26 Mar 2024

Communicating calf scour messages to farming clients

The authors explore how effetive techniques are key to success in scour prevention.

Image © Monkey Business / Adobe Stock

Scour (Figure 1) is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in pre-weaned calves (Lorenz et al, 2011; Meganck et al, 2014) and is a challenging problem on many farms.

Veterinary surgeons have an important role in advising farmers on strategies to prevent calf scour, as well as assisting farmers to manage outbreaks if they occur.

The recently launched Animal Health and Welfare Pathway (AHWP) aims to enhance veterinary input in the health of the national herd by facilitating annual reviews between farmers and their veterinarians, as well as providing funding to aid in disease eradication and control (Statham and Russell, 2022). While prevention of calf scour is not currently a focus of the AHWP, annual reviews may highlight this, on some farms, as an area for improvement of calf health warranting further discussion. It is known farmer willingness to consider herd health advice is influenced by veterinary communication style (Ritter et al, 2019). Effective communication is, therefore, key to achieving success when advising on calf scour prevention strategies.

This article discusses some approaches to communication with farmers, with a focus on implementation of vaccination programmes and reduction in antimicrobial use.

Communication

Communication is a key part of a veterinary surgeon’s day-to-day role, with many aspects of communication being performed subconsciously.

When attempting to communicate in a way that elicits behaviour change, several core factors need to be considered – namely clients’ perceptions of the situation, their motivations and how they best receive information. These factors are vital for constructing an individual approach to each on-farm situation, tailored to the individual client.

Client perceptions

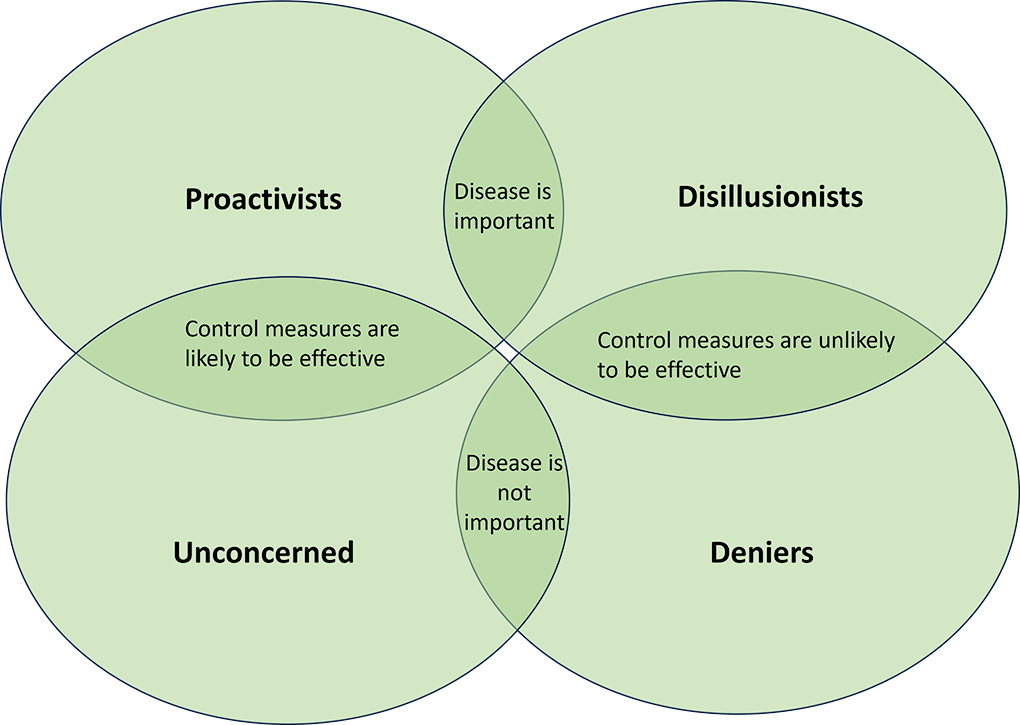

Perceptions relate to an individual’s understanding and interpretation of a situation. Assessing farmer perceptions can be a helpful way to decide where to start with communicating to elicit behavioural change. A Canadian study looking at perceptions of farmers towards control and management of Johne’s disease classified farmers based on their belief in the importance of the disease and then their belief in the proposed control and prevention strategies. This allowed researchers to allocate their farmers to one of four different perception groups: “proactivists, disillusionists, unconcerned and deniers” (Figure 2).

Proactivists were engaged and well informed, and believed in the importance of the disease and the proposed prevention and control strategies. Disillusionists believed in the importance of disease, but were not convinced by the proposed prevention and control strategies. Conversely, unconcerned did not regard Johne’s control and prevention as a priority; they believed in the proposed strategies, but did not believe in their importance. Finally, deniers did not believe in the importance of the disease or the proposed control and prevention strategies.

