21 Sept 2021

Matt Yarnall, global technical manager for ruminant vaccines at Boehringer Ingelheim, presents findings from the latest National BVD Survey.

Image © goodluz / Adobe Stock

Farmers from all parts of the UK are reporting a positive impact on many areas of cattle health since embarking on bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) eradication programmes.

According to the National BVD Survey, which took place in January 2021 and attracted a record number of responses (1,236 farmers), engagement in schemes is up in all four devolved nations1.

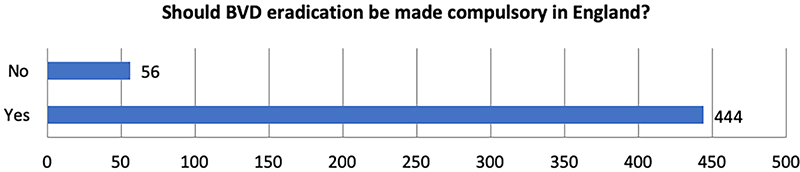

However, the differences in farmer behaviour in those where they are voluntary versus mandatory is significant. In fact, responses from farmers in England suggest strong support for a move towards a mandatory scheme (Figure 1).

Perhaps reflecting the advanced stage of the eradication programme in Scotland, or the addition of the phase five requirements in 2019 – whereby BVD-positive animals need to be housed separately – 36% of respondents said they used quarantine as a BVD biosecurity measure. This may seem low – however, the corresponding figure in Wales was 8%. In England, 7% of farmers said they had no biosecurity measures1. This figure is worrying, according to Lorna Gow, project lead for BVDFree England.

She has also noted that it can be difficult to balance focus across the different areas of control. Protecting a herd with a combination of biosecurity measures, vaccination, and ongoing and effective surveillance seems to be one of the hardest aspects of BVD eradication to get right. It may be general biosecurity measures aren’t considered specific for BVD, but undoubtedly, room for improvement exists here.

True biosecurity in most of the UK is hard to achieve – most farms have neighbouring cattle somewhere on the boundary; equally, calves or heifers might be reared away and then brought back. Add to that the issue of auction mart visits and bringing new animals on to the farm, and it’s easy to see how, in real life, the odd slip-up can occur.

Given the insidious nature of the disease, it’s simply not possible to know whether the virus is present on a farm without undertaking structured diagnostic testing. Even with ear tagging and regular surveillance, lapses can – and do – allow the virus in, where it can rapidly lead to reduced performance.

A study in 2020 looked at reduced performance in dairy herds exposed to BVD virus. The Advance study, the biggest European study of its kind, evaluated the impact of BVD in dairy herds using a treated and control group approach2.

To reflect a fairly common situation in UK herds, the study investigated the performance of cattle on commercial dairy farms that were endemically infected with BVD and not currently vaccinating.

Half the cattle were vaccinated with the live BVD vaccine Bovela to create a protected group that was then compared with the unprotected control group. Animals from a number of commercial farm settings from throughout Europe, including two from the UK, were studied and in total, records from 1,197 animals were analysed for a year, providing data from 1,559 separate lactations.

The study showed cattle in endemically infected herds that were not protected against BVD produced up to 1.8 litres less milk per day during early lactation, even in the absence of clinical signs of BVD infection2.

