31 Dec 2019

Caring for the newborn calf

Nicola Gladden discusses the importance of good postpartum care, including the use of analgesia and provision of colostrum.

Figure 1. Cows should calve down in a clean environment. Image: Kathryn Ellis.

Calving can be a challenging time for both the cow and calf.

Good neonatal care of the calf can prevent problems occurring and establish a foundation of good health that will have a long-lasting beneficial effect on the calf.

Parturition

Animals should be housed in a dry, clean environment for calving, which may be either in a group pen or individual calving pens (Figure 1).

If animals are moved in the immediate pre-calving period, it is important movement is timed appropriately to avoid inadvertently increasing the likelihood of dystocia1.

Dystocia is well known to be associated with a higher risk of stillbirth in cattle and is associated with a poorer chance of survival in calves that are not stillborn2-10.

A well-managed calving can, therefore, greatly assist the calf in its first few days to weeks of life, compared to a poorly or inappropriately managed calving, which may result in the death of the calf or the delivery of a calf that lacks the vigour required for survival.

Assessment of neonatal calf vigour

In babies, newborn vigour is assessed using a scoring system developed more than 60 years ago by Virginia Apgar; this system is now referred to as the APGAR (Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respiration) score11,12.

APGAR scoring has been adapted for use in veterinary species, and assesses heart rate, respiratory effort, reflexes, motility and mucous membrane colour. Lower scores are associated with poorer vigour13-18.

This scoring system is simple and does not require specialised equipment; however, in a busy farm situation it can be time-consuming and laborious for a farmer to assess and score five different parameters for every calf born.

Work in beef calves has demonstrated assessment of the suckle reflex – in combination with the degree of calving difficulty experienced by newborn calves – is a simple, quick and effective tool to assess newborn calf vitality that may be more suited to use in a commercial farm environment19.

Assessment of vigour using this tool can then be used to determine how the calf should be managed in the postpartum period to optimise the potential for a healthy start to life.

Immediate postpartum care

In the immediate postpartum period, some calves are vigorous and need little assistance; however, all calves should be placed into sternal recumbency to facilitate ventilation20.

Some calves will require stimulation to breathe. In the past, it was common to place the calf over a gate, with the head down, in an attempt to clear the airway and stimulate breathing. This technique is no longer recommended and farmers should be advised to avoid doing this when dealing with a low-vigour calf.

Placing the calf in this position is counterproductive as it results in cranial movement of abdominal viscera due to gravity; this causes pressure on the thorax and reduces the ability of the lungs to inflate, making breathing more difficult for the calf.

If the head needs to be positioned downwards to facilitate draining of fluid from the airways, the calf can be placed in sternal recumbency on a bale and the head positioned down from here, although this is seldom necessary.

Mechanical ventilation can be performed by passing an endotracheal tube, or using a mask with an inflating bag, to provide positive pressure ventilation; however, this is not always possible in an on-farm situation.

Analgesia

Limited data is available regarding the use of analgesia in neonates.

Given the limited evidence available, it would be prudent to provide analgesia to newborn calves, especially if assistance was required or injury is suspected.

No analgesics are licensed in the UK for newborn calves – the provision of analgesia is, therefore, off-licence and statutory withdrawal periods should be applied.

Provision of colostrum

Calves are born almost agammaglobulinaemic and the importance of providing an adequate volume of good-quality colostrum within an appropriate time period postpartum has been recognised for a number of years25-28.

It has been demonstrated that calves fed their initial feed of colostrum more than four hours after birth are more likely to have failure of passive transfer than calves fed colostrum before they are four hours old29,30; therefore, it is important calves receive colostrum within the first four hours of life.

The volume of colostrum required by a newborn calf has traditionally been considered to be 10% of birthweight, estimated to be between 4 litres and 4.5 litres for a Holstein calf.

Work from Ireland has suggested a volume of colostrum equivalent to 8.5% of birthweight may be more appropriate31.

Colostrum cleanliness is of high importance, and colostrum should be harvested and stored in a hygienic manner that prevents contamination. Buckets containing colostrum should be covered (Figure 2) and colostrum that is not going to be used promptly should be refrigerated or frozen as soon as possible32,33.

