1 Apr 2025

Anna Bruguera Sala DVM, MVM, MRCVS discusses this viral disease, the control programmes for it and the long journey towards its eventual elimination in each home nation.

Image: nickalbi / Adobe Stock

The negative impacts that bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) has on cattle health, welfare, and herd productivity and economics (Bruguera Sala, 2024) have led many countries to implement eradication programmes to eliminate the disease from their national herd.

The Scandinavian countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland) started control programmes in the early 1990s and achieved freedom from the disease in about 10 years (Moennig and Becher, 2015).

In the UK, Scotland was the first nation to implement a nationwide BVD eradication scheme (Scottish Government, 2023). Northern Ireland followed suit in 2013 and Wales started their mandatory scheme in 2024, leaving England as the only UK nation where BVD control is still voluntary.

This article reviews the latest efforts and progress made by each UK nation in the fight against the virus.

The Scottish BVD Eradication Scheme started in September 2010 with an initial voluntary phase of subsidised testing, which lasted until April 2011 (phase one; Scottish Government, 2023). The scheme primarily relies on serological screening of cattle herds, through youngstock antibody check tests, although individual antigen (virus) testing of newborn calves or whole-herd testing are also accepted screening methods.

Annual testing of all breeding herds became compulsory in February 2013 (phase two), followed by the introduction of the first mandatory control measures and movement restrictions for not-negative herds in January 2014, with the start of the third phase (Scottish Government, 2023). These restrictions were further strengthened in June 2015 with the launch of phase four. The Scottish scheme is now in its fifth stage, which began in December 2019 (Scottish Government, 2019).

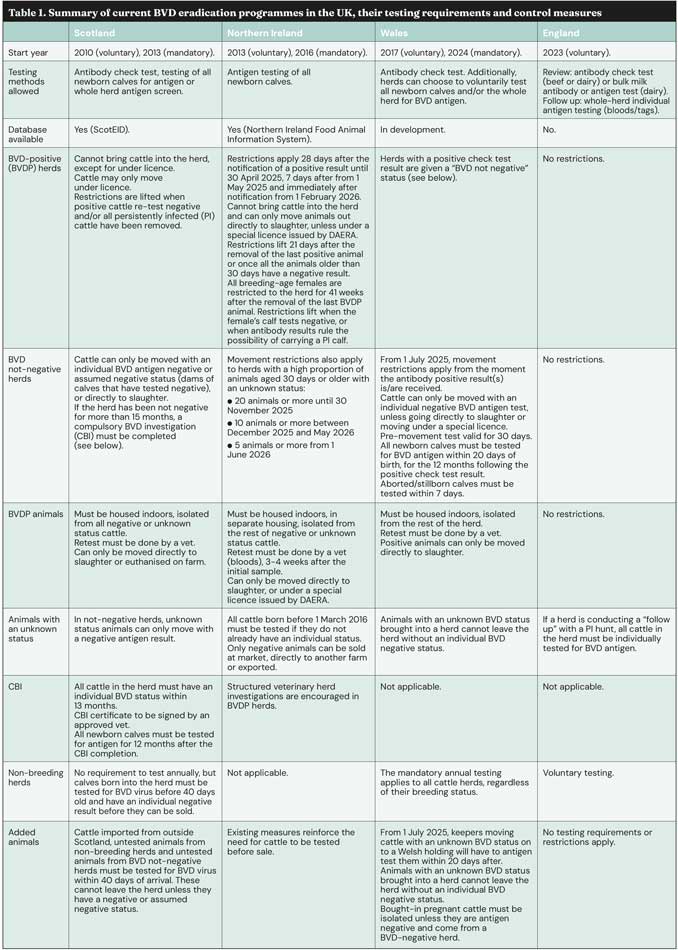

Table 1 summarises the current BVD control measures that apply in each UK nation.

In November 2023, the Scottish Government launched a consultation on the potential introduction of phase six, which, if implemented, could further tighten restrictions on not-negative herds, modify testing requirements, and shorten the timeframe for completing a compulsory BVD investigation (CBI), which are required for herds that have remained not-negative for more than 15 months (Scottish Government, 2019).

At the end of the voluntary phase in 2011, an estimated 30% of tested herds had positive BVD antibody results (Scottish Government, 2015a). By 2015, this figure had declined to 15% (Scottish Government, 2015b). Since then, the scheme has continued to make progress, with the prevalence of not-negative herds decreasing year on year.

However, in recent years, the decline has slowed. As of December 2024, 92.9% of Scottish herds were negative, a slight increase from 92.4% negative herds in December 2023. The proportion of not-negative herds has also decreased marginally, from 7.4% in 2023 to 7.0% in 2024, while the percentage of BVD-positive (BVDP) herds has remained stable at 0.1% (EPIC Scotland, 2025; EPIC Scotland, 2024). According to the ScotEID BVD PI Locations database, as of early February 2025, only two herds were retaining persistently infected (PI) cattle (ScotEID, 2025).

Scotland is close to achieving BVD eradication. The introduction of Phase 6 could accelerate the scheme’s progress and get Scotland closer to its BVD-free goal.

The Northern Ireland BVD Eradication Programme also started with a voluntary phase in January 2013 (Strain et al, 2021). The programme became compulsory in March 2016 with the introduction of The Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Eradication Scheme Order (Northern Ireland) 2016.

The Northern Ireland (NI) programme follows a similar structure to the Republic of Ireland’s programme (Graham et al, 2021) and is based on the individual testing of newborn calves for BVD antigens.

