10 Jun 2025

Adhesive gel barrier use for management of orf in lambs

Emily Farrow BVetMed, CertAVP, MRCVS looks at a case series following the use of this treatment for contagious pustular dermatitis, a virus transmitted through contact with damaged or scarified skin.

Image © travelwitness / Adobe Stock

Contagious pustular dermatitis (orf, scabby mouth, contagious ecthyma and sore mouth) is a skin disease caused by a parapoxvirus. The disease mainly affects sheep and goats, typically causing a debilitating pustular dermatitis around the mouth, lips and nose of youngstock, and on the teats of dams. This, in turn, increases the risk of mastitis.

Orf is also zoonotic, with people whose occupation brings them into contact with infected animals (for example, farmers and veterinarians) at greatest risk of infection.

Although morbidity is high, with levels of up to 100% reported (Higgs et al, 1996), orf infections are usually self limiting, with mortality less than 1% (Small et al, 2019). However, where complicating secondary factors such as stress, immunosuppression or concurrent disease are present, mortality can increase to 50% (Scagliarini et al, 2012).

The disease has significant financial importance to the UK sheep industry, estimated in 2003 to have cost the British economy £10 million a year (AHDB Beef and Lamb, 2005). The prevalence of orf in the English flock has been estimated at 2% in ewes and 20% in lambs (Onyango et al, 2014). Based upon Defra’s Livestock population report, in June 2024, England had a breeding ewe population of 6.6 million and 6.9 million lambs below one year (Defra, 2024); this translates to roughly 132,000 ewes and 1.4 million lambs infected per year in England alone.

This case series follows a trial of an adhesive gel barrier for the management of orf in lambs. The remainder of this article shall focus solely on orf in lambs; however, the author notes that this product could be, and has been, used in alternative orf presentations, with variations in the area affected and/or age of animal.

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

In lambs, following roughly one week’s incubation period, viral replication of the parapoxvirus leads to oedematous and granulomatous inflammation of dermal cells (Spyroua and Valiakos, 2015). This inflammation causes erythematous spots that progress to vesicles, papules and suppurative pustules on the mouth, lips and nose (Spyroua and Valiakos, 2015), which may progress into the buccal cavity, affecting the young animals’ ability to suckle.

The suppurative lesions progress to scabs, which become dry and are then shed, leaving healed skin underneath. These scabs deposit the virus into the environment and remain an infection risk to other stock (Haig and McInnes, 2002).

Primary infections can be severe, taking six to eight weeks to resolve (Haig and McInnes, 2002). If an animal becomes reinfected, lesions tend to resolve more rapidly, usually within three weeks (Haig and McInnes, 2002).

The characteristic clinical signs and lesions of orf are often enough to make a presumptive diagnosis. The author notes that notifiable diseases such as foot-and-mouth disease and bluetongue also present with vesicles around the mouth. If in doubt, any suspicion of these notifiable diseases should, of course, be reported to Defra.

Treatment and prevention

The orf virus is transmitted through contact with damaged or scarified skin. It is incredibly resilient, surviving in the environment for up to 17 years and offering infection risk from one lambing season to the next if not appropriately disinfected with anti-viral agents (Spyroua and Valiakos, 2015).

Biocontainment, therefore, plays an essential role in control of orf in infected flocks. Animals showing clinical signs of disease should be isolated to prevent the spread of disease to uninfected animals. Due to the zoonotic risk, gloves should be worn when handling infected animals. In the UK, a licensed live attenuated orf vaccine exists that can be used to vaccinate adult and neonatal animals on endemically infected farms. When used correctly, vaccination offers effective control of orf. However, Small et al (2019) highlighted issues with compliance of the vaccination guidelines, which may impact vaccine efficacy on UK sheep farms.

Many anecdotal methods are used to manage orf. Most involve trying to prevent or treat the secondary bacterial infections, and both systemic and topical antibiotics are often utilised. However, unless secondary bacterial infection is confirmed, the use of topical or systemic antibiotics is hard to justify in the treatment of this viral disease. In addition, topical antibiotics in aerosol form are difficult to apply precisely to lesions – especially when located near the eyes.

