11 Sept 2017

David Rendle discusses measures he considers should be taken to manage obesity in horses, in the first of a two-part article.

Figure 1. Obesity is a major risk factor in the development of laminitis.

Laminitis is one of the most common conditions treated in equine practice and has a profound impact on equine welfare – it causes severe pain, has a high rate of recurrence and may necessitate euthanasia.

While laminitis is a common endpoint to a number of pathophysiological mechanisms, the importance of endocrine dysfunction in the development of laminitis is accepted, with the majority of cases of “pasture-associated” laminitis being attributed to equine metabolic syndrome (EMS) or pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID)1.

Testing for PPID is second nature to most equine vets and a positive diagnosis is satisfying, as dopamine agonists are effective in controlling the pituitary dysfunction. However, those not diagnosed with PPID are at risk of being overlooked because the management of EMS is more challenging and potentially less rewarding. Some horses with PPID will have concurrent EMS and the contribution the latter makes to the development of laminitis in these cases may also be overlooked, as highlighted by the number of cases with well-controlled PPID that continue to suffer from recurrent laminitis (Rainbow Equine Lab, unpublished data).

EMS is a complex syndrome of obesity (general or regional), insulin dysregulation, hypertriglyceridaemia and increased circulating adipokines associated with the development of laminitis (Figure 1)2. In those with a genetic predisposition, insulin dysregulation and hyperinsulinaemia are driven by obesity and may ultimately lead to the development of laminitis. Adiposity and tissue insulin sensitivity are negatively correlated in horses3, and insulin dysregulation is associated with the development of laminitis4.

Management of obesity is, therefore, considered central to the management of laminitis risk. In addition to increasing the risk of laminitis, obesity in horses is associated with strangulation of the intestine, hyperlipaemia, altered thermoregulation, altered reproductive cycling, increased blood pressure, reduced athletic performance, inflammaging, osteochondrosis and bad behaviour.

Reduction of obesity in horses with EMS (and PPID) has multiple benefits:

Management of obesity in horses is not straightforward and parallels are seen between horses and other species, including our own. This article outlines the management of obesity in horses, with a focus on obesity-related laminitis. Part one outlines specific measures that should be taken to manage obesity, while part two focuses on monitoring, ensuring compliance and the use of pharmaceuticals if cases fail to respond to management alone.

Fundamental to any weight-loss programme is for the owner and, ideally, all those involved with the care of the horse, to recognise it is overweight, and appreciate what the horse should look like. Owners often have a distorted perception of how their horse should look and are poor at accurately assessing its body condition score. Owners must be fully cognisant of what needs to be achieved and the psychological difficulties they will face for any weight-loss programme to be successful (discussed in part two). In the management of obesity in humans, success rates are higher if the patient understands, and has ownership of, his or her weight-loss programme5.

The horse’s diet, management and other health issues need to be assessed. It is important to establish how often the horse is turned out and how willing the owners would be to restrict or eliminate pasture turnout, and provide access to areas of non-pasture turnout. The owner’s willingness, and the horse’s ability to exercise, should be established as level of work may have a bearing on caloric requirements.

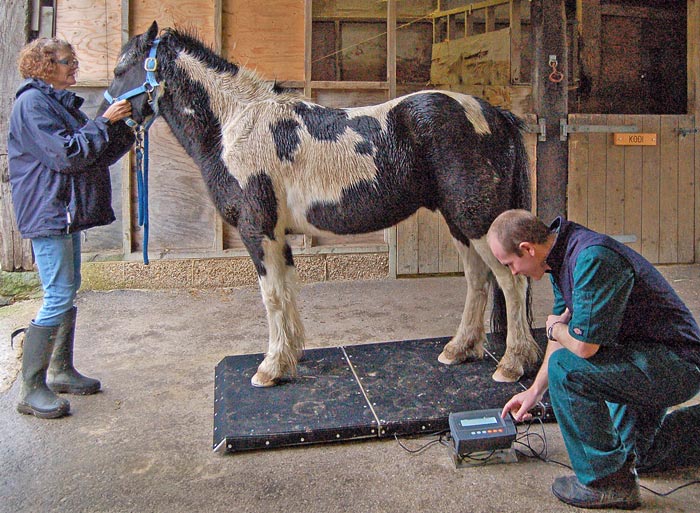

The horse’s weight should be determined or estimated using a validated weigh tape. The use of a weigh tape alone, without validation with a weighbridge, can lead to client underestimations in bodyweight – especially if regional adiposity is present, which can lead to a false sense of owner security. Portable weighbridges are extremely useful, but expensive (Figure 2). Weigh tapes provide a reliable substitute. Morphological characteristics should be recorded including:

Body condition score should be assessed, but considered of lesser importance than actual weight or morphological characteristics, as it has limitations when used in assessing UK native breeds6 and is very slow to change in response to reductions in bodyweight7. The morphological characteristics previously outlined will change before body condition score7, reassuring the owner progress is being made and providing him or her with encouragement to continue.

