26 Feb 2025

Exotic notifiable diseases of cattle of current importance

Phil Elkins BVM&S, CertAVP(Cattle), MRCVS discusses some of the notifiable pathogens potentially impacting ruminant species this year.

Image: Chris Brignell / Adobe Stock

A number of cattle diseases exist that have been designated by the relevant authorities as notifiable – that is to say, any suspicion of disease must be reported by the vet to either the APHA in England, Wales and Scotland, or to the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) in Northern Ireland.

These diseases have been designated as such either because they are of global animal health importance, as recognised by the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), or of national animal health importance, as recognised by the APHA/DAERA.

Notifiable diseases may be endemic to the UK, such as bovine tuberculosis, or exotic, such as contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, which was last seen in the UK in 1898. For those exotic diseases, veterinary surgeons acting on behalf of private practices, at abattoirs, collection centres such as markets, or at border posts act as an important part of the surveillance network, as was demonstrated by the 2001 foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak.

As such, it is especially important for vets working in these areas to be aware of the disease presentations for those diseases more likely to be seen in the UK due to their current spread. The APHA offers a subscription service with notifications when an exotic notifiable disease is identified in Great Britain (tinyurl.com/5xda9v9p). Equally useful is the WOAH World Animal Health Information System subscription, which notifies of any disease outbreaks of WOAH designated listed diseases (tinyurl.com/ykh7r6sc). It is worth noting that the two lists of notifiable/listed diseases are not identical; for example, bovine viral diarrhoea is WOAH listed, but is considered endemic in the UK and, therefore, not notifiable at an individual animal/holding level.

A list of all notifiable diseases is available on the Defra website (tinyurl.com/4nm798e4).

This article will focus on the main diseases of cattle of likely significance to veterinary surgeons at the moment. As with all epidemiological reports, the picture is ever-changing and will be reported here correct at the time of writing.

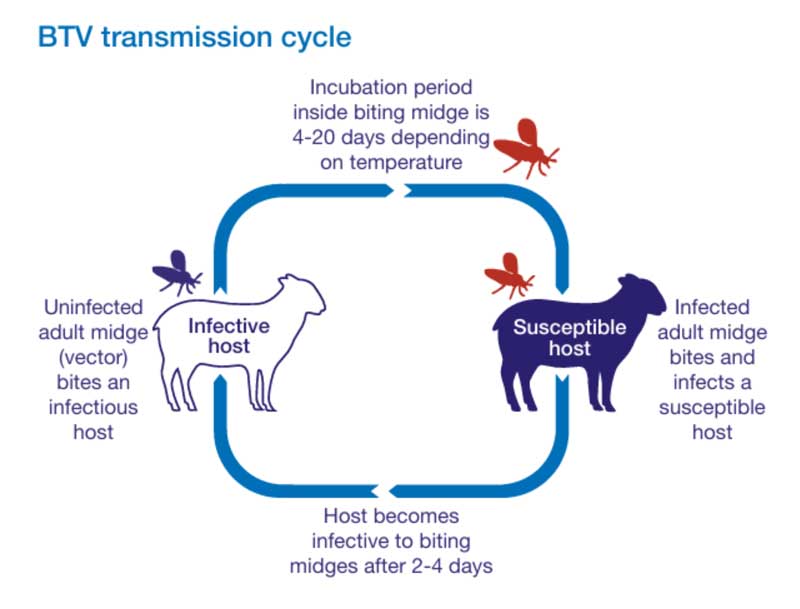

Bluetongue

Bluetongue is a non-contagious, vector-borne viral disease caused by an Orbivirus. Culicoides midges can become infected via feeding behaviour on an infected host. Following a replication period of six to eight days in the midge salivary gland, the midge becomes infective and will be for life (usually a few weeks). The newly infected host then becomes infective after two to four days, and remains so for up to 60 days.

Bluetongue can also be spread vertically or through germinal products (sperm or ova). Bluetongue can affect all ruminants and pseudo-ruminants (such as alpacas and llamas).

Bluetongue first entered the UK in 2007, and following an extensive surveillance campaign and vaccination, the UK was declared bluetongue free in 2011. The causal serotype was BTV-8, and despite a widespread outbreak in France in 2016, the UK maintained that status until late 2023.

As described previously, bluetongue spread is dependent on midge vectors, and as such an expected seasonal pattern to detection exists.

Following an initial case of BTV-3 in November 2023, a further 125 cases were identified through until March 2024, with all cases believed to have been infected in the autumn.

The absence of further disease in the spring led to the assumption that the UK was free from overwintered BTV-3 in early 2024. On 26 August 2024, BTV-3 was identified on a farm in Norfolk, with presumptive spread from continental Europe.

This incursion was not unexpected, and the APHA provided information via a webinar to vets in April 2024 highlighting the risks and the need for vigilance. Serotypes 4, 8 and 12 have also been reported in the continent.

Current situation

The total number of cases in the 2024-2025 outbreak of bluetongue in the UK is 200 (at time of print), as reported by the APHA. This includes cases throughout England and Wales, with cases still being identified in January.

The most common region for bluetongue cases has been coastal eastern England, fitting with a likely spread to the country via infected midges across the sea from the continent. One case was identified in Devon as a result of post-movement testing in an imported animal and was promptly culled. The rest of the consignment tested negative, with no indications of onward spread.