Based on these categorisations, control and prevention strategies were optimised for each farmer perception quadrant to increase uptake of the recommendations (Ritter et al, 2016). Despite this model being developed for Johne’s disease, it could be easily adapted and applied to other preventive measures as discussed in this article. Ritter et al (2016) concluded that, when perceptions were unfavourable, it was not a lack of knowledge that acted as a barrier to uptake of advice. Therefore, exploring individual farmer perceptions of issues is vital to knowing where to begin with implementing change on farm.

Client motivations

Understanding farmer perception is crucial when considering motivations for change. Motivators can be either intrinsic (for example, job satisfaction, pride in farm or striving for good animal health and welfare) or extrinsic (for example, financial incentives or penalties). Occurrence of a disease process, such as calf scour, is not sufficient to motivate farmers to make change – recognition needs to exist by the farm that the issue requires adjustments to be made, neither can we assume that providing client education will be sufficient to motivate on-farm change. Farmers have many different sources of advice and can be influenced by their own individual situation, but also by their peers, industry and government guidance (Ritter et al, 2017).

It can be easy to fall into the trap of believing money is the primary motivator for on-farm decision-making; however, when considering mastitis management, research has shown internal farm performance factors and individual clients were more motivating than external factors, and that good animal health and welfare were just as motivating as financial and economic performance (Valeeva et al, 2007).

Information delivery

In 2021, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board performed some research aiming to understand how UK producers prefer to access learning that supports a change in behaviour (Williams and Muir, 2021). They used the Honey and Mumford (1982) model of learning styles that categorises learners with one of four preferred styles of learning:

- Activists – characteristics include emersion in new experiences without bias, happy to contribute and enjoy active learning in the moment.

- Reflectors – features include learning through observation and reflection, observe and use other perspectives to draw conclusions.

- Theorists – attributes include learning by collection of data and facts with analysis of these, and the theory behind them; logic is important.

- Pragmatists – traits include requirement for application of theories in the “real world”; suggestions must be functional in practice.

Fifty dairy farmers were interviewed as part of the research (in total, 303 producers from 6 different sectors plus 100 stakeholders categorised into 4 groups, including veterinary surgeons, were recruited). Analysis revealed that dairy farmers had strong preferences for the reflector styles of learning: no dairy respondents identified strongly as activists. Additionally, 82 per cent of dairy respondents had 2 or more dominant learning styles.

By contrast, vets (n = 20) were more likely to identify with activist learning styles; this could either put them at odds with the producers they are working with or fill a gap within on-farm decision-making processes (Williams and Muir, 2021).

Communication tools available

Motivational interviewing

Motivational interviewing was first developed as a conceptual model for eliciting behaviour change in human clients with alcohol addiction and has developed from this starting point (Miller and Baca, 1983). It focuses on adapting communication in response to a client, for instance, using skills such as reflective listening and empathy. Interviews focus on the interviewer encouraging arguments for change by evoking “change talk” and minimising “sustain talk”. Gradually, this technique has filtered through human medicine and is now being used in veterinary medicine.

Evidence for its success in herd health settings have been demonstrated by Bard et al (2022). Conversations around herd health topics were recorded before and after veterinary surgeons were given four to five hours of training on motivational interviewing. Bard et al then analysed farmer and veterinary surgeon verbal behaviour – particularly the influence of veterinarian verbal behaviour on farmer response language.

This research revealed that after motivational interview training, vets used more reflective statements, had a more empathetic and partner-centred consultation style, and used the clients’ own language when discussing positive changes. In turn, farmers responded by engaging better with the conversation and contributing more alternatives for possible changes to herd health on farm. Furthermore, placing emphasis on farmer choice, partnership with the vet and highlighting positive factors from the farmer resulted in more discussion favouring change on farm (Bard et al, 2022).

Application to calf scour

Strategies to prevent calf scour should focus on two fundamental principles: optimisation of neonatal immunity and reduction of pathogen challenge. Colostrum management is key to optimisation of neonatal immunity, but further gains can be achieved by adopting supportive measures such as vaccination. Detailed discussion of approaches to prevention of calf scour is beyond the scope of this article, but is well reviewed elsewhere (Lorenz et al, 2011; Meganck et al, 2014).

Colostrum management

While a paucity of studies investigating the veterinary surgeon’s role in communicating optimisation of on-farm colostrum management exists, principles shown to be effective for communicating other health strategies can be applied.

The framework proposed by Ritter et al (2016; Figure 2) can be modified (for example, by considering failure of transfer of passive immunity [FTPI] as the “disease” and effectiveness of colostrum management as the “control measure”) to facilitate identification of the farmer’s perception of the importance and effectiveness of colostrum management.

Having identified the farmer’s perceptions, the veterinary surgeon can use this information to inform their approach when discussing strategies for improvement.

