8 Jan 2021

Jonathan Hobbs discusses ways of “getting it right” to reduce perinatal mortality, and improve cattle health and welfare.

Parturition is a risky time, both for mother and calf – and while not all risk can be removed, significant scope exists for improvement.

Perinatal mortality – often defined as the loss of a full‑term calf within 0 to 48 hours of calving, where the calf died before, during or after calving irrespective of the circumstances or cause of death – is the easiest metric to assess parturition outcome and welfare.

Perinatal and neonatal mortality is especially harmful in the suckler herd, where the entire system relies on a cow rearing one calf per year. Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) figures estimate the total cost of production for suckler herds at between £450 and £800 per cow per year; if a calf dies at or around calving this is a significant economic loss (AHDB, 2017). It also has a significant impact on the dairy sector, with the loss of future genetics.

The often-quoted target figure for perinatal mortality in suckler herds is lower than 2%, yet it appears this target is rarely met (Caldow et al, 2005). A recent study in Orkney found an average perinatal mortality rate of 5.1% in suckler herds (range 1.6% to 12.4%; Norquay et al, 2020). This is comparable to dairy herds, where the majority of studies report an incidence of between 5% and 8%, with some herds experiencing 20% (Mee, 2011; 2013).

Room for improvement clearly exists when it comes to this subject – and this article summarises the main areas requiring focus.

The major causes of perinatal mortality relate to dystocia caused by fetomaternal disproportion. This results from either direct fetal oversize, a small or abnormally shaped internal pelvic area in the dam, or a combination of both.

Careful selection of bulls before the preceding mating period, either for natural service or AI, is the first step in mitigating the risk of direct oversize. Estimated breeding values should be sought and the bull proof examined, paying particular attention to direct calving ease. This predicts the ease with which a calf by any particular sire will be born.

Maternal calving ease should also be noted if the farm is planning on keeping its own replacements for future breeding. This predicts the ease with which a daughter of the sire being reviewed will give birth herself – in other words, how the calving situation is likely to look on the farm in three or more years’ time.

Pelvic measurement of heifers prior to breeding allows for an assessment of their breeding viability. One in 20 heifers is reported to have too small a pelvic area or an abnormal pelvic shape; by identifying these animals, they can be removed from the herd and fattened.

This will reduce the incidence of dystocia on farm, which may otherwise require a caesarean to resolve, or lead to the death of both calf and dam if an overzealous attendant was to excessively pull the calf and get it “locked”.

Pre-breeding assessment of heifers, including the measurement of pelvic area, presents a good opportunity for vets to positively engage with their clients.

The vast majority of fetal growth occurs in the final trimester of pregnancy – ensuring pregnant animals do not receive excessive nutrition at this time is key.

Maintenance energy requirements for a 650kg cow are approximately 75MJ to 80MJ of metabolisable energy (ME) per day, with every one litre of milk production requiring an additional 5MJ ME/day.

It is only in the final two months of pregnancy that energy requirements to meet the demands of the growing calf are significant, equating to an additional approximately 25MJ ME/day above maintenance. Therefore, a 650kg dry cow only requires about 100MJ to 105MJ ME/day.

It is easy for the diet to exceed this energy requirement, especially when wanting to maximise dry matter intake (DMI) to reduce transition problems, particularly in dairy cattle.

Excessive energy intakes at this time will result in excessive growth of the calf in utero, but is also likely to result in a gain in body condition score and fat being laid down in the internal pelvic area, leading to a narrower birth canal and dystocia.

Fat cows are also more likely to suffer from uterine inertia, reduced DMI around calving and metabolic issues, and preceding other harmful events, such as retained fetal membranes (RFM), metritis, endometritis and displaced abomasum.

Careful dietary management, together with body condition score assessment and regulation, is crucial.

Trace element status – particularly that of iodine and selenium – should also be considered. Deficiencies in both has been shown to result in a range of conditions, including protracted labour (bradytocia) and uterine inertia, stillborn calves or weak-born “dummy calves” that often fade and die within a few days of birth, and a higher rate of RFM.

Widespread differences exist in the trace element status of farms across the UK and it would be prudent for vets to be aware of the specific situation within their locality. Trace element testing and interpretation can be problematic and is beyond the scope of this article, but veterinary laboratories will be able to provide support through this minefield and further resources are widely available.

Supplementation, if required, can be provided by a number of routes, including topical treatments, injectables, oral drenches or oral bolus. Each has pros and cons – from variations in persistency of action to,ease of use, cost and so on – and these should all be considered before recommendations are made.

It is important to provide adequate time before intervening. Stage one of labour (dilation of cervix) can take three to six hours, with stage two (expulsion of the fetus) taking one to three hours for cows, but five to six hours for heifers.

It is common for attendants to jump into assisting too soon, resulting in attempting delivery before the soft tissues of the birth canal have fully dilated. This can lead to both physical trauma for the dam, such as a torn cervix, as well as to the calf – for example, broken legs, vertebrae or ribs. The risk of inhalation of amniotic fluid by the calf, hypoxia and death is also increased in these instances.

Conversely, it is important to not to wait too long before intervening. The key point with stage two is that regular progression occurs – a heifer can happily take six hours to expel the fetus; however, if it is presented normally with feet visible at the vulva and these do not move for one to two hours, a problem is likely present that requires investigating.

Bradytocia is known to decrease fetal oxygenation because blood vessels to the maternal portion of placentomes cross the myometrium; therefore, with uterine contractions, vascular resistance is increased. This restricts blood flow to the calf – and the longer this persists, the greater the risk of hypoxia.

