14 Dec 2020

Innovations in udder health

Phil Elkins discusses this key area of disease prevention, as well as updates in treatments and preventive strategies.

Mastitis control has been a mainstay of veterinary input to herd health for decades, and certainly since the conception of the “five‑point plan” (Panel 1) in the 1960s.

- Treat and record clinical cases.

- Post-milking teat disinfection.

- Dry cow therapy.

- Cull chronic cases

- Milk machine maintenance.

Despite years of involvement and research, udder health continues to be a key production disease of public, farming and veterinary interest.

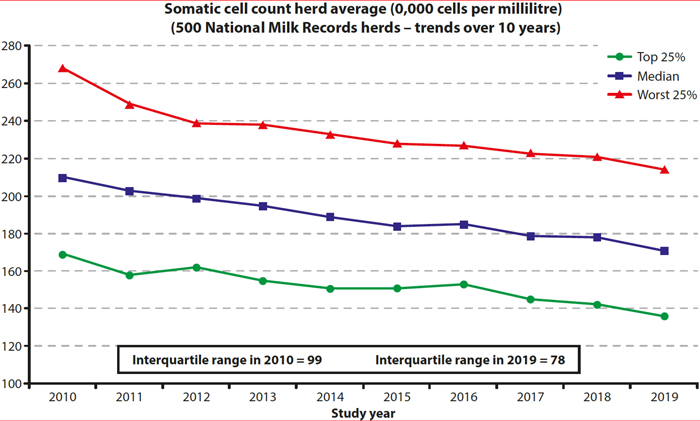

According to the most recent cohort study of 500 herds, carried out by National Milk Records, more than 25% of herds had an average somatic cell count (SCC) greater than 200,000 cells per millilitre – representing not only potential milk price penalties, but also loss of production1.

While this represents a significant improvement over the past 10 years (Figure 1), significant scope still exists for improvement on many units.

A similar picture is shown when looking at clinical mastitis, with the best performing 25% of herds recording clinical mastitis rates below 18 cases per 100 cows per year, but, by contrast, the worst performing 25% of herds recording more than 48 cases per 100 cows per year.

This shows significant scope for veterinary involvement in targeting improvement in rates of both clinical and subclinical mastitis.

While this article is about innovation in the field of udder health, it is important to remember the basic principles of mastitis control have not significantly changed in recent times.

The aforementioned five‑point plan was designed to combat contagious mastitis pathogens and is widely accepted as a successful blueprint for these cases. As contagious mastitis control improved – and intensification of production has occurred – a shift towards environmental pathogens and patterns of mastitis have been seen.

The author’s pragmatic approach to environmental mastitis is quite simple – well‑managed, clean cows in an appropriately functioning parlour are unlikely to get mastitis (Figure 2).

Having said little change has been seen in the basic principles of mastitis control, that does not mean vets do not, as advisors, have an increasing armoury within their reach to help improve udder health.

The following review is not comprehensive, but intended to be thought-provoking regarding the breadth of tools vets can use to control mastitis, together with some recent research.

Genomics

Mastitis and SCC are two conditions that have a low heritability – the proportion of natural variation seen within the population that is a result of genetic diversity. Estimates place the heritability at between 1% and 42%2. Despite having a relatively low heritability, the advantages of breeding for these traits can be financially significant.

In the top 20 bulls for mastitis and SCC resistance, only 3 have undergone the traditional UK daughter proven process. The remainder have been identified using genomic testing – looking for gene segments associated with phenotypic conditions. Although the reliability may be higher from proven bulls, genomics offers a wider diversity of bulls, with generally more positive traits. In fact, the top 150 bulls on Profitable Lifetime Index are all genomically tested and yet to have a UK daughter proof.

Incorporating genomically tested bulls into breeding plans should now be commonplace with large benefits. With the widespread use of sex-sorted semen in many cases leading to a surplus of replacement heifers, genomic testing of heifers on farm can be a rewarding exercise – ensuring the animals most suited to the herd become the source of the next generation will enhance the speed of genetic progress over blanket heifer breeding plans.

This is a simple procedure that can be cost‑effective to implement.

Parlour testing

As alluded to earlier, an appropriately functioning parlour is important for control of mastitis of an environmental origin. Milking machine maintenance is also part of the five‑point plan for control of contagious pathogens of the udder.

The milking machine, however, should not just be seen as a risk factor for disease. It is also an opportunity for optimisation of the milk harvesting process.

The milking machine is as integral to the processes on a dairy farm as any equipment, yet is often not performing to the best of its ability, either due to inappropriate setup or lack of maintenance. Optimised milking machines will lead to efficiency of milk harvesting from the udder, in a way that is considerate of the teats – leading to no short‑term or long-term negative effects on the teats.

A number of pieces of equipment are now available to assist vets, and other consultants, to better assess the performance of the milking machine; however, vets can take a number of measures to assess the impact of milking on the teats.

Teat scoring is a simple exercise that will quantify the number of short‑term, medium‑term and long‑term changes to the teats:

- Short-term changes include teat discolouration, oedema and firmness of the teat end or barrel, ringing of the teat base and openness of teat orifice.

- Medium-term changes occur over a few days, and include changes in teat skin condition and petechial haemorrhages on the teats.

