19 Dec 2016

Oliver Tilling explains the importance of a calf's first nutritional intake and steps for its effective production and management.

Figure 2. A newborn calf.

The most important meal in a calf’s life is its first – that of colostrum, the first thick, yellow milk a cow or heifer produces after calving (Figure 1).

The importance of ensuring a calf receives adequate colostrum cannot be overemphasised. Calves that do have a reduced risk for pre-weaning morbidity and mortality, plus additional long-term benefits of:

The main characteristics of colostrum are:

Colostrum is very different to milk (Table 1), being nearly twice as concentrated (23.9% versus 12.5%). Much higher levels of fat are found in colostrum compared to milk, and much higher levels of protein – especially immunoglobulins (67 times greater in colostrum versus milk).

| Table 1. Characteristics and composition of Holstein colostrum and milk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colostrum | ||||

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | Milk |

| Total solids (%) | 23.9 | 17.9 | 14.1 | 12.5 |

| Fat (%) | 6.7 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| Solids-non-fat (5) | 16.7 | 12.2 | 9.8 | 8.6 |

| Total protein (%) Casein (%) Albumin (%) Immunoglobulins (antibodies)(%) |

14 4.8 0.9 6 |

8.4 4.3 1.1 4.2 |

5.1 3.8 0.9 2.4 |

3.2 2.5 0.5 0.09 |

| Lactose (%) | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.9 |

| Calcium (%) | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Vitamin A (μg/100ml) | 295 | 190 | 113 | 0.13 |

| Vitamin E (μg/g fat) | 84 | 76 | 56 | 15 |

| Vitamin B12 (μg/100ml) | 1.9 | – | 2.5 | 0.6 |

In late pregnancy, a cow concentrates immunoglobulins in her colostrum, so her calf receives immediate, preformed immunity to many of the diseases to which it will be exposed. The final concentration of immunoglobulins in colostrum is much higher than those originally present in the blood, and is the reason why the protein content of colostrum is so high.

Cow and calf blood supplies are separated by the placenta in the uterus. This prevents transmission of immunoglobulins. The calf, therefore, depends almost entirely on absorption of immunoglobulins from colostrum after birth1 (Figure 2). Absorption of immunoglobulins across the calf’s small intestine during the first 24 hours after birth is called passive transfer, and helps protect the calf against disease until its own immature immune system becomes functional.

The immunity given to the calf is only related to the infections the cow herself has contacted. If a cow is purchased and moved into a new herd only a few days before calving then a risk exists that the calf will be challenged by infections for which it has no colostral protection2. So cows and heifers should be on the farm at least three weeks prior to calving.

Failure of passive transfer of immunity (FPT) occurs when a calf fails to absorb an adequate quantity of antibodies4. FPT is not a disease, but a condition that predisposes the newborn calf to the development of disease5. The estimated prevalence of FPT in US dairy heifers is 19.2%4, with 31% of deaths in the first three weeks due to FPT6.

A study in south-west England (unpublished data) found 34% of dairy calves had FPT; in other words, one in three calves had not received adequate colostrum.

Effective colostrum management is the cornerstone of a good heifer rearing programme. When it comes to colostrum management, the focus must be on five “Q” key areas7:

When advising a farm client on effective colostrum management, the clinician must understand the justification for his or her advice around each of the five key areas7. The aims are to feed only high-quality colostrum that has been measured using a colostrometer or Brix refractometer. A volume of mother’s colostrum that equals to 10% to 12% of a calf’s bodyweight should be fed within four hours of birth and a further two litres within 12 hours of birth. Finally, colostrum should be collected and stored in a hygienic way.

Before making any changes to colostrum management, objective data is needed on the situation. Furthermore, it is no good putting new colostrum management practices in place if we are unable to monitor progress. This focuses on measuring passive transfer. Several laboratory tests exist for measuring passive transfer – serum total protein by refractometer is the most reliable test for herd screening5. It is a simple, rapid and inexpensive tool. All farm veterinary practices should have the necessary equipment for this.

