24 Nov 2016

Getting to grips with youngstock

Kathryn Hart and Oliver Tilling discuss how vets can get more involved with youngstock, both proactively and regularly.

Image © RyanMcGuire / Pixabay

Numbers of youngstock can equal numbers in the adult herd on many UK dairy farms, yet veterinary involvement is often very limited. In fact, Atkinson (2015) found only 40% of farms had frequent vet involvement with their youngstock.

An involvement in calf rearing is the first chance to have an effect on the future herd. If done well, this can have impressive and quick results, leading to the strengthening of vet and farmer relationships.

Getting a foot in the door

If 40% of farms have regular input from their vet into their youngstock, 60% do not – so how do you engage with these?

It is about identifying opportunities where this can happen – and they present themselves in different ways. For example, the new graduate might spend a lot of time TB testing.

While this is a mundane job, it offers the chance to see the whole herd in one go and can help start conversations about youngstock management.

For example, when running bulling heifers through, questions such as “how old are they?” or “what weight do you think they are?” are a way in.

When catching weaned calves, questions such as “do you often see a dip in growth after weaning?” or “do your calves suffer from pneumonia around weaning?” can help, too.

Young vets, meanwhile, are more likely to see an individual sick calf.

It is easy to inject and leave, but, if handled well, the interaction can lead to a useful conversation about general calf health or treatment protocols.

Trying to get a revisit to see the calf and assess others in the age group is a first step.

A difficult calving is part of cattle practice, but once the calf is delivered, asking about follow-up management and discussing ideas around, for example, colostrum management, navel dipping, disease risks, and how soon to separate cow and calf, demonstrate an interest, allowing the farmer to recognise a level of expertise in the vet.

Obviously, scour or pneumonia outbreaks offer more significant opportunities as the farmer is acutely aware of the heavy losses they are being subjected to.

Again, it’s not about solving the outbreak; it’s more about offering long-term management changes in forms such as colostrum, feeding, housing and vaccination.

Buying in to a practice or individual’s youngstock expertise requires enthusiasm and initiative, and is only achieved if the farmer asks you for further input.

Where do you start?

If you can get your foot in the door, you’ve got to know where to start to make positive changes and get some early wins.

Firstly, attend the authors’ workshop at congress – this will provide the knowledge and confidence to succeed.

Once on the farm, you first have to deal with the farmer’s initial concerns – and the first place to look for answers is, almost certainly, always going to be colostrum management.

The five Qs of effective colostrum management are (Tilling, 2014):

- quality

- quantity

- quickly

- squeaky clean

- quantify

Sound knowledge and advice around numbers one to four are essential.

However, we must be able to monitor progress to demonstrate success – and quantifying focuses on measuring passive transfer, through the blood sampling calves, can do this.

Several laboratory tests exist, but serum total protein by refractometer is the most reliable for herd screening (Weaver et al, 2000) as it’s simple, rapid and inexpensive.

All farm veterinary practices should have the necessary equipment.

A serum total protein concentration of 5.2g/decilitre is equivalent to an immunoglobulin G concentration of 1,000mg/decilitre. Therefore, on a healthy, adequately hydrated calf a serum total protein of 5.2g/decilitre or greater is associated with adequate passive transfer.

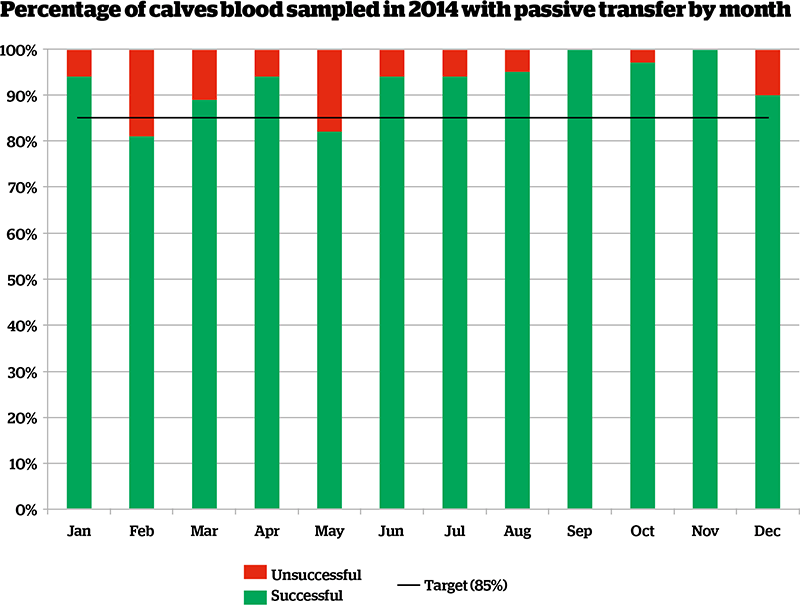

Regular monitoring of colostrum management by blood sampling calves enables long-term patterns to be built up (Figure 1).

A target of greater than, or equal to, 85% of all calves sampled having greater than, or equal to, 5.2g/decilitre is readily achievable.

