11 Nov 2019

Increasing incidence of abomasal disease in calves

Dominic Harrison, Mick Millar and Oliver Tilling discuss the clinical signs of this issue and five underlying risk factors that appear to enable its establishment.

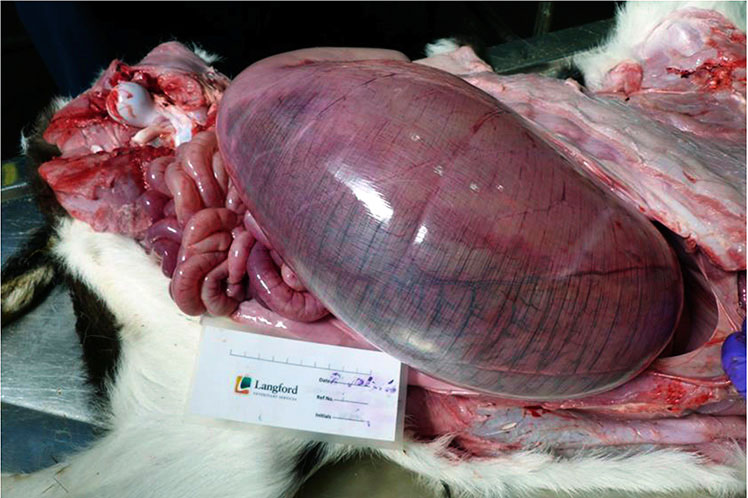

Figure 2. Abdominal bloat is a usual feature.

- The lead author was a final-year student at the time of publication.

Abomasitis is a sporadic disease predominantly affecting neonatal dairy calves younger than three weeks of age, but can be found in any ruminant.

The development of abomasitis is often preceded by abomasal bloat and ulceration. Calf mortality is greater than 60%, with death occurring within six hours in peracute cases or up to two days in less severe instances.

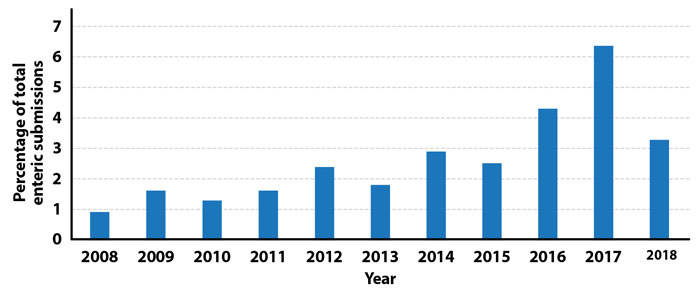

Over the past decade, Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis (VIDA) figures have shown a rise in preweaned deaths of dairy calves due to abomasitis and bloat. As a percentage of enteric submissions, abomasitis and abomasal bloat have increased from less than 1% in 2008 to nearly 6% in 2017.

In many of these cases, Clostridium species (Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens) and Sarcina-like bacteria have been identified. Both species are capable of toxin production and rapid fermentation.

Figure 1 shows the submissions of abomasal bloat and abomasitis not otherwise specified, as a percentage of each annual enteric submission (VIDA data). The increase in diagnoses of abomasal bloat and abomasitis from 2008-17 shows a need to address underlying aetiologies and alter management systems to prevent further increases.

Clinical signs

Development of bloat and abomasitis can occur rapidly (peracute cases within the first 24 hours of birth), so it is important to note the clinical signs to look out for.

Some clinical signs are common between abomasitis and bloat:

- depressed animal

- recumbent in housing

- reluctance to stand and feed

- reduced gut sounds

Others can be more specific and depend on the route the pathogenesis takes; abomasitis with or without bloat and ulceration.

Abomasitis

The inflammation and organ distention associated with abomasitis leaves the calf with clinical signs associated with pain and discomfort. Others can be more general markers of disease.