The increasing number of cases in the UK prompted the designation of a restricted zone and infected area. This now includes a large proportion of England.

The aim of the restricted zone is to limit the spread of bluetongue to the unrestricted areas through transportation of infected stock, while not preventing trade and movement either within the restricted zone or from units in the unrestricted zone.

Animals may not move from within the restricted zone to outside the restricted zone without the prior provision of a licence by a veterinary inspector.

Given the risk of spread via germinal products, no sperm or ova can be frozen within the restricted zone unless frozen on premises licensed specifically for this.

A map of the current restricted zone can be found on the Defra website.

Clinical signs

Sheep are more likely to show clinical signs than cattle. Clinical signs are caused by damage to the vascular epithelium and, in sheep, include:

- Fever.

- Ulceration and/or swelling of the mouth and nose.

- Ocular or nasal discharge, drooling from the mouth.

- Swelling of the lips, tongue, neck and head.

- Heat and tenderness of the coronary band, causing lameness.

- Inappetence and weight loss.

- Abortion, fetal deformities and stillbirths.

- The clinical signs in cattle are far more mild, with many animals being asymptomatic:

- Lethargy, fever and milk drop.

- Crusting and erosions of the muzzle and nostrils.

- Conjunctivitis and tear staining.

- Redness of the mouth, eyes

and nose, with discharge sometimes present. - Reddening of the teats, hooves and interdigital space.

- Abortion, fetal deformities and stillbirths.

Infected fetuses may be born weak, deformed or blind, and may die within a few days.

If presented with an animal with these clinical signs, it should be reported immediately to the APHA or DAERA. Limited measures are available to individual farmers to reduce their risk of contracting bluetongue on their farm. While, theoretically, reducing the presence of midges through insecticide use may seem logical, the midges need to bite first before the insecticides kill them, allowing spread to have already occurred. Farmers could consider housing at dusk and dawn during the midge season to reduce the exposure for biting, and should consider responsible sourcing of stock.

The two main control measures available are vigilance for disease intrusion, with reporting if suspected to prevent further spread, and vaccination of stock. Four different vaccines are available for BTV-3: these are to be used under VMD authorisation, although not licensed.

All four claim to reduce viraemia rather than prevent it, and as such will reduce spread within a flock/herd rather than prevent it entering.

The modelling suggests that as vector activity is lower at this time of year, further outbreaks in the next couple of months are unlikely.

However, we must remain vigilant to spot cases early in the next vector season to reduce the risk that bluetongue becomes established throughout the vector season in 2025-2026.

FMD

At the time of writing, Germany has just declared an outbreak of FMD. Many practising vets will be able to remember the 2001 outbreak in the UK, but an increasing proportion will not.

The devastation caused led to many farm businesses closing having seen their stock all slaughtered, with consequences that spread far and wide. For example, the rate of bTB increased dramatically following the outbreak due to delayed testing during that period, and movements of cattle across the country to restock in the absence of pre-movement testing.

Current situation

It is plain to see that an outbreak of FMD in the UK that establishes and spreads prior to detection could wreak similar havoc. As a result, the UK Government has acted quickly to reduce the risk further of import from Germany:

- The commercial import of susceptible stock or their products from Germany is prohibited.

- No further GB health certificates will be issued for animals, fresh or processed meat from susceptible species.

- Travellers are not allowed to bring unpackaged meat, meat products, milk or dairy products from the EU, European Free Trade Association states, Greenland or the Faroe Islands.

Appropriate biosecurity within the UK becomes increasingly important with the proximity of the disease. FMD may be infective prior to significant clinical signs, and so the disease may spread quickly.

Private vets should not only be ensuring their own biosecurity using a disinfectant with a Defra-approved FMD order at the appropriate dilution, but also encouraging enhanced biosecurity from clients.

Clinical signs

The primary role for vets is vigilance. Spotting suspect cases early will reduce the spread of disease.

FMD is a highly contagious, viral disease of ruminants, pigs and other cloven-hoofed animals such as camelids and deer.

Cattle typically develop vesicles, which may present as sores or blisters, as they are often burst before presentation.

This leads to the following clinical signs:

- Lesions on the feet where the hoof meets the skin, or between the claws.

- Lesions in the mouth or on the tongue.

- Pyrexia, inappetence, shivering, lameness or drooling.

Sheep rarely develop mouth lesions, with lameness being the predominant sign. This is usually severe and rapidly spreads through the flock, with an unwillingness to move and fertility losses. Blisters may be small and hard to spot.

Pigs similarly rarely develop blisters, with the primary sign severe lameness, in some cases causing the pig to squeal loudly. Affected pigs are usually unwilling to move and reluctant to feed.

For further information on notifiable diseases of cattle or other species, visit the Defra website.

It is worth reviewing regularly, as the situation can change rapidly. For example, at the time of writing, peste des petites ruminants is present and spreading through eastern Europe.

- Vet Times (2025), Volume 55, Issue 7, Pages 6-8

- Phil Elkins qualified in 2005 from The University of Edinburgh and, following stints in Cheshire and New Zealand, spent the majority of his career in clinical practice in Cornwall, during which time he gained a certificate in advanced veterinary practice in cattle. Following 15 years in clinical practice and a stint working for an agri-tech company, Phil now works as an independent consultant to both farms and industry bodies. He is a former council member of the BVA.