28 May 2018

Paget’s disease in a Brazilian rainbow boa

A Case Notes article from Sonya Miles takes the less-usual case of a three-year-old male, captive bred Brazilian rainbow boa.

Image © sipa / Pixabay

A three-year-old male, captive bred, Brazilian rainbow boa (Epicrates cenchria cenchria) was referred to Highcroft Veterinary Referrals with a five-month history of anorexia, lethargy and the inability to move, hold itself up properly or to right itself.

When taking a clinical history, it became evident the snake was inappropriately looked after. It was not provided with any heat or the correct humidity. The substrate was not suitable and it had limited opportunity for arboreal activity. The snake had historically suffered multiple respiratory tract infections – one of which had previously led to a bout of suspected septicaemia. No investigations were performed at the time and the snake was only provided with antibiotics (five injections of 20mg/kg ceftazidime IM). The owners reported the snake recovered well, but, on reflection, may never have returned to normal.

Examination

On a clinical examination, the snake was of adequate body condition, weighing 0.91kg. Oral examination was within normal limits and it had no signs of an upper respiratory tract infection at the time. The snake had multiple areas of retained shed, including multiple layers of retained spectacles bilaterally. The heart was assessed using Doppler and its rate and rhythm were within normal limits, as was the snake’s respiratory rate and effort. Coelomic palpation was normal, but the snake resented spinal palpation. Multiple raised, hard areas were palpable when feeling the spine. When placed on a flat surface the snake was unable to move the middle and caudal thirds of its body. When placed in dorsal recumbency the snake was unable to right itself.

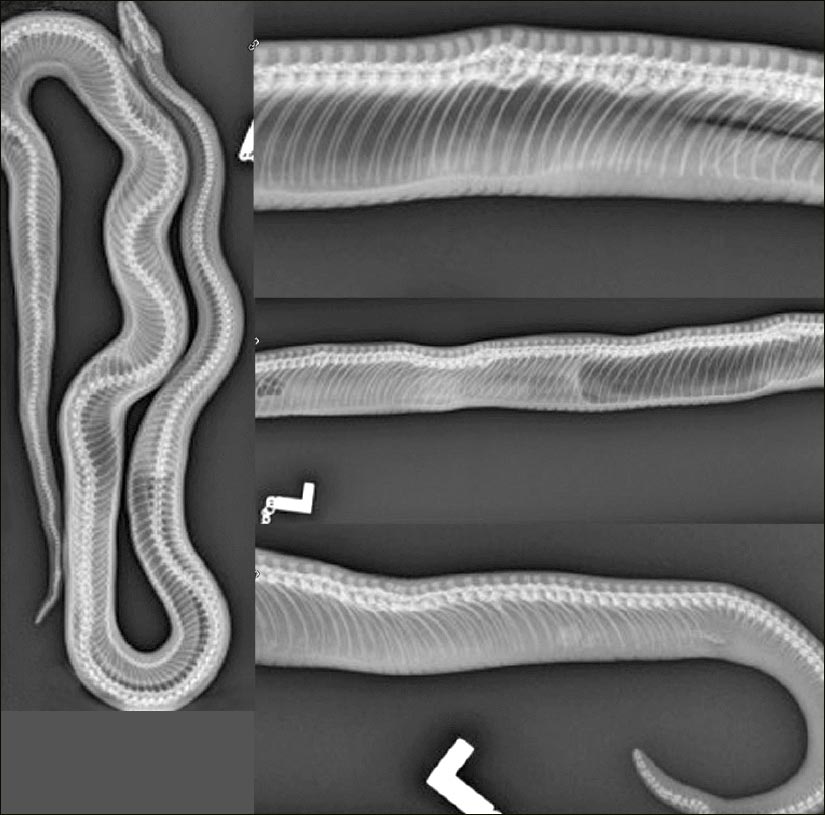

After the snake was admitted, 10mg/kg of alfaxalone was given IV to sedate it and 2ml of blood taken directly from the heart. Plain radiographs were then performed – both dorsoventral and multiple lateral views along its length (Figure 1). On the radiographs it was evident multifocal proliferative changes to many of the vertebral bodies existed, causing severe spinal cord compression in many cases. Osteitis deformans, also known as Paget’s disease, was the most likely differential.

To investigate the disease process and to confirm diagnosis, biopsies of the areas of concern were recommended; however, in this case, due to the fact the snake had not eaten for months, had lost its righting reflex and inability to move its body from the middle third caudally, or support its own weight, the owner elected to euthanise the reptile. In light of this decision, the owner decided not to send the bloods for analysis.

Osteitis deformans is a chronic remodelling disorder of bone that often results in the increase of new bone at various sites along the spine – the most common site in snakes. Many potentially aetiological agents can result in these changes, which are under intensive investigation. These involve genetic factors, chronic bacterial and viral infections, as well as metabolic bone disease. In this case, the underlying aetiological agent was not discovered.