5 Dec 2016

Avoiding pitfalls in using selective dry cow therapy

Peter Edmondson discusses the role of vets in reducing antibiotic use for this condition, as well as common difficulties and ways of managing perceived treatment failure.

Figure 2. Poor teat preparation creates a risk of infusing bacteria on the tube nozzle.

Vets and farmers are getting more comfortable with the concept of selective dry cow therapy (SDCT), where individual cows are targeted for antibiotic dry cow therapy (ABDCT).

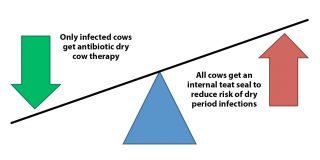

Only cows with known subclinical mastitis, or quarters with a history of clinical mastitis, receive antibiotic treatment at dry off. ABDCT accounts for about 40% of all antibiotic use in dairy cows, and moving to SDCT reduces the use of antibiotics and follows responsible use guidelines.

One of the biggest fears with SDCT is an increase in clinical mastitis when the perceived “protection effect” of using ABDCT is taken away. It is well known blanket use of internal teat sealants helps prevent dry period infections and results in a 25% to 30% reduction in clinical mastitis in the following lactation. More research probably exists into the use of internal teat sealants than any other mastitis area.

SDCT makes sense. About 80% of cows are infection-free at dry off, so no benefit exists from administering antibiotics at dry off. After all, you don’t give antibiotics to healthy animals.

It is well established teats do not seal effectively during the dry period. In high-yielding cows, up to two-thirds of teats are open a week after dry off and this drops down to slightly lower than 50% open 50 days after dry off. These cows are at great risk of picking up dry period infections, even if they had ABDCT, so all cows benefit from being sealed at dry off.

A plethora of research exists showing ABDCT does not influence the incidence of dry period infections. However, some farmers and vets rely on this as a crutch.

Vets need to persuade farmers, and be comfortable, that moving to blanket use of internal teat sealants and selective use of ABDCT is best for our cows (Figure 1).

The UK has slightly fewer than 1.9 million dairy cows. Let’s call it 2 million for ease of maths. Assuming a 25% culling rate, 1.5 million cows are dried off every year. About 80% of these are infection-free and some will have had a case of clinical mastitis, so potential exists to stop using ABDCT in probably half of these cows. This means ABDCT use can be saved in about 750,000 cows each year.

Slightly more than 50% of cows get a seal at dry off; that’s 750,000 cows. This means the potential exists to reduce clinical mastitis by 25% to 30% in these cows that do not get a teat seal at dry off.

If you assume the UK mastitis incidence is 40 cases per 100 cows per year, and an internal teat seal reduces mastitis by 25%, the opportunity exists to save 75,000 cases of mastitis each year. Think of the welfare benefits for the cows, less hassle for the farmers, more milk being sold – it’s a win-win situation.

Vets and farmers have to play their part in reducing antibiotic use. SDCT offers a great opportunity to achieve this, with the potential to reduce ABDCT use in 750,000 cows each year – meaning three million dry cow tubes. It can also save antibiotic use in 75,000 cases of clinical mastitis – five tubes per case means a reduction of 375,000 milking cow tubes.

The biggest concern with SDCT is a rise in cell count or clinical mastitis. As prescribers and dispensers, vets have a responsibility to help our farmers use antibiotics and internal teat seals responsibly and in the most appropriate way.

Manage perceived failure with SDCT

Years ago, a dairy client talked to the author about homeopathy. He was surprised the author did not favour its use as he had found it brilliant in reducing cell counts in one of his two dairy herds. The cows were milked in parlours side by side, and were housed and managed the same way. The herd was split for ease of management.

The author spoke to the farm manager about homeopathy. He said the cell count in one herd had fallen from about 250 to 175 after the owner bought the expensive homeopathic solutions. He also told the author he had dropped the bottles, they were not used and he never told the owner.

The owner associated the purchase of homeopathic solutions with reduction in cell count as the timeline matched what he thought was the start of treatment.

All too often, vets encounter a scenario where someone remembers something at a particular time and assumes this was the key factor responsible for change. By digging deeper, it is often found no association exists.

Vets need to bear this in mind if a farmer says the cell count or clinical mastitis has increased after moving to SDCT. In some situations, the problem will be something going wrong during the change to SDCT, such as poor infusion technique or use of incorrect thresholds. However, in most cases, something else occurs unrelated to SDCT.

When things go wrong, it is human nature to agree with the farmer and return to blanket ABDCT. However, the author has come across these situations many times because all the vet has done is revert to blanket ABDCT use and not investigated what has gone wrong. No long-term solution exists for the farmer, who then gets frustrated.

Fortunately, vets have access to a range of tools that can help analyse mastitis data and cell counts at the click of a button, and see what is going on epidemiologically.

