12 Aug 2022

An update on sheep scab control

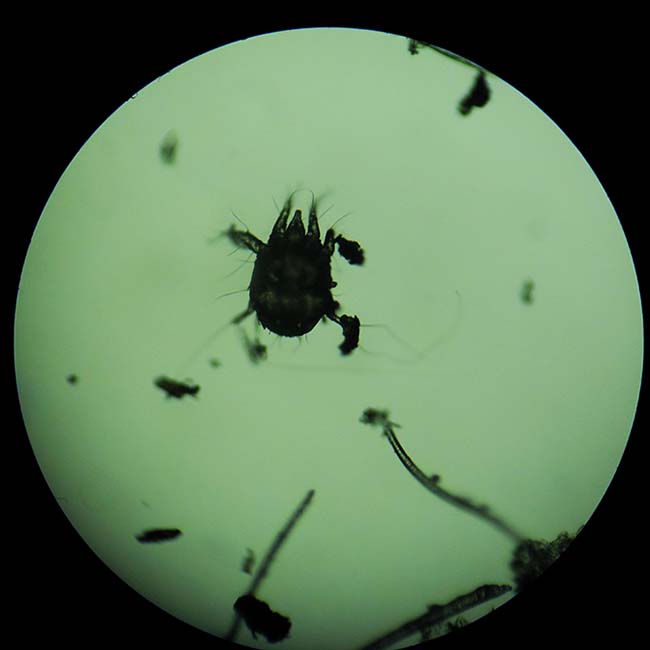

Fiona Lovatt looks at research into this disease – caused by infestation with the parasitic mite <em>Psoroptes ovis</em> – and disease control.

Figure 2. Sheep scab is more common in the winter and of particular concern to those that share common grazing. Clinical sheep scab found on this Swaledale fell ewe at a winter gather.

“Sheep scab”, or psoroptic mange, is a highly pathogenic and contagious disease of sheep that has huge implications to sheep welfare and economics.

A large collaborative research project funded by the VMD – and involving the Moredun Research Institute and the universities of Bristol, Glasgow and Nottingham – has been researching sheep scab control with work packages that have concentrated on surveillance data1,2 diagnostics, disease modelling3, social science4 and knowledge exchange5,6, with many of the resulting publications, listed in the references, free to access.

Alongside is a focused and practical Rural Development Programme for England (RDPE)-funded project to control scab among clusters of flocks in Herefordshire and Shropshire, as well as areas of the south-west and northern England.

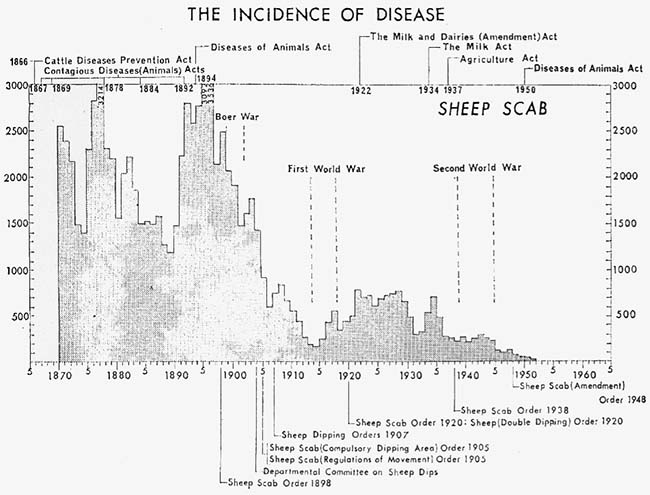

Caused by infestation with the mite Psoroptes ovis, sheep scab has a long history in the UK (Figure 1). Despite some scab-free years between the 1950s and 1970s, incidence has increased exponentially since its reintroduction to the UK in 1972. It is widespread and persistent throughout all devolved regions of the UK7-9, though distinct variations exist in national legislation and disease control initiatives.

The analysis of surveillance data has shown these to have had different, though not necessarily defining effects1,2.

Recent calculations put sheep scab cost to the UK sheep industry at between £78 million and £202 million on an annual basis10.

The mite abrades the skin surface to feed on the serous exudate and disease is largely caused by an allergic reaction to the mite faeces, which causes an inflammatory response and debilitating dermatitis (Figure 2).

Spread is direct from sheep to sheep or indirect via equipment, fencing or personnel, as mites can remain infective in the environment for up to 16 days (Figure 3).

- The life cycle of the mite is 14 days and the population doubles every six days.

