18 Nov 2025

Peter Orpin BVSc, FRCVS, Dick Sibley BVSc, HonFRCVS and James Hanks discuss the options of dealing with this issue in farm herds.

Figure 1. The relationship between host, pathogen and environment, using Johne’s disease as the example.

Common approaches to controlling infectious diseases in farm animal populations include surveillance to detect infected groups, diagnostic testing to identify infectious individuals, segregation or culling of high-risk animals and enhancing resilience through vaccination.

The “test and treat” approach has been successful in controlling diseases where effective vaccines or highly sensitive diagnostic tests are available. However, more complex diseases, such as bovine tuberculosis (bTB) and Johne’s disease (JD), remain difficult to control due to epidemiological challenges including latency, anergy, lower test sensitivity, environmental persistence and wildlife reservoirs.

Instead, these complex diseases are often controlled by the “test and cull” approach, but its long-term effectiveness and sustainability is governed by the sensitivity of diagnostic tests (including their ability to detect latent or dormant infections), the economic viability of culling, and coordinated risk management. Moreover, effective control of these diseases requires farmers to go beyond testing and treatment, placing greater emphasis on preventing new infections via robust biosecurity and bio-containment measures.

The most significant driver of disease is the risk of disease entry and spread. If these elements are overlooked, the disease’s reproductive value (R value) has the potential to exceed the on-farm disease controls, so the disease level remains unchanged or increases (Orpin and Sibley, 2014).

The principles of controlling infectious diseases can be illustrated using the host, pathogen, environment model. The aim is to optimise the environment, maximise the resilience of the host and minimise pathogen challenge; for example, within JD control, the aim is to protect the newborn calf from infection from adult cows and particularly the dam (Figure 1).

