20 Sept 2022

Finding eggs in bovine faeces – is it a fluke?

At BCVA Congress, Claire Reigate presented results on fluke egg recovery from bovine faeces, using both spiked and naturally infected samples. In this article, Claire and colleagues – Hefin Williams, Russ Morphew and Peter Brophy – consider faecal egg counts and how they are integral to on-farm parasite control strategies, introduce a new fluke faecal egg counting method, and discuss how fluke faecal egg counts can be used in detecting ruminant fasciolosis…

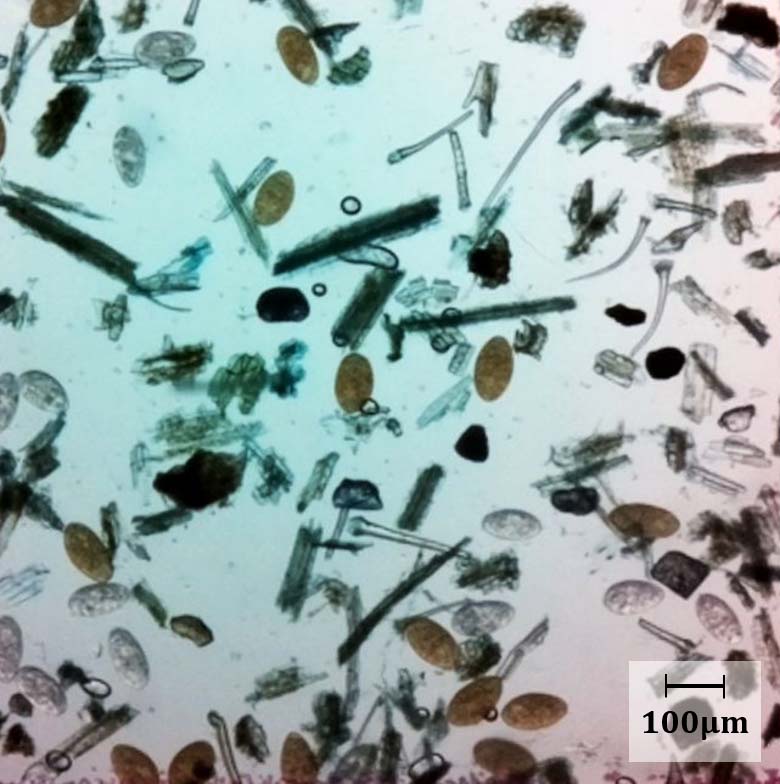

Figure 1. Eggs of Fasciola hepatica (golden) and Calicophoron daubneyi (colourless), imaged using the Micro-I 100.

Faecal egg counts (FECs) are the cornerstone diagnostic technique used by parasitology researchers, clinical practitioners and by livestock farmers, principally to diagnose gastrointestinal nematode (GIN) infections in grazing animals.