For example, if a farmer is identified as being disillusionist (that is, they believe FTPI is important, but are not convinced that suggested improvements to colostrum management will be effective), the veterinary surgeon may choose to use testimony from another farmer who has successfully implemented the suggested improvements on their farm to support their suggestions.

Vaccination

Several vaccines targeting calf scour pathogens have been developed (Maier et al, 2022). While vaccines cannot replace good colostrum management, their use can augment calf immunity to specific scour pathogens; accordingly, vaccines can have an important role in prevention of calf scour. Richens et al (2015) found that while farmer perceptions of vaccination varied, general agreement existed about the importance of the veterinary surgeon’s role in the implementation of vaccine programmes.

Furthermore, the veterinary surgeons’ role was considered by most farmers to extend beyond the stage of vaccine supply and into vaccine implementation (Richens et al, 2015), offering opportunities for veterinary surgeons to be involved in the whole process of creating and implementing vaccination strategies. The same research group found that veterinary surgeons typically assign farmers to one of three groups when considering vaccination on farm: proactive farmers who are already engaged with vaccination; receptive farmers who are not yet vaccinating, but are receptive to advice; and uninterested farmers who are disengaged and not receptive to advice (Richens et al, 2016).

Veterinary surgeons reported altering their communication styles depending on which group they perceived their farmers to be in, but the third group of farmers (uninterested) were considered to be a “lost cause” who veterinary surgeons had given up communicating with (Richens et al, 2016). As Richens et al (2015) found that even farmers who took pride in receiving minimal veterinary input recognised the importance of veterinary advice when implementing a vaccination strategy, it is possible that giving up on this group of farmers represents a lost opportunity for veterinary surgeons.

Svensson et al (2020) found clients of dairy veterinary surgeons trained in motivational interviewing techniques were more likely to engage in “change talk” and also reported higher client satisfaction — another factor associated with improved uptake of veterinary advice (Ritter et al, 2019). As such, learning and developing motivational interviewing skills may be a route through which veterinary surgeons can establish effective communication with farmers of this type, possibly leading to improved scour prevention and improved calf health and welfare.

Antibiotic usage

While prophylactic antibiotic treatment has historically been used to reduce enteropathogen challenge as part of a scour prevention strategy, this approach is no longer recommended. Although still allowed in exceptional cases, prophylactic use of antibiotics has been banned in the EU since January 2022 and the UK Government has suggested that similar provisions will be adopted here (Sutherland et al, 2023). The current prevalence of routine prophylactic antibiotic treatment for prevention of calf scour in the UK is unclear, although anecdotally this practice does still occur and it is documented that a high proportion of farmers report using antibiotics to treat calf diarrhoea without confirming a bacterial aetiology (Baxter-Smith and Simpson, 2020; Eibl et al, 2021). Therefore, it is likely that this is an area where further reductions in antimicrobial usage can be achieved.

Additionally, cessation of prophylactic antibiotic treatment to prevent calf scour aligns with one of the long-term aims of the AHWP — a national reduction in antimicrobial use in farmed animals — and information collected as part of annual farm reviews may contribute to government policy in this area (Statham and Russell, 2022). Accordingly, it is likely that veterinary advice on antimicrobial usage will be increasingly sought by farmers in the future.

RESET mindset model

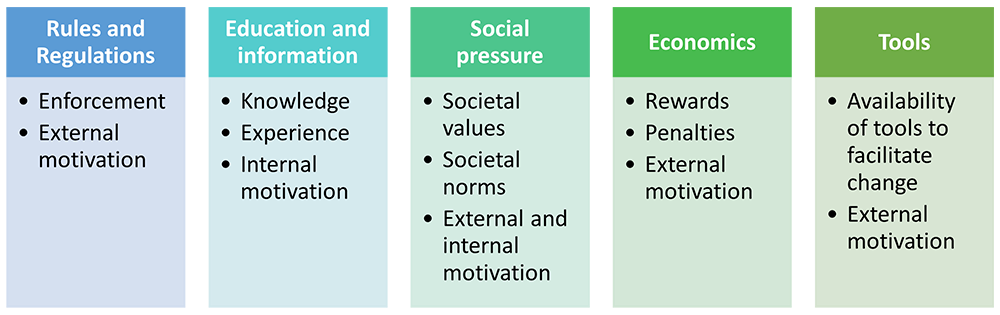

The RESET mindset model (rules and regulations, education and information, social pressure, economics and tools; Figure 3) was designed by a team of researchers in the Netherlands to include essential cues required for human behavioural change.

These cues are not intended to be used individually, but collaboratively to effect change within a large group of people – the concept being that different cues will motivate different individuals and that overlap exists between the cues. This model has been used successfully to achieve a decrease in antimicrobial usage within the Dutch dairy industry (Lam et al, 2017) and has potential for use here.