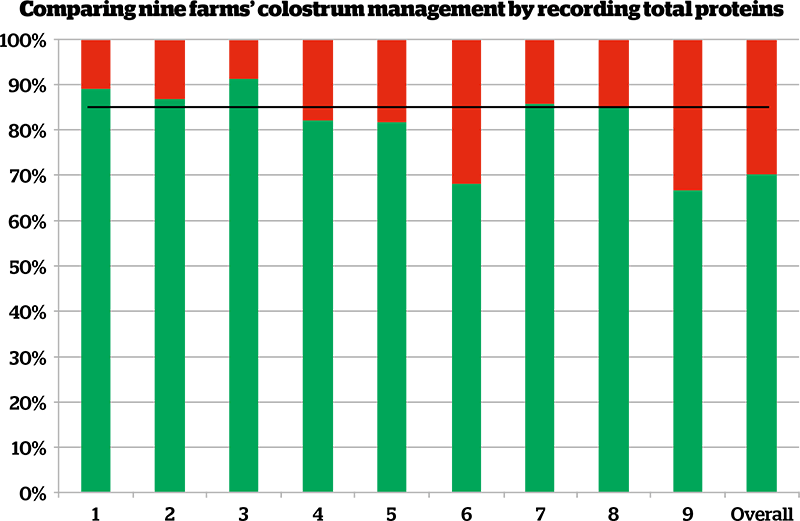

Monitoring also allows benchmarking between farms (Figure 2) as well as comparing disease levels with total protein levels.

A strong association between failure of passive transfer (FPT) and the routine measurement of serum total protein in heifer calves has been observed.

The odds of FPT are nearly 14 times higher on farms not routinely monitoring total proteins to assess passive transfer compared to those that do (Beam et al, 2009). Improving colostrum management, and ultimately reducing FPT, is, logically, a focus of farms that routinely evaluate the passive transfer status of their calves.

Colostrum cleanliness, as in taking samples and performing total bacterial counts (TBC) and total coliform counts (TCC), can also be routinely performed.

Sample colostrum at the point it enters the calf – such as the oesophageal feeder or nipple feeder – into a sterile milk sample pot and refrigerate at 4°C to 8°C before submitting to a laboratory.

Targets are a TBC count of lower than 100,000 colony-forming units per millilitre (CFU/ml) and a TCC count of lower than 10,000 CFU/ml. This will allow accurate assessment of how clean the colostrum being fed to calves is and adjustments to collection, storage or administration as necessary.

Of course, several other avenues must be considered, including calving management, feeding, housing and disease, but colostrum offers an excellent starting place to make early gains, and offer vet and farmer confidence.

What data is needed?

Lack of data must not be used as an excuse for not getting involved in calf health reviews.

Much can be pulled from the way the calves look at the time of the visit:

- rumen fill

- body condition score

- Wisconsin score (Figure 3)

- availability of water

- feed and forage

- incidence of scour and pneumonia

Most farms will have some records of treatments and mortality – while these are rarely perfect, they are a good starting point.

Information from the veterinary practice management system about numbers of pneumonia antibiotic or rehydration sachets bought offer a rough idea of disease incidence.

Be aware treatment rates will appear to increase after you start focusing on calf care.

However, this is often due to an increase in recording and/or more accurate identification of disease, rather than treatment rates alone.

Birth and weaning weights are ideal to give an overall assessment of calf health (Figure 4). These are still rarely available, but can become part of a regular monitoring service. Collecting total protein data, weights, disease incidence and others over time will build a clear – and hopefully improving – situation.

Creating a service

So how do you get from the sick calf or late-night calving to a so-called “youngstock routine”?

It clearly doesn’t happen overnight and, like fertility routines, is likely to become bespoke to each client.

It is often best to focus on one particular area rather than trying to encompass every aspect from birth through to when the calf enters the adult herd.

Presenting the farmer this all-encompassing package of measures is likely to be initially rejected as “too much to do”; start small and then build the service out.

At Shepton Veterinary Group, using funding from MSD Animal Health, the Keeping Britain’s Youngstock Healthy scheme was used for a calf data-mining exercise on 10 farms with historical youngstock involvement with the practice.

This data, plus total proteins and weights of all calves up to 100 days (all recorded on one day), were then analysed. A unique report was provided to each client, with a benchmarking meeting held.

Following this, a new service was launched.

In this service, veterinary technicians performed most of the data collection, which was reviewed by the vet.

Reports were then provided and follow-up advice or visits by the vet taken as needed.

This service has since been rolled out to other clients in the practice.

At the George Veterinary Group, an initial visit was heavily subsidised by pharmaceutical companies using supported testing – such as calf side scour tests, species-identified coccidiosis sampling and blood testing – to show exposure to common pneumonia viruses.

This got the vet on the farm, helping the farmer feel they were getting a good deal.

From this, the vet produced a report with clear, prioritised actions and a time frame of when the vet would revisit.

With this continual motivation from the vet and revisits, farms quickly saw results, meaning farmers were buying in to the visits – to a point where they often now telephone to book in.

Conclusion

Identifying and developing new areas to work with farm clients is exciting and rewarding.

Increasing vet engagement with youngstock care massively helps with farmer relations, and recognition of vet and practice expertise.

This can have a dramatic effect on farmers’ bottom line and exposure to new revenue streams.

Vet job satisfaction is high, meanwhile, as calf problems in particular can see a quick turnaround, with obvious improvements.

References

- Atkinson O (2015). Happy Heifers (learning from the Welsh Dairy Youngstock Project the keys to successful heifer rearing), BCVA webinar, http://bit.ly/2chSudU

- Beam AL, Lombard JE, Kopral CA, Garber LP, Winter AL, Hicks JA and Schlater JL (2009). Prevalence of failure of passive transfer of immunity in newborn heifer calves and associated management practices on US dairy operations, Journal of Dairy Science 92(8): 3,973-3,980.

- Tilling O (2014). Effective management of colostrum in dairy calves, Veterinary Times 44(42): 6-7.

- Weaver DM, Tyler JW, VanMetre DC, Hostetler DE and Barrington GM (2000). Passive transfer of colostral immunoglobulins in calves, Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 14(6): 569-577.

Meet the authors

Kathryn Hart

Job TitleOliver Tilling

Job Title