- The main long-term change – which takes prolonged time to develop and, equally, regress – is hyperkeratosis of the teat end.

All of these changes indicate inappropriate pressure on the teat barrel or teat end, and represent a risk factor for mastitis, as well as, in some circumstances, being painful and creating an aversion to the milking process.

Once a potential issue has been identified, this would require further investigation to determine an appropriate course of action.

Equipment is now commercially available that can assess a multitude of parameters associated with the milking process – including teat end vacuum, duration and ratio of the phases of milking, proportion of bimodal milk let-down, time to peak flow, two-minute milk yield, total milking time, milk flow at take-off (when automatic cluster removal is installed) and duration of overmilking at a quarter level.

This list is certainly not exhaustive, but it is clear to see a wealth of information can be gained regarding the interaction between cows and the milking machine. This is rapidly becoming a “specialised” area of interest.

For vets wanting to engage more in this area, two routes for involvement exist – vets can attend training courses in both the equipment and the interpretation of the results, or they can look to engage with third-party businesses that specialise in providing these services to farm.

In the author’s experience, both routes are viable, but increasing the familiarity with the equipment and interpretation of results takes a commitment in time and numbers – bringing in an external expert to tackle these issues can lead to improvements in animal health while consolidating the relationship with clients.

Foremilking

Udder health remains a key area for research within the dairy health field. In the past quarter, 28 articles have been published in the Journal of Dairy Science that reference mastitis. One example of recent research concerns the role of foremilk stripping.

It is a legal requirement that milk from every cow is examined prior to the cow being milked for human consumption. This is to prevent the milking of a cow with grade one or above clinical mastitis (visible changes to milk) into the human food chain. However, it is the author’s experience that this is not universally applied.

The justification for not foremilking is frequently that it is a time-consuming process with little perceived benefit. As herd sizes increase, a number of changes happen – milking can become protocol‑driven and routine‑driven, individual animal milk changes can be rapidly diluted in a bulk tank and in-line milk filters at either a herd or individual animal level can be used as an indicator of the need for further investigation.

This approach leaves concern for both public confidence in dairy products, and animal health and welfare.

A recent study showed many of the reasons for not foremilking are not justified. The results of this study showed that foremilking, as an extra stage in a typical milking routine, showed a number of benefits due to prolonged and consistent tactile stimulation of the teats: shorter milking on times (reduced milking times for each cow), higher two-minute milk yield, lower length of time in low milk flow and a lower susceptibility to short-term machine‑induced changes3.

This information, together with the early detection of mastitis, can be used by vets to reinforce the requirement for foremilking as part of an effective milking routine.

Vaccines

Relatively recently, two vaccines have been brought to the market with a clear role to play in the control of mastitis.

One vaccine – a biofilm adhesion component of Streptococcus uberis – was licensed two years ago. The vaccine schedule involves three doses – two pre-calving and one post‑calving – to offer the best protection in early and mid lactation. Trial work demonstrates a reduction in the incidence of mastitis caused by S uberis of 52.5% (P=0.017)4. The author’s experience of the vaccine on UK farms is limited, but the early case work looks promising.

The second vaccine has been in production for longer, and includes antigens from Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase‑negative staphylococci and Escherichia coli. This vaccine has been shown to reduce the now‑famous reproduction ratio of S aureus infections by 45%, as well as a reduction in the severity of mastitis cases caused by S aureus5. It has also been demonstrated in UK situations to reduce the severity of clinical mastitis associated with E coli, as well as a general, non-specific increase in milk yield. This represented a return on investment for farmers of 2.57:16. This vaccine may have a role to play in herds with significant S aureus infections, or where severity of mastitis – in particular with regards to E coli – is a concern.

Therapeutics

The treatment of clinical mastitis has deliberately been left to the end of this article.

The key role of vets in udder health is in the prevention of both clinical and subclinical mastitis. However, it is unlikely to ever be 100% successful at this.

While some innovation has occurred with the increasing uptake of culture‑based therapeutics, in the author’s opinion the biggest change in the therapeutics of mastitis has been a shift in the mentality of treatments – driven in a large part by the drive to ensure, as a profession, antimicrobials are used responsibly, vets are increasingly considering the choice of treatment for mastitis more carefully.

Obviously this year that has been subject to some wide‑reaching product outages; however, a number of principles are becoming more common: for both lactating and dry cow therapy, antibiotic choice is being tailored towards most appropriate use.

The use of antimicrobials, and choice of product, has come under increasing scrutiny from vets, with consideration placed on whether the product is broad or narrow‑spectrum – with broad‑spectrum products selected for those cases where causal pathogen is equally likely to be Gram‑positive or Gram‑negative; and narrow spectrum where the causal pathogen is more likely to be Gram‑positive, as demonstrated by chronicity, herd patterns and supported by diagnostics.

Equally, the use of systemic antibiotics for mastitis is coming under increased scrutiny, with an increasing body of evidence that their effects in treating mastitis are limited.

As a profession under a degree of scrutiny, vets need to ensure – when dispensing antimicrobials for use on farm – the product choice and treatment protocols are justified.

Conclusion

While mastitis and udder health continue to form a cornerstone of vet advice on farm, and the principles of mastitis control remain the same, a number of new and different considerations exist to continue to evolve the service offered by vets in this area.