Proposed legislation to ban prophylactic use of antibiotics fulfils the first step of the RESET mindset model (“rules and regulations”; Figure 3). Nevertheless, it needs to be considered that while individual farmers have responsibility for reducing antimicrobial usage on their farms, and the veterinarian has a role in supporting this aim, large-scale reductions at industry level require input and cooperation of all stakeholders in the dairy industry, not just individual farmers (Lam et al, 2017).

Conclusion

Scour is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity in calves, and can be challenging to manage. Prevention strategies should aim to combine optimisation of calf immunity with reducing pathogen challenge.

Veterinary surgeons have an important role in advising on measures that can realise these aims and effective communication is key to achieving successful implementation.

Vet Times Livestock (2024), Volume 10, Issue 1, Pages 12-17

References

- Bard AM, Main DCJ, Haase AM, Whay HR and Reyher KK (2022). Veterinary communication can influence farmer change talk and can be modified following brief motivational Interviewing training, PLOS One 17(9): e0265586.

- Baxter-Smith K and Simpson R (2020). Insights into UK farmers’ attitudes towards cattle youngstock rearing and disease, Livestock 25(6): 274-281.

- Eibl C, Bexiga R, Viora L, Guyot H, Félix J, Wilms J, Tichy A and Hund A (2021). The antibiotic treatment of calf diarrhea in four European countries: a survey, Antibiotics 10(8): 910.

- Lam TJGM, Jansen J and Wessels RJ (2017). The RESET Mindset Model applied on decreasing antibiotic usage in dairy cattle in the Netherlands, Irish Veterinary Journal 70(1): 5.

- Lorenz I, Fagan J and More SJ (2011). Calf health from birth to weaning. II. Management of diarrhoea in pre-weaned calves, Irish Veterinary Journal 64(9): 9.

- Maier GU, Breitenbuecher J, Gomez JP, Samah F, Fausak E and Van Noord M (2022). Vaccination for the prevention of neonatal calf diarrhea in cow-calf operations: a scoping review, Veterinary and Animal Science 15(8): 100238.

- Meganck V, Hoflack G and Opsomer G (2014). Advances in prevention and therapy of neonatal dairy calf diarrhoea: a systematical review with emphasis on colostrum management and fluid therapy, Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 56(1): 75.

- Miller WR and Baca LM (1983). Two-year follow-up of bibliotherapy and therapist-directed controlled drinking training for problem drinkers, Behavior Therapy 14(3): 441-448.

- Richens IF, Hobson-West P, Brennan ML, Lowton R, Kaler J and Wapenaar W (2015). Farmers’ perception of the role of veterinary surgeons in vaccination strategies on British dairy farms, Veterinary Record 177(18): 465.

- Richens IF, Hobson-West P, Brennan ML, Hood Z, Kaler J, Green M, Wright N and Wapenaar W (2016). Factors influencing veterinary surgeons’ decision-making about dairy cattle vaccination, Veterinary Record 179(16): 410.

- Ritter C, Jansen J, Roth K, Kastelic JP, Adams CL and Barkema HW (2016). Dairy farmers’ perceptions toward the implementation of on-farm Johne’s disease prevention and control strategies, Journal of Dairy Science 99(11): 9,114-9,125.

- Ritter C, Jansen J, Roche S, Kelton DF, Adams CL, Orsel K, Erskine RJ, Benedictus G, Lam TJGM and Barkema HW (2017). Invited review: determinants of farmers’ adoption of management-based strategies for infectious disease prevention and control, Journal of Dairy Science 100(5): 3,329-3,347.

- Ritter C, Adams CL, Kelton DF and Barkema HW (2019). Factors associated with dairy farmers’ satisfaction and preparedness to adopt recommendations after veterinary herd health visits, Journal of Dairy Science 102(5): 4,280-4,293.

- Statham J and Russell J (2022). Introducing the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway: role of the farm vet, In Practice 44(10): 596-602.

- Sutherland N, Coe S and Balogun B (2023). The use of antibiotics on healthy farm animals and antimicrobial resistance, House of Commons Library, bit.ly/3wNZePB (accessed 25 January 2024).

- Svensson C, Forsberg L, Emanuelson U, Reyher KK, Bard AM, Betnér S, von Brömssen C and Wickström H (2020). Dairy veterinarians’ skills in motivational interviewing are linked to client verbal behavior, Animal 14(10): 2,167-2,177.

- Valeeva NI, Lam TJGM and Hogeveen H (2007). Motivation of dairy farmers to improve mastitis management, Journal of Dairy Science 90(9): 4,466-4,477.

- Williams B and Muir K (2021). An analysis of the learning styles preferences of UK farmers, growers and industry stakeholders, bit.ly/3wO427B