Common pitfalls

Go-alone and know-it-all farmers

We all know farmers who think they are vets. They know more about SDCT than anyone on the planet, set their thresholds and implement this without consulting vets. In fact, many farmers have probably been carrying out SDCT for some time that vets may not be aware of.

Some get it right, but others get it wrong. The author recalls a referral to an organic herd with a cell count above 400 that was losing more than half of its milk cheque in penalties. The farmer was in danger of having its contract stopped. This farmer got a letter from his organic organisation six months earlier asking him to reduce antibiotic use and stating one way he could do this was by moving to SDCT.

The farmer researched online and decided a threshold of 200 was used by many people and implemented this, even though the herd cell count was fluctuating between 250 and 300 at the time. He never consulted his vet, even though he had fortnightly visits. This was a seasonally calving dairy herd, so everything went well until the herd started to calve down, when cell counts start going through the roof.

Bacteriology identified Staphylococcus aureus and he ended up in crisis management, dumping milk from cows with the highest percentage contribution to the bulk tank.

All the farmer had to do was consult his vet. Alternatively, his vet could have raised SDCT in discussion at a routine visit and offer guidance on how this could best be achieved in his herd.

It is better to be proactive than reactive, especially with SDCT where many conversations may be needed over a couple of months before farmers feel comfortable to make the transition.

Incorrect thresholds for SDCT

Farmers need guidance on which cows should receive antibiotics at dry off. As many opinions exist on thresholds as camels riding around the desert. The best approach is a gentle one, starting with low thresholds so farmers can see SDCT works with no adverse effects. Vets are far better off agreeing figures with clients than imposing a figure. Compromise is a better way of starting to inspire confidence in the process.

If a herd has a low cell count, the risk of things going wrong is slim in relation to the cell count rising. Thresholds need to be lower for herds with a high cell count as the risk of error is higher.

It is always worth carrying out bacteriology on high cell count cows and bulk tanks to establish what bacteria are present. If Streptococcus agalactiae is isolated in any samples then mastitis management should be reviewed and blanket dry cow therapy continued until it has been eradicated, before moving to SDCT.

Poor hygiene at dry off

Scrupulous hygiene is needed before administration of any intramammary preparation for milking or dry cow tubes. A risk exists of introducing infection with poor teat preparation (Figure 2).

How many cows have you dried off and infused with an internal teat seal? It is surprising a large number of vets have never carried out this procedure, so will not be aware of the challenges. We may assume most farmers do a great job with infusion, but are they? The only way you find out is by being present at dry off.

Risk will be minimal with good hygiene practices (Figures 3 and 4). Some farmers infuse as if it is a surgical procedure with meticulous hygiene. Best practice is to ensure best practice is understood; show this to the person who dries off the cows and get them to demonstrate it. A written standard operating procedure is invaluable, provided it has been reviewed first.

Cows should be dried off in adequate facilities and never in a foot crush or behind a gate, where the risk of contamination will be high.

Limited individual cell count results

The more cell count information you have, the better the decisions you make. Monthly cell count testing will give the most accurate information. Looking at the last three cell counts before dry off will give a good indication on subclinical mastitis status.

Ad hoc samples will be taken from some herds for cell count testing. They may rely on one or two individual results before dry off. This can be misleading, so the thresholds should be lower due to limited information available.

California mastitis test

The California mastitis test (CMT) is a crude cow side test to give an indication of subclinical infection. It is not accurate enough to pick up all infected quarters as changes are readily seen when cell counts are above 400. Operator variation and error can occur. This should never be used on its own to identify cows for SDCT.

However, the CMT can be used to check a cow’s status before drying off. Consider a cow with its last three-monthly cell count results below 100. The farmer carries out a CMT and identifies high cell count quarters. These could have become infected since the last milk recording, so would benefit from antibiotics at dry off.

It is always worth training farmers in how to use the CMT. Their results can be compared to a numerical figure, using cell count testers.

Using no products at dry off

Some farms may decide to stop milking cows and not use any product at dry off to cut costs. This will leave the udder vulnerable to environmental infections entering during the dry period, so is not recommended.

Monitoring progress

Once a farm moves to SDCT, vets should continue to monitor trends with herd cell count and changes to individual cows. This will reassure vets and farmers this process works and is easy to carry out. Trends of clinical cases can be monitored in the first 30 days of lactation before and after transition to SDCT.

Many countries have never allowed blanket dry cow therapy and where antibiotic use at dry off has to be justified on a cow-by-cow basis. There is nothing to fear from SDCT, provided vets manage the process correctly, educate and demonstrate best practice, advise on the correct thresholds and monitor progress.

SDCT will be the norm in the not-too-distant future for all cows.