6 Mar 2023

Phil Elkins analyses how the Home Nations are clamping down on this disease, and what success they are having.

Image © danimages / Adobe Stock

Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) is an endemic disease in the cattle populations of much of the world.

The disease was first reported in 19461, with the first regional control programme launched in Lower Saxony, Germany2. Like most control programmes, this was voluntary and relied on funding from the farmers themselves.

Shortly after, compulsory BVD programmes were started in Scandinavian countries – driven initially by industry and then supported by legislation – leading to effective eradication of the disease from these countries. Despite the increasing knowledge of effective BVD control, an increasing range of vaccines available and a single land border with the Republic of Ireland, the UK is still working towards eradication.

BVD control is a devolved issue, with each of the four countries taking a different approach. This article will review the current status with BVD control schemes in each country, with some guidance on what may be coming in the future, and has been produced with kind support from the respective eradication bodies.

The Scottish BVD eradication scheme was the first to be set up, in 2010, with an initial voluntary screening approach.

Following the positive uptake of this scheme – indicating industry support for BVD eradication – phase two was initiated with mandatory herd screening for all breeding herds by February 2013, and annually thereafter. Phase three supplemented this with mandatory movement controls in 2014, including a ban on knowingly moving infected cattle, restrictions for untested herds and declaration of current status before sale.

Eighteen months later, phase four further refined the controls, with movement restrictions applied to all “not negative” herds and a reduction in the number of available testing options.

Phase five is the current phase of control and has been in place since December 2019. Further mechanisms in place are as follows:

Prior to the start of phase five, the Scottish Government published a report on the estimated savings to farmers of the scheme3. This showed a reduction of herd-level prevalence from 40% to 10%, with an estimated average saving of £2,000 to £14,000 per farm per year. Total eradication is estimated to benefit the industry by £2.4 million each year if it is achieved.

The PI locator is a publicly available tool that highlights the county, parish and holding number, and county/parish where PIs that have been retained on farm for more than 40 days are located.

At the time of writing, five holdings are on the list, showing great progress towards eradication. This has been facilitated greatly by the ScotMoves system, which replaced the British Cattle Movement System (BCMS) for Scotland in October 2021.

Northern Ireland’s industry-led BVD eradication programme is managed by Animal Health and Welfare NI (AHWNI). It has been compulsory since 1 March 2016 and includes the following provisions:

Due to the requirement to test all newborns, including abortions and stillbirths, the true prevalence of PIs can be known. No financial support is available, so to encourage the disposal of PI animals, the industry introduced a voluntary abattoir ban on the slaughter of BVD-positive animals and a non-conformance in the Farm Quality Assurance scheme when a PI is retained.

Since 2016, individual animal level prevalence has fallen by more than 50% and herd level prevalence has fallen by more than 60%.

More than 98% of the NI cattle population has a BVD-negative (direct or indirect) status (approximately 1.65 million animals).

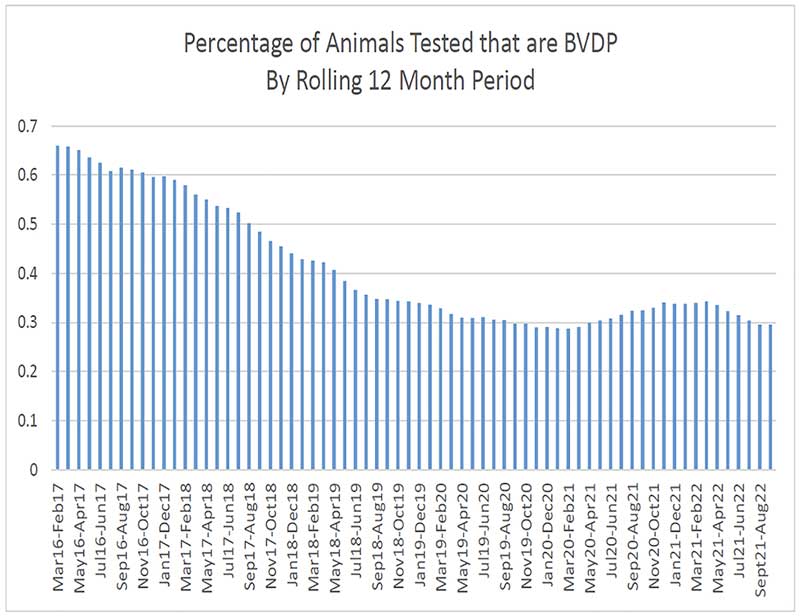

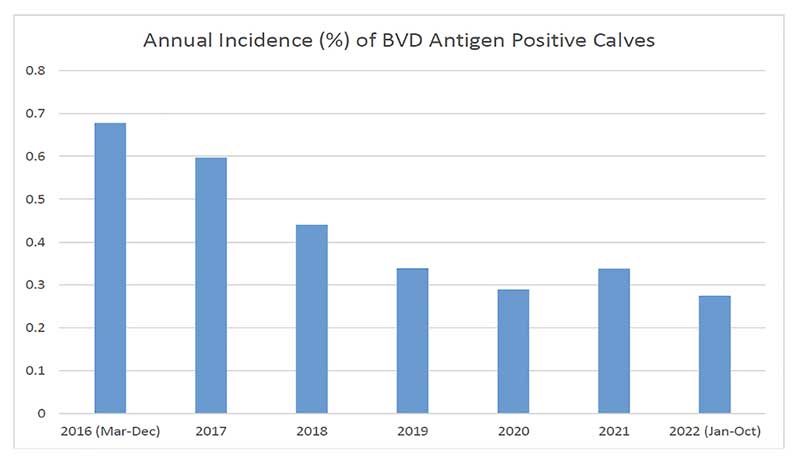

The animal level incidence of BVD increased during 2021 (Figures 1 and 2). Factors of concern were carryover of infection in breakdown herds, transmission of the virus to neighbouring farms, and farms purchasing from breakdown herds (primarily via transiently infected cattle and the Trojan horse effect).

