19 Feb 2018

Age at first calving: impact on future of dairy herd

Virginia Sherwin discusses how this can affect heifer rearing and be optimised for best performance efficiency and production.

The future of a dairy herd is the incoming replacement heifers, with the aim of introducing new genetic potential and improving performance of the herd. The industry target for age at first calving (AFC) is 24 months, based on optimising the best performance efficiency and production of the heifer, while ensuring an achievable heifer rearing programme.

Although the industry target has been 24 months for numerous years, reported AFC for different countries worldwide are all greater than 24 months – the latest reported median AFC for the UK was 27.6 months from 500 herds, with the top 25% reporting a median of 26.4 months.

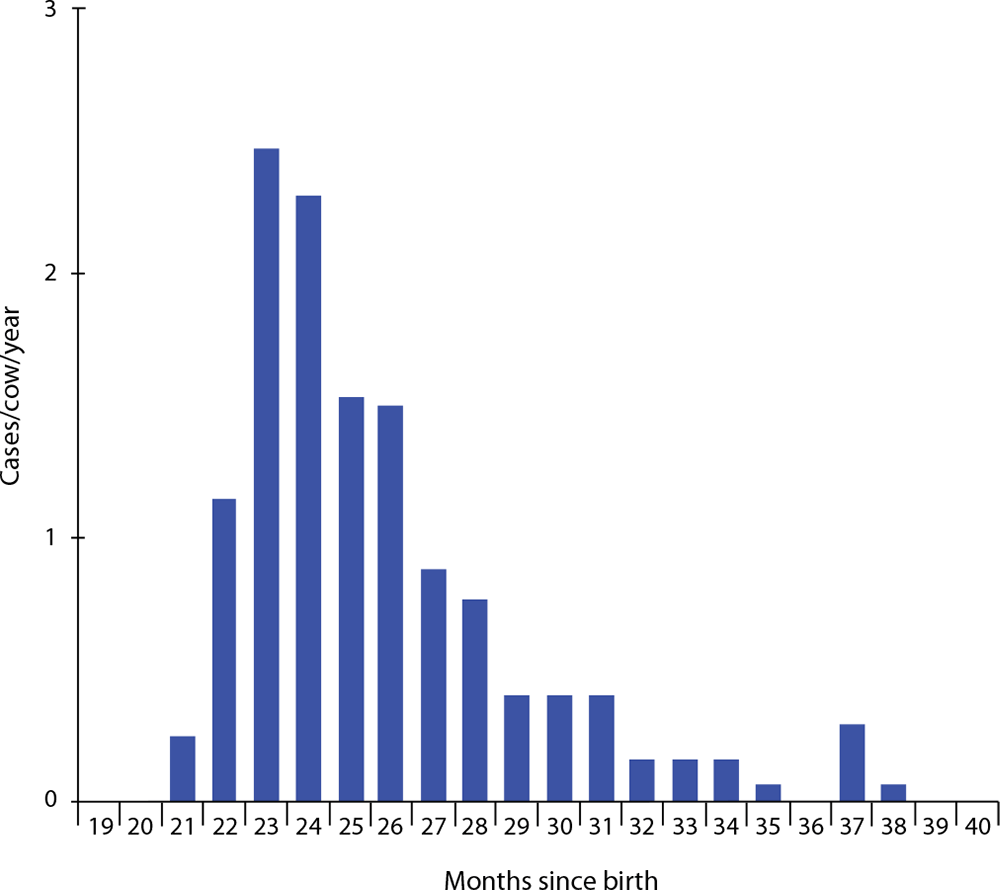

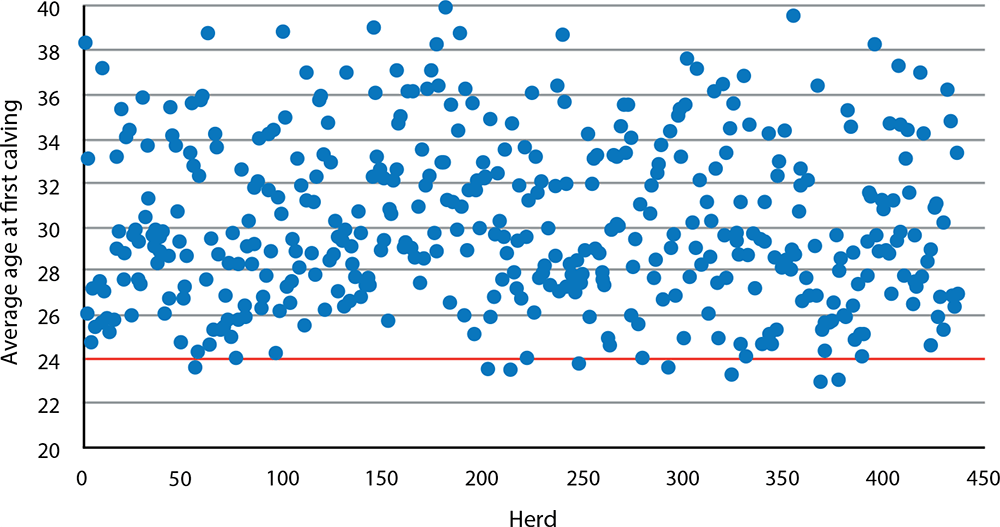

A wide variation of AFC exists at herd level and at an individual heifer level within a herd, as shown by Figure 1a (individual herd) and Figure 1b (numerous herds).

What does delayed AFC potentially represent?

AFC is an overall representation of the rearing period, in terms of both management and decision-making. It is a historic representation of the rearing period and better rearing period key parameters exist that can be monitored, such as growth rates, mortality rates and 21-day pregnancy rate of nulliparous heifers.

AFC also acts as a proxy for bodyweight and is used as it is easy data to collect. In theory, a heifer should calve for the first time at 90% of its adult mature bodyweight (based on the average weight of third lactation cows) and conceive at 55% to 60% of its adult mature bodyweight.

Suboptimal growth at an early age has been reported in British heifers, which has subsequently resulted in animals not reaching the adequate size at the start of breeding2 – most likely due to the fact the onset of puberty has been related to bodyweight and age, with puberty occurring at approximately 43% of mature bodyweight3.