The difficulties in getting vaccination implemented correctly, in addition to ongoing efforts to reduce antibiotic use in production animals, demonstrate a definite gap in the market for an effective, user-friendly product to help manage orf infections.

Case series

Derwent Vale Farm Vets in Pickering, North Yorkshire, recruited five affected farms to trial an adhesive gel barrier for its effectiveness to help manage orf lesions.

Scabs in the early stages of the disease should not be removed, as this can delay healing and increase trauma to the affected tissues. Also, unless all scabs are carefully collected and discarded, their presence in the environment will increase infection risk to the rest of the flock.

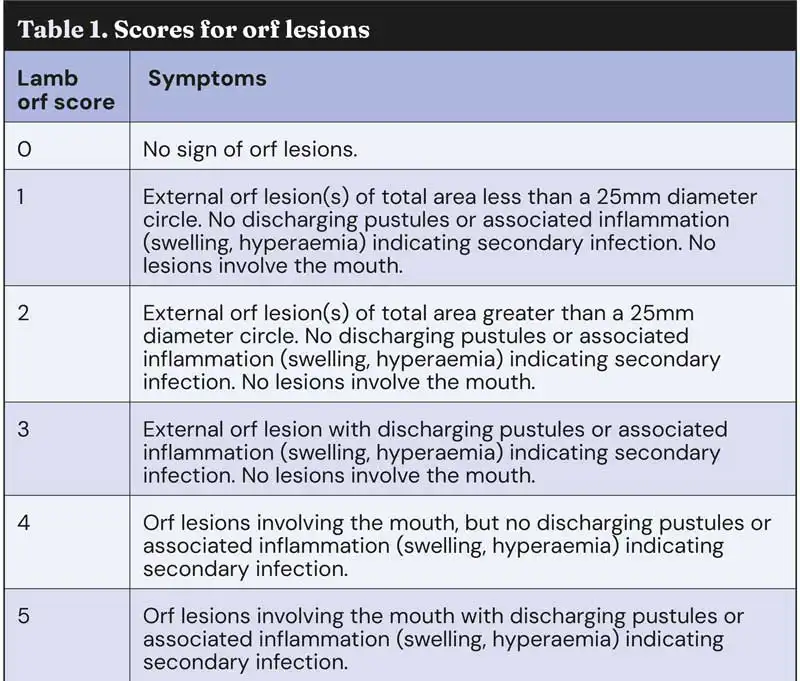

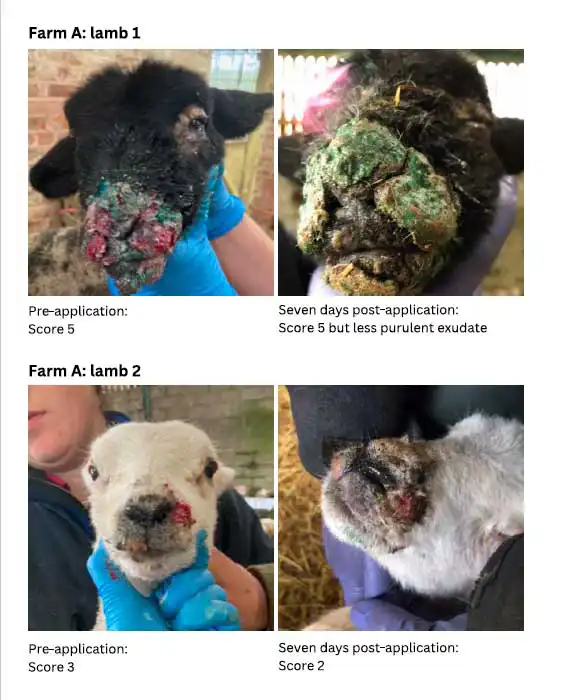

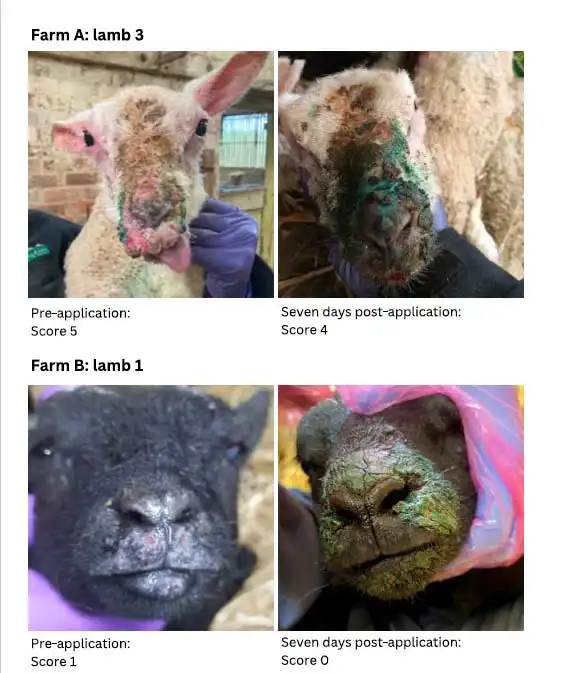

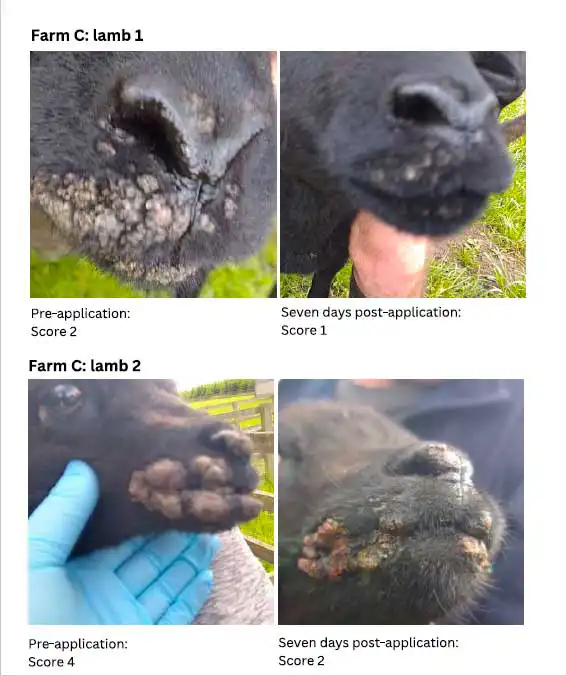

On the first visit, a veterinarian examined the lambs (approximately one month old) to confirm infection. The lesions were graded (Table 1) and photographed.

Wearing gloves, a layer of adhesive gel barrier was applied over the lesions.

The product was applied once on day one by a vet, then was left for the farmers to apply to new cases or to repeat application to lesions that still had discharge on day two.

A follow-up visit to photograph and record lesion progression occurred seven days later. The majority of lambs only had one layer of product applied.

On both visits, lesions were graded using the scoring system in Table 1 (Lovatt et al, 2012).

Results

Farm A

Farm A purchased more than 250 pet lambs. A high level of severe orf lesions were reported. Most had some discharge at the first visit.

Product application resulted in drier lesions. At the follow-up visit seven days later, most lesions had a significant reduction in suppurative exudate, which had dried to form a thick crust covering each lesion.

Farm B

At Farm B, mild lesions in a pedigree blue Texel lamb were reported. A resolution of the symptoms were recorded by second visit.

Farm C

Mild lesions in pedigree Hebridean lambs were reported at Farm C. Substantial improvement in lesions grades were recorded at seven days.