Colostrum quality should be tested at each collection. An Ig concentration of 50mg/ml and greater is considered to be adequate34; colostrum with a concentration lower than this should not be fed to newborn calves.

Colostrum quality varies between breeds (Channel Island breeds tend to have higher quality colostrum than Holsteins), as well as between ages of cattle, with primiparous animals tending to have reduced colostrum quality compared to multiparous animals.

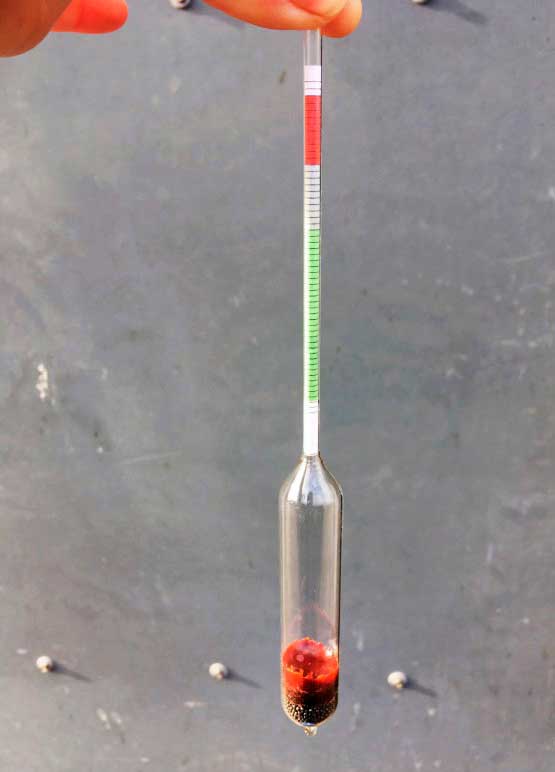

Colostrum quality can be easily and cheaply measured on farm either by using a colostrometer (Figure 3) or Brix refractometer.

A colostrometer is a glass weight that is placed in a cylinder containing the colostrum to be measured. If the colostrum is of a high quality – and, therefore, more dense – the colostrometer will float in the colostrum.

If the colostrum is of poor quality – less dense – the colostrometer will sink to the bottom of the cylinder.

Colostrometers have green and red marks on them to indicate whether the colostrum is of good quality (the green mark will be exposed, indicating the Ig concentration is more than 50mg/ml) or poor quality (the green mark will be submerged in colostrum and only the red mark will be exposed, indicating the Ig quality is less than 20mg/ml).

To use a Brix refractometer to measure colostrum quality, a drop of colostrum is placed on the refractometer and a record is taken from the Brix scale that can be seen through the eyepiece. Good-quality colostrum should measure 22% or greater on the Brix scale; this is equivalent to an Ig concentration of 50mg/ml.

Additional postpartum care

All calves should have the umbilicus treated to encourage the umbilical stump to heal as quickly as possible and to minimise the risk of bacterial infiltration of the umbilicus.

Iodine is commonly used, either as a dip or a spray; however, additionally to iodine, a number of other products are available.

If iodine is used, it is important it is not too concentrated; concentrations greater than 7.5% are caustic and can cause tissue damage to the umbilicus.

Whichever product is chosen, careful application to ensure adequate coverage of the umbilicus is important (Figure 4).

Timing of removal of the calf from the dam can be controversial; however, if the farm has problems with diseases – such as Johne’s disease – the sooner the calf is removed from the high-risk environment (the calving pen), the lower the risk of being infected.

Conclusion

While many calves that are born encounter few problems, a number of measures can be taken to optimise newborn calf health and survival in all calves.

Many of the measures and studies discussed in this article reference dairy herds; however, it is important to remember beef calves can also benefit from appropriate care in the neonatal period.

All calves benefit from adequate colostrum management and umbilical care at birth.

Optimisation of neonatal calf management can have far-reaching effects beyond the immediate postpartum period, and have beneficial effects on the health, welfare and productivity of the whole herd.