Among the more common clinical signs are:

- recumbency and abdominal bloat (Figure 2)

- dehydration

- bruxism

- salivation

- colic

- reduced gut sounds (due to inflammation and stretching of viscera)

- congested mucous membranes

- death

Calves affected in the early stages may present with malaise, reluctance to feed and a depressed state.

As more severe inflammation and ulceration occur, calves may show signs of pain, such as bruxism and bellowing.

Bloat

Due to the positioning of the abomasum on the ventral right side of the abdomen, severe cases of bloat can be seen as distinct bulging in this area. Reduced gut sounds can be observed and “sloshing” of contents can be heard on manual manipulation (ballottement).

Postmortem findings

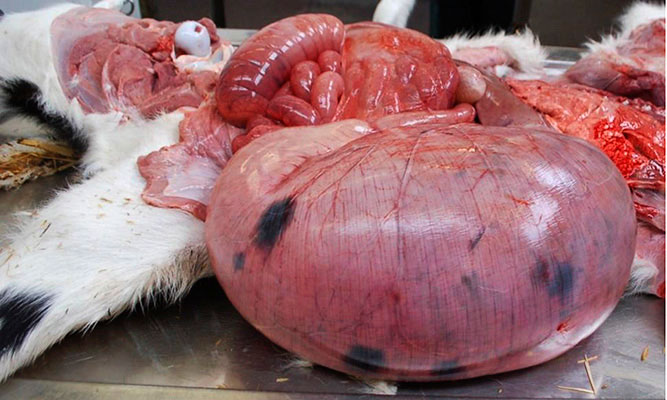

- The abomasum is usually markedly distended (Figures 3 and 4), unless rupture has preceded necropsy, and can be extremely reddened and haemorrhagic, with focal dark areas evident (distention of the abomasum can be antemortem due to bloat, or postmortem due to ongoing fermentation of abomasal contents by pathogenic bacteria).

Figure 3. Marked distension of the abomasum.

Figure 4. Marked distension of the abomasum. - Severe cases of bloat and abomasitis can lead to rupture of the abomasum and spilling of contents into the abdominal cavity.

- Focal to diffuse areas of darkening (in some cases, almost black – necrosis) on the abomasal mucosa (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5. Marked darkening and emphysema of the abomasal mucosa is commonly seen.

Figure 6. Marked darkening and emphysema of the abomasal mucosa is commonly seen. - Abomasal mucosal oedema and ulceration, possibly with haemorrhage/petechiation, and focal areas of emphysema (gas bubbles secondary to bacterial invasion). Occasionally, lesions can be localised (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. Lesions may occasionally be more localised.

Figure 8. Lesions may occasionally be more localised. - Brown fluid and clumps of undigested congealed milk contents in the abomasum. The abomasal content pH is usually elevated (higher than pH2 to pH4).

- Milk/feed contents in the rumen.

- Accompanying enteritis may be present, with relatively liquid small and large intestinal content.

Pathogenesis

Before abomasitis can develop, the correct environment must be present.