This link was highlighted in a study by Bazeley et al (2016), where a variation in growth rates resulted in a variation in bodyweight at time of first service at 420 days, with the mean bodyweight being 21kg lighter than the target of 374kg4. Therefore, a delay in breeding, resulting in a delay in AFC, can reflect poor growth rates in heifers. Poor growth rates can be related to multiple factors, including inadequate energy intakes; disease, such as endemic calf diseases and parasitic diseases; and poor housing conditions, requiring extra energy expenditure.

What impact does AFC have on first lactation performance?

It is important for incoming replacement heifers to perform at maximum efficiency, both economically and in terms of health. AFC has been shown to have an impact on the future performance of first lactation heifers. The potential exists for AFC to affect the future milk production, as the majority of mammary gland development occurs prior to first calving, with suggestions a lower AFC could result in underdevelopment of the udder.

The research performed at the level of the individual heifer is conflicting, with some studies showing no significant difference and others indicating milk yield increases with increasing AFC1. However, this interaction does not appear to occur at a herd level5-7, and unless the milk price is more than 43p/L, extending the AFC does not make economic sense.

The reproductive performance of the first lactation heifer falls as the AFC rises, with the number of days open increased, poorer conception rate to first serve, decreased 100 day in calf rate and increased 200 day not in calf rate. Unfortunately, the main reported reason for culling in first lactation heifers is infertility, with 40% of first lactation heifer exits being due to poor fertility8. This may potentially explain the link between the decrease in the odds of survival to second lactation and increasing AFC, which has been shown in several studies1,9,10.

The majority of first lactation heifers are removed towards the end of lactation, with the average removal time being 322 days in milk (DIM)8. However, when looking at the spread, approximately one-third of heifers are culled within the first 100 DIM – suggesting these removals were forced, rather than voluntary, and, therefore, may be inadequate management of first lactation heifers, especially around the transition period.

