3 Oct 2016

Treating and maintaining exotic squirrels as companion animals

Marie Kubiak discusses caring for some uncommon members of the squirrel family kept as pets in the UK, including Siberian chipmunks and Richardson’s ground squirrels.

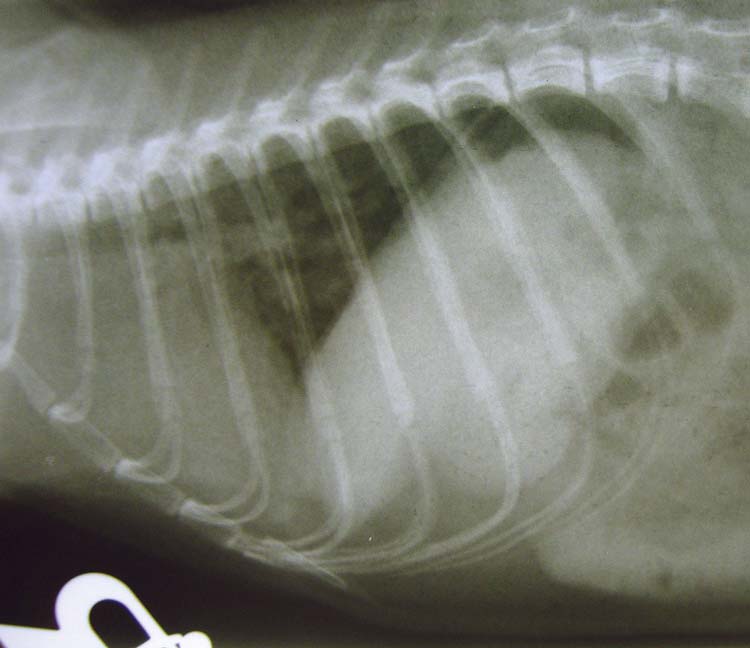

Figure 1. A large cranial abdominal mass was noticed by the owner. Ultrasound confirmed the liver as the organ of origin and surgical excision was scheduled.

Members of the squirrel family are uncommon pets in the UK, but, of this group, Siberian chipmunks, black-tailed prairie dogs and Richardson’s ground squirrels appear to be the most commonly kept as companion animals.

Many disease syndromes are common to all three species, including acquired dental disease, elodontoma, bacterial pneumonia and neoplasia.

Siberian chipmunks originate from northern Asia and are a small species, measuring 18cm to 25cm in length, including the tail. Their lifespan is 5 to 10 years in captivity.

They are omnivores, feeding predominantly on seeds, grains and fruits, but will opportunistically take small vertebrates and invertebrates. They are active and do not tolerate handling well; large arboreal enclosures with plenty of hiding places are ideal.

Although previously a common pet in the UK, in 2016, the Siberian chipmunk was added to a European Union list of invasive alien species, meaning it can no longer be bred and sold by private owners and pet shops have a two-year period to deplete their stocks. Ultimately, this will result in an absence of the species being kept as pets.

Prairie dogs (Cynomys species) are North American members of the squirrel family and have five recognised species. Of these, only the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) is encountered with any frequency as a pet in this country. They feed on grasses, seeds, leaves and roots, with occasional opportunistic feeding on insects. They are large for sciuromorpha and can weigh up to 2kg.

Well-socialised individuals can make good pets, but even the most tame prairie dog can become aggressive during its breeding season. Captive animals require deep substrate to form their burrows.

Richardson’s ground squirrels (RGS; Urocitellus richardsonii) are native to the grasslands of the northern US and southern Canada, and do cross over territory with prairie dogs. Their diet is omnivorous, with adults feeding on vegetation, insects and seeds, and they are seen as pests in farming areas.

RGS are infrequently kept exotic pets in the UK. In captivity they can be maintained in social colonies and, though destructive, tend to make good companion animals with regular handling and interaction.

Neutering

These species can often be maintained as single-sex groups, although prairie dogs, in particular, can become aggressive to conspecifics and handlers during their breeding season (“the rut”), necessitating separation.

Where animals are being kept as a mixed-sex group, then neutering of males is the simplest way to control breeding. Open inguinal canals in these species necessitate a closed castration technique and the author prefers a midline abdominal approach with retraction of testes into the abdomen prior to ligation and removal.

This results in a single incision, compared with two scrotal incisions, and has reduced potential for postoperative infection, as scrotal wounds tend to be heavily contaminated due to ventral and perianal position. Wound closure is routine, with intradermal skin sutures to minimise wound interference.

Females can be spayed following a similar approach to other small mammals.

Elective surgery is best carried out in animals of less than one year old, and in summer time, where they are at their lowest bodyweight. In older animals, or at winter weight, large adipose deposits make surgery more challenging.

Neoplasia

Neoplasia appears uncommon in chipmunks. Two osteosarcomas have been described as having a mammary adenocarcinoma and a single report of hepatic carcinoma (Oohashi et al, 2009; Morera, 2004; Tamaizumi et al, 2007; Wadsworth et al, 1982).

