12 Oct 2021

Dealing with owners’ perception of obesity

Tamzin Furtado uses insights from human health behaviour change to explain how veterinary professionals can facilitate communication around complex equine welfare topics such as obesity.

Image: chelle129 / Adobe Stock

Human behaviour is at the core of veterinary practice, and a lack of effective communication between veterinary staff and clients can result in poor outcomes – ranging from poor compliance with treatment, to the owners’ lack of trust in the practice or even veterinarians as a community.

As clients increasingly inform their opinions from information online, vet‑client relationships have never been more important, or perhaps more strained. The veterinarian’s ability to build relationships, and communicate clearly and empathetically are particularly key in sensitive topics such as obesity management, during which veterinarians may feel particular frustration with clients1.

This review will consider insights from research in human health behaviour change, and whether such approaches may facilitate the communication of complex conversations in veterinary medicine.

Paternalistic communication

Veterinary communications are most often paternalistic, with the veterinarian in the role of educator and the client in the role of passive learner2.

While in straightforward cases this approach may work well, in many common veterinary issues – such as equine obesity, equine asthma and management of equine ageing – prolonged client behaviour change may be necessary.

A paternalistic approach aims to increase the client’s knowledge of the issue and motivation to change, but does not take into account the important internal and external factors that are relevant in shaping the client’s behaviour and animal’s condition, and therefore may be unsuccessful in bringing about change3.

Secondly, this approach can come across as negative or even confrontational, which can make the client defensive and resistant to change4.

Partnership-based communication styles are recognised as the “gold standard” in veterinary communication, but can be difficult to achieve in practice5, particularly given the culture of paternalistic communication across medicine.

Unfortunately, teaching communication skills is not necessarily the answer to the problem. Two meta‑analyses of communication skills training interventions – in medical students and nurses, respectively – found only limited effectiveness of training interventions6.

It is likely that communication styles and relationship-building skills are deeply embedded in our personalities and identities, and may be difficult to change based on education alone. Indeed, a study of veterinary communication found the skills acquired to navigate client relationships and consultations were built partly through indirect and subconscious processes, such as watching other vets, and not necessarily through educational workshops7.

As used successfully in modern nursing education, the solution relies less on learning formulaic skills of communication, and more on building the relationship between client and practitioner6.

Self-determination theory

Studies from psychology and behaviour change provide useful foundations on which to build consults when change is required, rather than relying on formulaic communications skills.

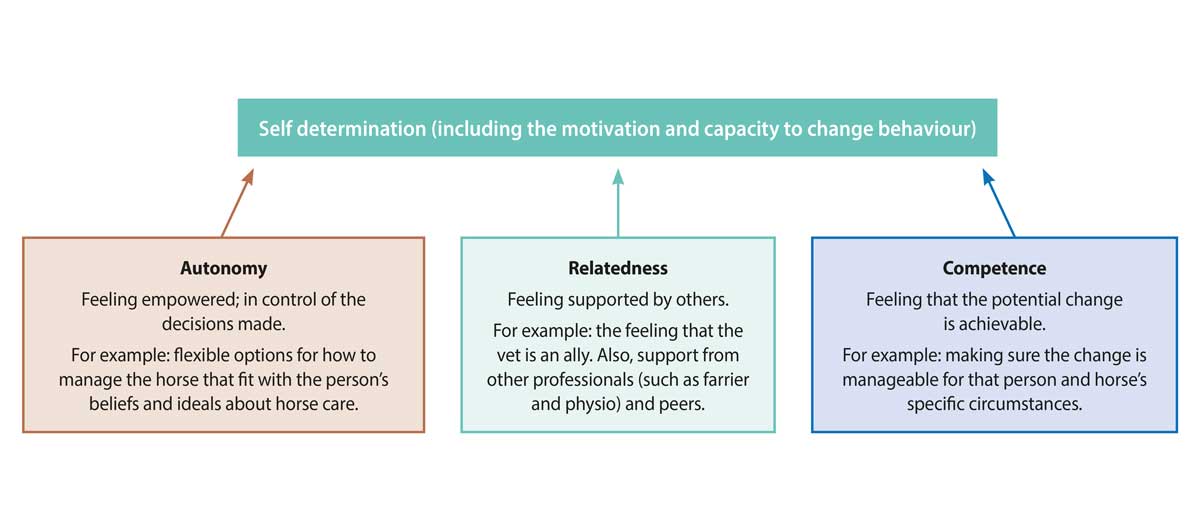

One particularly useful and well-evidenced theory, self-determination theory (SDT), suggests people are most likely to change when three basic psychological needs are met:

- autonomy in decision-making (it is that person’s choice to make the change and to choose how to go about it)

- a sense of competence in making the change (a sense that the change and each step towards that change is achievable)

- a sense of support (for example, from peers and professionals)8,9

SDT therefore suggests that clients need to be in a positive frame of mind to be able to effect change; they need to believe in the change, in their own ability to make the change, and to believe they have the social support to help them.

The idea of the positive mindset as a prerequisite for ongoing change is supported by numerous other behaviour change scientists10-12. Indeed, when an alternative approach is taken and the person is challenged or made to feel negative about his or her choices (for example, when presenting scientific evidence to those who choose not to vaccinate), research has shown that people believe in their choices even more strongly than they did before the conversation – they become even more resistant to change13.

SDT’s principles of encouraging a positive mindset and belief in self-efficacy could be easily translatable to consults in the veterinary field when change is required. However, the nature of how such approaches can be applied will differ depending on the nature of the consult – for example, whether the change is short-term or long-term, difficult or easy for the client and horse, and the personality and identity of both veterinarian and client.