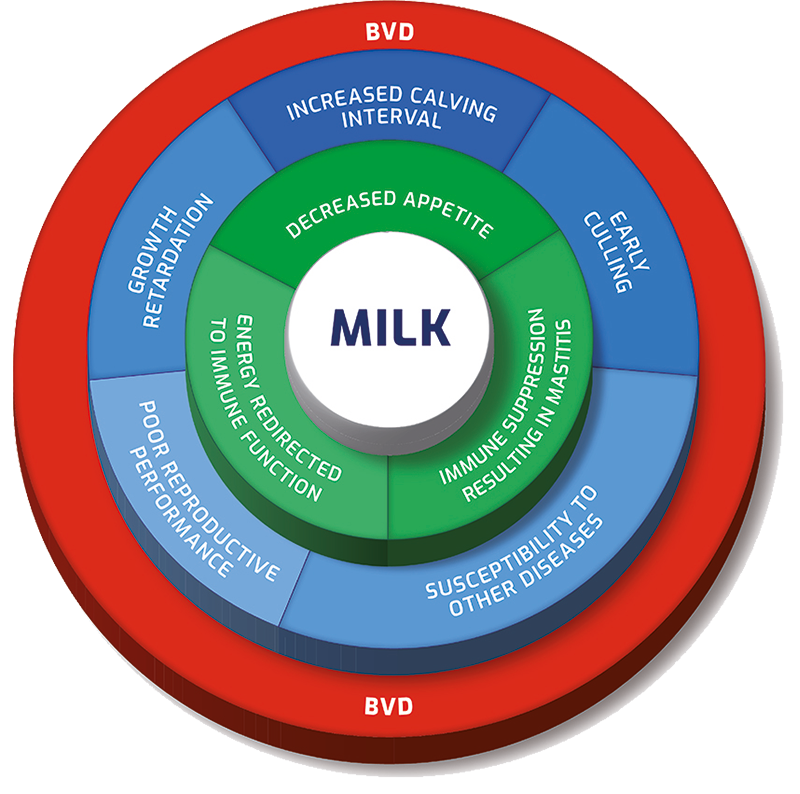

BVD infection impacts many aspects of cattle health and production, and its impact on fertility, early abortion and increasing the calving interval are well known3. BVD also affects growth, reduces appetite, suppresses the animal’s immune system and directs energy from the diet into fighting infection. Together, these add up to reduced milk production (Figure 2).

While the impact of a BVD outbreak in a naive herd is relatively well understood, this study found that failing to control BVD in already infected herds with no clinical evidence of disease could cost up to 169 litres of milk per animal, per lactation2.

In the study, the vaccinated cows produced more milk than the unvaccinated ones, and the economic benefit for the farmer – in terms of milk production – was up to £44 at 26 pence per litre, and no post-vaccination drop in milk production was seen.

