23 Apr 2024

Anna Bruguera-Sala considers national steps taken to tackle this disease, as well as how vets can educate farmers.

Image © Mike / Adobe Stock

Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) was first reported in cattle in the UK more than 70 years ago. The disease, caused by a virus, relies mostly on cattle born persistently infected to survive in a herd. Access to affordable diagnostic tests and vaccines has made the virus easy to identify and control, leading to BVD eradication in many European countries.

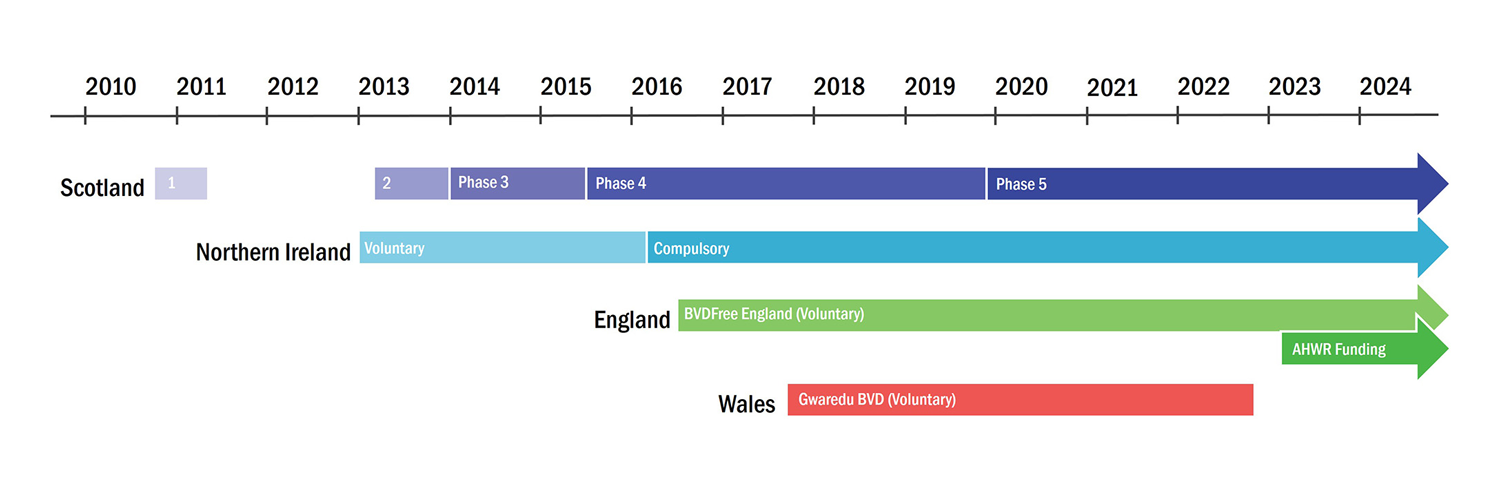

In the UK, Scotland launched the first nationwide eradication scheme in 2010, which became compulsory in 2013. Northern Ireland followed suit in 2013, with legislation coming into force in 2016. In England and Wales, BVD testing and control is voluntary, but different initiatives have been launched to support control efforts.

Since the start of their respective eradication schemes, both Scotland and Northern Ireland have reported a 75% reduction in the number of herds that are not negative or positive for BVD. However, virus transmission is still happening in all four UK nations.

Stricter legislation will be necessary if the UK is to achieve freedom from BVD. In the meantime, farm animal veterinarians continue to play a key role in guiding and encouraging farmers to control the disease.

Keywords: BVD, eradication schemes, Scotland, Northern Ireland, England, Wales

Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) is an endemic disease of cattle that has a significant negative impact on the animals’ health and welfare, and can cause substantial economic losses to cattle producers (Yarnall and Thrusfield, 2017; Haw, 2019).