- Mites can live off the sheep, in wool tags, for up to 16 days.

- Sheep-to-sheep contact is the main source of disease spread, but contaminated lorries and trailers are also a risk.

- Shared equipment – such as shearing, scanning or handling facilities – and workers’ clothes can spread mites.

- Sheep can be subclinically affected with scab for months before any signs are apparent.

- Clinical sheep scab can be diagnosed by the presence of live mites scraped off the edge of lesions (Figure 4).

- Both clinical and subclinical sheep scab can be diagnosed by blood ELISA, which reliably detects antibodies as quickly as two weeks after exposure.

- Blood samples of 12 sheep will detect sheep scab at 20 per cent prevalence with 95% confidence – this can be used on any sized flock as long as they are run as one epidemiological group. Separate flock groups should be tested by taking further groups of 12 samples.

Disease control

Control is complicated due to subclinical disease with no visible signs that may last for a lag of weeks or months between infestation, and a noticeable increase in mite numbers and lesion area11. Subsequent or secondary infestations in the same sheep are characterised by an extended subclinical phase and reduced mite numbers, lesion size and clinical signs12, which further complicates diagnosis and subsequent control.

Risk of scab infestation increases dramatically for flocks that have persistently or regularly scab-infested neighbours, or those that use common grazing7. Consistent findings from studies have suggested that scab control is hampered by social factors, including a stigma of reporting cases, mistrust, as well as poor quarantine procedures for incoming sheep7-9.

Control strategies are commonly focused on “hot spots” around the country, with recent modelling work suggesting that tackling long-distance movements via sales and markets may be key to national control3.

Recently published social science suggests that farmers’ individual sheep scab control strategies are shaped by their perceptions of risk, which are influenced by where they live and contrasting motivations; this includes fatalistic views that suggest scab is both unpredictable and uncontrollable, as well as the influence of both responsibility and the impact on reputation4.

Historically, disease control strategies have relied on chemotherapy, which in the recent past has meant either plunge-dipping in organophosphates or injecting with macrocyclic lactones – both of which have limitations and legitimate concerns from an environmental perspective due to residues, ecotoxicity and the consequences that result from increasing the selection pressure for the development of anthelmintic resistance.

Furthermore, the use of injectable macrocyclic lactones has been complicated by the development of resistance by scab mites13, and practically this means plunge-dipping in organophosphate is currently the only consistently reliable method for the control of scab. The use of jetters, sprays or showers is neither effective or responsible, with potential legal consequences for anyone who either sells or purchases organophosphates to apply by such methods.

To purchase or use organophosphate dip, it is necessary to hold an NPTC Level 2 Award in the Safe Use of Sheep Dip14. Contract mobile dippers cover the country and can be accessed via an online directory15.

Strategies to limit the undesirable consequences of chemical control include mantras such as “use as little as possible, but as much as necessary”, but these depend on the availability of reliable diagnostics – both to confirm diagnosis during an apparent outbreak of disease, as well as to identify animals that are affected without any clinical signs of disease. These may include recently infested sheep during the lag phase before clinical signs become apparent or apparently “immune sheep” that are infested with mites, but show no clinical signs.

The Moredun Research Institute-developed sheep scab serodiagnostic16 that detects host antibodies specific to the recombinant mite allergen (Pso o 2) has been described as a “game changer”. Blood samples are currently tested once a week at Biobest Laboratories, with results reported most quickly for samples that arrive by a Wednesday17. This blood test has been shown to have a high sensitivity (98%) and specificity (97%), and the ability to detect scab within two weeks of infestation.

The early diagnosis of sheep scab via the ELISA forms a critical component of the current RDPE-funded sheep scab control programme in England. This is via interpretation of the results from a sample of 12 sheep to indicate the sheep scab status of a whole flock group.

Originally, sheep scab ELISA results were reported as “positive”, “negative” or “uncertain”, depending on whether the optical density showed the antibody levels to be above, below or close to a fixed cut-off point. Now, an improved Bayesian model is used to more accurately interpret the disease status of each flock based on the knowledge of prior flock risk levels in combination with actual test results.

Following a successful period of validation within the RDPE-funded project, the model is now being used to assist in the interpretation of all ELISA flock results within the project, and its wider use should increase confidence in the test for practitioners and farmers.

Conclusion

Sheep scab has been a difficult nut that we have failed to crack for many years and we continue to face considerable challenges as an industry. However, it is reassuring to know that we are making progress with good diagnostics, readily available and trained dipping contractors, and whole teams of good brains are contributing to improve national control measures.