Short-term change

Short-term changes – such as the need to give a medication for two weeks, or the treating of a wound – should be more straightforward for veterinarians to encourage because the change is short-term and, therefore, does not require prolonged client motivation.

Also, with such changes it is likely the client’s desire for effectiveness, and reward of seeing that effectiveness in practice over the relatively short time span, will be enough to ensure the client is able to carry out the change.

However, a recent report suggested that even apparently simple changes – such as giving medication – are more difficult for the client than might be expected5, and hence ensuring client compliance with short-term medical advice may still require veterinarian attention.

Here, the principles of SDT can be usefully applied. For example, one common reason for failure to give medication might be the animal refusing the medication; a negative experience for both horse and owner, which will threaten the owner’s sense of competence. Similarly, wound treatment may be difficult if the horse becomes anxious, or owners may be concerned about the ongoing cost of supplies.

Therefore, conversations that ensure the client’s sense of competence, but also ensure he or she feels he or she has ongoing support if problems occur, may help to ensure maintained change in the short term.

Chronic issues/lifestyle change

For issues that will require a longer-term lifestyle change – such as the management of obesity, pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction, equine asthma or gastric ulceration – it is even more important that the aspects of self‑determination theory are adhered to, so that the client believes he or she has the ability and support to make the change.

Moreover, behaviour change theorists argue we are more likely to be able to sustain change when that change is congruent with our belief systems10. For example, if an owner believes strongly that horses should never have limited access to forage, that owner will unsurprisingly be less motivated or able to put a horse on a forage‑restricted diet, as is often recommended for initial obesity management14. Furthermore, telling this owner to do so is likely to be incongruent with his or her sense of autonomy (because the owner will feel he or she is being asked to do something he or she does not like) – and as a result may seek support from others who share his or her own views, so as to retain a sense of support as required by our basic psychological processes.

When sustained change is necessary, it is also important to consider the social and environmental factors that may either support or hinder the change. Both factors are powerful influencers of change15, but can be overlooked in veterinary communication.

For example, many horse keepers stable their horse at a livery yard, where their options for change may be limited either by the livery yard manager or by peer pressure16.

Similarly, those people can be supportive of change if the change fits with their belief systems and management.

Discussing with owners how they may be influenced by external factors can pay dividends in ensuring they can maintain change over time.

The horse aspect

Given that behaviour change theories are created for human health, they do not account for another important contributor to change – the horse.

Horses are adept at communicating their likes and dislikes for management changes, and an unhappy horse that is showing its displeasure through being grumpy (for example, when dieting) or by making it difficult for the owner to carry out the new management regime (for example, jumping out of its paddock) will significantly contribute to the owner’s sense of competence in making the change.

Furthermore, given that owners are deeply invested in their relationship with the horse, they may find it difficult to make changes that appear to have negative welfare impacts or well-being on the horse, even if they are short-term. Therefore, management that uses positive well-being components are more likely to be manageable in the long term. This can include using alternative grazing management systems that alter the environment, but still allow horses to be turned out alongside conspecifics; and by using extensive enrichment, which creates a positive experience for both the horse and owner17.

Therefore, for chronic or ongoing issues, it is important to work with the client to form an individualised plan that will fit with the owner’s abilities and belief systems, the horse’s likes/dislikes, and the environment within which that person keeps the horse.

While this may seem a tall order for a consult, it is possible to use insight from behaviour change counselling to manage this process in a time-efficient manner, by encouraging the owner to take the lead in suggesting the types of changes he or she thinks will suit him or her best. This has the added benefit of furthering his or her sense of autonomy about making the change.

The owner’s ideas can then be adapted with the help of the veterinarian to ensure congruence with the horse’s condition.

Insights from behaviour change counselling

Behaviour change counselling is specific to situations where human change is necessary, and the most well-known approach is “motivational interviewing” (MI).

This approach derives from addiction counselling, and is now well-used and evidenced in human medicine across situations where change is necessary – for example, in health (addiction, heart disease, smoking, dieting) and psychology (for example, parenting interventions)18.

While most communicative and counselling approaches advocate active listening skills, reflections (reflecting the participants’ views back at them) and open questions, behaviour change counselling takes this approach further by employing the use of affirmations, and specific types of reflections that empower clients by encouraging them to describe their own reasons for wanting to change and their own ways of going about making those changes18.

This approach has had increased interest in its usefulness in the veterinary arena in recent years19-21.

MI approaches offer particular opportunities in veterinary medicine, given that it is designed to be a “brief” therapy that could therefore be employed in busy settings, and that it is particularly useful for empowering clients to make changes congruent with their belief systems around the issue at hand.

An MI approach to an obesity consult, for example, may encourage the owner to describe the reasons he or she thinks it is important to reduce his or her horse’s weight, to consider what initial steps he or she might like to make, what success would look like, what issues he or she may face along the way, and the ways he or she will overcome those steps.

In this approach, the client is in the role of being the expert in his or her own life and his or her own ability to change, while the professional is a facilitator or enabler of change and may provide expert advice – for example, on the technical aspects of the change (answering the client’s questions about technical aspects of the change to the horse’s care, in this instance).

Conclusion

Veterinarian communication around horse owner behaviour change can be supported through insights from the behavioural sciences.

The application of theories such as SDT highlights common pitfalls in communication, which may be particularly applicable in situations where prolonged lifestyle changes are necessary.

Behaviour change science suggests that using principles of positive communication, and conveying a sense of autonomy and empowerment of the client are most likely to result in prolonged change.