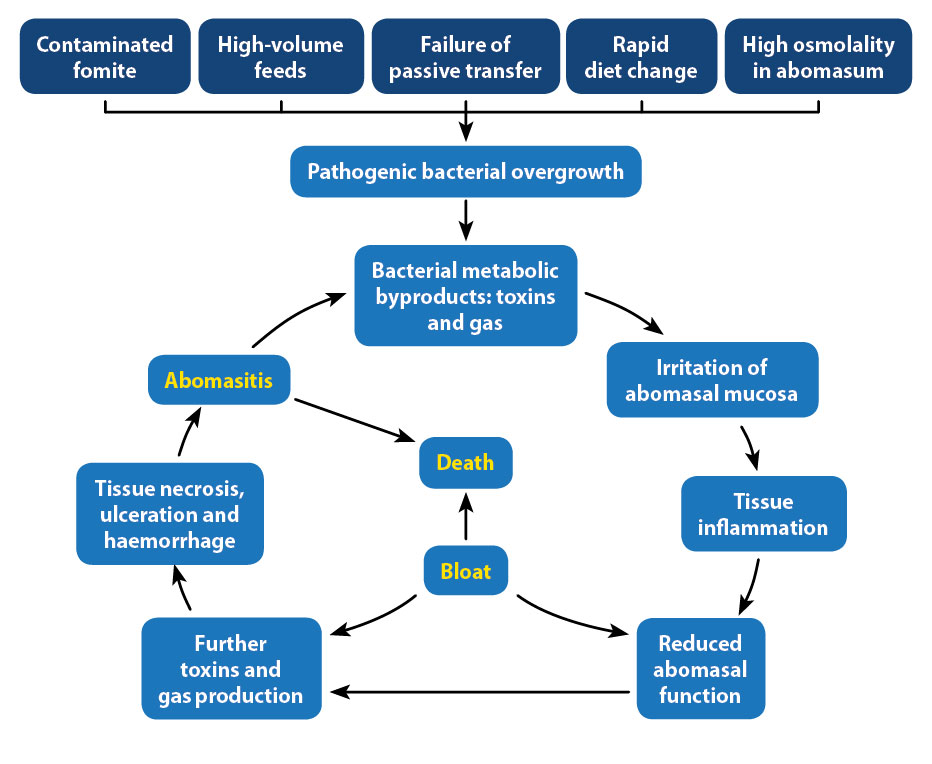

The irritation that leads to abomasitis is caused by toxins produced by Clostridium species and Sarcina-like bacteria. These bacteria require an environment rich in fermentable carbohydrate and a calf with a poor immune status to multiply. If these requirements are met, the pathogenesis takes a predictable and cyclical route – leading to the death of the calf:

- Entry of bacteria into the calf digestive system via contaminated fomite, such as soil, faeces or straw bedding.

- The presence of easily fermentable carbohydrates in the abomasum allows Clostridium species and Sarcina-like bacteria to replicate, leading to the production of gas and toxins.

- Bacterial toxins irritate the abomasal mucosa – leading to tissue inflammation, hyperaemia and oedema.

- Sustained irritation results in tissue necrosis, haemorrhage and decreased abomasal function (at this stage, the calf can die of sepsis, haemorrhage or dehydration if the abomasitis is severe enough).

- Reduced abomasal emptying and eructation allows buildup of bacterial fermentation products – particularly gaseous carbon dioxide – leading to abomasal bloat.

If left untreated, the cycle of tissue inflammation and/or bloat, bacterial gas and toxin production will continue until the calf dies.

Why are normal defences failing in these calves?

Five main underlying risk factors appear to exist that enable the establishment of pathology.

High osmolality inside the abomasum

Milk replacers form a valuable and easy way of ensuring the calf calorific intake is met. The energy content of milk replacers is significantly higher than that of the equivalent volume of maternal milk, resulting in a high abomasal osmolality.

If the energy content of the replacer exceeds that of the metabolic requirement of the calf, large amounts of easily fermentable carbohydrates will remain in the abomasum. This environment is ideal for the rapid growth of bacteria.

Studies have shown high osmolality inside the abomasum leads to reduced emptying and increased disease occurrence1.

High-volume feeds

Large volumes can overwhelm the abomasal ability to digest contents and prolong its emptying time.

For low-frequency (once or twice daily) feeding to meet the metabolic requirements of calves, they must provide a higher volume of feed. These high-volume feeds distend the abomasum, slow emptying time and provide ideal carbohydrate-rich environments for pathogenic bacteria to proliferate.

Insufficient colostrum and failure of passive transfer

The importance of colostrum cannot be overstated. For a neonatal calf to mount a defence against invading pathogens, it must have sufficient levels of maternal antibodies – in both the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract and the blood2.

For sufficient levels to accumulate in the calf, an ideal concentration of 50g/L of IgG should be present in the dam’s colostrum and the calf must receive sufficient volumes to achieve 10g/L IgG in its bloodstream2.

Rapid diet change

The rapid movement from milk to milk replacer diet has been linked with the development of abomasitis and bloat.