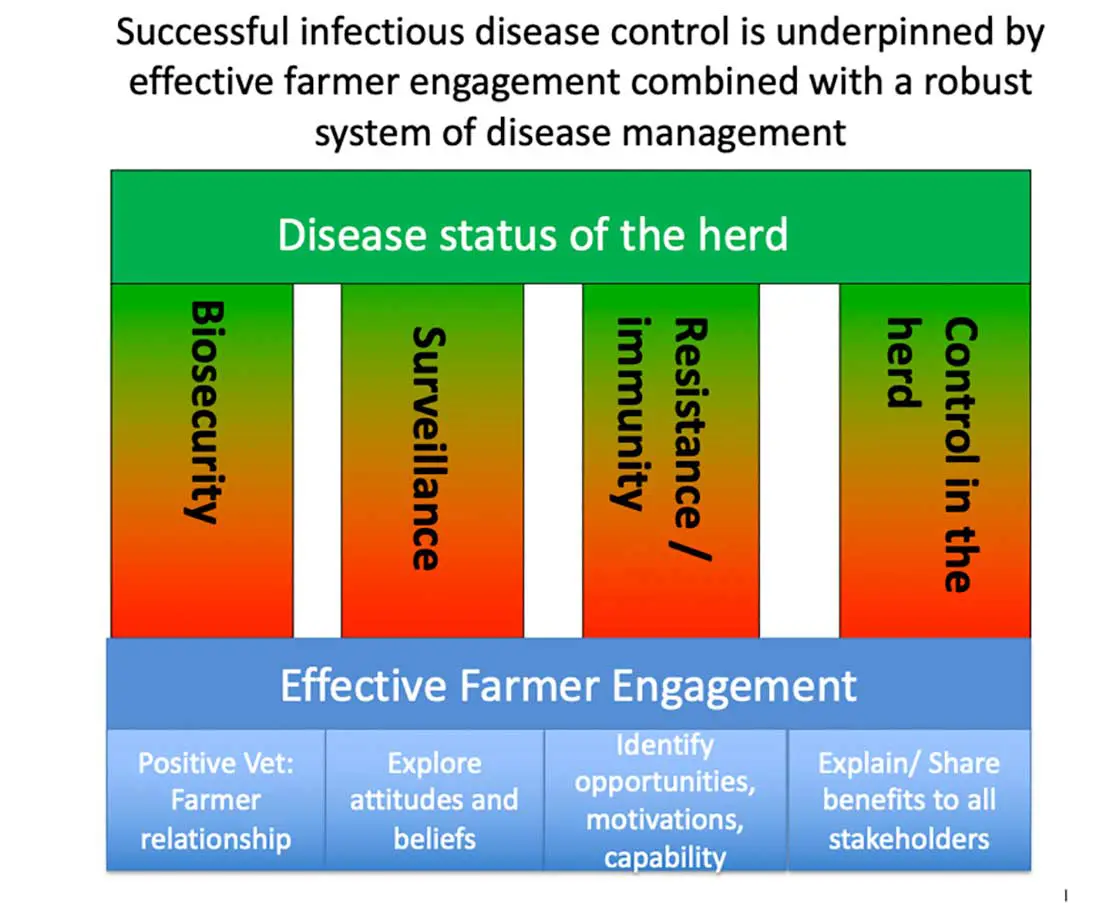

Herd-level disease status is determined by the four pillars of disease control: the risk of disease entry, disease surveillance quality, host resilience and the effectiveness of the control plan (Figure 2; Orpin et al, 2012; Sibley, 2024). Moreover, for disease control to be sustainable, veterinary advisors require a full understanding of farmer motivations, aspirations and resources. Farmer engagement with JD control is not uniform and varies depending on their attitudes and beliefs, practical challenges, vet-farmer relationship, industry drivers and scheme design (Orpin and Sibley, 2024).

The National Johne’s Management Plan (NJMP), which is ran by the Action Group on Johne’s, considered these pillars of disease and designed a framework, which maximises farmer engagement. As a result, farmers and JD advisors, along with processors and retailers, have taken ownership of JD control.

Sharing of costs and benefits incentives between farmers, vets and milk processors has led to widespread adoption, with more than 95% of dairy farmers involved within a commercial framework (Orpin et al, 2022).

Schemes that are centrally driven and funded frequently fail, as the benefits, ownership and costs are not aligned, and a restrictive programme is simply imposed upon the farmer often with inadequate explanation.

So, the farmer sees disease control as an imposition rather than a solution.

The NJMP is built upon the concept: “Know your Johne’s disease risk. Know your Johne’s disease status. Create a Johne’s disease management plan”; therefore, risk assessments are vital to JD control.

JD-related risk assessment data from 371 UK dairy herds, which used the Myhealthyherd application from January 2022 and December 2024 highlighted that 45% of herds had introduced cattle in the past five years; 60% of herds were not identifying high-risk offspring for segregation; and 33% of herds were not clearly identifying high risk adult cows (unpublished data). Compared to risk profiles from 2012 (Sibley and Orpin, 2012), substantive reductions have been noted in milk and colostrum transmission risks, but many risks in more important areas (cow to calf) remain as structural blocks to disease improvement in many herds.

Risk assessments are inclusive, low cost, informative and highly engaging. They help farmers identify weaknesses in their current control plans and encourage collaboration with their vet to develop a tailored approach. The outputs of a risk assessment directly shape the choice of surveillance and control strategies, ensuring the resulting on-farm disease control plan is bespoke, valued, shared and effective. Unlike surveillance-based programmes, which are retrospective, risk assessments are predictive and can be implemented before surveillance begins; hence, their place within the NJMP framework.

Modern livestock systems have inadvertently increased the risks of infectious diseases; for example, the average dairy herd size has increased by 2.5 times from 75 cows in 1996 to 175 cows in 2024 (AHDB, 2025). Expanding herds often purchase blocks of land away from the main farm. This magnifies the risks of disease introduction, since the original herd is likely to have boundaries with multiple farms with variable levels of immunity to a multitude of pathogens. These issues are particularly prominent in bTB control (Skuce et al, 2012).

The practical reality of removing all infected cattle in large herds using tests with relatively low sensitivity, but where transmission rate is high, is problematic; therefore, methods to reduce within herd spread must be found to increase the effectiveness of disease control.

The success of the “test and cull” methodology is dependent on the new infection rate being effectively controlled alongside the removal of the heavily infectious cows, as these animals pose the pathogen challenge and risk of transmission. Again, using JD as an example, small to medium sized herds with well-managed outdoor calving have successfully controlled JD using the “test and cull” approach (Figure 3). But this approach is not feasible in large intensive herds, as the risk of transmission and subsequent R0 will be too high.