A serum total protein concentration of 5.2g/dL is equivalent to an IgG concentration of 1,000mg/dL. On a healthy, adequately hydrated calf, a serum total protein of 5.2g/dL or greater is associated with adequate passive transfer.

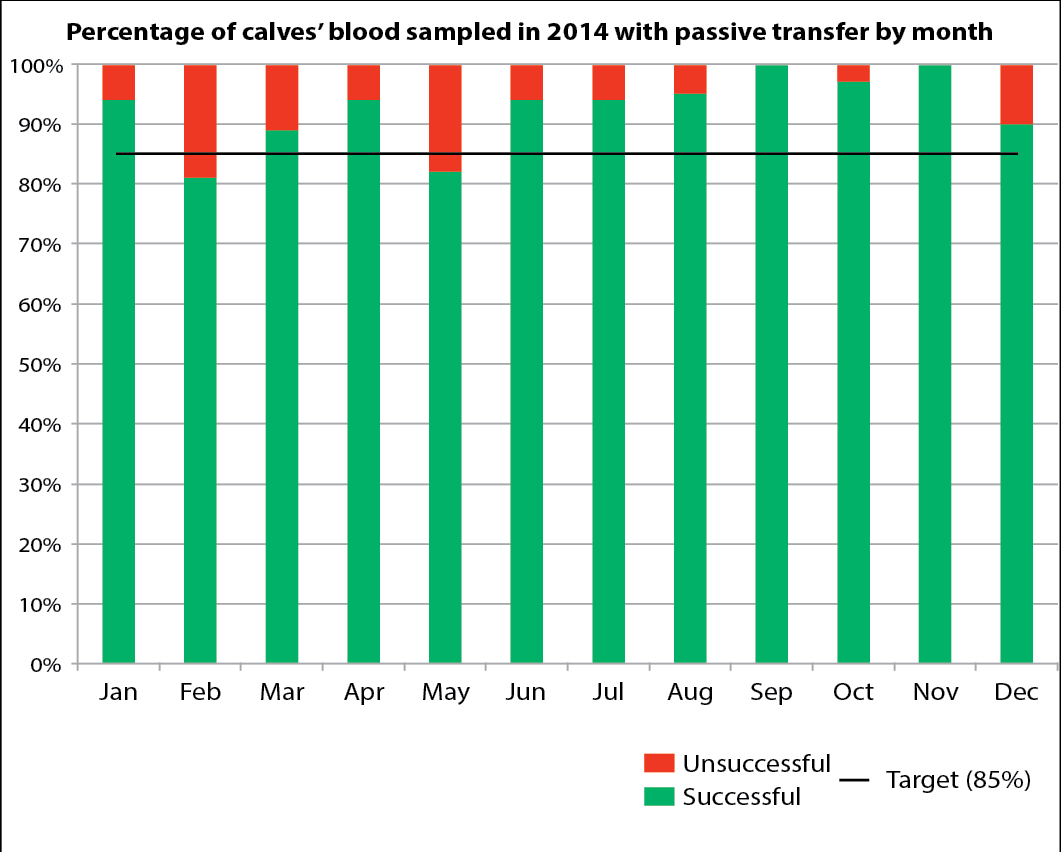

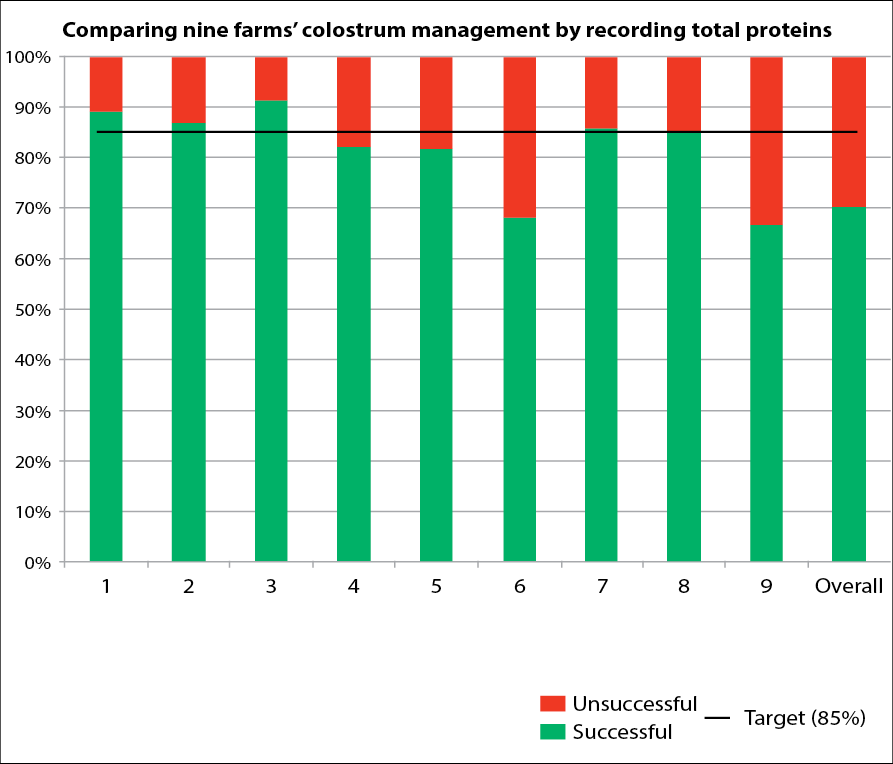

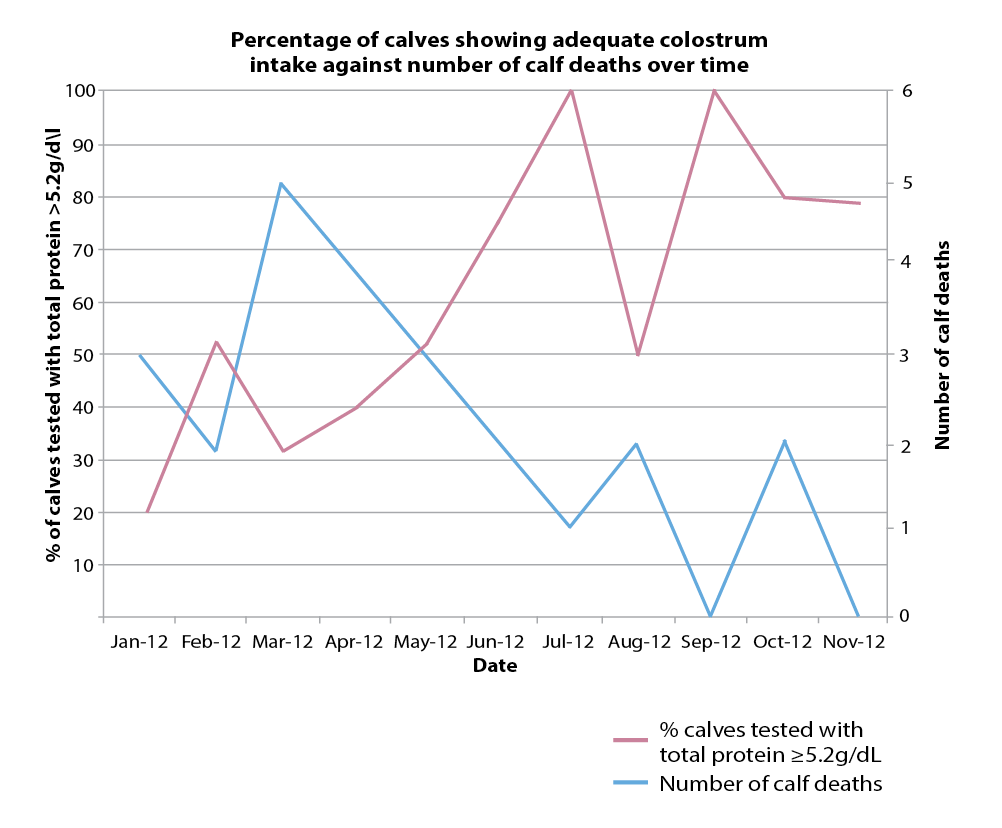

Regular monitoring of colostrum management by blood sampling calves enables longer-term patterns to be built up (Figure 3). A target of greater than or equal to 85% of all calves sampled having a result of greater than or equal to 5.2g/dL is readily achievable. Monitoring also allows benchmarking between farms (Figure 4), as well as comparing disease levels with total protein levels (Figure 5).