Since 2016, all newborn, stillborn and aborted calves or fetuses, as well as those that die before tagging, must be tested within 20 days of birth. Animals that test positive are assigned a BVDP status and can only be moved directly to slaughter.

In 2022, the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in NI held a public consultation on the introduction of additional control measures (DAERA, 2022). This led to the creation of The Bovine Viral Diarrhoea Control Order (Northern Ireland) 2024 which, from 1 February 2025, introduced the first movement restrictions for herds with BVDP or inconclusive results. The restrictions are summarised in Table 1.

The new control measures also include restrictions on herds with animals with unknown status, and breeding females in restricted herds. Additionally, all cattle born before 1 March 2016 must now be tested if they do not already have an individual BVD status.

To help producers adjust to the new regulations, a “grace period” has been provided for certain measures, but this will be progressively shortened. From 1 February 2026, restrictions will take effect immediately on notification of a positive result.

At the end of the first year of the compulsory NI programme, 11% of tested herds had at least one BVDP result. At the animal level, 0.59% were confirmed as PI (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2017). In the year leading up to 31 October 2024, the herd-level prevalence (herds with an initial positive or inconclusive result) had dropped to 2.44%, meaning 97.56% of herds had a negative status.

At the animal level, 0.205% had a BVDP or inconclusive result in October 2024 (Animal Health and Welfare NI, 2025). As of January 2025, BVDP cattle had still been identified in all six NI counties (Animal Health and Welfare NI and DAERA, 2024).

With the implementation of the new compulsory control measures, it is hoped that NI will make significant progress toward the eradication of BVD.

The journey to BVD eradication in Wales also started with a voluntary and subsidised programme, Gwaredu BVD, which was launched by the Welsh Government in May 2017 (Animal Health and Welfare Wales, 2023). The scheme offered funding for a veterinary visit and antibody check test, with additional funding available if a PI hunt was required. The voluntary programme ran until December 2022 and covered 85% of Welsh herds. The percentage of herds with positive check tests declined from 27% in 2018 to 23% in 2022 (Animal Health and Welfare Wales, 2023).

In June 2022, the Welsh Government also opened a consultation on the potential introduction of a compulsory scheme (Welsh Government, 2022). The industry’s responses were widely positive and led to the launch of the new mandatory Welsh BVD eradication scheme in 2024, covered in the Welsh law by The Bovine Viral Diarrhoea (Wales) Order 2024.

The new scheme in Wales follows a very similar structure to the Scottish scheme. From 1 July 2025, many of the requirements and movement restrictions that apply in Scotland will also apply in Wales (see Table 1 for a comparison of all UK nations’ schemes). However, from its start, the Welsh scheme has been more restrictive in the number of testing options allowed, and movement restrictions will also apply much sooner than in Scotland and NI, just a year after the introduction of the scheme (1 July 2026). It is expected that the stricter measures will encourage faster removal of PI cattle from Welsh herds, and this could lead to Wales seeing a faster decline in BVD prevalence than in Scotland.

England is currently the only UK nation without a compulsory BVD eradication scheme. BVDFree England, the voluntary industry-led initiative launched in 2016, closed in July 2024 following the introduction of the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway (AHWP; AHDB, 2025; Defra and RPA, 2025a).

In 2023, the AHWP introduced a new phase of subsidised BVD testing, providing funding until June 2027. Through this scheme, producers can apply for three annual “reviews” and “endemic disease follow ups” to monitor and control BVD in their herds.

As part of a review, cattle herds receive funding for a veterinary visit and either an antibody check test or bulk milk test. If a positive result is found, a PI hunt can be conducted under the “endemic disease follow up”. Since January 2025, PI hunts are also available to dairy herds and herds with a negative review, if the veterinarian suspects BVD may still be present (Defra and RPA, 2025b).

Figures published following the closure of BVDFree England show that the voluntary scheme engaged 45% of holdings, but only 28% of those had a test-negative herd status (AHDB, 2025). While this indicates good uptake, many herds remained with an unknown or positive status. The AHWP funding provides an opportunity to improve engagement with BVD surveillance and control.

Until February 2025, a potential limitation to increasing engagement in BVD monitoring was that farms with more than one species could only apply for funding for one. Therefore, farms that had cattle and sheep might have opted to carry out a flock review, because the endemic disease follow up for sheep offers the option to test for wider range of conditions (Defra and RPA, 2025c).

This could have reduced the number of cattle herds that tested for BVD, but since 26 February 2025, livestock farmers can apply for funding for more than one species (Defra, 2025), removing this limitation. The AHWP could serve as a stepping stone towards the introduction of mandatory BVD eradication measures in England, following the path of Scotland, NI and Wales. Encouraging producers to engage with the AHWP now could help them prepare for any future regulations.

Additionally, as other UK nations tighten their control measures, English cattle may be seen as a higher biosecurity risk, potentially limiting trade opportunities for producers selling into Scotland or Wales.

While the AHWP provides a clear benefit to cattle producers to help them control BVD in their herds, its voluntary nature means participation is not guaranteed. Without widespread engagement, England will fall behind in BVD eradication, affecting both cattle health and trade.

A structured transition to compulsory measures will be necessary to ensure long-term progress towards BVD eradication in England.

BVD eradication is an achievable goal, and the progress made across the UK demonstrates that a structured approach can significantly reduce disease prevalence.

Eliminating BVD would bring substantial benefits to the cattle industry, improving animal health, welfare, efficiency and productivity.

Scotland has led the way with its long-standing scheme, followed by Northern Ireland and now Wales.

England risks falling behind; however, the government-led and subsidised AHWP offers hope that compulsory measures may soon follow, bringing the UK closer to eliminating BVD.