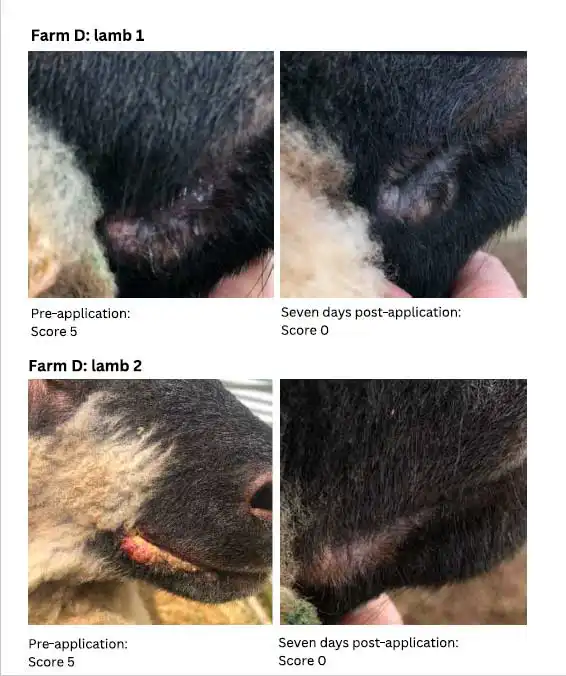

Farm D

Pedigree sheep and lambs from Farm D were headed for a Yorkshire show. The product was applied once to most, a second time to those that required it, and all healed within two weeks (in time for show day).

Farm E

Farm E purchased a small amount of pet lambs. Mild lesions were reported on farm. Most lesions were drier with crust formation one week later.

Economic analysis in lambs

It has been shown that, on average, orf-infected lambs are 2.2kg lighter at the end of an orf outbreak compared to uninfected lambs, and it has been assumed this remains up to weaning (Lovatt et al, 2012). This allows predictions of cost of the disease for lambs to be calculated:

Lowland lambs affected by orf take approximately two extra weeks to finish and consume 1kg concentrate per day (Stubbings, 2007).

Orf lambs reared on a less-favoured area (LFA) farm are comparable to 32kg stores which finish in 12 weeks by gaining 0.7kg a week off grass with 1kg of concentrate a week (AHDB Beef and Lamb, 2005).

By comparison, unaffected LFA lambs are equivalent to 34kg stores that can finish in six weeks by gaining 1kg a week off grass, with 1kg of concentrate a week (AHDB Beef and Lamb, 2005).

Concentrate cost is estimated at £305 per tonne (AHDB, 2025)

Therefore, affected lambs consume 6kg more concentrate in an LFA and 14kg more concentrate in a lowland situation. Additional feed costs alone are, therefore, estimated at £1.83 to £4.27 per orf-affected lamb.

When considering treatment costs, present management mainly involves every orf-affected lamb receiving treatment with a topical antibiotic spray to try to prevent secondary infections. Around 10% of orf-affected lambs also receive an antibiotic injection to treat secondary infection (Lovatt et al, 2012).

As the author writes, the estimated costs of these treatments are £0.40 per topical antibiotic spray and £0.75 per antibiotic injection (not accounting for any use of anti-inflammatory treatments).

It has been shown that mortality in orf-affected lambs increases by 3% (Lovatt et al, 2012). Mortality rates are likely to be higher in affected flocks due to the lambs having to remain on farm for an extended period.

Overall, endemic orf has a direct impact on costs such as veterinary time and treatments. Additional indirect costs include varying lamb prices, as farms risk missing peak lamb sale prices due to increased time on farm to reach weight. Orf will also increase labour costs, as dealing with cases is time consuming and endemic infections can be detrimental to farm staff morale.

Discussion

Orf is a nasty virus that is known to have significant negative effects on lamb productivity and welfare. The symptoms are also inherently difficult to manage once the virus is established. Although there are various remedies that claim to be the solution, orf lesions remain encumbering and frustrating for farmers in addition to being painful and distressing for the lambs.

During this small on-farm trial, after application of the adhesive gel barrier to orf lesions, Ambugreen (NoBACZ Healthcare) proved to be beneficial to the resolution of all lesions in varying degrees. Healing was noted as being “quicker than expected”, in the mild cases.

In the severe cases (as seen on Farm A), great improvements were still evident; the lesions appeared drier with less or no infection after seven days, although they may have required a second application on day two.

