20 Nov 2017

Ovarian teratoma in a bearded dragon

Agata Witkowska details the case of a reptile with an abdominal mass, from its diagnosis to treatment and removal via surgery.

The bearded dragon.

This case study reports an ovarian teratoma in a female inland bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps). The article contains a detailed report of the diagnostic approach to the case, including a contrast radiograph that was performed. A detailed list of all medication, including references, is contained.

The article describes the surgical approach to the exploratory laparotomy in a bearded dragon and tumour removal with a successful outcome. The discussion focuses on the prevalence and reports of teratomas in the pet population. Several reports are available of different types of teratomas across different reptile species in the literature.

An adopted, three-year-old – presumed to be male – bearded dragon (Pogona vitticeps) was presented with a seven-day history of lethargy and lack of defecation.

The dragon appeared bright on presentation and was sexed as female during the clinical exam. It weighed 540g, with a body condition score of 3 out of 5. History revealed good husbandry, with appropriate environmental temperatures and an ultraviolet source.

During clinical exam, a big, irregular and painful abdominal mass was found, and impaction considered the most likely differential.

Case progression

The owner was keen on investigations into the abdominal mass and the dragon was admitted. Pain relief in the form of meloxicam at 0.3mg/kg (Rowland, 2009) and tramadol at 10mg/kg (Souza and Cox, 2011), and IM injections, were provided, and the animal seemed more comfortable.

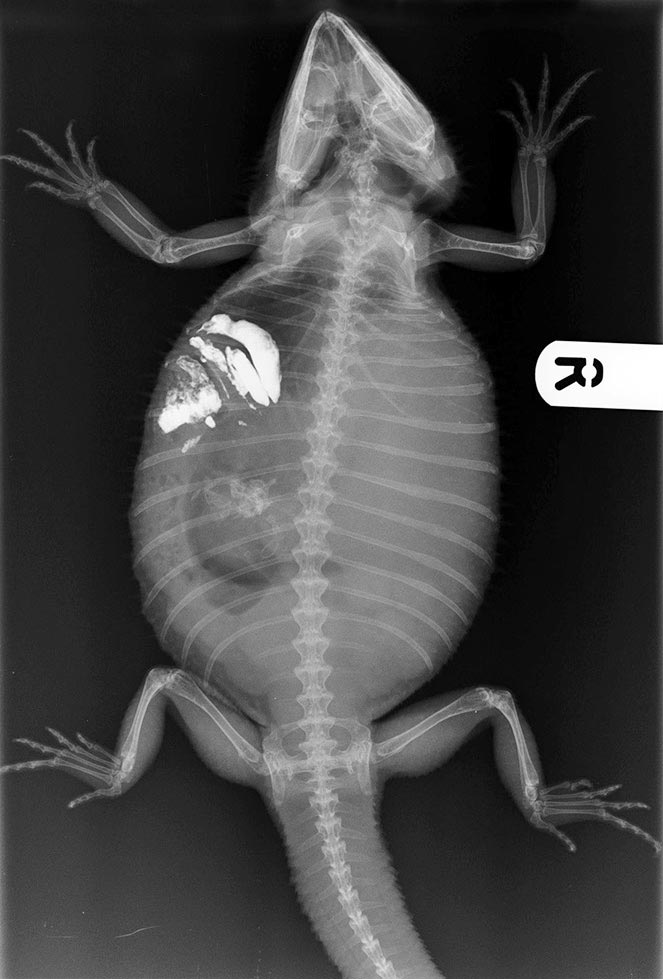

Conscious, dorsoventral radiographs of the dragon were obtained, which revealed a well-calcified skeleton, as well as a soft tissue mass in the abdomen. This did not help with further narrowing of the mass origin.

A further ultrasonographic examination of the abdomen was performed, which revealed part of the mass to be fluid-filled, with possible follicles present within the abdomen. Conservative treatment, and monitoring of appetite and behaviour, was elected at this stage.

Probiotic and electrolyte warm baths were started, and a faecal sample was obtained. This revealed a heavy infestation of nematodes and a product containing pyrantel was administered orally at 5mg/kg (Rowland, 2009).

Following defecation, the animal appeared brighter and the mass smaller. With permission of the owner, a barium sulfate solution was administered to further aid in determining the origin of the mass. An antibiotic injection, in the form of ceftiofur at 15mg/kg (Churgin et al, 2014), was also administered.