Once the baseline data has been established and recorded, a diet plan should be agreed with the owner and regular follow-ups scheduled at intervals of four to six weeks.

It is standard practice for obese horses to be maintained on a hay diet, with a vitamin and mineral balancer. A balancer is important to ensure sufficient protein and micronutrients are provided when forage is restricted, particularly if forage analysis has not been performed and if forage is being soaked. Cereals, oils and treats, such as carrots and apples, should be eliminated from the diet. The hay would ideally be analysed so its digestible energy content is known to be less than 12% non-structural carbohydrate (NSC) and, preferably, less than 10%.

Native grass hays and late cut hay with a higher ratio of stem to leaf will have a lower NSC content even if they have some seed heads. Although often assumed to have a higher NSC content, haylage often has a lower NSC content than hay made from the same grass – it is simply more palatable, so voluntary intake tends to be greater. If the quantity fed is restricted, haylage is a feasible alternative to hay and may be more suitable for horses with concurrent respiratory disease. Forage analysis is inexpensive (approximately £30); however, it is a route owners are often reluctant to go down and of less value if their hay source frequently changes.

An empiric approach is to feed hay at 1.5% of the horse’s bodyweight, which will correspond to 70% to 80% of what would be required to maintain current bodyweight. The distinction should be made between feeding dry matter or fresh weight; in the literature, recommendations are often made on a dry matter basis, while, in practice, fresh weight is far more useful. Most hays are 80% to 85% dry matter, so feeding 1.5% bodyweight of fresh weight would correspond to 1.28% bodyweight of dry matter.

The NSC content of UK hays is hwighly variable and, if the NSC content is unknown, the hay should be soaked. The effect of soaking can be as variable as the initial NSC content and, in one study in which hay produced commercially in the UK was soaked for 16 hours at 8°C, the reduction ranged from 6% to 54%, with a mean of 27%9. By contrast, in another study, soaking for 14.5 ± 2.1 hours resulted in a mean reduction of 50.1% NSC, with little variation between samples10.

Water temperature has a marked effect and soaking in water at 16°C for 1 hour has the same effect on sugar content as soaking at 8°C for 16 hours. In colder weather the use of warm water should be encouraged11. While soaking should be recommended, it is impossible to determine the effect it will have (short of repeating forage analysis post-soaking), so the individual horse’s response should be closely monitored.

In addition to reducing NSC content, soaking hay will also reduce the vitamin and mineral content of hay9,12, hence the need for a vitamin and mineral balancer. Soaking does not appear to reduce protein content10,12; however, when forage is fed at the levels required for weight loss, protein levels may already be insufficient7, so a balancer with a high protein content should be used.

Access to pasture is always desirable as it allows the horse to express its normal behaviour. However, when horses are at pasture it is impossible to quantify their grass intake and a tendency to underestimate overall feed intake exists. It is, therefore, advantageous to eliminate access to pasture during the initial period of weight loss in obese animals. Ponies will consume 1% of their bodyweight within three hours13 and restricting access serves to increase their hourly intake. Therefore, even short periods of turnout can severely undermine weight-loss programmes, as they may contribute all the energy required for daily maintenance with the additional hay fed – only serving to provide extra calories.

When conditions are favourable, NSC levels in grass can exceed 30% – comparable to levels in many cereal-based proprietary feeds. If pasture turnout is permitted it needs to be on to bare, well-grazed paddocks. Sand or woodchip areas of turnout would be preferred (Figure 3).

Grazing muzzles are an effective means of reducing pasture intake, although their effectiveness varies with design and between horses. Reduction in intake from 30% to 83% has been reported14-16. Grazing muzzles must be used with care and an owner guide and video is available from the National Equine Welfare Council.

Even after optimal bodyweight and condition is achieved, some animals continue to suffer from insulin dysregulation – often representatives of breeds known to be predisposed to obesity, such as Shetland and Welsh pony. In these animals, access to pasture remains a risk even when they are lean. The use of an oral sugar test is helpful in these cases to assess the insulin response and, therefore, laminitis risk, and can be repeated to assess response to management changes and pharmaceutical therapy where appropriate.

Relatively short periods of exercise (20 to 30 minutes) appear to increase insulin sensitivity, even in the absence of weight loss17. Overweight ponies that were exercised for six weeks while on a controlled diet had improved insulin sensitivity18. Half-hour sessions of exercise that raise heart rate to more than 140 beats per minute every day, or even every other day, should be advocated – assuming they will not have other detrimental effects on the animal’s health, for example, by exacerbating laminitis or lameness.