A strong association between FPT and the routine measurement of serum total protein in heifer calves has been observed. The odds of FPT are nearly 14 times higher on farms that do not routinely monitor total proteins to assess passive transfer compared to those that do4. It is logical improving colostrum management and, ultimately, reducing FPT is a focus of farms that routinely evaluates the passive transfer status of their calves.

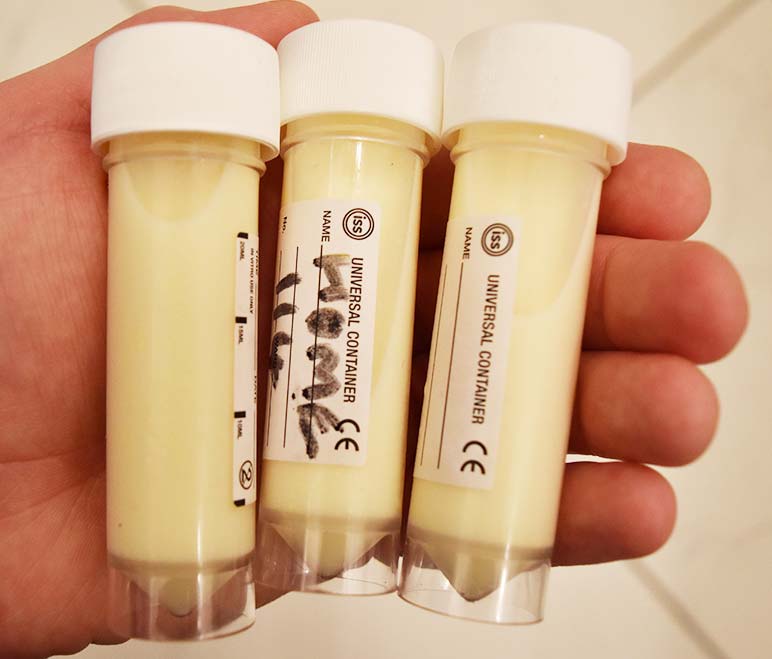

Colostrum cleanliness – taking samples and performing total bacterial counts and total coliform counts – can also be performed on a routine basis. Sample colostrum at the point at which it enters the calf – for example, the oesophageal feeder or nipple feeder – into a sterile milk sample pot and refrigerate between 4°C to 8°C before submitting it to a laboratory (Figure 6). This will allow accurate assessment of how clean colostrum being fed to calves is, and adjustments made to collection, storage or administration can be made as necessary.

Youngstock work is a focus of many vet practices, feed companies, pharmaceutical industries and others associated with farming. While this is certainly good for youngstock on farms in the UK, it can also lead to the farmer receiving mixed messages. Nowhere is this more obvious than colostrum management – especially volumes fed and timings of feeds. The vet is independent, must be objective and be able to offer sound advice.

The answer to what the farmer should do around colostrum management comes from the data the vet can record. If the numbers are good, do not change the system; if the numbers can be improved, make changes and monitor for success.

The feeding of an adequate volume of good quality, clean colostrum as soon as possible after birth is arguably the most significant effect a farmer can have on the life of a cow. The importance of providing the best start for future members of the herd cannot be emphasised enough. It is often difficult to focus on this, however, when other jobs such as milking and feeding adult cows take up a significant proportion of the day.

Providing simple, straightforward colostrum protocols of quality, quantity, quickly and squeaky clean should enable this focus. They are inexpensive, do not take significant amounts of time and are very effective at reducing morbidity and mortality. The ability to develop programmes to routinely monitor colostrum management and measure success becomes hugely rewarding to all involved.