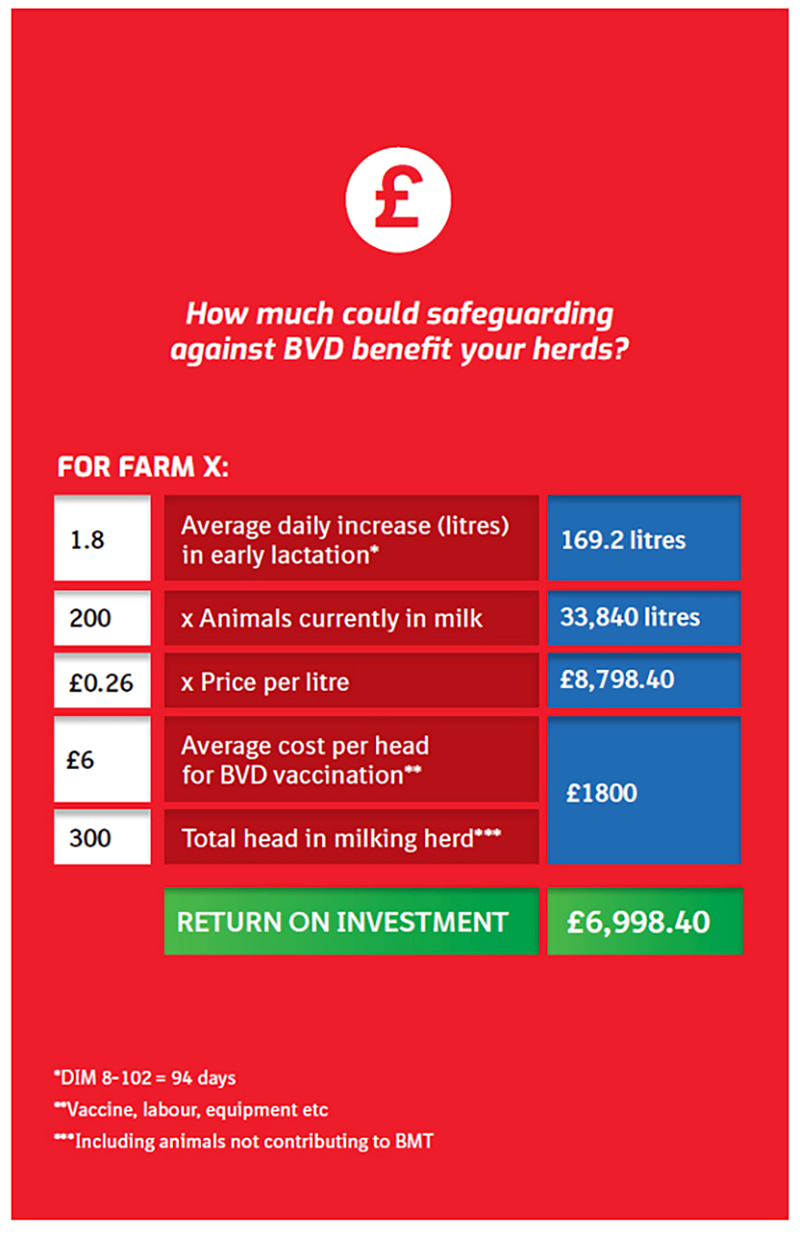

A cost calculator has been produced (Figure 3) showing potential return on investment for vaccinating a whole milking herd. Visit www.makebvdhistory.co.uk for full details. For a 200-cow milking herd selling milk at 26 pence per litre, the return on investment of opting to vaccinate could be £6,998.40.

Commenting on the findings, the study monitor and main author Ellen Schmitt-van de Leemput, who is based in France, said: “The Advance study has completely changed my appreciation of how BVD can impact a farm. I was shocked at the impact BVD has on milk production – this study shows that it’s not just farms with poor fertility as a result of BVD that would benefit from vaccination.”

The data highlights not only the importance of protecting a herd’s status once free of BVD, but also the consequences of endemic BVD on milk production, and clearly shows the economic benefit of eradicating BVD from a dairy herd.

Dr Schmitt-van de Leemput added: “However, as eradication progresses throughout all parts of the UK, and PI [persistently infected] animals are removed from the population, natural exposure reduces.

“The eventual result of this is that herds become naive and highly susceptible to infection. With decreasing natural immunity and the ever-present threat of infection, annual vaccination to achieve a high level of protection will protect these herds against the devastating effects of BVD outbreaks4,5.”

This impact has been seen in Ireland and Germany, where continued flare-ups of PIs have extended the tail of their eradication programmes.

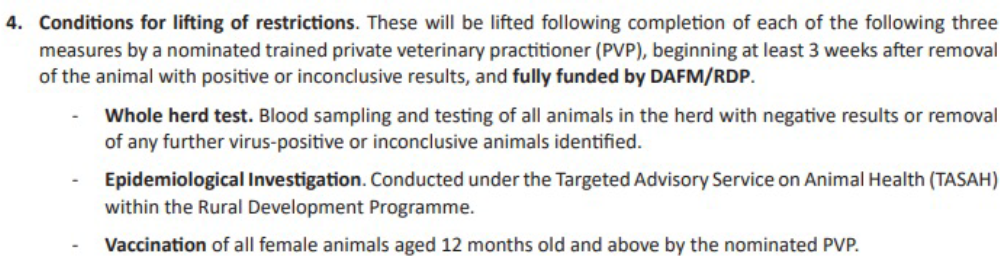

Current requirements in Ireland are designed to stamp out the disease in time to declare freedom from BVD in 2023, with stringent measures intended to maximise the chance of success in the final stages.

Any herd that receives a positive or inconclusive ear tag test will need to remove the animal immediately, as well as perform a raft of measures, including compulsory vaccination6 (Figure 4).

As other countries seek to catch up with Ireland’s advanced programme, vets will need to better communicate to their farmers the impact of the disease, highlighted by the Advance study, and the cost of not eradicating it, as well as changing their mindset on effective biosecurity and vaccination.