us in practice with flystrike (Figure 6) have retained caecotrophs stuck around the rear end? (Figure 7).

These rabbits may also dribble urine (Figure 8) when passing it, and the mixture of these causes severe skin excoriation. They have both much more reason to need to groom, and yet have not been able to groom because of their joint pain and immobility.

Simple tricks such as home videos are a perfect tool to visualise a rabbit in its normal environment, alongside allowing it to move freely within the consult room, instead of examining on a table.

We need to be proactive in educating the veterinary team and rabbit owners about the clinical signs of pain in rabbits, and further research is needed to improve our diagnosis management of OA in rabbits; Figure 9 shows one of the authors performing laser therapy to assist such a patient.

- Article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 39, Pages 14-18.

References

- Bagha F and Keeble E (2024). Incidental osteoarthritis: risk factors, prevalence and clinical evidence in rabbits. UK-VET Companion Anim 29(2): 2-5.

- Enomoto M, de Castro N, Hash J et al (2024). Prevalence of radiographic appendicular osteoarthritis and associated clinical signs in young dogs, Sci Rep 14(1): 2,827.

- O’Neill DG, Craven HC, Brodbelt FC et al (2019). Morbidity and mortality of domestic rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) under primary veterinary care in England, Vet Rec 186(14): 451.