To survive in a cattle population, the virus relies mostly on persistently infected (PI) animals – cattle that are born congenitally infected (Larson, 2015). Access to reliable and affordable diagnostic tests (Lanyon et al, 2014), as well as effective vaccines (Newcomer et al, 2017), have made BVD PI cattle easy to identify, destroy and prevent. Therefore, the disease is relatively straightforward to control and eradicate, as shown by the success of eradication programmes carried out in the Scandinavian countries (Lindberg et al, 2006).

It has been more than 70 years since BVD was first reported in the UK (Woods, 2022), and almost 30 years since the Shetland Islands were declared free of the disease (Synge et al, 1999). After that, a few other regional eradication schemes emerged across the UK (Truyers et al, 2010; Booth and Brownlie, 2012; Azbel-Jackson et al, 2018), but it was not until 2010 when Scotland became the first nation to launch a full-scale BVD eradication programme (Scottish Government, 2024).

Eradicating BVD from a herd or region has been shown to have greater benefits than costs for the cattle industry (Stott et al, 2012; Haw, 2019); however, the UK still has a lot of work to do to achieve freedom from BVD.

This article will review the progress made by the different UK nations’ BVD eradication schemes (Figure 1 and Table 1) and discusses how farm animal vets can make the most of current initiatives to encourage farmers to continue working towards BVD eradication.

The Scottish Government, with support from the cattle industry, launched its BVD eradication scheme in 2010 (Scottish Government, 2024). The scheme took a phased approach: the first phase was voluntary and subsidised, and ran until April 2011.

Annual BVD screening of all breeding cattle herds became compulsory in February 2013, with the start of phase two (see The Bovine Viral Diarrhoea [Scotland] Order 2019). The Scottish scheme is based on serological (antibody) testing at herd level, followed by virological (antigen) investigations in farms that show exposure to the virus.

Herds are given a “negative”, “not negative” or “positive” status based on the test results.

The first mandatory control measures, including cattle movement restrictions, came into force with phase three, in January 2014. The requirements were tightened in phases four and five in June 2015 and December 2019, respectively. Additionally, with the start of phase four, the number of allowed testing methods was reduced from six to only three. Bulk milk tests were removed as an option to accelerate the scheme’s progress. This was due to the challenges associated with interpreting antibody-positive milk results in vaccinated herds, as well as research indicating that it takes longer to follow up positive results from milk samples compared to blood (Duncan et al, 2016).

The scheme’s BVD database on ScotEID has been active since 2013 (ScotEID, 2024a). On the “BVD lookup”, anyone can check a herd’s or individual animal’s status by searching a county parish holding (CPH) number or official ear tag number. The “PI locator” was added to ScotEID in 2019. It lists the locations of all herds that have retained suspect or confirmed PI cattle for more than 40 days since their discovery, with the aim to encourage faster PI removals (ScotEID, 2024b).

Another element of the Scottish scheme is the Compulsory BVD Investigation (CBI), which was introduced with phase five. Since then, any herds that have been “not negative” for 15 months or longer must have a BVD status for all the cattle in the herd within 13 months. Once all the animals have been confirmed “negative”, an approved vet can sign a CBI completion certificate. In the 12 months following a CBI, the farmer must also test all born calves for BVD virus. To sign a CBI certificate, vets must have completed the SRUC online BVD module (SRUC, 2020).

No more changes have been introduced to the Scottish scheme since the start of phase five in December 2019. However, in November 2023, the Government launched a consultation about the potential implementation of a sixth phase. The new phase would introduce further restrictions, could change the testing requirements and reduce the time given to complete a CBI (Scottish Government, 2023). The consultation period closed on 7 February 2024.

At the end of the voluntary phase of the Scottish BVD eradication scheme, it was estimated that 30% of tested herds had been exposed to BVD virus (“not negative” status; Scottish Government, 2015a). By August 2015, that figure had decreased to 15% (Scottish Government, 2015b). A total of 2,624 PI cattle had been identified by then, 481 of which were still alive.