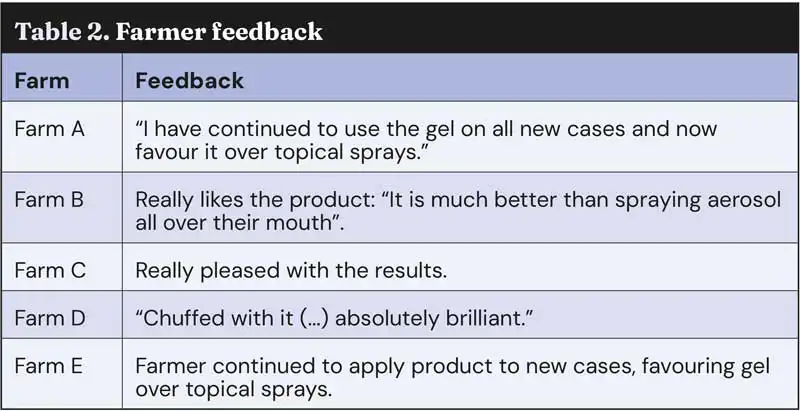

All five farmers provided positive feedback (Table 2). The author also found the gel a very easy product to apply topically to the face, and less distressing for the lambs than aerosol sprays.

Although it was beyond the scope of this case series, the author believes it would be beneficial to carry out further work to understand if the use of a barrier gel could reduce the spread of orf within the flock and potentially decrease disease transmission within the flock.

Conclusion

The use of a gel barrier over orf lesions seems to provide an environment that allows the skin to heal, which in turn could decrease the chance of secondary bacterial infections. Further research is necessary, but the use of an adhesive gel barrier could result in a reduction in:

- severity of the lesions

- impact on growth rate

- volume of antibiotics used on farm

- number of infectious scabs in the environment

- transmission rate within the flock

- transmission to humans

Acknowledgments

The case series was supported by NoBACZ Healthcare, but it did not participate in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data. The authors have no conflicts of interest. Many thanks to the clients of Derwent Vale Farm Vets who participated in the product trial.

- Use of some of the drugs in this article is under the veterinary medicine cascade.

- This article appeared in Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 23, Pages 17-19.

- This article was updated at the request of the author on 18 July 2025 to update wording in the farm case images and some of the text.

References

- AHDB Beef and Lamb (2005). Growing and finishing lambs for Better Returns, information available via https://ahdb.org.uk/knowledge-library/growing-and-finishing-lambs-for-better-returns

- AHDB Beef and Lamb (2025). Feed prices and markets, visit https://ahdb.org.uk/dairy/feed-prices-and-markets Defra (2024). Livestock populations in England at 1 June 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/livestock-populations-in-england/livestock-populations-in-england-at-1-june-2023

- Haig DM and McInnes CJ (2002). Immunity and counter-immunity during infection with the parapoxvirus orf virus, Virus Research 88(1-2): 3-16.

- Higgs A, Norris R, Baldock F, Campbell N, Koh S and Richards R (1996). Contagious ecthyma in the live sheep export industry, Australian Veterinary Journal 74(3): 215-220.

- Lovatt FM, Barker WJW, Brown D and Spooner RK (2012). Case-control study of orf in preweaned lambs and an assessment of the financial impact of the disease, Veterinary Record 170(26): 673.

- Onyango J, Mata F, McCormick W and Chapman S (2014). Prevalence, risk factors and vaccination efficacy of contagious ovine ecthyma (orf) in England, Veterinary Record 175(13): 326.

- Scagliarini A, Piovesana S, Turrini F, Savini F, Sithole F and McCrindle CM (2012). Orf in South Africa: endemic but neglected, Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 79(1): E1-E8.

- Small S, Cresswell L, Lovatt F, Gummery E, Onyango J, McQuilkin C and Wapenaar W (2019). Do UK sheep farmers use orf vaccine correctly and could their vaccination strategy affect vaccine efficacy?, Veterinary Record 185(10): 305.

- Spyrou V and Valiakos G (2015). Orf virus infection in sheep or goats, Veterinary Microbiology 181(1-2): 178-182.

- Stubbings L (2007). The prevalence and cost of sheep scab, Proceedings of the Sheep Veterinary Society 31: 113–115.