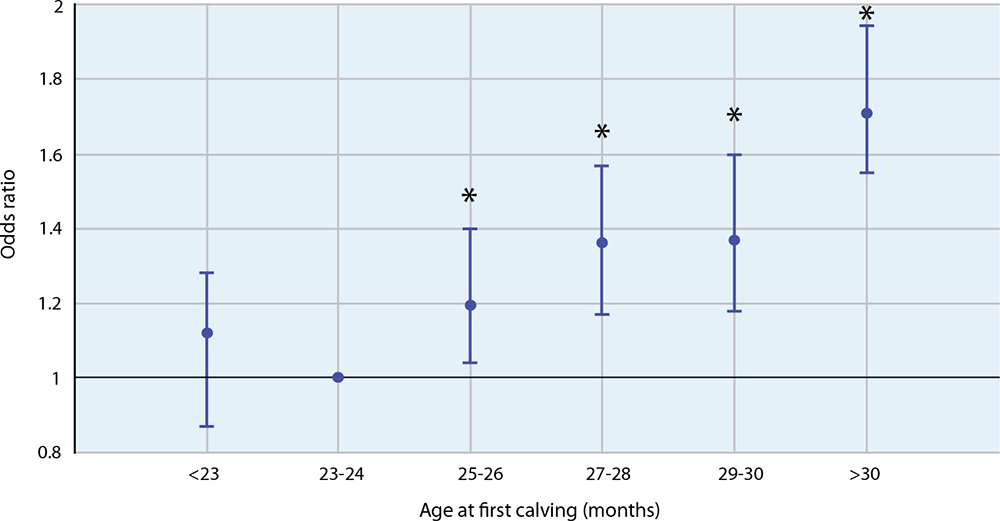

AFC has been shown to affect whether a heifer survives its first lactation, with the odds of removal prior to completing first lactation increasing as the AFC increases1,9,11, as shown in Figure 2. This has both large welfare and economic implications. The break-even point for heifers, in terms of rearing costs compared to milk production, is usually around second lactation, depending on the milk price and rearing costs11. Ideally, a replacement heifer has been selected to replace an older cow to improve the production and performance of the herd (a voluntary/economic cull); therefore, it is assumed the removal of a first lactation heifer is a forced/involuntary cull.

A forced/involuntary cull is defined as culling a cow where no possible productive future exists and, therefore, it is assumed it is due to health issues or fertility problems.

If a high forced cull rate occurs within first lactation heifers, it is assumed they are not adapting to being an adult cow and have significant issues, which highlight a potential welfare problem on farm. This is re-enforced by the finding herds that have a higher multiparous culling rate also tend to have a higher primiparous heifer culling rate, suggesting a large number of forced culls happen on farm.

Economics

Heifer rearing is a large component of the total costs of a dairy farm, with estimations at 15% to 20% of costs – the equivalent of 2.6p/L on average12,13, a cost that should be reduced to 2p/L4.

The importance of monitoring the AFC at a herd level includes maximising welfare by reducing the incidence of disease, but also for optimising the efficiency of heifer rearing and maximising first lactation production for profitability. The economics of heifer rearing is dynamic and depends on farm management decisions – for example, whether sexed semen is used and whether heifers are reared by someone else – as well as other factors the farmer has no/less control over. These include the strength of the British pound, the price of cull cows, the market value of dairy-beef cross calves, feed costs and the price of milk.

One main factor is the number of replacement heifers reared, which will depend on voluntary and involuntary culling rates, as well as the calving interval and live calving rate of the dairy herd. It will also be affected by factors in the heifer population, including mortality rate, AFC, nulliparous heifer reproductive performance and involuntary heifer culling rate14. In terms of the effects of AFC on the economics of heifer rearing, the rearing phase most variable with varying AFC is the post-weaning to pregnant heifer stage, as gestation is set at approximately 283 days and the pre-weaning stage being approximately 4 to 6 weeks on farm.

The average cost of an extra day as a post-weaned open heifer has been reported as £1.65 per day, which is the equivalent of 5.5L of milk sold per day at 30p/L. An extra month before calving costs the farmer, on average, approximately £50 per heifer. A lower AFC not only reduces the rearing costs, but also decreases the number of replacements required and, therefore, a potential extra income stream for the farmer if he or she can sell surplus heifers.

For more information investigating the costs of heifer rearing on individual farms, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board has developed a heifer rearing cost calculator.

Looking forward

While the average AFC is seen as a standard key performance indicator, it clearly gives more than that – it gives us an insight into the success of the heifer rearing programme and what expectations we can have for the future of the herd. It is an important area around which to have discussions with farmers and look at how their management decisions on farm potentially influence this, as well as the potential implications these have for the future performance of these heifers.