Although it may be difficult to achieve in overweight ponies, the exercise has to be reasonably intense. Unfortunately, moderate exercise, in the absence of dietary restriction or turnout to stimulate exercise, has no effect19,20. The effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity are short-lived21, so exercise needs to be regular in horses that have insulin dysregulation and it is important to maintain exercise after the desired level of weight loss has been achieved.

If turnout is to be permitted then factors that affect the sugar content of grass should be considered:

Sugar levels in hay can vary by up to 100%, according to conditions in which the grass is cut and hay is prepared. Sugar content will be minimised if:

A target of 0.5% loss of bodyweight per week is reasonable, with 1% being a maximum. This has been achieved consistently in studies of weight loss in horses7,12,22-25. During this period and beyond, if able to, owners are empowered and encouraged to monitor their horse’s progress. Figure 4 shows how this can be done with simple measurements of heart girth (4a), belly girth (4b), neck circumference (4c) and rump width (4d).

If the target weight is not reached after four to six weeks, compliance should be questioned, and the horse’s diet and management reviewed. If no compliance issues exist the amount fed should be reduced by a 0.25% of bodyweight.

Voluntary feed intake in ponies is around 2% of bodyweight, but it can be as much as 5%7, so if poor compliance with feeding recommendations or pasture turnout exist the weight-loss programme is likely to fail. Even with identical management, marked variation will be seen in rates of weight loss between individuals and some horses will exhibit marked weight-loss resistance22. A reduction in the amount fed to less than 1% of bodyweight is not recommended, as dramatic feed restrictions may be associated with stereotypic behaviour, gastric ulceration and hyperlipaemia.

Up to 50% of the hay ration can be replaced by straw to further reduce calorie intake while maintaining fibre intake; however, straw feeding has been identified as a risk factor for equine gastric ulcer syndrome. If weight loss is not achieved – having reduced feed to 1% of bodyweight of low sugar forage – pharmaceutical treatment should be considered (discussed in part two).

In the management of type-2 diabetes in adults, the degree of weight loss correlates with the number of contacts with the health care provider26. It has also been suggested follow-up contacts are as important in further educating the patient and re-enforcing the importance of managing obesity, as they are in assessing progress and modifying the diet and management plan5. Regular reassessments should, therefore, be scheduled from the outset or they possibly will not happen.

Once the target weight is achieved, it is important monitoring is continued as experience from other species indicates diet and management changes will not be maintained in a large proportion of cases, and many will return to an obese state.

Horses that have lost weight may still exhibit insulin dysregulation and, while this can be evaluated, if the patient has a history of laminitis it is prudent to continue to provide low sugar feeds that limit hyperinsulinaemia. A high-fibre/low cereal diet is a more natural and healthier way of feeding any horse, so a return to feeding cereals after weight loss should be discouraged. Any subsequent gain in weight, however transient, is likely to be associated with decreased insulin sensitivity and, therefore, increased laminitis risk.

Recommendations similar to those outlined previously have been demonstrated to be effective in a study of client-owned animals in the UK25. Of the 19 horses and ponies studied, 18 showed a reduction in body mass, and all had a reduction in body condition score. Mean weight loss after 161.6 days ± 147.5 days was 43kg ± 39.3kg, which corresponded to 8.9% ± 6.7% of bodyweight. Furthermore, reductions were seen in basal insulin levels and insulin and glucose responses, which would suggest a reduction in the risk of laminitis.

Compliance in this study was very high and owners of the horses studied may have been more motivated than most; however, the results provide reassurance that if recommendations are implemented, weight is lost. If it does not, it is likely measures are not being followed.

In a more controlled environment, greater improvements in bodyweight and insulin sensitivity have been reported.

McGowan et al (2012) documented a mean of 6.8% reduction in bodyweight in 12 overweight client-owned horses fed and managed by the researchers12. Weight was lost in all horses with a range of 3.5% to 9.9% over the six-week period and an average of 1% of bodyweight lost per week. Insulin sensitivity increased only after six weeks; there was resolution of active laminitis and absence of recurrent laminitis in all six horses that had laminitis initially within the trial period.

A number of other groups have reported consistent and significant weight loss of around 1% bodyweight per week, accompanied by increased insulin sensitivity, with dietary restriction alongside exercise and nutraceutical supplements in some studies7,22-24.

Measures that need to be implemented to induce weight loss are simple. While individual variation will be seen in the amount of weight lost, the evidence from horses kept in controlled conditions indicates, if measures are implemented, they will be effective. However, in practice, weight-loss programmes frequently fail because of poor compliance and this, along with potential pharmaceutical interventions, is discussed in part two.