Spontaneous neoplasia has been reported as uncommon in RGS, with limited case reports comprising a mast cell tumour and several adenocarcinomas (He et al, 2009; Yamate et al, 2007; Carminato et al, 2012).

A hepadnavirus-induced syndrome of hepatitis progressing to hepatic carcinoma has been recognised in RGS (Tennant et al, 1991) as well as woodchucks (Marmota monax), Californian ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi) and Arctic squirrels (Spermophilus parryii; Testut et al, 1996). The hepadnaviruses appear to be highly host-specific with no cross-infection between squirrel species.

A high prevalence of hepatic carcinomas has been reported in prairie dogs, presumed to be associated with hepadnavirus, but testing has not confirmed hepadnaviral presence (Garner et al, 2004). Otherwise, neoplasia in prairie dogs appears uncommon with sparse case reports comprising lymphoma, lipoma and osteosarcoma (Miwa et al, 2006; Mouser et al, 2006; Rogers and Chrisp, 1998).

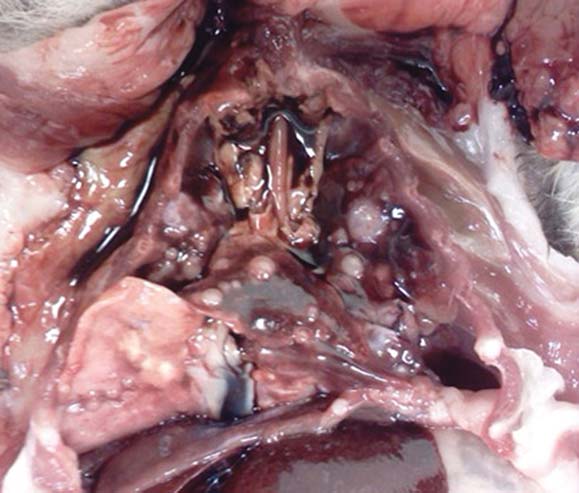

The author has seen a high incidence of spontaneous soft tissue and hepatic neoplasia in UK RGS, with females predominantly affected (Figures 1 and 2), but has yet to see a case of neoplasia in a prairie dog, suggesting viral presence is not ubiquitous and neoplasia is unusual in UK prairie dogs.

Dental disease

Sciuromorpha have a typical sciuromorpha dental formula of I – 1/1, C – 0/0, P – 1-2/1, M – 3/3, with continuously growing aradicular elodont incisors, whereas the premolars and molars have closed anelodont roots and do not have a pattern of ongoing growth and attrition (Legendre, 2003; Kertesz, 1993).

Acquired dental disease leading to incisor malocclusion has been described as common in chipmunks and is also regularly seen in other sciuromorpha (Girling, 2002). Incisor extraction is preferred over repeat incisor trims due to the stress to the patient and progression of dental changes over time. It is prudent to radiograph those animals presenting with incisor malocclusion, as elodontoma presence may be the cause of the coronal alteration.

Dental caries, periodontal disease and tooth decay can develop in animals on a high sugar diet (Mancinelli and Capello, 2016) and often extraction is the only option remaining due to advanced disease at the time of presentation.

Elodontomas

Elodontomas are a benign, but progressive, accumulation of alveolar bone and odontogenic material at the apices of elodont teeth.

As squirrels have elodont incisors, but closed-rooted premolars and molars, this dysplasia can only affect incisor apices. The resulting space-occupying mass is painful and, when upper incisors are involved, can obstruct nasal airflow. Elodontomas have been reported in sciuromorpha in the literature in both prairie dogs and chipmunks, and the author has also confirmed the presence of elodontomas in several RGS using radiography and CT imaging (Figure 3).

Possible inciting factors include trauma, chronic inflammation, advanced acquired dental disease and toxin exposure.

Treatment options attempt to alleviate the secondary respiratory consequences and include extraction of incisors and elodontoma, or trephination of the nasal sinuses to allow air flow through an alternative route (Smith et al, 2013; Bulliot and Mentre, 2013).

Surgery is more challenging in squirrels and chipmunks compared to prairie dogs, given the smaller patient size and disproportionally narrower nasal passages.

Pneumonia

Although respiratory distress is commonly associated with elodontoma presence, lower respiratory tract infections are also seen as a cause of dyspnoea. Primary pathogens have been implicated, such as Pasteurella multocida in prairie dogs.

However, in many cases, especially in chipmunks, husbandry failings leading to stress and immunosuppression are thought to be the primary inciting factor for development of opportunistic bacterial pneumonia.

Ideally, therapy would be based on a firm diagnosis made from radiography, and culture and cytology of a tracheal or bronchoalveolar lavage sample (Figure 4). In many cases this is not possible due to patient status or client funds and broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, with or without nebulisation, is a compromise.

Metastatic hepatic carcinoma can cause severe pulmonary changes with dyspnoea that is non-responsive to supportive or attempted treatment (Figure 5).