After the removal of milk tests in 2015, the number of PI cattle found per year increased from 759 and 742 in 2013 and 2014, respectively, to 1,479 in 2015 (J Purcell, personal communication, August 2016). As of 5 February 2024, only 7.2% of Scottish holdings were classed as “not negative”, and 0.1% were “positive” (EPIC, 2024). The author could not find data on the current number of PI cattle that are alive in Scotland; however, as of 23 February 2024, only two holdings were listed on the ScotEID BVD PI locator (ScotEID, 2024b).

Scotland has made remarkable progress in its efforts to eradicate BVD. The prevalence of “not negative” and “positive” herds has decreased from 30% to only 7.3% in 13 years. If stage six is implemented and the progress is accelerated further, Scotland will likely be the first UK nation to achieve BVD freedom.

| Table 1. Comparison of UK nations’ bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) eradication programmes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK nation | Status | Year Started | Year ended | Legislation | Movement restrictions | Database available | Current stage | Results | ||

| Year | Herd level | Positive animals | ||||||||

| Scotland | Voluntary | 2010 | Ongoing | Yes | Yes | Yes | Phase five, phase six consultation ended February 2024 | 2011 | 30% (Scottish Government, 2015a) | Unknown |

| Northern Ireland (NI) | Voluntary | 2013 | Ongoing | Yes | Yes | Yes | Consultation on compulsory scheme ended December 2022 | 2016 | 11% (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2017) | 0.68% |

| Compulsory | 2016 | 2024 | 2.76% (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2024c) | 0.21% | ||||||

| England (Prosser et al, 2022) | Voluntary | 2016 | Ongoing | No | No | Yes | Annual Health and Welfare Review funding available for BVD herd tests | 2016-20 | 13.5% to 20% | 0.4% to 1.5% |

| Wales (Animal Health and Welfare Wales, 2023b) | Voluntary | 2017 | 2022 | No | No | No | Consultation on compulsory scheme ended August 2022 | 2018 | 27% | Unknown |

| 2022 | 23% | Unknown | ||||||||

Northern Ireland (NI) was the second nation to launch a BVD eradication scheme. The NI scheme mirrors the Republic of Ireland’s programme, and also started with a voluntary phase in January 2013, followed by legislation in March 2016 (The Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Eradication Scheme Order [Northern Ireland] 2016).

Both the Republic of Ireland and the NI eradication schemes are based on virological (antigen) BVD testing at the individual animal level. Since 2016, in NI, all newborn calves must be tag tested within seven days of birth. Aborted calves, stillbirths and calves that die after birth must also be tested, and any inconclusive or positive results must be followed up, including testing the relevant dams (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2024a).

Cattle with positive or inconclusive BVD antigen results must be isolated from the rest of the herd, and cannot be moved off the herd, other than directly to slaughter. The movement restrictions also apply to cattle that are waiting to be tested. Herds with active BVD infection may be prohibited from moving any animals on or off the holding.

During the first year of the compulsory NI programme (2016), approximately 11% of tested herds had at least one BVD virus positive test result. At the animal level, 0.68% of antigen tests were positive (3,521 positive cattle out of 517,819 tested). Of these, 2,325 were re-tested and 87.4% remained positive, being confirmed as PI (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2017). As of January 2024, the percentage of herds with an initial positive or inconclusive result had dropped to 2.76%, with an animal-level prevalence of 0.21% (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2024b). Between December 2022 and November 2023, a total of 1,112 cattle tested positive, and 9 herds retained 10 BVD positive animals for at least 4 weeks.

The NI scheme has made significant progress since 2016; however, a significant number of cattle were still testing positive in 2023, suggesting that the virus is still spreading in the country. In 2022, the NI Beef and Lamb Farm Quality Assurance scheme introduced a change to make the retention of any BVD-positive cattle a non-compliance, meaning that if a producer retains a PI animal, they will lose their accreditation (Livestock and Meat Commission, 2022). This measure will add more pressure to remove infected animals.