This article was reviewed by Katherine Ellis, BVMS, CertCHP, PhD, DipECBHM, MRCVS.

References

- Mee JF (2004). Managing the dairy cow at calving time, Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 20(3): 521-546.

- Lombard JE, Garry FB, Tomlinson SM and Garber LP (2007). Impacts of dystocia on health and survival of dairy calves, J Dairy Sci 90(4): 1,751-1,760.

- Patterson DJ, Bellows RA, Burfening PJ and Carr JB (1987). Occurrence of neonatal and postnatal mortality in range beef cattle. I. Calf loss incidence from birth to weaning, backward and breech presentations and effects of calf loss on subsequent pregnancy rate of dams, Theriogenology 28(5): 557-571.

- Laster DB and Gregory KE (1973). Factors influencing peri- and early postnatal calf mortality, J Anim Sci 37(5): 1,092-1,097.

- Arthur PF, Archer JA and Melville GJ (2000). Factors influencing dystocia and prediction of dystocia in Angus heifers selected for yearling growth rate, Aust J Agric Res 51(1): 147-154.

- Tenhagen BA, Helmbold A and Heuwieser W (2007). Effect of various degrees of dystocia in dairy cattle on calf viability, milk production, fertility and culling. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med 54(2): 98-102.

- Barrier AC, Haskell MJ, Birch S, Bagnall A, Bell DJ, Dickinson J, Macrae AI and Dwyer CM (2013). The impact of dystocia on dairy calf health, welfare, performance and survival, Vet J 195(1): 86-90.

- Hossein-Zadeh NG (2014). Effect of dystocia on the productive performance and calf stillbirth in Iranian Holsteins, J Agric Sci Tech 16: 69-78.

- Gundelach Y, Essmeyer K, Teltscher MK and Hoedemaker M (2009). Risk factors for perinatal mortality in dairy cattle: cow and foetal factors, calving process, Theriogenology 71(6): 901-909.

- Berger PJ, Cubas AC, Koehler KJ and Healey MH (1992). Factors affecting dystocia and early calf mortality in Angus cows and heifers, J Anim Sci 70(6): 1,775-1,786.

- Apgar V (1953). A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant, Curr Res Anesth Analg 32(4): 260-267.

- Finster M and Wood M (2005). The Apgar score has survived the test of time, Anesthesiology 102(4): 855-857.

- Veronesi MC, Panzani S, Faustini M and Rota A (2009). An Apgar scoring system for routine assessment of newborn puppy viability and short-term survival prognosis, Theriogenology 72(3): 401-407.

- Vannucchi CI, Rodrigues JA, Silva LC, Lúcio CF and Veiga GA (2015). Effect of dystocia and treatment with oxytocin on neonatal calf vitality and acid-base, electrolyte and haematological status, Vet J 203(2): 228-232.

- Murray CF and Leslie KE (2013). Newborn calf vitality: risk factors, characteristics, assessment, resulting outcomes and strategies for improvement, Vet J 198(2): 322-328.

- Doebeli A, Michel E, Bettschart R, Hartnack S and Reichler IM (2013). Apgar score after induction of anesthesia for canine cesarean section with alfaxalone versus propofol, Theriogenology 80(8): 850-854.

- Veronesi MC, Riccaboni P, Faustini M, Battocchio M, Cairoli F and Villani M (2005). Potential association between placental features and Apgar scores after normal parturition in the Thoroughbred horse, J Anim Vet Adv 4(12): 965-970.

- Murray CF (2014). Characteristics, risk factors and management programs for vitality of newborn dairy calves, PhD thesis, University of Guelph.

- Homerosky ER, Timsit E, Pajor EA, Kastelic J and Windeyer MC (2017). Predictors and impacts of colostrum consumption by 4h after birth in newborn beef calves, Vet J 228: 1-6.

- Nagy DW (2009). Resuscitation and critical care of neonatal calves, Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 25(1): 1-11.

- Gladden N, McKeegan D, Viora L and Ellis KA (2018). Postpartum ketoprofen treatment does not alter stress biomarkers in cows and calves experiencing assisted and unassisted parturition: a randomised controlled trial, Vet Rec 183(13): 414.