Arthritides

Stifle swelling, new bone formation and altered range of movement have been seen by the author in several geriatric RGS and less commonly in prairie dogs (Figures 6 and 7).

Management using meloxicam and glucosamine/chondroitin appeared to assist with mobility, alongside husbandry modification to house affected animals in a single-tier cage. In one case, acupuncture resulted in a perceived marked improvement by the owner. A single case of mycobacterial synovitis has also been seen, but no other infectious joint conditions.

Traumatic injury

In rut, male prairie dogs may compete for territory, inflicting bite wounds on other animals – typically affecting the tail base, scrotum and dorsum. Most wounds are relatively superficial, but may require suturing.

More severe trauma has been seen following a fall from a cage tier, or a drop from an owner’s hands. Limb and spinal fractures have both been seen by the author, and intervertebral disc rupture has been seen in a geriatric prairie dog following a fall (Figure 8).

Conclusion

Squirrel species may be unfamiliar to many practitioners, but the majority of clinical syndromes noted are uniform across this family and may be seen in more familiar species.

References

- Bulliot C and Mentre V (2013). Original rhinostomy technique for the treatment of pseudo-odontoma in a prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 22(1): 76-81.

- Carminato A, Nassuato C, Vascellari M, Bozzato E and Mutinelli F (2012). Adenocarcinoma of the dorsal glands in 2 European ground squirrels (Spermophilus citellus), Comparative Medicine 62(4): 279-281.

- Garner MM, Raymond JT, Toshkov I and Tennant BC (2004). Hepatocellular carcinoma in black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludivicianus): tumor morphology and immunohistochemistry for hepadnavirus core and surface antigens, Veterinary Pathology 41(4): 353-361.

- Girling S (2002). Mammalian anatomy and Imaging. In Meredith A and Redrobe S (eds), BSAVA Manual of Exotic Pet Medicine, BSAVA, Gloucester.

- He XJ, Uchida K, Tochitani T, Uetsuka K, Miwa Y and Nakayama H (2009). Spontaneous cutaneous mast cell tumor with lymph node metastasis in a Richardson’s ground squirrel (Spermophilus richardsonii), Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 21(1): 156-159.

- Kertesz P (1993). A Colour Atlas of Veterinary Dentistry and Oral Surgery, Wolfe Publishing, London.

- Legendre LF (2003). Oral disorders of exotic rodents, Veterinary Clinics of North America: Exotic Animal Practice 6(3): 601-628.

- Mancinelli E and Capello V (2016). Anatomy and disorders of the oral cavity of rat-like and squirrel-like rodents, Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 19(3): 871-900.

- Miwa Y, Matsunaga S, Nakayama H, Kurosawa A, Ogawa H and Sasaki N (2006). Spontaneous lymphoma in a prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association 42(2): 151-153.

- Morera N (2004). Osteosarcoma in a Siberian chipmunk, Exotic DVM 6(1): 11-12.

- Mouser P, Cole A and Lin TL (2006). Maxillary osteosarcoma in a prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 18(3): 310-312.

- Oohashi E, Kangawa A and Kobayashi Y (2009). Mammary adenocarcinoma in a chipmunk (Tamias sibiricus), Journal of Veterinary Medical Science 71(5): 677-679.

- Rogers K and Chrisp C (1998). Lipoma in the mediastinum of a prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science 37(1): 74-76.

- Smith M, Dodd JR, Hobson H, and Hoppes S (2013). Clinical techniques: surgical removal of elodontomas in the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) and the eastern fox squirrel (Sciurus niger), Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 22(3): 258-264.

- Tamaizumi H, Kondo H, Shibuya H, Onuma M and Sato T (2007). Tail root osteosarcoma in a chipmunk (Tamias sibiricus), Veterinary Pathology 44(3): 392-394.

- Tennant BC, Mrosovsky N, McLean K, Cote PJ, Korba BE, Engle RE, Gerin JL, Wright J, Michener GR, Uhl E and King JM (1991). Hepatocellular carcinoma in Richardson’s ground squirrels (Spermophilus richardsonii): evidence for association with hepatitis B-like virus infection, Hepatology 13(6): 1,215-1,221.

- Testut P, Renard CA, Terradillos O, Vitvitski-Trepo L, Tekaia F, Degott C, Blake J, Boyer B and Buendia MA (1996). A new hepadnavirus endemic in arctic ground squirrels in Alaska, Journal of Virology 70(7): 4,210-4,219.

- Wadsworth PF, Jones DM and Pugsley SL (1982). Primary hepatic neoplasia in some captive wild mammals, Journal of Zoo Animal Medicine 13(1): 29-32.

- Yamate J, Yamamoto E, Nabe M, Kuwamura M, Fujita D and Sasai H (2007). Spontaneous adenocarcinoma immunoreactive to cyclooxygenase-2 and transforming growth factor-beta1 in the buccal salivary gland of a Richardson’s ground squirrel (Spermophilus richardsonii), Experimental Animals 56(5): 379-384.