Milk replacers have high quantities of bioavailable carbohydrates and proteins; while these are important for calf growth, it takes time for the abomasum to adapt to the new diet.

Contamination of feeding tubes, buckets, bedding and other materials increase the likelihood of ingestion of these pathogenic bacteria by the calf.

Other factors

Other factors that may contribute to the development of abomasitis and bloat include:

- housing

- weather

- foreign bodies, such as trichobezoars and straw

- mineral deficiencies (copper and selenium)

- stress:

- overcrowding

- isolation

- people/machinery

- heat/cold

- limited access to water

- other disease processes, especially diarrhoea

Figure 9 is a diagram showing the five most common aetiologies leading to the development of bloat and abomasitis.

Prevention

Prevention of abomasitis centres on management of the risk factors.

- Lower the osmolality in the abomasum: Meeting the energy requirements of the calf and not providing excess fermentable carbohydrates in feeds. Not only will high-concentrate feeds provide an ideal (high osmolality) environment for pathogenic bacteria to colonise, but it will also cost more to the producer. Providing continuous access to clean, fresh water means calves can easily dilute abomasal contents and, therefore, reduce osmolality while maintaining good hydration status.

- Increased frequency of feeding and decreased volume: Ideally, calves should be fed three to four times a day – this will ensure volumes inside the abomasum do not cause distention and are emptied more frequently.

- Colostrum, colostrum, colostrum: Calves must receive sufficient levels of colostrum within the first 24 hours of life. Failure of passive transfer (less than 10g/L maternal antibodies) will lead to a stunted immunity and high susceptibility to infectious diseases, including abomasitis.

- Slow transitions: When substituting calves from milk-to-milk replacer, it is beneficial to slowly change the ratios until calves are only on the replacer.

- Hygiene and environmental contamination: Feeding tubes should be thoroughly disinfected before and after tubing any animal. Clostridium species are ubiquitous in the environment and can easily be transmitted via soiled fomites. Introduction of these bacteria into an immunologically naive calf highly precludes to development of abomasitis.

Treatment

If presented with a sick calf showing the clinical signs of abomasitis, prognosis should be guarded. However, a few steps can be taken to increase a calf’s chances of survival:

- Correction of dehydration levels should be done with IV fluids.

- Oral and systemic antibiotics (penicillins) for treatment of Gram-positive Clostridium species and Sarcina-like bacteria.

- Skip one milk feed/don’t feed for 12 hours. This is to stop adding more fermentable carbohydrate into an already compromised, high-osmolality environment. Note that water should be available to sick animals at all times.

- Sedate and roll the calf on to its back, then use a 16G needle or catheter to puncture the abdomen and allow gas to escape from a bloated abomasum (much like correcting a left-displaced abomasum using the Grymer-Sterner technique) in severely bloated cases.

Summary

Abomasitis and abomasal bloat share common steps in their development:

- Excess fermentable carbohydrates allow pathogenic bacterial colonisation.

- Fermentation and toxin production by pathogenic bacteria.

- Irritation from the toxins leads to damaged mucosa, or abomasitis with or without ulceration.

- Bacterial fermentation leads to large volumes of gas production.

- Distention of the abomasum reduces functionality and contents remain in the lumen.

- Eructation ability is compromised due to reduced abomasal function, leading to an increased severity of bloat.

- Calf death due to a combination of haemorrhage, sepsis, dehydration, malnutrition and bloat.

The five main factors that can predetermine abomasitis are:

- high abomasal osmolality

- large-volume feeds

- insufficient colostrum intake

- rapid diet change

- contaminated fomites

- With regards to prevention and control:

- Make sure oral rehydration therapy and milk replacers are at the correct concentration for the size of calf.

- Avoid feeding large bolus of milk/milk replacers, especially by oesophageal tube.

- Ensure adequate colostrum intake in the first 24 hours of life and avoid the use of pooled colostrum.

- Gradually change diets from milk to milk replacer.