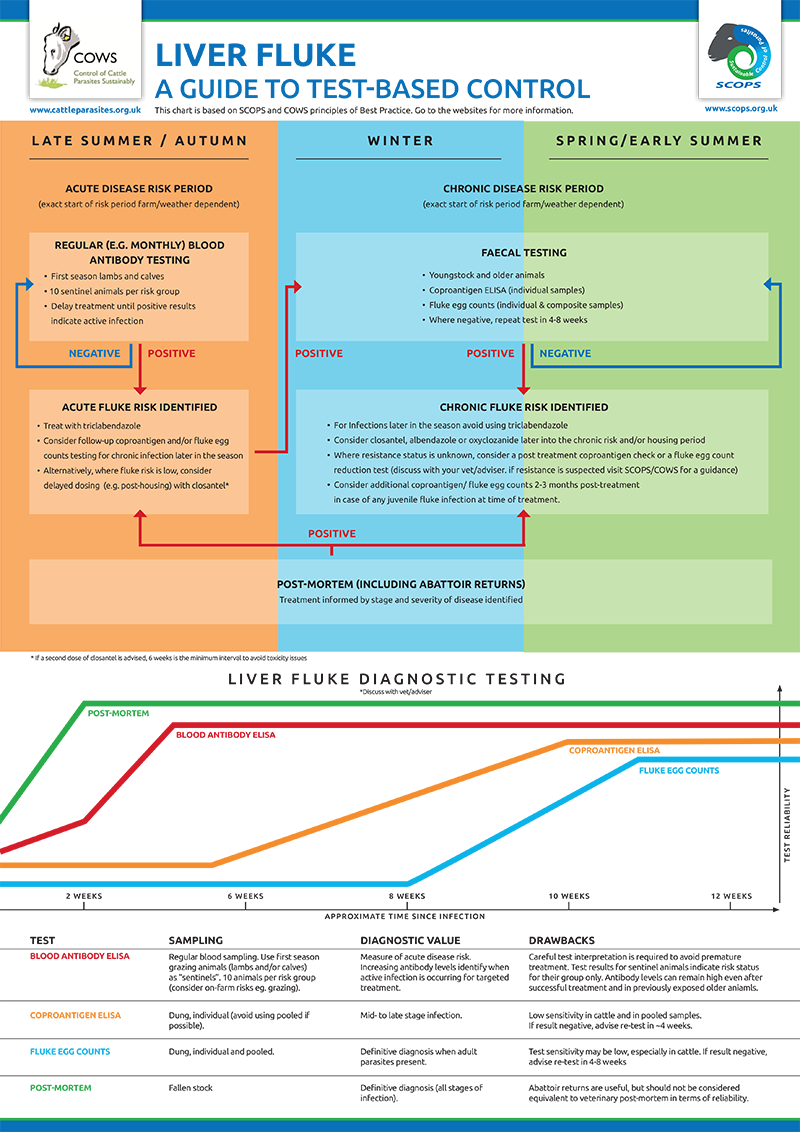

FECs are a familiar practice among most British livestock farmers, as farm advisory services and industry-led initiatives – Sustainable Control of Parasites in Sheep (SCOPS) and Control of Worms Sustainably (COWS) – have strongly advocated for years that pasture‑based livestock farmers use regular FECs to monitor GIN infections in their grazing animals, inform treatment and grazing management decisions, and evaluate parasite control plans.

FECs for GINs are relatively inexpensive and require simple laboratory equipment to perform, making them an accessible pen‑side diagnostic; however, the current methods are not suitable for detecting liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) eggs.

GIN FEC protocols commonly employ saturated saline as a flotation solution to concentrate the GIN eggs to the surface of a slide or chamber, to then be quantified using a microscope or imaging device.

Liver fluke eggs are dense, oval and operculate, and they instantly distort or rupture when exposed to salt-based solutions – making flotation FEC techniques inappropriate for liver fluke egg detection.

As such, most laboratories employ a sedimentation-based method to recover the liver (and rumen) fluke eggs from faeces, then stain the sample using methylene blue.

Fresh F hepatica eggs are a deep, golden colour from bile and stand out among the blue‑stained faecal debris. Colourless paramphistome (rumen fluke) eggs, however, are a little less obvious, but, nevertheless, relatively easy to see in a faecal sample (Figure 1).

FECPAKG2 is a field‑based, high‑resolution image‑based FEC system used by farmers, veterinary practices and retailers in the UK to detect GIN infections. The standard FECPAKG2 protocol uses saturated saline to float the nematode eggs and was found to be unsuitable for detecting fluke eggs, so a new fluke FEC protocol – using an amalgamation of the Flukefinder-FECPAKG2 system – was developed (FF-FECPAK).

The precision, fluke egg detection threshold, and fluke egg recovery rate were determined using artificially spiked sheep and cattle faeces (Reigate et al, 2021), and the FF-FECPAK method was evaluated using naturally infected cattle faeces and compared to other fluke FEC methods. The latter results are being presented at BCVA Congress.

The method of egg recovery from faeces is not the foremost difference between GIN and flukes; many notable differences exist in fluke biology, life cycle, epidemiology, and seasonal and environmental drivers. They have important consequences for the use and interpretation of fluke FECs.

The implications for fluke control strategies are outlined below.

Conclusion

Fluke FECs are a simple, attractive fluke diagnostic with high specificity that can be performed on-farm, in most veterinary practices or agri-merchants, and thereby giving farmers relatively instant results on which to base treatment and grazing decisions.

Regular fluke FECs should certainly be encouraged, but as most farmers are well acquainted with the interpretation of FECs for GIN infections, the authors warn that as the biology and epidemiology of fluke is very different to GINs, this influences how fluke FECs are used and interpreted.