- Pearson JM, Pajor E, Campbell J, Levy M, Caulkett N and Windeyer MC (2019). A randomised controlled trial investigating the effects of administering a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug to beef calves assisted at birth and risk factors associated with passive immunity, health, and growth, Vet Rec Open 6(1): e000364.

- Pearson JM, Pajor EA, Campbell JR, Caulkett NA, Levy M, Dorin C and Windeyer MC (2019). Clinical impacts of administering a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug to beef calves after assisted calving on pain and inflammation, passive immunity, health, and growth, J Anim Sci 97(5): 1,996-2,008.

- Gladden N, Ellis K, Martin J, Viora L and McKeegan D (2019). A single dose of ketoprofen in the immediate postpartum period has the potential to improve dairy calf welfare in the first 48h of life, Appl Anim Behav Sci 212: 19-29.

- Weaver DM, Tyler JW, VanMetre DC, Hostetler DE and Barrington GM (2000). Passive transfer of colostral immunoglobulins in calves, J Vet Intern Med 14(6): 569-577.

- McGuire TC, Pfeiffer NE, Weikell JM and Bartsch RC (1976). Failure of colostral immunoglobulin transfer in calves dying from infectious disease, J Am Vet Med Assoc 169(7): 713-718.

- Besser TE, Szenci O and Gay CC (1990). Decreased colostral immunoglobulin absorption in calves with postnatal respiratory acidosis, J Am Vet Med Assoc 196(8): 1,239-1,243.

- Godden S (2008). Colostrum management for dairy calves, Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract 24(1): 19-39.

- Chigerwe M, Tyler JW, Schultz LG, Middleton JR, Steevens BJ and Spain JN (2008). Effect of colostrum administration by use of oroesophageal intubation on serum IgG concentrations in Holstein bull calves, Am J Vet Res 69(9): 1,158-1,163.

- Beam AL, Lombard JE, Kopral CA, Garber LP, Winter AL, Hicks JA and Schlater JL (2009). Prevalence of failure of passive transfer of immunity in newborn heifer calves and associated management practices on US dairy operations, J Dairy Sci 92(8): 3,973-3,980.

- Conneely M, Berry DP, Murphy JP, Lorenz I, Doherty ML and Kennedy E (2014). Effect of feeding colostrum at different volumes and subsequent number of transition milk feeds on the serum Immunoglobulin G concentration and health status of dairy calves, J Dairy Sci 97(11): 6,991-7,000.

- Stewart S, Godden S, Bey R, Rapnicki P, Fetrow J, Farnsworth R, Scanlon M, Arnold Y, Clow L, Mueller K and Ferrouillet C (2005). Preventing bacterial contamination and proliferation during the harvest, storage, and feeding of fresh bovine colostrum, J Dairy Sci 88(7): 2,571-2,758.

- Denholm KS, Hunnam JC, Cuttance EL and McDougall S (2017). Influence of preservation methods on the quality of colostrum sourced from New Zealand dairy farms, NZ Vet J 65(5): 264-269.

- Denholm KS, Hunnam JC, Cuttance EL and McDougall S (2017). Associations between management practices and colostrum quality on New Zealand dairy farms, NZ Vet J 65(5): 257-263.

- Flower FC and Weary DM (2001). Effects of early separation on the dairy cow and calf, Appl Anim Behav Sci 70(4): 275-284.

- Meagher RK, Beaver A, Weary DM and von Keyserlingk MAG (2019). Invited review: a systematic review of the effects of prolonged cow–calf contact on behavior, welfare, and productivity, J Dairy Sci 102(7): 5,765-5,783.

- Ventura B, von Keyserlingk MA, Schuppli C and Weary D (2013). Views on contentious practices in dairy farming: the case of early cow-calf separation, J Dairy Sci 96(9): 6,105-6,116.

- Beaver A, Meagher RK, von Keyserlingk MAG and Weary DM (2019). Invited review: a systematic review of the effects of early separation on dairy cow and calf health, J Dairy Sci 102(7): 5,784-5,810.

Meet the authors

Nicola Gladden

Job Title