In the same year, the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) launched a consultation to gather opinions on the proposal to introduce further control measures to improve the scheme’s progress (DAERA, 2022).

With the new restrictions, herds found to have BVD would not be allowed to move animals on or off the farm other than directly to slaughter, and owners would be required to test any cattle born before 2016. The responses to the consultation, which were published in October 2023, were generally favourable (DAERA, 2023).

DAERA is in the process of developing new legislation to implement the restrictions. With the restoration of an executive government in Northern Ireland in January 2024, optimism exists that this development may facilitate progress, strengthen the BVD eradication scheme and encourage farmers to continue reducing the virus prevalence in NI.

“[It] is essential that vets educate and engage farmers to remove [persistently infected] animals…”

At the time of writing, no compulsory BVD eradication scheme exists in England. However, stakeholders in Great Britain (GB) identified BVD as a priority for the cattle industry in 2012 (GB Cattle Health and Welfare Group, 2012).

This led to the creation of BVDFree England: an industry-led, voluntary BVD scheme that was launched in 2016 (BVDFree, 2024). The scheme offers two testing options: youngstock antibody check tests or individual antigen testing of all calves born for two years. For samples to be counted towards the BVDFree accreditation, they must be sent to an approved laboratory and, when a herd has achieved two consecutive years of negative herd tests, they can apply for a “test negative herd status” and certificate. The application has to be done with a BCVA BVD-accredited vet: a vet who has completed the online BVD Veterinary Adviser Training (BCVA, 2024). The scheme also offers a database to check herd and animal BVD statuses.

Based on BVDFree testing results, between 2016 and 2020, Prosser et al (2022) reported that the BVD prevalence among participating farms was 13.5% for beef and 20% for dairy herds. At the animal level, between 0.4% and 1.5% of tests were virus-positive. Data shared by veterinary practices after the “BVD Stamp It Out” initiative – a project that offered a funded check test and PI investigations for about 50% of breeding herds in England between 2018 and 2020 – suggest that the herd-level prevalence in some English regions could be as high as 44% (Donovan, 2020).

One of the aims of BVDFree is to work with the Government to develop a mandatory eradication scheme. The cattle industry has expressed support for the ambitious plan to eliminate BVD from GB by 2031 (Ruminant Health and Welfare, 2021). However, given the current prevalence estimates and the lack of compulsory measures, the decline in BVD prevalence in England is likely to be slower. Although engagement with the voluntary BVD scheme increased during the Stamp It Out period, it had already declined by 2020 (Prosser et al, 2022).

Despite the lack of mandatory BVD eradication measures, recent developments, such as the introduction of the Annual Health and Welfare Review (AHWR), funding and the updated Red Tractor farm assurance standards, offer an opportunity for progress in England. Since 2022, English herds with more than 11 dairy or beef cattle can apply for an AHWR to do a BVD herd test (Defra, 2023).

Additionally, as of October 2022, compliance with the Red Tractor standards requires all cattle herds to have a BVD eradication plan in place, and evidence of test results on their herd health plans (Assured Food Standards, 2024). These recent changes offer hope for enhanced progress in controlling BVD within England’s cattle industry.

In May 2017, the Welsh Government, with cattle industry support, launched Gwaredu BVD: a voluntary and subsidised BVD eradication programme.

Until 31 December 2022, cattle producers in Wales had access to funded veterinary visits and a free BVD herd test (youngstock antibody screen), which was done during the herd’s annual bovine tuberculosis test. If a herd tested positive for BVD, a further £500 was available to carry out a PI investigation (Animal Health and Welfare Wales, 2023a). The programme also introduced certificates to share the farm’s status at cattle sales and promote informed purchasing. At the end of this subsidised phase, 85% of Welsh herds and all veterinary practices in the country had taken part in the scheme. In 2018, 27% of farms had a positive herd test. By 2022, this percentage had decreased to 23%. A total of 1,296 5PI hunts were conducted over the five-year period and 1,582 PI cattle were identified (Animal Health and Welfare Wales, 2023b). After the subsidised phase ended, Welsh farmers were encouraged to continue testing and monitoring for BVD. However, it is unknown to the author how many PI cattle have been removed or continue to be alive in Wales.