The delay in progress has demonstrated the need for additional enforcement. As a result, DAERA has agreed to progress BVD herd restrictions in 2023 and the industry continues to make representations to DAERA regarding further work that is essential for the eradication of BVD.

Both the Scottish and Northern Irish schemes show how collaboration between industry and policy can lead to large strides being made in the journey towards eradication. Progressive standards, together with legislative support, will continue to drive success in these projects.

Gwaredu BVD in Wales has provided funding for BVD surveillance through a partnership between Coleg Sir Gâr and the RVC since 2017. Funding worth £10 million was awarded by the Welsh Government using EU funding.

The five years of funded surveillance has come to an end in December 2022, with three months remaining for claims and completion of paperwork.

The scheme is based around three key cornerstones:

The scheme was designed to support the relationship between local vet practices and individual farmers.

Out of approximately 11,000 Welsh cattle herds, 9,272 have had at least one surveillance test performed. This has revealed approximately 1,000 herds eligible for further funding to identify PIs, which has found around 1,000 PIs. Evidence from the first 300 PIs identified showed that 50% were retained on farm and 25% sold on. Only 25% of identified PIs were culled.

This work shows that a lot of education is still needed and further steps to be taken for Wales to progress towards eradication. The progression from the EU-funded phase of Gwaredu BVD is awaiting an announcement of support from the Welsh Government – which, at the time of writing, was “due imminently”. The hope is for progression to a mandatory scheme with legislative support to initially require roll-out of surveillance testing to all herds annually.

One of the delays has been the release of the new database to replace BCMS, which will allow centralisation of recording of herd BVD status.

Using the Scottish scheme as a comparison, it seems likely that Welsh eradication is at least 10 to 15 years away.

The BVDFree England scheme launched on 1 July 2016 with the support of more than 100 industry organisations. The BVDFree board provides governance for the scheme and consists of six industry partners (the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, NFU, BCVA, National Beef Association, Livestock Auctioneers’ Association and HolsteinUK), independent farmers and an APHA representative.

Between 2018-21, a Rural Development Programme for England-funded scheme called “Stamp it out” worked in partnership with BVDFree England. The £5.7 million project provided funding for 8,000 farms to conduct check testing (and further investigations of discovered PI animals) via their vets. This initiative allowed registered farmers to opt into signing up to the BVDFree England scheme and, consequently, led to an additional 4,576 holdings registered.

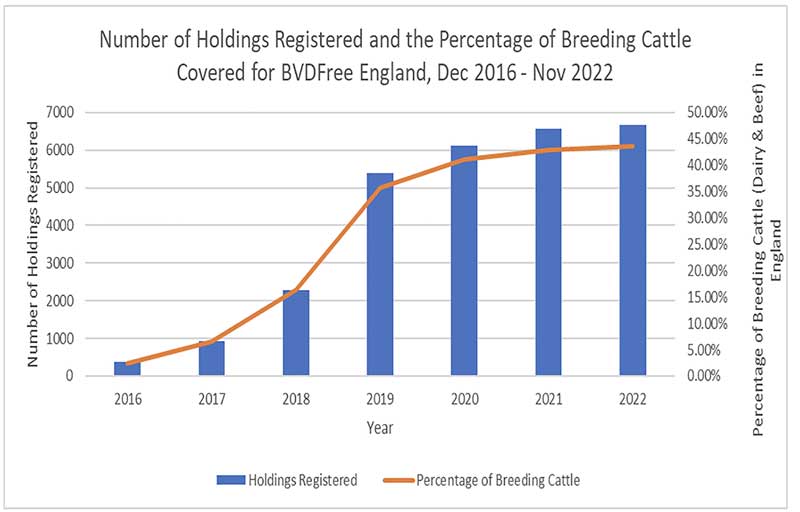

As of October 2022, 6,659 holdings were registered to BVDFree England, which has an estimated coverage of 44% of beef and dairy breeding cattle in England (Figure 3). This is a purely voluntary and farmer-funded scheme, with subsidies added to the cost of testing to cover the cost of registration.

The scheme also engages with:

Similar to Wales, the scheme needs to develop to expand coverage to the whole breeding herd, and also, to incorporate further restrictions to drive towards eradication.

In 2021, Defra introduced plans for the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway: each livestock sector will focus on a particular disease or syndrome.

The focus for English cattle was decided to be on eradication of BVD. Plans are set to launch a new voluntary BVD control scheme from late 2023 as announced by Defra; although, it is the author’s belief that legislation will be required to ensure full success of any scheme going forwards.

Taking evidence from other BVD eradication schemes, as well as those in place in the UK, voluntary schemes are difficult to manage and achieve sufficient uptake4.

In contrast, compulsory, and legislatively enforced schemes – especially when supported by appropriate methods of identification of elimination of disease – can lead to successful control of the disease.

The devolved nations are at different stages of their journey towards eradication, but the evidence is that the goals are getting closer to being achieved.