Furthermore, transvaginal manipulation of the calf stimulates further oxytocin release, leading to an increase in contractions, further enhancing the risk of hypoxia.

In cases of bradytocia, or where significant transvaginal manipulation is required, it is perhaps prudent to administer clenbuterol to the dam to try to reduce fetal hypoxia.

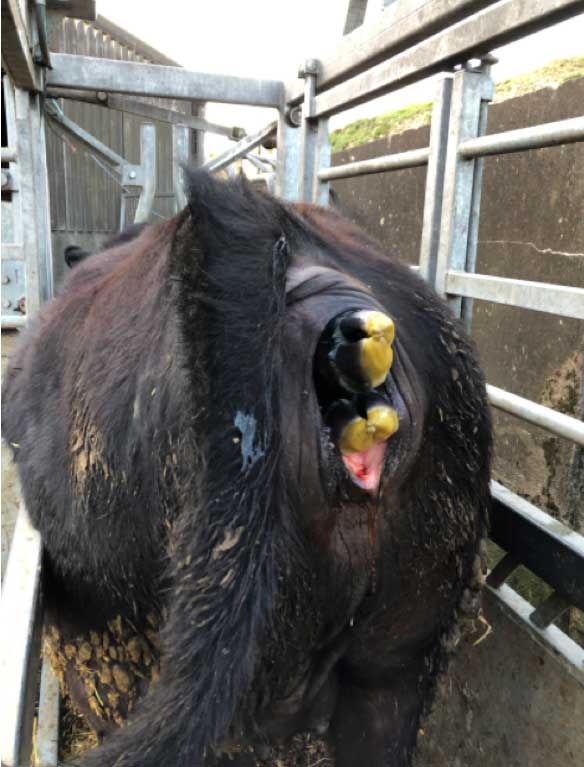

In the event of dystocia and fetomaternal disproportion, a caesarean should always be considered. Making this decision earlier, before attempting prolonged parturition and applying excessive traction, significantly improves outcomes. Clues pointing towards fetomaternal disproportion include large feet crossing at the vulva (Figure 1), an inability to pass a hand over the calf’s head when within the pelvis, a swollen oedematous head and tongue, and non‑progressive labour with no abnormality of presentation.

It is also prudent to ask the farmer how other calvings have proceeded to help make a decision as to whether a caesarean is required. Questions to ask include:

Where strong evidence exists of inhalation of amniotic fluid, it is wise to lift the calf over a gate (or similar) and suspend the calf by its hindlegs for approximately one minute, with the head dependent to allow drainage of any amniotic fluid from the upper and lower respiratory tract.

This technique causes debate among vets, with some feeling this is counterproductive due to the pressure of abdominal organs on to the diaphragm restricting thoracic volume. However, it has been shown to be beneficial in calves born by caesarean, providing it is done for no longer than 90 seconds (Uystepruyst et al, 2002).

After suspending the calf, it should be placed in sternal recumbency (Figure 2) and not lateral, which would otherwise compress the dependent lung lobes.

While in first opinion practice diagnosis of hypoxia via assessment of blood gasses is unrealistic, it should be suspected if the calf will not spontaneously reach sternal recumbency within 15 minutes, has poor reflexes and/or poor muscle tone.

An IV bolus of 50ml to 100ml of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate is often found to be useful, but must not be administered if the calf is not breathing unassisted, as this will only make the respiratory acidosis worse.

Supplemental oxygen, if available, for 5 to 10 minutes is also beneficial.

The phrase “survive to five” has been coined as 95% of losses within the first hour after parturition occur within the first five minutes – in other words, if the calf survives the first five minutes then it has a much greater chance of survival (Mee, 2017).

Extended time to achieving spontaneous sternal recumbency has also been shown to decrease calf vitality. A duration of at least 15 minutes has a predictive value of 84% for non-viability and the time to sternal recumbency is significantly longer following forced extraction compared to other delivery methods (Schuijt and Taverne, 1994).

Moving to the dam, the significant (P = <0.05) risk factors for postpartum uterine disease include RFM, stillbirth, twins, dystocia and primiparity (Potter et al, 2010). Therefore getting parturition correct through the aforementioned steps will significantly improve subsequent fertility, as it is known endometritis increases the calving to first service interval, number of services per conception and calving to conception interval (Borsberry and Dobson, 1989).

Assuming a successful parturition and a live calf is born, the next step is umbilicus management (such as application of iodine) to prevent navel ill and subsequent sepsis, together with adequate colostrum provision.

As is reported ad nauseam, the “five Qs” of colostrum management should be observed:

Consideration should also be given to the environmental temperature, including housing and bedding if relevant, with regards to the thermal neutral zone of between 10°C and 26°C for a newborn calf. The lower critical temperature (LCT) rises from 10°C to 17°C when on bare concrete, and for several days of the year in the UK environmental temperatures are below the LCT of 10°C.

When any animal is below the LCT, additional feeding will be required as additional energy will be used to generate heat in an attempt to stay warm. Failing to provide this additional feed will result in reduced growth and/or increased disease.

Once through the first 48 hours of life, the neonatal period provides further risk to the calf, from common diseases such as diarrhoea. Regardless of the cause of diarrhoea, good hygiene is critical – as it is through the entire parturition process – and should be thoroughly reviewed when investigating outbreaks, in addition to questioning colostrum management and undertaking specific diagnostics.

Reaching a diagnosis is key so that we can correctly use additional tools in our armoury to prevent or reduce infection, such as vaccination.

This article barely scrapes the surface, but getting all these steps right will result in a significant reduction in the rate of perinatal mortality, leading to improved health, welfare and productivity on farm.