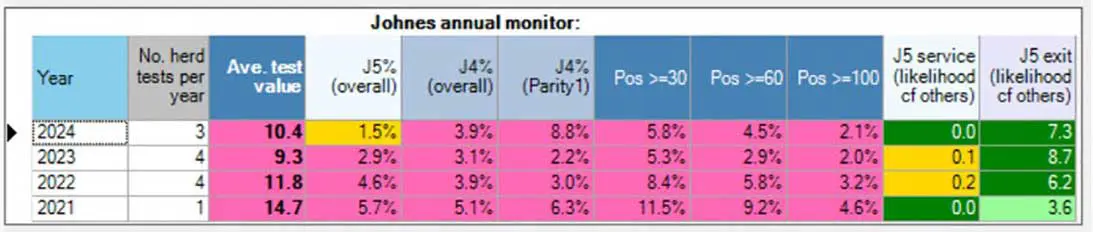

In autumn 2023, the National JD Tracker Database was developed through a collaboration between Dairy UK, PAN Livestock Services and the milk recording organisations (National Milk Records and Cattle Information Service). The database contains milk recording and milk ELISA data from approximately 2,750 herds per year, which test three to five times per year. The purpose of the database is to track progress of control at farm, practice, processor and national level, and to provide insights into the progression, persistence and management of JD.

This dataset has highlighted the relationship between the milk ELISA average test value (ATV) and J4 percentage (new detection rate/index case), since 76% of the herds that were in the worst quartile for ATV were within the worst quartile for J4 percentage. Herds in the worst quartile for ATV have a J4 percentage six times higher than herds in the best quartile for ATV (0.46% versus 2.88%; unpublished data).

Crucially, as shown in Figure 4, these parameters, along with other JD tracker parameters, are available to farmers and their JD advisors, and highlight if the chosen JD control strategy is effective. This evidence reinforces that the top priority for effective infectious disease control must be preventing new infections.

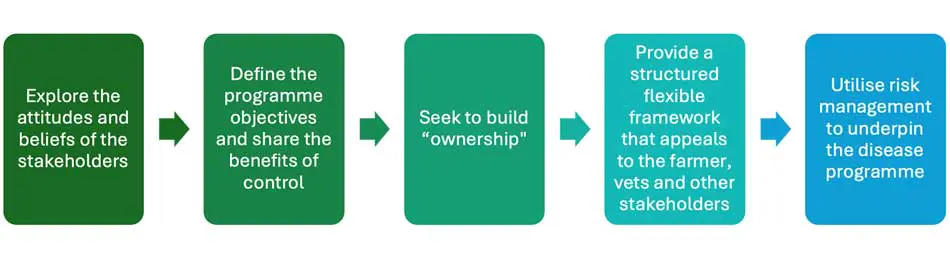

Explore the attitudes and beliefs of the stakeholders. When developing a disease control programme, it is essential to first explore the attitudes and beliefs of all stakeholders. Importantly, when working with farmers, consider their learning type (Ritter et al, 2016). Work with the proactivists first and then seek to tackle the unconcerned group that are yet to prioritise disease control.

Define the objectives of the programme and share the benefits of control. Once attitudes are understood, clear objectives must be defined; for example, whether the goal is eradication or acceptable control, as the resources and commitment required differ greatly. Importantly, farmers’ individual priorities, available resources, and motivations must be considered, with costs and benefits shared fairly among all parties to ensure long-term sustainability.

Seek to build “ownership”. Utilising education, peer to peer learning, social norms and coaching approaches encourages the farmers and other stakeholders to take ownership of the disease. The aim is to expand the population of people that believe and see the importance of control.

Provide a structured flexible framework that appeals all stakeholders. The management of dairy herds differs widely, so to maximise engagement, infectious disease programmes need to be flexible, such as the NJMP, and avoid the “one size fits all” narrative.

Utilise risk management to underpin the disease programme. Minimising transmission is key to disease control, so examine how the R0 be most effectively reduced (Sibley, 2024).

Substantive progress has been made with control of bovine infectious diseases. Early gains were achieved with vaccination.

However, if the progress is to be achieved with those more challenging, such as bTB and JD, a different emphasis is required.

Renewed approaches could focus on improved communication training for veterinarians; continued farmer engagement; increased use of predictive risk assessments; more precise testing methodologies; and the use of inclusive, practical disease programmes which deliver gains for all stakeholders.