The following day, the dragon appeared not to have eaten overnight, but was still comfortable on abdominal palpation. Repeat radiographs were performed, revealing the barium solution was moving through the gastrointestinal tract properly and the mass was not connected to the tract, but was displacing it cranially (Figure 1).

At this point, an exploratory laparotomy was discussed with the owner, and a blood sample was collected from the ventral tail vein for a general health profile and to check the total calcium levels (Table 1). This was run in-house.

| Table 1. Patient’s biochemistry results | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Affected animal | Reference value |

| Aspartate aminotransferase U/L | 13 | 0-77 1 |

| Bile acids umol/L | <35 | |

| Creatinine kinase U/L | 247 | 59-7000 1 |

| Uric acid umol/L | 208 | |

| Glucose mmol/L | 13.9 | 7.72-16.2 2 |

| Calcium mmol/L | 3.61 | 2.2-6.8 2 |

| Phosphorus mmol/L | 1.49 | 1.1-3.2 2 |

| Total protein g/L | 46 | 36-64 1 |

| Albumin g/L | 23 | 13.46 1 |

| Globulin g/L | 23 | 10-44 1 |

| Potassium mmol/L | 4.4 | 1.0-6.5 2 |

| Sodium mmol/L | 140 | 141-190 2 |

| Reference ranges are provided where available. 1. Carpenter (2012). 2. Eliman (1997). |

||

Although the calcium levels were not raised above normal, a reproductive problem was the highest differential. An exploratory laparotomy was scheduled for the following day. The same painkillers were administered the following morning as part of a premedication protocol.

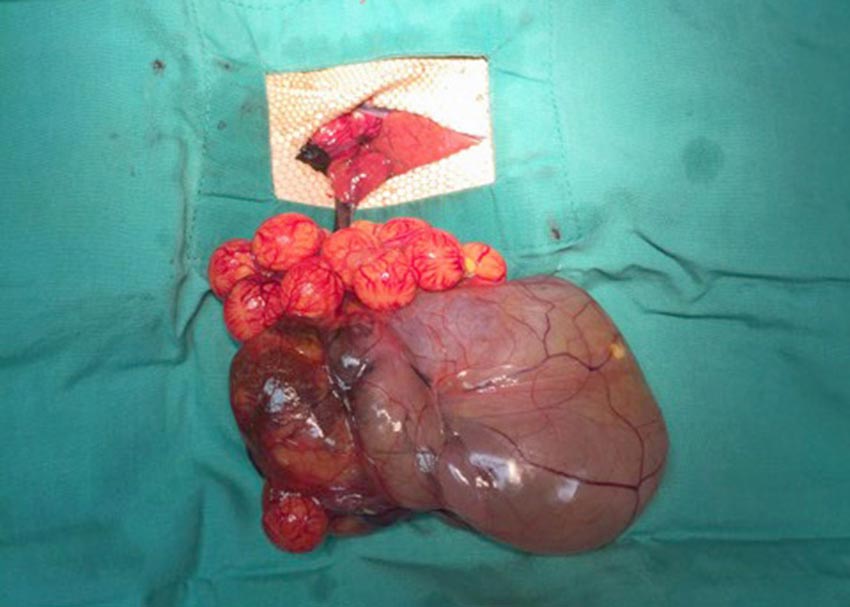

The reptile was anaesthetised using alfaxalone IV solution via the ventral tail vein at 5mg/kg (Rowland, 2009). The animal was intubated and placed in dorsal recumbency, and a ventilator was used to assist with intermittent positive-pressure ventilation. Inhalant anaesthesia, in the form of sevoflurane, was used along with oxygen. The surgical area was prepared with an iodine solution and a Doppler was used for heart rate monitoring. An off-midline, left abdominal incision was made and the mass gently exteriorised (Figure 2).