In June 2022, the Welsh Government launched a consultation on the potential introduction of a compulsory BVD eradication scheme (Welsh Government, 2022). Despite the industry’s responses being mostly supportive of the mandatory measures, no subsequent announcement has been made regarding the development or launch of such a programme in Wales. Similarly to what happened at the end of the BVD Stamp It Out initiative in England, it is likely that engagement with BVD eradication efforts in Wales declined following the conclusion of the voluntary scheme. Without additional pressure on Welsh cattle producers, BVD eradication may remain elusive.

Each UK nation is at a different stage in its BVD eradication journey (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Cattle vets across the country must continue to work to drive progress alongside farmers. In nations where BVD control is voluntary, the choice to manage BVD or not will be affected by many factors.

However, farmers with a close relationship to their vet have been shown to be more proactive in BVD control (Prosser et al, 2022). In the 2021 UK National BVD Survey, 57% of respondents were vaccinating against BVD and 64% of those said they were motivated to do so by vet advice (Boehringer Ingelheim, 2024). These findings highlight the important role that vets play in advocating and guiding farmers towards effective BVD control strategies.

In this article, the author has reviewed several initiatives that will already be encouraging farmers to take action against BVD. In NI and Scotland, farmers should already be engaging, at least, with BVD testing, or their herds could face being put under movement restrictions. Farm assurance schemes are an additional source of pressure to control BVD. In England, all eligible beef and/or dairy herds should be encouraged to apply for the AHWR funding – unless the same holding has already received funding for another species – and join the BVDFree scheme.

Private cattle health accreditation schemes also play a role in BVD eradication efforts. In 2012, it was estimated that approximately 14% of UK herds were members of a Cattle Health Certification Standards (CHeCS) accredited scheme (Brigstocke, 2012). In a survey by CHeCS in 2019, 78.3% of respondents were targeting BVD (CHeCS, 2019).

Joining a health scheme provides farmers standardised guidelines and protocols for disease management, and allows them to work towards certification for their herd’s health status, helping improve their reputation and marketability (CHeCS, 2021). Farmers who are not already a member of a health scheme, but are already taking steps to control BVD in their herds, may be encouraged to join an accreditation scheme.

In England and Wales, the progress made by the neighbouring nations might also motivate farmers to test for BVD. Since 2015, all cattle entering Scotland from untested herds must be BVD-antigen tested within 40 days of arrival (Scottish Government, 2019). Therefore, producers in Scotland may be reluctant to buy from herds outside the scheme, or may ask sellers to individually test animals before purchase. Alternatively, animals that were born in a CHeCS-accredited herd, if the herd was accredited for the animal’s full lifetime, will be exempt from testing (Scottish Government, 2019).

To end with, the main barrier to achieving BVD eradication is the retention of PI cattle (Graham et al, 2021). Cattle born PI with BVD are highly likely to succumb to secondary diseases, experience reduced growth rates and have poorer survivability (Graham et al, 2015a).

If PIs are retained, a herd will remain BVD-positive and will potentially increase the likelihood of disease transmission in the region (Graham et al, 2015b). Therefore, it is essential that vets educate and engage farmers to remove PI animals, so that we can progress towards BVD eradication as quickly as possible, minimising the negative consequences that the disease has on the UK’s cattle health, welfare and productivity.

Eradication schemes are making progress to eradicate BVD from the UK; however, legislation is likely to be needed to completely eliminate the virus from the country.

In the absence of compulsory measures, the vet’s role remains key in actively engaging and guiding farmers to control BVD.