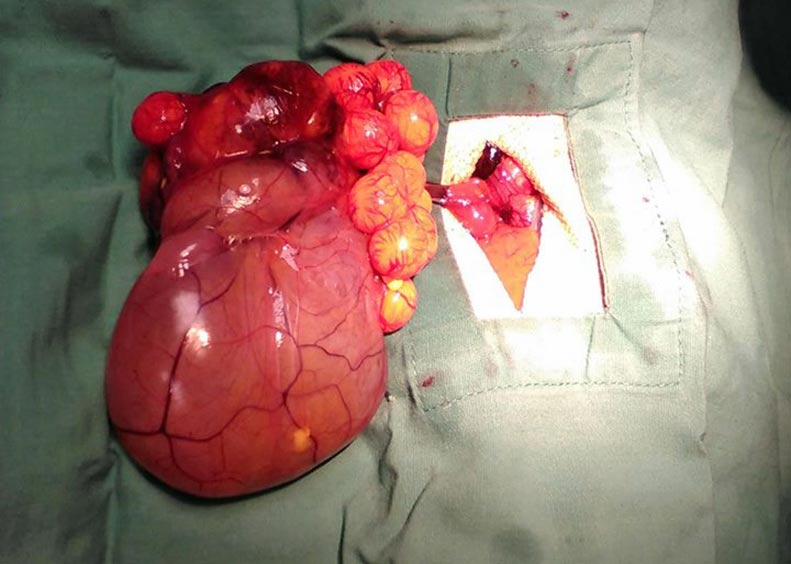

No obvious adhesions between the mass and other organs were noted, but normal follicles were present (Figure 3).

The ovarian pedicle was clamped and ligated with a single PDS-encircling ligature. Numerous follicles were noted in the right abdominal cavity and, as discussed with the owner prior to the surgery, the dragon underwent a bilateral ovariectomy. The abdominal cavity was flushed with sterile saline and inspected for any remaining follicles.

The skin was closed using a horizontal mattress suture, ensuring an everting pattern. Recovery from anaesthesia was uneventful.

Outcome

The following day, the reptile appeared bright and free of pain – and showed interest in food, eating numerous insects. It was discharged with an oral NSAIDs suspension and a postoperative check-up appointment was booked for seven days after, with a final suture removal in six weeks.

Mass monitoring

Following the mass removal, the nurse continued to monitor it for 30 minutes.

A soft tissue, fluid-filled component was wrapped around half of the mass (later confirmed as part of a gastrointestinal tract) and seemed to show peristalsis-like movements. Another, smaller, blood-filled component present on the opposite side of the tumour appeared to have numerous blood vessels leaving it and continued to contract for 30 minutes post-removal. The main, hard component of the mass was incised into, revealing cartilage, bones and reptile skin inside. With the owner’s consent, the mass was sent for histopathological examination, which confirmed an ovarian teratoma, as suspected.

Case discussion

A teratoma is defined as a tumour composed of a mixture of tissues different to that it originates from (Willis, 1951). Teratomas have been described in many veterinary species, with most reports among mammals.

Ovarian neoplasias in cats and dogs are reported as rare. They can often be asymptomatic, and an incidental finding during routine surgeries with a medium age of onset (Cote, 2014). In humans, the size of ovarian teratomas appears to be age related, with bigger and more symptomatic tumours found in younger patients (Kim et al, 2011).

The potential for malignancy of an ovarian neoplasia depends on its level of differentiation, with less developed tumours, such as embryonal carcinomas, exhibiting more malignancy than teratomas (Patnaik and Greenlee, 1987).

Teratomas are not exclusive to a single sex or the reproductive tract, and reports of their occurrence in other tissues, such as the cranium, exist (Reindel et al, 1996).

The gross appearance of this patient’s tumour, with no obvious abdominal adhesions, lack of radiographic evidence of metastasis and histopathological report, would warrant a low potential of metastasis.

It is surprising how such a big mass, with a very well-developed blood supply, originated from such a small ovarian pedicle. It is unknown whether the animal was exposed to males of its species or used for breeding prior to change of ownership. Prior to the sudden onset of lethargy and inappetence, the animal exhibited no sign of being unwell, and it is, therefore, difficult to estimate the timeline of the tumour development.

Several reports of ovarian teratomas in reptiles exist, ranging from benign tumours in a red-eared slider (Hidalgo-Vila et al, 2006) to malignant in the same species (Newman et al, 2003).

Hidalgo-Vila et al (2006) found elevated calcium levels in their patient, which are often present in gravid, female reptiles, but were lacking in this patient. This is an interesting variation in this case, as the reptile was found to be gravid and, subsequently, spayed during the exploratory laparotomy. A normal, total blood calcium level should, therefore, not exclude a reproductive problem.

Ovarian teratomas have been well described in the green iguana (Wenger et al, 2010), with a good surgical outcome. Most reported clinical symptoms are those expected to be caused by an abdominal space-occupying lesion, such as respiratory or digestive disturbance (Reavill and Schmidt, 2007).

Conclusion

Ovarian neoplasias are rare in veterinary species and suspected to be often underdiagnosed in less familiar species, such as reptiles.

Our lack of understanding of pain expression in reptiles makes it difficult to spot disease early for many owners and many reptiles are often presented to the clinician in late stages of disease.